Tricky Dick: A Review of 'Something to Behold!'

Lachlan Taylor on the unending colonialism of Dick Frizzell.

Lachlan Taylor on the unending colonialism of Dick Frizzell.

I don’t like Dick Frizzell. It’s hardly a controversial statement, and I am definitely not alone in saying it. Yet despite every impulse telling me that in 2017, the time for giving a shit about Dick Frizzell has long gone, it is a statement I find myself returning to again and again.

But Dick doesn’t care whether I like him or not. He has built a career out of provocation, standing fast against waves of public opprobrium. And they have always been waves of his own making. He has let criticism and critique wash over him and his motley array of appropriative paintings, and it has worked for him. In a certain sense, Dick Frizzell, the Art Darling with a face like the lovechild of Sam Hunt and Robert E. Lee, remains a fixture of contemporary New Zealand art. His career has waxed and waned over four decades, but Frizzell’s head has never sunk too far below the water.

Dick has been waiting for a review like this. The provocation and reaction, the expectation of controversy, is an essential part of the experience for him, maybe even the essential part.

Just when he had exhausted his practice as a painter of the landscape in the 1980s, Frizzell invigorated his reputation with Tiki at the Gow Langsford Gallery in 1992. Tiki was an exhibition which employed the recognisable and precious taonga of the tiki to stage a premeditated attack on Māori people and culture. He took the carved figure of the tiki and rendered it in a variety of Western painting styles, from cubism to pop, deliberately engaging with the tradition of ‘primitivism’ with Frizzell self-cast as ‘arch-villain’. The exhibition positioned Frizzell as a hip, avant-garde player, offering a salve to liberal Pākehā whose patience was being tested by a climate of political correctness and cultural safety. Now, after two decades of building a commercial oasis in a critical desert, Dick has forced his way into our artistic conscience once more. In recent weeks we have seen the opening of Something to Behold!, his solo exhibition at Wellington’s Page Blackie gallery, as well as the upcoming Art Ache event at Golden Dawn in Auckland, From Tiki to Tiki, which will celebrate the “25th anniversary of taking the tiki mainstream” (I know).

Dick has been waiting for a review like this. The provocation and reaction, the expectation of controversy, is an essential part of the experience for him, maybe even the essential part. Knowing that, I was hesitant to write this – better to starve the oxygen than feed the flames – yet here I am. These are important events to talk about. Not just as yet another criticism of a perennially problematic artist, but as an opportunity to take stock of the wider culture that the cult of Frizzell has come to represent. I get the appeal in his work, I really do. And I want to express that as fairly as possible. At this point, I need to acknowledge that I am writing from the position of a cis-male Pākehā, and so I am attached to all of the biases and prejudices that come with that identity. This makes it problematic to write about Dick Frizzell. I am his audience, his identity. But it is time to think about what is at stake in the continued promotion of this kind of practice. It is time to talk about the many masks of Tricky Dick.

Frizzell’s masks are many and varied. Something to Behold! is an engaging show, and it says a number of interesting things about Frizzell and the economies – both artistic and more broadly commercial – that support him. From Tiki to Tiki is an intervention in these economies from a new generation, whose theoretical landscape is pockmarked with old (and unresolved) controversies that hold currency but increasingly appear irrational and intolerable. Art Darling is a mask that Dick likes to wear, but it is not his only one. In recent years, it has become increasingly difficult to avoid Dick Frizzell: Kitsch Kapitalist. In 2009, one of his many iterations of the ‘Four Square man’ adorned the cover of The Great New Zealand Songbook. In the same year, he also released limited-edition bottles of merlot and pinot gris under the moniker ‘Frizzell Wines’, and painted a mural in conjunction with his son, Otis, which was installed at Moore Wilson’s, Wellington’s bourgeois supermarket supreme. In 2016, Countdown began selling reusable shopping bags emblazoned with From Mickey to Tiki tu Meke prints. That same year, he partnered with glasses manufacturer Specsavers to produce a line of Frizzell-designed spectacles. The painter’s decades-long engagement with the kitsch of kiwiana has come full circle to the point where his designs constitute a kind of kiwiana in themselves – a fact that I am sure Frizzell delights in, and which has borne lucrative commercial fruit.

