Clouds And Rain Over Water: A Review of Under

Adam Goodall reviews Under, a "modern day memory play" that involves the audience in one character's act of remembering and takes us on an affecting, if familiar, journey.

Adam Goodall reviews Under, a "modern day memory play" that involves the audience in one character's act of remembering and takes us on an affecting, if familiar, journey.

NOTE: This review contains major spoilers for Under.

Every twelve months or so, a passage from a letter that Raymond Chandler wrote back in 1945 makes the rounds on Twitter. In that passage, Chandler argues that regardless of what editors have tried to tell him, the reader doesn’t care about action. Not really. What the reader really cares about, in Chandler’s view, is the creation of emotion through dialogue and description. The reader remembers how the moment felt, the weight and sensation of it. They don’t care about the event of someone dying; they care about how “in the moment of death he was trying to pick a paper clip up off the polished surface of a desk, and it kept slipping away from him, so that there was a look of strain on his face and his mouth was half-opened in a kind of tormented grin, and the last thing in the world he thought about was death. He didn't even hear death knock on the door. That damn little paper clip kept slipping away from his fingers and he just wouldn't push it to the edge of the desk and catch it as it fell."

Under, the new play by Cassandra Tse (most recently one of the writers behind the ‘MRA musical’ M’Lady), takes that lesson to heart. A man’s wife has disappeared. He asks us for help finding her; our job is to listen to his memories of their relationship and respond. He doesn’t tell us many stories, but that’s not the point. He’s an editor by trade and one of the rules of his work is that half of storytelling is what you don’t say.

The point is the detail – the look and feel of a piece of furniture, the movement of a woman swimming, the sensation of falling in love. He lingers on the texture of those memories, the quality of their happiness or sadness or pain. The texture is the key to him remembering these things in the first place. He has trouble recalling objective facts. He needs post-it notes for those.

The man takes us on an intimate journey through those memories, from the late 1960s – when he met May, the swimmer and painter with whom he fell giddily in love – through to the present day. He has an uncomplicated sense of humour: at one point, he goes on a surprisingly charming bend about how often he loses track of his glasses, a story that you’ve almost definitely heard someone’s grandparent tell at some point in your own life. That’s pretty characteristic of the small stories he tells. His stories focus on the small, weird moments in his relationship, and he tells us about those moments with the kind of fondness and attention to detail that you only get from people who are talking about the people they love.

