The (re)Construction of Cultural Memory: A Review of Two Oceans at Once

Who was the first person to see the Pacific Ocean? Talei Siʻilata on how Two Oceans at Once debunks the myths of colonial narrative.

Who was the first person to see the Pacific Ocean? Talei Siʻilata on how Two Oceans at Once debunks the myths of colonial narrative.

Two Oceans at Once draws its name from Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano’s retelling of the common known history of the world. The phrase itself is taken from a passage in which Galeano describes what is believed to be the first European sighting (and naming) of the Pacific Ocean in 1513, by Spanish explorer and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa, after he ascended the summit of the mountain range along the Chucunaque River in Panama. The story of Balboa’s sighting or ‘discovery’ and the contention it creates in Galeano’s retelling because of what it omits (namely pre-existing indigenous voices and stories), is what provides the impetus for Two Oceans at Once to question similar historical accounts prevalent in Aotearoa and the wider Pacific region; their framing and what they too have chosen to omit.

Each artist is at times an unlikely intervener within the interstices of cultural memory, both deconstructing and reconstructing it anew.

This premise paves the way for a grouping of very different works within the exhibition that, in the words of curators Cameron Ah Loo-Matamua and Charlotte Huddleston, “live in this [in-between or] interstitial space, accommodating many points of departure (and arrival) while looking to create a vision of the future”. Each artist is at times an unlikely intervener within the interstices of cultural memory, both deconstructing and reconstructing it anew. Within this framing, Two Oceans at Once situates the retelling and repositioning of history as an important practice to make visible the lived experiences of people and communities that have been disregarded due to the privileging of a singular historical narrative.