From Tiki to Tiki is an intervention in these economies from a new generation, whose theoretical landscape is pockmarked with old (and unresolved) controversies that hold currency but increasingly appear irrational and intolerable.

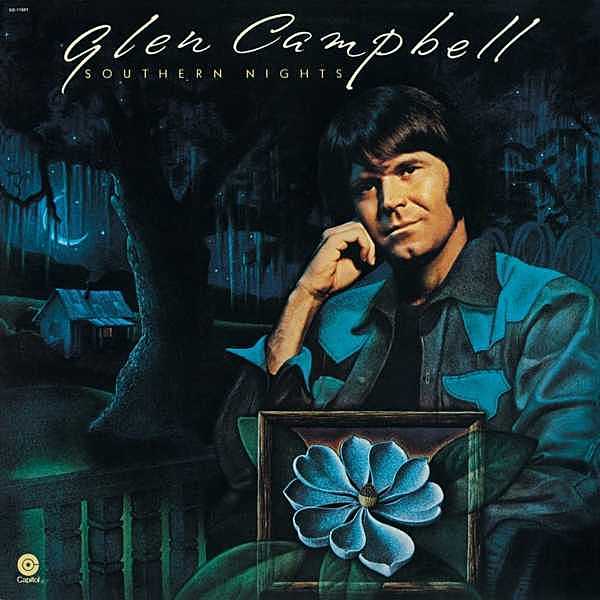

A digression: The second half of the 1970s was a golden era for Glen Campbell. After a series of albums languished in the depths of the charts, 'Rhinestone Cowboy' returned the country singer to international prominence in 1975. In the winter of 1977, Campbell continued his run with the release of 'Southern Nights'. The album was carried by its title track, a crossover pop-country hit that topped three separate charts. ‘Southern Nights’ tells a story of dixie innocence: memories of a thick, mysterious breeze passing through ancient trees, snatches of distant music and almost-recognisable fragrances. Campbell delivers this tale with a folksy, nostalgic charm that brings the listener to the Arkansas farm of Campbell’s youth, the location he claimed the lyrics evoked in his mind.

Except ‘Southern Nights’ had nothing to do with Arkansas, nor the Confederate-lite brand of antebellum nostalgia tapped into by the country star. Instead, Campbell’s ‘Southern Nights’ is a cover of a song by the legendary New Orleans pianist and composer Allen Toussaint. Toussaint’s heady mix of R&B, jazz, funk, and psychedelia tells a very different story to Campbell, and it comes from a very different context. Toussaint’s ‘Southern Nights’ is a gentle and soulful tribute to his childhood, when he would travel upriver, out of the city and into deeper Louisiana, to visit his Creole relatives.

Campbell’s cover is the worst kind of cultural colonialism. Toussaint’s introduction by way of intersecting keyboard melodies is replaced by a jagged country and western guitar riff. The piano trills – a signifier of Louisiana’s musical past through ragtime, jazz, and R&B – are usurped by blaring horn lines, backing vocals, and jangling banjo. Even Toussaint’s vocal delivery, modulated into an ethereal whisper that mimics the wind of the song’s lyrics, has been bastardised and brutalised into a hokey Southern drawl. Campbell took a personal story that was not his to tell, deeply rooted in a cultural context that was not his own, and forced it into a foreign space because it reminded him of a childhood it never belonged to.

This story is not unique in Western music. That is a history rife with the pillaging of aesthetic motifs and the decontexualised whitewashing of cultural specificities. Yet, to me, Campbell has always stood out as a particularly egregious example of this process. Partly, this is due to the Confederate connotations of his telling. Partly, it’s due to the distance between the sensitive, personal original and the brashly confident cover. But I think that mostly it’s because, despite myself, I can’t help liking Campbell’s ‘Southern Nights’.

I haven’t said all of this just to take issue with a 40-year-old song. I bring it up because, the more time I spent at Something to Behold!, the more I couldn’t stop hearing ‘Southern Nights’. Dick Frizzell has always occupied a Campbell-like position in my imagination. And it is important to recognise that this has not always been a fair appraisal of his practice, nor of his ever-shifting status in New Zealand art. It is easy to make a monster out of Frizzell, or if not a monster, a cultural cannibal at least. An ur figure of the New Zealand postmodern turn, the fact that his career has been borne aloft by the selective theft of other artists’ work has always been a feature, and not a bug, of his practice. One can easily take this approach, and weave it into a narrative where Frizzell – like Campbell – eats up what does not belong to him and spits it back out in a form that serves his own image and audience, at the expense of the original cultures and creators.