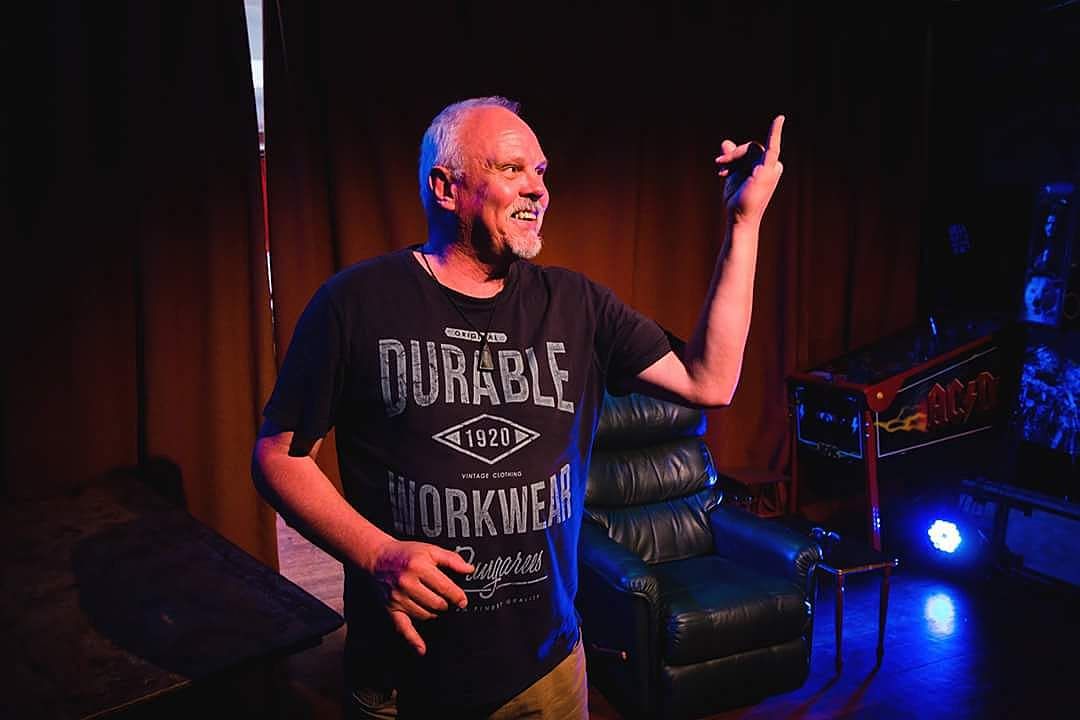

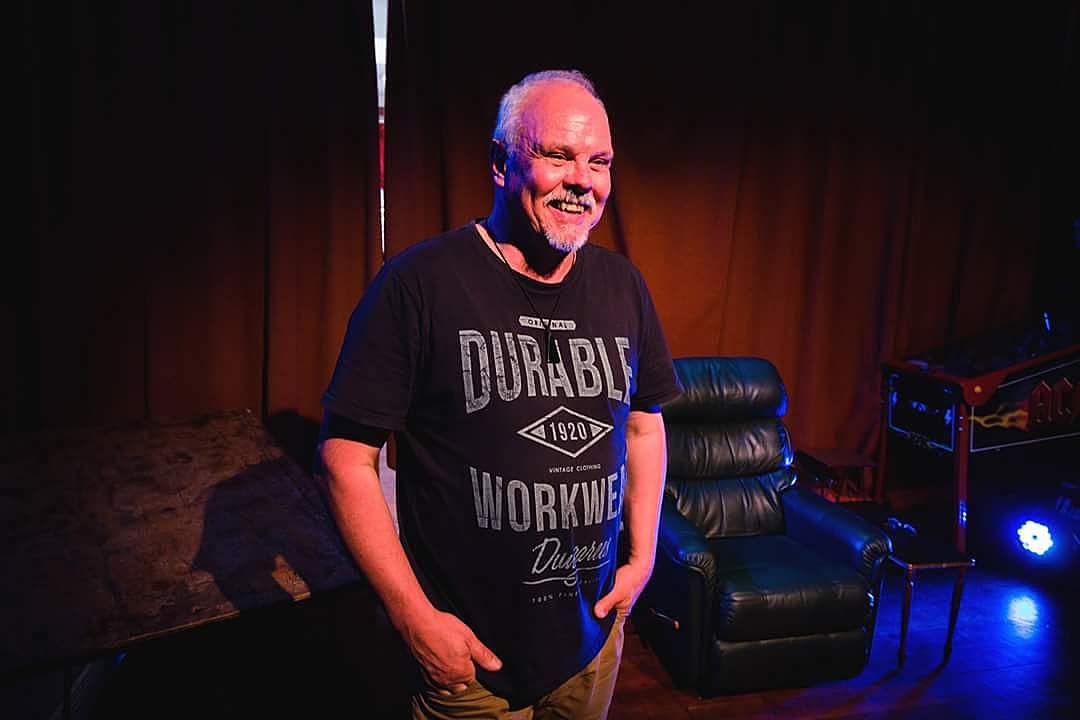

Chris Green plays the man. He’s got an unpretentious look, with close-cropped grey hair, a dark t-shirt and khakis; his voice is deep and slightly strained, like it has some history to it, and it gives his monologue texture. Director James Cain leaves his performance largely unvarnished – there are few flourishes in the blocking and the set, a lazyboy and a Warehouse bookshelf with some old books, is appropriately utilitarian. But when Green is at his most nostalgic, recalling beautiful, deeply-cherished parts of his and May’s life, Cain builds on the romance: the space sinks into blue and Will Evans’ dreamy synth compositions drift underneath.

