The Lyrical and the Literal: A Review of When Sun and Moon Collide

Kate Prior rediscovers the poetry of 'When Sun and Moon Collide', but finds it stymied by the production’s soapy literalness.

Auckland Theatre Company has opened a rare remount of Briar Grace-Smith’s When Sun And Moon Collide. Kate Prior rediscovers its poetry, but finds it stymied by the production’s soapy literalness.

Dan Williams’ silk flats look like the reflective surface of the moon. Layers of them hang from the rig and push in behind the triangular frame of his dusty, unreflective, avocado-coloured tearooms. Like Briar Grace-Smith’s writing, his design offsets the suggestive and poetic with detailed naturalistic banality: the windows are broken and scummy, the specials on the blackboard have been chalked up in a rush, there’s a strange old jukebox in the corner for no one to play and there’s a distinct feeling we could be at the edge of the world. I kind of want the well-matched formica tables and chairs to be a bit more shit, but the weird matchy-matchy quality adds to the feeling of misplaced kitsch; inherited, dated emptiness.

Playwright Briar Grace-Smith was incredibly prolific from around 1995 to 2000 – sending five plays into the world which are now landmark New Zealand works, such as Nga Pou Wahine, Purapurawhetu, Haruru Mai and of course, When Sun and Moon Collide. Her work has been described as magic realism, but I've often wondered if that’s just an easily-digested Pākehā phrase delineating two worlds that in Te Ao Māori are inherently connected.

It’s rare for any of these works to be restaged by mainstage theatres (most play revivals skewing older and, well, male). But seventeen years after When Sun and Moon Collide premiered at BATS, it’s now playing in full Auckland Theatre Company-budget glory. And how bloody wonderful it is to see a mainstage revival of a recent New Zealand classic – to feel the time between then and now and to see how it stands in a theatre in 2017. After all, stories are made richer each time they’re repeated.