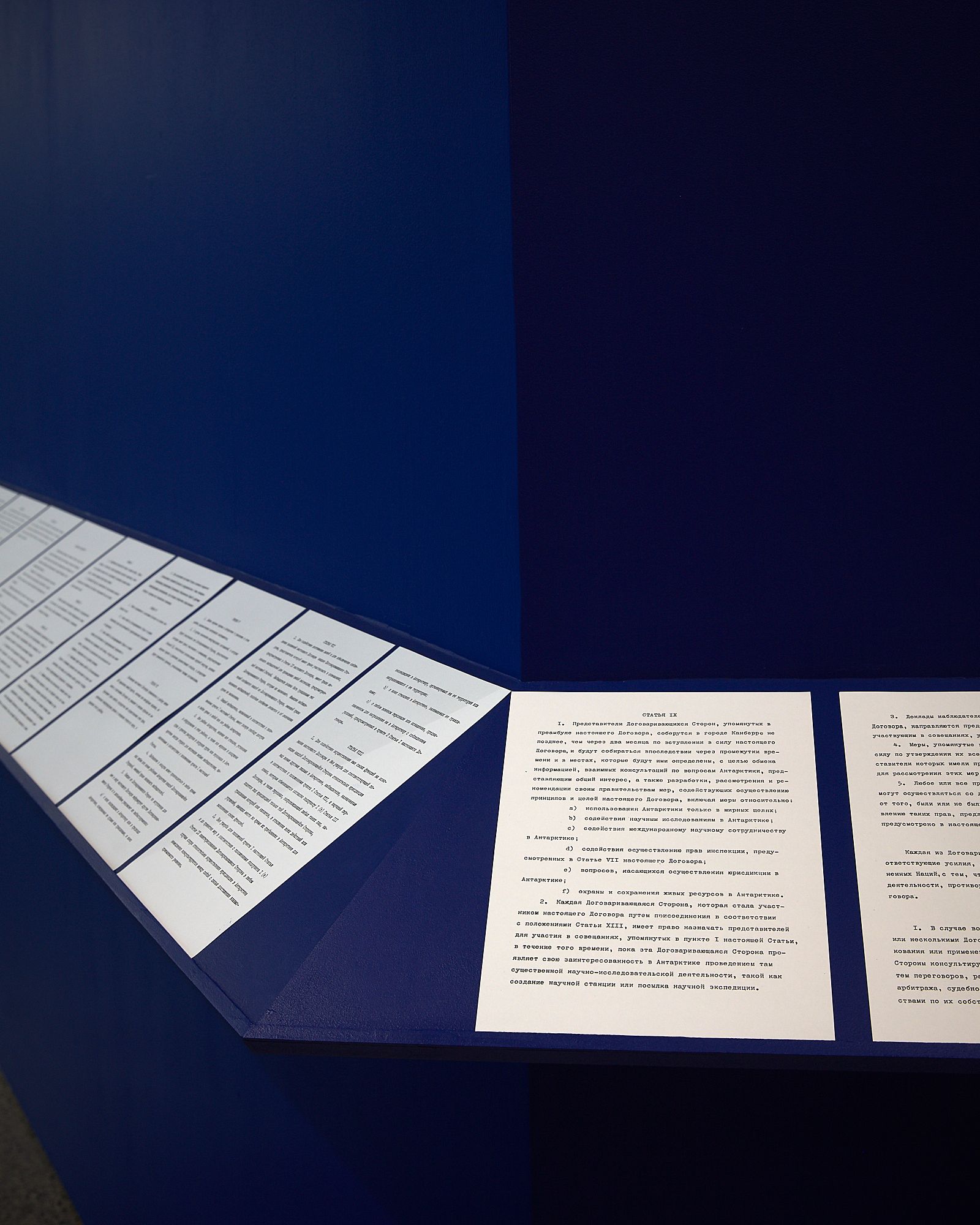

Jane Chang Mi’s Te Tiriti o Atātika (2015), for example, is one such intervention. The artist, who trained as an ocean engineer at the University of Hawai‘i, had the Antarctic Treaty of 1959 translated first into Ōlelo Hawaiʻi, and then into Te Reo Māori. The treaty was signed by the governments of Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, the French Republic, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, and the United States, but the text was produced only in English, French, Russian and Spanish. The treaty is important precisely because it does not recognise any sovereign nation's claim on any part of the Antarctic territory.

The translation and printing of the treaty in Ōlelo Hawaiʻi and Te Reo Maori by communities who collaborated with Mi is a clear act of assertion that makes visible those communities that the treaty neglected, and makes viable their claim to be heard. This is especially important given that increasing global temperatures, which continue to melt Antarctica’s glaciers, are drastically raising sea levels that devastate first and most significantly nations of the Pacific Ocean. As someone who works at what essentially is ‘ground zero’, Mi’s interest in the collective heritage of the Pacific is a direct result of her maritime research and her growing interest in “what constitutes the natural world and what lies in the realm of history”.