This is the mask of Dick Frizzell: Arch-Colonialist, wielder of the necromantic tools of state authority – whose very touch withers the authentic, only to resurrect it as kitsch. This is an image that he has, in no small way, built for himself. With his Tiki exhibition, Dick announced to Aotearoa that he was in control of those tools, that he possessed that power. It was also the place where he hinted at the seriality and continuity of his offences – that being a ‘bad’ painter and a ‘bad’ Pākehā (an epithet lovingly bestowed by Stuart McKenzie in the exhibition catalogue) would be the foundation of his practice. While Pop Art took the superficial pulp-imagery of celebrity and generated a kind of aura through repetition and alteration, Frizzell used the same process to strip the mana from taonga he held no claim to. This is the Frizzell monster, the Campbell-like appropriator, who repackages the culturally specific into accessible aesthetic generalities for a different audience.

While Pop Art took the superficial pulp-imagery of celebrity and generated a kind of aura through repetition and alteration, Frizzell used the same process to strip the mana from taonga he held no claim to.

At Gow Langsford in 1992, Dick transfigured and repurposed the tiki into an array of Western modernisms. In a consciously provocative act of double-appropriation, Frizzell assumed ownership of both the tiki (a generalised, malleable, and universal category in his work) and the modernist lineage, especially though direct quotations of Picasso. The exhibition’s strategy was maximum controversy, a fact disturbingly revealed by the catalogue essays. Each contribution, from Hamish Keith to George Hubbard and Robin Craw, is structured around an anticipation of offence. These paintings, and this show, were produced following the Headlands exhibition of April that year. In that exhibition’s catalogue, Rangihiroa Panoho’s essay ‘Maori: at the centre, on the margins’, inflamed New Zealand’s appropriation debate by accusing Gordon Walters of cultural theft. The Tiki essays constitute a series of pre-emptive retaliations against the criticisms of cultural annexation that the paintings were designed to elicit.

It’s difficult to argue that Dick’s strategy was not successful. Twenty-five years on, the show is remembered more as a formless controversy than a collection of individual works. In 2017, From Tiki to Tiki reflects on the exhibition as a moment in which Frizzell, master artist and intellectual provocateur, forced us to ask, ‘Who are we?’ and, ‘What is our culture anyway?’ Maybe he did. But Tiki also revealed Frizzell’s problematic brand of self-conscious positionality. The works, and by extension the artist, are defined by a colonial whiteness, by a notion of Pākehā positioned through opposition to indigeneity. The eye that produced Tiki – the eye of this mask of Frizzell’s – is ultimately that of Wakefield and Prendergast.