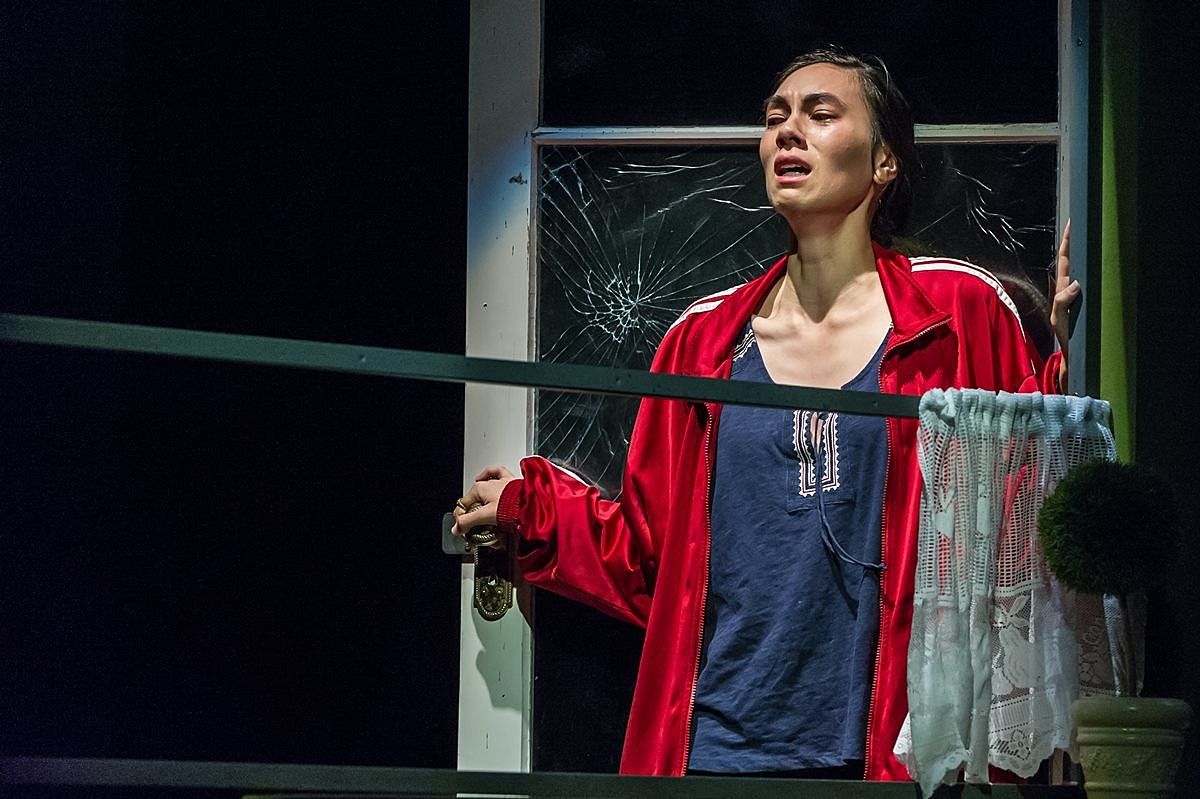

When Sun and Moon Collide explores family disconnection, loss and the inheritance of trauma. The narrative is structured around the lunar cycle, beginning and (almost) ending with mutuwhenua (the phase of the cycle when all is dark). Each of the four characters are labouring in darkness – isolated or trapped in some way: Declan (a rangy Joe Dekkers-Reihana) by his rage and the legacy of being abandoned; teenage Francie (a skittish Emily Campbell) by the psychological wounds of her abuse which manifest as an eating disorder; Isaac (an earnest Jack Buchanan) by his reliance on bland tradition (keeping the archaic tearooms alive); and Travis, the town cop (a winking Kura Forrester) by her dependence on her relationship to Vic – someone who’s not as he seems. The blindness of mutuwhenua suffocates each of the characters until they finally wake to it and break free.

The action of the play pivots on the mystery disappearance of two Danish tourists near the small Horowhenua town, and at face value, it can be read as a kind of whodunnit, but there’s an allegorical nuance to the story which is where its lingering echoes lie. Like Chekhov, the small-town tearooms are Grace-Smith’s Cherry Orchard; a symbol of a New Zealand which is no longer, a problematised space which hinders as much as it shelters. As Alice Te Punga Somerville writes “As for Isaac, if he is Pākehā, are we compelled to think of the play as an allegory for colonialism? Do the tearooms he inherits from his mother (England? Early settlers?) act as an emptied/obsolete/no-longer-nurturing national space?”

The small-town tearooms are Grace-Smith’s Cherry Orchard; a symbol of a New Zealand which is no longer.

In director Rawiri Paratene’s production, we’re blindfolded to this lasting symbolism. Dan Williams’ design poetry aside, there’s a pervading sense of flat, Shortland Street literalness to this production which manifests in overly-weighted melodrama and misplaced comedy (a caricature laugh here and a very soapy “because I love you” moment there). Perhaps there’s a misconception that these ‘larger’ moments could amount to a more dramatically satisfying work, but in their bigness, they diminish the potential for poetic breathing space. Lyricism blossoms when it’s not laboured, and once you start flat-footing around by pointedly signalling gags and leaning towards schmaltz, you burst the balloon of our symbolic synapses and all we’re able to read is the heavily-plotted literalness of narrative.

It has me thinking: perhaps allegory requires an even deeper commitment to understated realism and specificity – actors playing the action, not the audience. In this production, there’s no clear directorial vision when it comes to performance; there are moments when an actor alone onstage speaks a poetic monologue fuzzily out to the ether (it’s not clear why they’re telling this story or who they’re speaking to), many times when actors walk downstage for no great reason, looking outwards feverishly, and occasions when actors send up the lyricism of the text. But in order to mine the finely-calibrated balance of levity and darkness that Grace-Smith offers, it requires from a director a clear-eyed, understated approach towards the realism: actors working with distinct detail, playable action and clear intention.

In the author’s preface in the published play script, Grace-Smith writes of her inspiration for the play, which came “during a time when I was commuting four days a week from my home in Paekākāriki to Massey University in Palmerston North. For three hours a day, I was passenger in a car, and it gave me plenty of time to gaze out of the windows. I soon began to scan the landscape for a couple of familiar sights: an abandoned tearooms and a very slim girl who, every morning, ran through the paddocks as if she were being chased, but there was never anyone else around.”

There’s such a tingling mystery in that image that no matter how many times I read it, I get goosebumps. The production picks up the image and has Francie pounding up and down behind the silk flats – a running figure in shadow, trapped in a rhythm. It gave me goosebumps again. Briar Grace-Smith’s When Sun and Moon Collide is haunting in the way it taps into the inherent strangeness of totems to bygone eras, and the hidden heartbreaks of empty towns. But in this production, those goosebumps don’t stick around.

When Sun and Moon Collide runs from 20 June – 6 July at ASB Waterfront Theatre. Tickets available here.