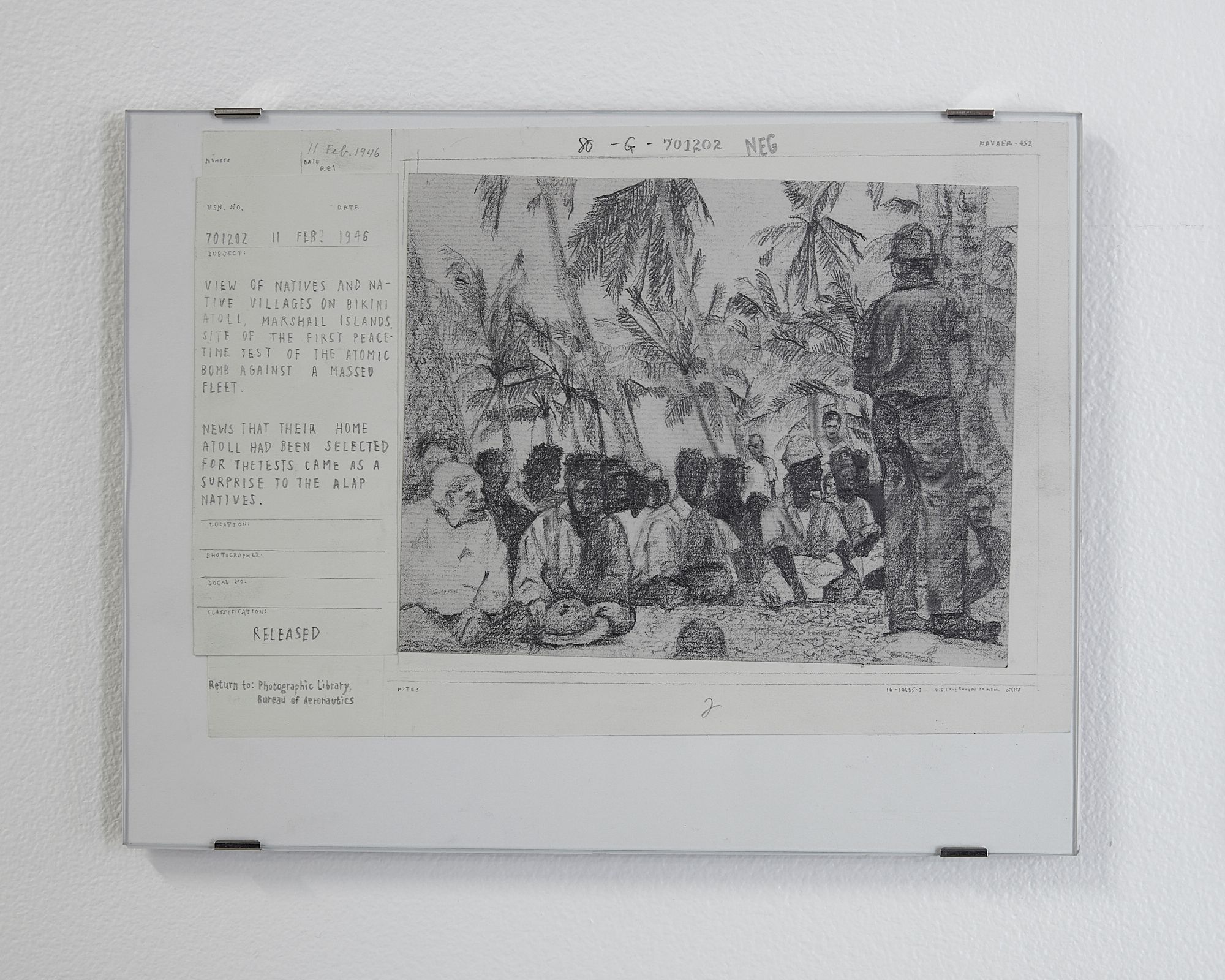

Mi continues this train of interrogation in her 2017 multipart work (See Reverse Side.), which deals with the physical, environmental and cultural trauma experienced by Marshall Islanders during their removal from the atolls of Enewetak, Bikini and Johnston due to nuclear testing carried out by the United States. Mi emphasizes the great care given to photographically documenting this process of nuclear testing and evacuation alongside the simultaneous and stark lack of care of the very people this process would affect for years to come. Her access and research into government archives detailing these tests and her subsequent reproduction of some of the images in sketch form, a painstakingly careful method of preserving and humanising these memories, is a remedial exercise.

In addition to righting what can be seen as historical wrongs, the works in Two Oceans at Once often illustrate the constant negotiation that is at play in colonial sites between “two histories, two outcomes, two sets of beliefs, two stories”. And this is precisely what is evoked in Yonel Watene’s (Ngāti Maru, Hauraki) sculptural works Zug Island and Fighting Island (2015–18), named for real-life islands in the Detroit River. In Watene’s words, Zug Island, an American territory, signifies “relentless colonisation, which leads to a ruthless representation of capitalism and industry (with absolutely no remorse)”, while Fighting Island, a Canadian territory, represents “Pre-Industrial colonisation, that leads to ecological deterioration, and then remorse, which inspires the colonisers to decolonise the area, leading to rehabilitation”. These two histories result in two starkly different realities and islands, demonstrating what Watene calls, “the battle of our time (colonial v decolonial, capitalism v nature and everything, life v death)”. Although not a native of Detroit, Watene saw within the histories and realities of these two islands, two distinct and opposing responses seen universally in the post-colonial age, “…that one colonial power took action and one didn’t”. In Watene’s mind, all colonial experiences can align themselves with either of those two responses, making the stories of Zug Island and Fighting Island universal narratives. In his own words, “The results are evident and applicable because invasion is invasion, in the Pacific, North Pole or Kathmandu.”