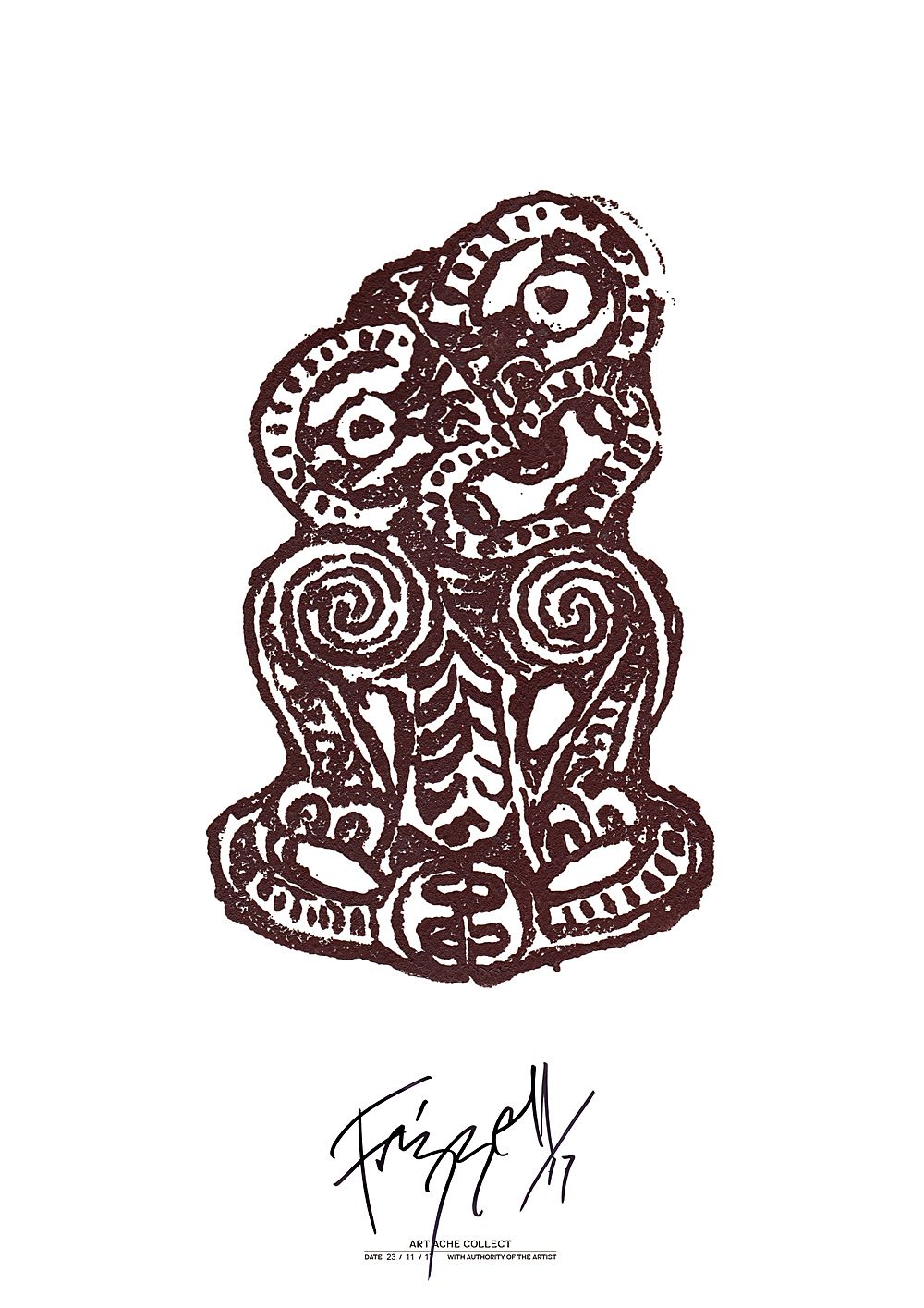

There are old eyes and new at Art Ache. From Tiki to Tiki consists of five prints, one by Frizzell himself. Dick’s print presents the tiki as a stamp – a conscious metaphor of his ideation of the form as a commercial and endlessly reusable motif. But stamps don’t last forever, Dick, the ink runs out. For the event, Frizzell was asked what the tiki represents to him. He responded, "tiki to me means 1992, when I first put the appropriation debate firmly on the cultural agenda with my tiki exhibition". His statement is as bold as it is incorrect. I doubt Frizzell is unaware of Panoho’s essay for Headlands, nor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku’s 1986 Antic interview which held similar charges of cultural theft toward Gordon Walters. But I can see where he’s coming from. Tiki was his answer to the appropriation debate – an unequivocal statement that in the post-modern, post-colonial (in some imaginations) world, everything is up for grabs and no subject should be out of the contemporary artist’s grasp. To Frizzell, Tiki was a gift to New Zealand artists. He smashed down the doors and said tiki are for anyone, and tiki are for everyone.

If you look closely, in the space between the words in Witehira’s print, you can find the real legacy of Frizzell’s 1992 exhibition: There’s a tiki-shaped hole in New Zealand art.

