Review: Wolf

Shannon Friday reviews Christchurch playwright Tim Barcode's thirteenth play, Wolf, a seamy melodrama set in the aftermath of the 2010 quake.

Shannon Friday reviews Christchurch playwright Tim Barcode's thirteenth play, Wolf, a seamy melodrama set in the aftermath of the 2010 quake.

After seeing Wolf, my brain hurts. I feel angry.

This isn’t because I’ve just seen some mind-blowingly intense drama. It's not because I’m outraged at the administrative cock-ups that followed the Christchurch earthquakes, or because I’m afraid of what will happen when Wellington finally gets its big shake. It's not because I’m having any sort of response that anyone who made Wolf wanted me to have.

It’s because Wolf uses the Christchurch earthquakes without thought and without care. It’s because, to Wolf, the quakes are nothing more than a convenient dramatic device.

Wolf is set after the September 2010 quake, “the big one” before the actual big one in February 2011. As it opens, Ali’s (Pip O’Connell) greeting potential flatmate Mike (Ryan Mead). He’s a recent hire at EQC whose last flat was damaged in the September quake; she needs help with the mortgage. Then next door neighbour Cassie (Susannah Donovan) and Lee and Cushla (Hugh Parsons and Talia Carlisle), the young couple living in a sleepout, make themselves known. Then an aftershock hits.

That first aftershock firmly establishes each character through their reactions: Ali grabs her wine glass to keep it from tipping, Lee freezes, Mike bolts to the door, and Cushla rocks back and forth under the table, chanting that she feels safe. It’s a great demonstration of the different psychological impacts of an earthquake, a scene designed to shake us out of our complacency around earthquakes. It’s a sample of what Wolf could be.

So it’s weird that, after this point, Wolf barely addresses the earthquakes or their impact. The story is basically a retread of those old melodramas where everyone is trapped in a remote mansion and harbouring dark secrets they’re trying to keep from everyone. Ali’s daughter Mel is also Lee’s ex-girlfriend, but the circumstances surrounding Mel’s death are shaky… as shaky as the ground under the characters’ feet. Nosy neighbour Cassie is concerned that Ali and Lee’s closeness is turning sexual, but Cushla is more worried about Lee’s alternating insomnia and nightmares than she is about ancient history. Everyone’s giving Mike crap about his job, and he’s defensive about it, but he’s also attracted to Cushla, and Ali’s… irritated by this.

Wolf’s that kind of melodrama, and it tries to match its melodramatic story with grotesque characters in a hyper-realistic world: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo but for the Christchurch earthquakes. But there’s nothing grotesque in the characters, no clear world, and no rising action to back up the ham-fisted stabs at thematic depth. Wolf is consistently undermined by this lack of strong vision from writer Tim Barcode and director Sam Fisher. Their characters are flat on the page: they’re the "alcoholic", the "steampunk", the "youth." We’re told about their relationships through exposition, rather than shown them through dialogue and action. Everyone talks to everyone else the same way about everything, miles away from the varied reactions to the first aftershock. All of this is deadly in a show revolving around secrecy and sexual intrigue.

With no subtext, no relationships and no clear conflicts to latch on to, the actors are left with little to work with. So they flail around for something solid, reaching for emotion the moment they find an opportunity. As a result, they often blow their tops way too early, obscuring any emotional contrast in a scene. When the characters play the party game Werewolf, for example, trying to work out who’s the werewolf killing the villagers, the actors lean hard into their first moves: Lee viciously teases Mike and he unleashes a volcano of anger in response. It’s a scene that’s trying to tease out all the undercurrents of resentment between the cast, and it requires a light touch so all the alliances can play out. But the extreme violence of that first exchange diminishes the impact of any further changes in alliance.

The earthquakes and aftershocks almost always occur when there’s a break in the action, a change of subject or a transition. They’re helpful, reducing those traumatic events to a dramatic convenience.