If memory is a two-player game, though, as the man tells us at one point, he’s spent a lot of time training. His memories feel written and rehearsed, the alliteration and sibilance practised. Green leans on the poetry like he’s trying to force us to acknowledge it, emphasising how water is as sslick as dishssoap when you walk on it. It feels off, a bit over-emphatic and over-designed, but there is a purpose to it.

That purpose is alluded to early and often. As in her last drama, Long Ago Long Ago, Tse’s lead’s interest and career in literature is integral to the way she tells his story. Early on, the man has a laugh with us all at the expense of the writers who, rushed or lazy or both, send in manuscripts halfway between the first and second draft, filled with loose strands and tired adjectives. He tells us that, as a freelancer, he edits a lot of erotica, and he’s read about enough abs “rippling” and bosoms “heaving” to last ten lifetimes.

The man's stories focus on the small, weird moments in his relationship, and he tells us about those moments with the kind of fondness and attention to detail that you only get from people who are talking about the people they love.

His story is meant to be the opposite of this. His scenes are specific, focussed, playing with words in a way that a regular person wouldn’t if they were just recalling memories off the top of their head. Green’s man talks about how May always loved JMW Turner, who painted his sunsets in striking pigments that faded over time, but he rejects that. He wants to paint a landscape rich in detail and life, a picture that’s vivid and stays vivid. This feels like a performance, and you never really forget it.

It’s extremely hard to explain this further without spoiling the show because so much of its impact pivots on a reveal that, reading this, you may already be suspecting. But there’s a reason it feels like a performance – it is a performance. May has Alzheimer’s, has had it for a while, and the man has been telling her this story for some time, over and over, trying Notebook-style to ‘bring her back’. Under casts us as May, distant and unfamiliar as the man asks us if we’ve felt “a sense of her”, if we can un-disappear her.

This changes things, obviously, reframing the story and giving it a tough, bittersweet coda. After all, if we ‘are’ May, we can never truly know the man: just hear his story, respond, then leave, to be replaced by another sea of unfamiliar faces. It’s an interesting twist on this kind of monologue and it leaves us with the feeling of an inescapable, pervasive melancholy. But it also falls into its own traps.

Like the erotica the man edits, Tse’s descriptions of how people experience Alzheimer’s – both the person suffering from the condition and the people closest to them – feel limited in their expression. The man’s words sometimes fail him and he turns to familiar verbs and images to express the depth of his pain (at one point calling May a “discarded husk”). But the structure and the rhythm of the monologue inexplicably holds strong, indistinguishable from the rest of the show despite the man’s growing anguish.

Green feels like he’s pushing his performance hard, too. But that pushing doesn’t always come across as a man trying to break through the fog of Alzheimer’s, a man trying to maintain his composure in the face of loss. That’s clearest in the moments when he addresses us directly. He asks us if we can “sense” her, but he doesn’t seem interested in our responses; he asks us to lift our eyebrows or smile like she used to, but he doesn’t wait for us to do it, instead moving quickly on to the next request. He looks past us, at some figure into the middle distance, as much as he looks at us and sees us as May. He doesn’t work with us, and that detachment from us as an audience makes it harder to accept the third-act reveal that he’s trying to connect with us as May. He just moves too fast for that.

Still, there are strong and melancholy moments in Under. It’s a solid and sensitive drama, if very familiar, right down to story beats that echo some classic tropes of Alzheimer’s narratives, and of New Zealand theatre more generally. But when it stops and takes its time colouring in the scenes, shading and lining and trying out bold pigments, it’s vivid and rich and – as some people in the opening night audience could tell you – perfectly designed to hit you right in the gut.

Under runs from 2 to 11 November at The Third Eye, 30 Arthur Street, Wellington.

Tickets available here.