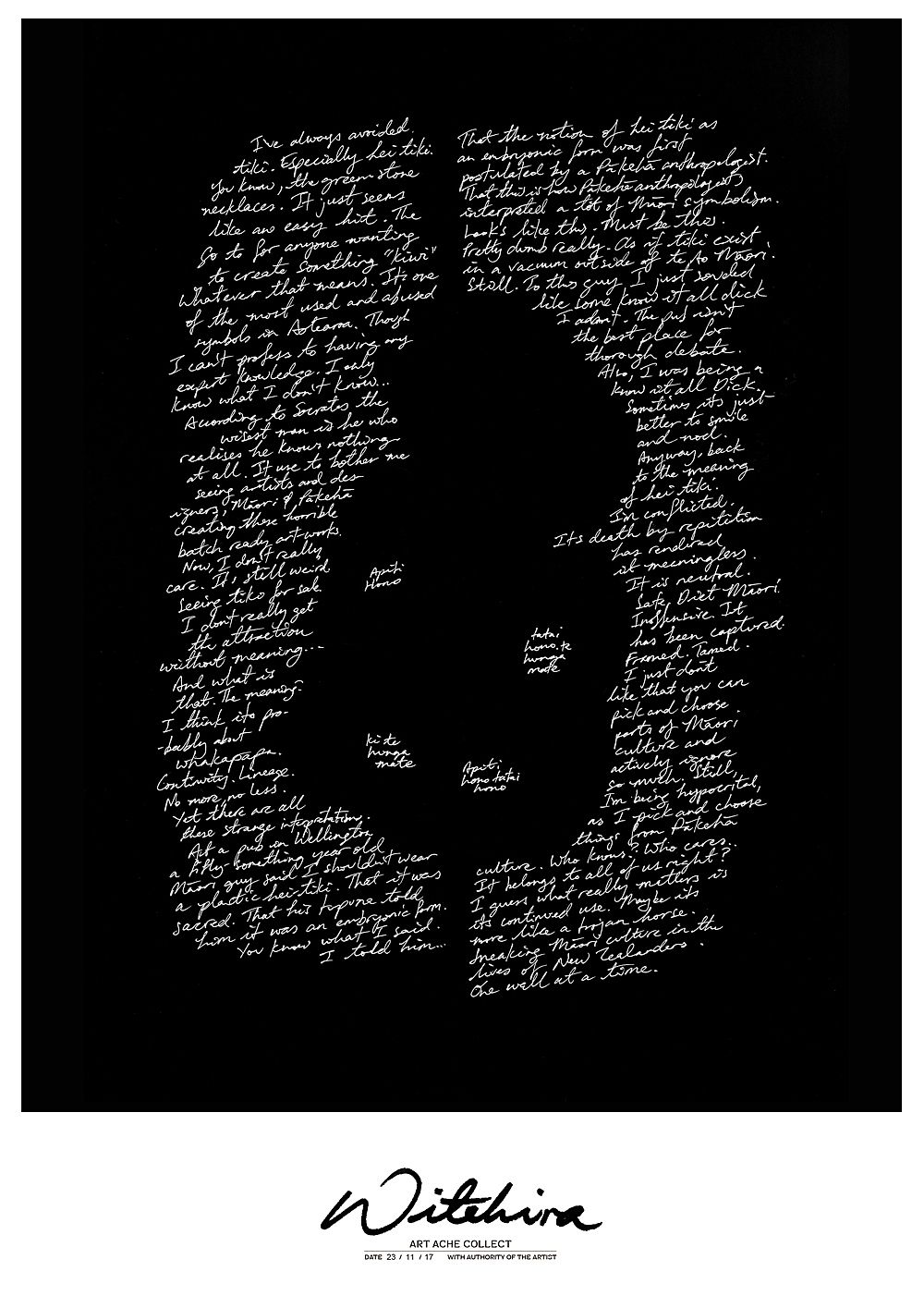

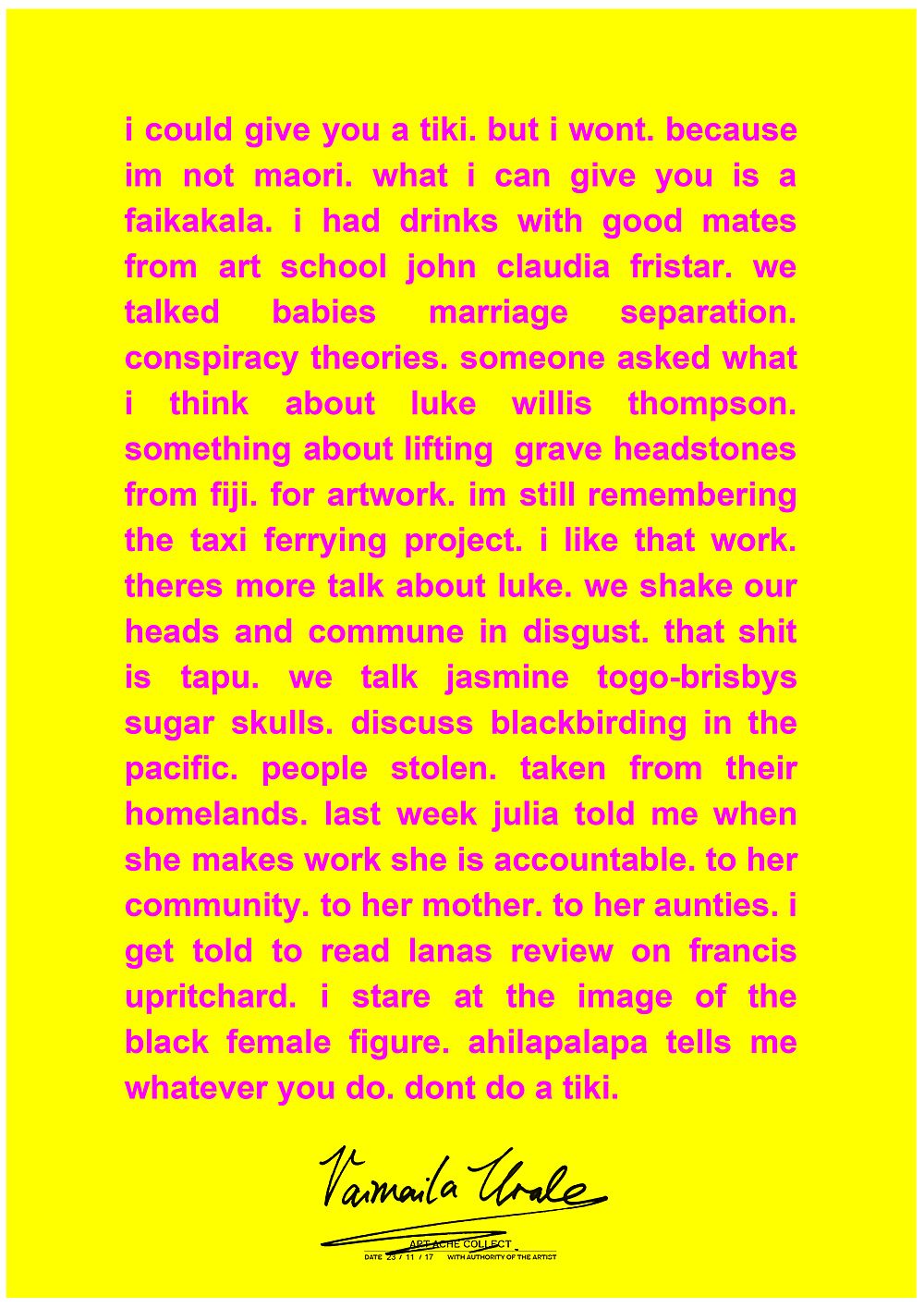

However, From Tiki to Tiki reveals that twenty-five years on, the scars of that exhibition’s success are still acutely felt in New Zealand art. Two prints in particular demonstrate that, instead of opening up the tiki to art and artists, Dick has, in many ways, shut it down. Johnson Witehira and Vaimaila Urale’s works are both text-based, the form of the tiki not appearing clearly in their contributions to the event. Witehira’s piece begins, "I’ve always avoided tiki," and continues as a meditation on his relationship to the form, his difficulties in addressing its use and overuse. The work’s text is split into two bodies, justified to reveal the tiki form in the middle. "Its death by repetition has rendered it meaningless," states Witehira. And if repetition was the murder weapon, it’s not hard to work out who has been holding it for the past quarter of a century.

Urale’s work doesn’t make shapes. Direct pink text on a yellow background reveals her own relationship to tiki, and the ways in which it has become a signifier of appropriation and cultural transgression in New Zealand art. The text moves from the tiki to the grave-robbing of headstones in Fiji, to cultural accountability, to primitivism in Francis Upritchard’s practice, and back again. However, the empathy and understanding demonstrated in the opening lines really says it all: "i could give you a tiki. but i wont. because im not maori".