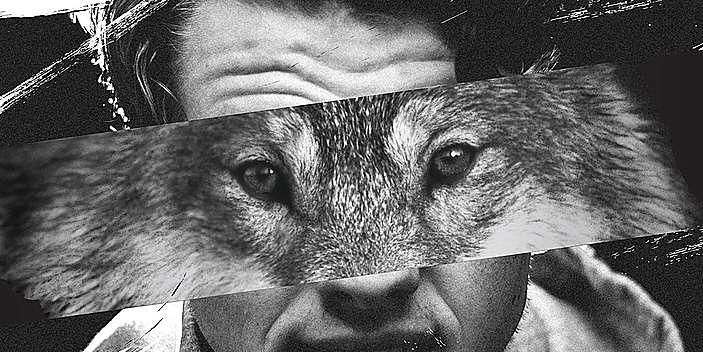

Wolf underlines this domestic drama with images of feral wolves that are meant to stand for everything reverting to nature, but the lack of detail means we never see people descending into wildness or decay. Everyone starts out a hot-tempered jerk and finishes the play a hot-tempered jerk. Further, characters are constantly talking about how people aren‘t what they seem. After all, “wolves” freely roam the streets, especially the lone predators in high-vis EQC vests and the feral packs vandalising abandoned houses. Boom. That’s the metaphor.

That clumsy lack of detail extends to the design. I can’t help but compare Wolf to The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo again. Dragon Tattoo constantly drops details about characters through their living spaces: dirty dishes (careless), slick espresso machines (urbane), finicky wood burning heaters (old-fashioned to a fault).

In contrast, Wolf’s lounge setting is stereotypical BATS realism-on-a-budget. Where Dragon Tattoo’s choices constantly reinforce the message that people shape their world and are responsible for their actions, Wolf’s set is functional and little else, all it reveals is how hard it is to find five matching living room chairs when touring a show to Wellington. Moreover, the stock table, chairs, and sofa are placed solely to give the audience the best view of the acting while people are sitting on them, limiting any opportunities for exciting stage pictures and acting challenges. There are so many opportunities in Wolf to use the set to show how humans and nature fight over who gets to shape their world, but the show places us squarely in the theatre, squandering any chance of showing that conflict.

When Wolf does start talking about natural forces, it’s clumsy to the point of being insulting. The earthquakes and aftershocks almost always occur when there’s a break in the action, a change of subject or a transition. They’re helpful, reducing those traumatic events to a dramatic convenience.

Moreover, characters tell us again and again that the quake has impacted services and that the Council and EQC are “useless bastards”, but we never see any of it because of Wolf’s myopic focus on who’s sleeping with whom and who’s hiding what ridiculous secret. Take Mike: even though he’s an EQC employee signed up in the initial post-Quake panic, his job never has a meaningful impact on the drama. Mike is defensive about his job from the outset, and Barcode’s script pushes us to see his shame as correct when the other characters snub and exclude Mike because of his job. We’re encouraged to join in celebrating Mike’s public shaming because he works for the evil insurance company. But, as audience members, we’re never given a specific reason to dislike EQC; perhaps Barcode assumes I already have plenty. Instead of digging into the dramatic possibilities of Mike’s career and how it affects his ability to function in every other area of his life, Wolf turns Mike into a bad guy the moment we find out who he works for, abusing him as a proxy for the EQC at large. It reads as a complete lack of empathy for anyone associated with EQC, and I’m grossed out by how this panders to our ugliest anti-establishment impulses.

Most importantly, though, nothing in Wolf involves its characters trying to deal with living in a city that’s been badly shaken. There’s no specificity to Wolf: even its set-up, with the characters all moving into a house because of the damage to their old homes, could swap in any other reason for the move and events would play out the same. The plot's final turn doesn't even involve the quakes at all. Instead, it’s an implausible, out-of-left-field reveal revolving around an event that took place months or years before either quake.

You could transport Wolf to any place and any time in the last 70 years, and nothing would change. That's the problem.

Wolf runs at

BATS Theatre

from Tuesday 15 - Thursday 24 March

For tickets and more information, go here.

A previous version of this review incorrectly refered to the major 2010 Christchurch earthquake as occuring in November.