The desire to reify, to make tangible, what are often hidden or transient spaces and experiences is a theme that is also revisited throughout the exhibition

The desire to reify, to make tangible, what are often hidden or transient spaces and experiences is a theme that is also revisited throughout the exhibition. Rozana Lee’s Adzan (2018) uses tsunami-soiled fabric as a backdrop for the projection of a single-channel, looped video work displaying a small harbour located in the Sumatran province of Aceh, Indonesia, which was devastated by the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, and was also where Lee was born. The landscape and soundscape of the work are composed of naturally occurring phenomena that are both temporal and time-constricted. The sound of the waves, of people’s conversations in the background, the echoing of the Islamic call to prayer being methodically recited over speakers, all embody the intersecting notions of national identity and experiential belonging that occur in Indonesia. As a fourth-generation Chinese migrant who grew up in Aceh, Lee’s practice aptly questions, “How many generations make a complete belonging to a place?” This question, along with the nostalgic yearning that Adzan evokes, is made more poignant by the fact that Lee was forced to flee Indonesia in 1998, following anti-Chinese minority violence in the form of robbery, rape and murder.

The notion of historical record versus cultural memory or collective memory is a point of contention in many of the works featured in Two Oceans at Once, operating as they do in the space ‘in-between’ these two rubrics. Watene’s series of Untitled Margo Glantz Paintings (2018–19), which are composed of silkscreen prints of the Mexican writer Margo Glantz (who Watene came across a poster of while in Oaxaca city) on treated denim, also features an excerpt of Glantz’s writing (translated to English here) repetitively stamped in a small, at times illegible font that reads,

They say that memory is self-reinforcing and perhaps this also applies to forgetfulness.

If, as Glantz claims, both memory and forgetfulness are self-reinforcing, it is historical memory – seen as chronological and linear – that is self-reinforcing. This is the same as a practiced forgetfulness; the selective and practiced forgetfulness of any pre- or co-existing narratives that might support an alternative cultural memory. And it is this crucial systematic myth making that Two Oceans at Once seeks to debunk.

In foregrounding other stories, both their own, and other communities’, the artists in Two Oceans at Once broaden our understandings of the past and present, to include accounts that run parallel to and across those fixed linear narratives of history.

When retelling the story of Balboa, Galeano wrote, “Official history has it that Vasco Núñez de Balboa was the first man to see, from a summit in Panama, two oceans at once. Were the natives blind? ... Were the natives mute? … Were the natives deaf?” In essence, these are the very same questions Two Oceans at Once confronts viewers with, and attempts to answer with a resounding ‘NO’. Each artist who is featured in the exhibition is, in some way or form, stretching the boundaries of what constitutes historical memory, both on a personal level, and in a larger macrocosmic sense. In foregrounding other stories, both their own, and other communities’, the artists in Two Oceans at Once broaden our understandings of the past and present, to include accounts that run parallel to and across those fixed linear narratives of history.

In the words of curators Ah Loo-Matamua and Huddleston, “Recognising that there is no singular past, present, or future … Two Oceans at Once is a quiet gesture toward the many worlds we hold as individuals and citizens of a global community.” It is a celebration of the multiplicity that forms collective memory.

Feature image, top of page:

Foreground: Yonel Watene, Zug Island and Fighting Island, 2015–18, permanent sculpture, third and final installment in the Detroit series.

Background: Ruth Ige, Parallel worlds and the mundane, 2019.

Photo: Sam Hartnett

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the ST PAUL St Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.