I don’t want to talk for either artist, nor could I. But I will say that both texts instilled in me that same feeling I experience when I see Dick’s prints on supermarket bags and book covers. They point to the very real consequences of Frizzell’s twenty-five-year-old transgression. Instead of opening the tiki up, Frizzell has rendered it as an absence, or a non-space, in our cultural imagination. His repetitions have gone so far toward stripping the meaning from tiki for his Pākehā audience that they may have rendered the form unusable. It has become something to be circumnavigated, sometimes avoided, often ashamed of. If you look closely, in the space between the words in Witehira’s print, you can find the real legacy of Frizzell’s 1992 exhibition: There’s a tiki-shaped hole in New Zealand art. Art Ache should be commended for the inclusion of these works, and for the facilitation of this all too necessary conversation. But I worry that their inclusion within a framework of celebrating twenty-five years of Tiki is less of a challenge to Frizzell’s legacy than it is a confirmation of his ossifying status as our cultural provocateur. Yet even this, even the legacy both questioned and confirmed by From Tiki to Tiki is not the true Frizzell. It is an aspect, and not the totality, of his practice. However, at Something to Behold!, Tricky Dick may just have let the masks slip, and shown us his true face – and it is horrific.

The ten paintings displayed in Something to Behold! are a conscious return to pre-modernist academia, both in subject and scale. The enormous canvases (the largest measure 1800mm x 2200mm), painted between 2013 and 2017, display nineteenth-century artistic tropes such as floral still lifes, listless waterwheels, and cresting seascapes. Frizzell has written a short text to accompany the show, peppered with folksy colloquialisms that would make even Campbell blush. He calls these works "hero paintings", the essential cores of "sentimental art clichés". Frizzell hasn’t painted these to mock old ideas, but to celebrate what a century of avant-garde cycles have rejected. He wants to show us that "even shit has its own integrity".

Frizzell’s art historical potpourri is masterfully presented.

Let me get this out of the way. Some of these paintings are terrible. He has included three floral still lifes in the show. One, Flower Painting (2016), is really quite beautiful and has been executed with a degree of technical mastery in the emulation of Henri Fantin-Latour’s style that deserves approbation. The other two are just bad paintings. Asking $16,500 for an image that would be better suited to a brochure for a faux-Tuscan tile warehouse is a bit much. However, some of these paintings, like Flower Painting, are incredibly well produced. Moonlight Through a Breaking Wave and Swell (both 2017) are turgid seascapes that come straight from the playbook of Winslow Homer. Both are executed with a thick, incredibly concrete application that gives the paint a kind of post-impressionistic, three-dimensional quality. They are plastic, tangible, almost edible. Homer is there, but so too are Christopher Perkins and Vincent Van Gogh. It is a mishmash of domestic and international styles, each carefully chosen for their position on the cusp of modernism, just preceding its more radical innovations. Frizzell’s art historical potpourri is masterfully presented.

Standing in front of these works, there is something a little majestic about the scale and technical skill. They had me thinking that maybe there is some integrity in this shit, that maybe we left something behind when we relegated academic form and content to the past. But this is Dick Frizzell, and there is always something else going on. Dick’s paintings have always pointed away from themselves. The landscapes of the 1980s were not about the scenes depicted, but the supposed bankruptcy of the genre: the way New Zealand artists had tried to move on from and abandon what was once seen as an essential characteristic of our national art (to Pākehā at least). Even Tiki pointed outward. The paintings were not simple acts of appropriation as much as they were statements on appropriation – an envisioned coda to the nation’s attempts to grapple with Western modernism’s obsession with primitivism, and an attempt to launch himself into that evolving debate. ‘Let me be controversial,’ cried the Dick of 1992, ‘Me too! Me too!’

The works at Page Blackie also point away from themselves. By relentlessly repeating the motifs of the past, Frizzell is speaking to the artistic present. He knows that contemporary work is full of diverse voices, collective practices, and intersectional issues that escape the structures of the previous century. He knows, and he’s telling us that he does not care. As a collection, these paintings are defined by absence far more than presence – two middle fingers to a contemporary scene Frizzell is no longer a part of, and perhaps does not fully understand. The exhibition as a total statement is a deliberate intention to offend. Individually, this message is lost, and we’re just left with big paintings. Just as in 1992, Dick has attached himself to a Western lineage, reinforcing his brand of Pākehā as an essentially European categorisation. Except this time, it’s a reaction against that lineage. He wants to be seen as a New Zealander, an active participant in the decolonising project, not a ‘bad’ Pākehā. But what claim does he have to appropriating the French Fantin-Latour or the American Homer any more than the tiki? What intimate connection did he hold to the Spaniard Picasso? Two threads seem to be all that are left to hold his practice together: appropriation and white colonialism.

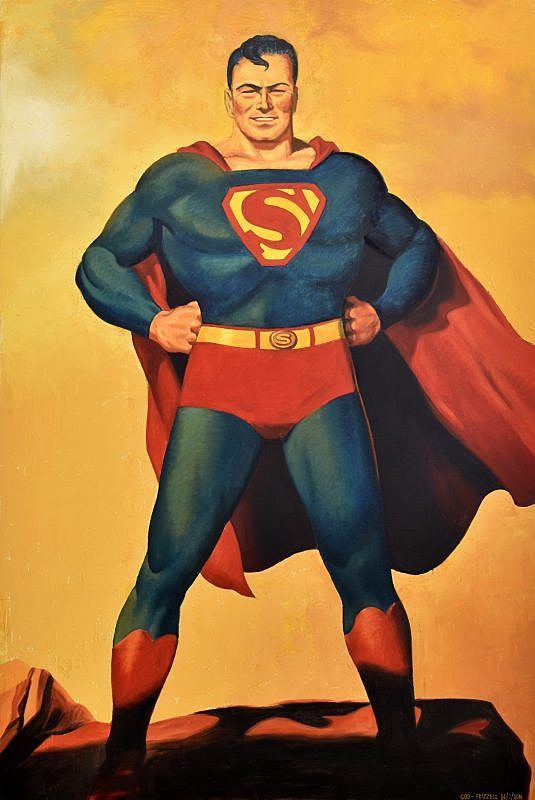

There is a painting of Superman in Something to Behold!, a stand-in for the individual, genius artist – the sole creative voice. Perhaps he is trying to manifest that spirit, perhaps he wants to mock it. I wonder sometimes if Frizzell mistakes himself for that spirit in New Zealand art. But Something to Behold! reveals that, if Frizzell is to be an avatar for a time and place, it is not from the nineteenth or twentieth centuries. No, here Frizzell lets all the masks fall away and shows us that he embodies a far more contemporary archetype. At Page Blackie, the artist reveals himself to us in bright colours and full form. Dick Frizzell: Troll.

His paintings are all jokes. Jokes that try to pick at and play with the perceived overreaches of liberal culture. Like the online troll that calls out safe spaces and trigger warnings as the excesses of an oversensitive national culture, Frizzell’s message is always, ‘grow up, get over it, and stop taking yourself too seriously’. Just like the troll, if you don’t find Frizzell’s jokes funny then you just don’t have a sense of humour – you can’t handle the ‘bantz’. And just like the troll, what is constantly excused as an intellectual exercise, a witty contribution to the debate, hides the foundations of a dark and insidious culture.

I make no excuses for Frizzell’s tiki paintings, they’re incredibly shameful acts.

A troll’s joke is always at someone else’s expense. The tiki paintings, ostensibly a clever way to make us engage with the formation of culture and the appropriation debate, gain their power from the exploitation of the taonga they mimic. I make no excuses for Frizzell’s tiki paintings, they’re incredibly shameful acts. Like Frizzell, I’m a Pākehā male. The two of us bear a responsibility for the sins of our fathers, for the systematic imposition of an oppressive patriarchal colonialism that continues to marginalise anyone that deviates from the perceived norm of the hetero white cis-male, including all people of colour. But through painting those images, Frizzell is complicit in the perpetuation of the colonial narrative, in the extension of that system’s dark shadow over Aotearoa and a refusal to address that responsibility. And I, like so many others, have joined in that complicity every time I’ve thought that those paintings were clever, every time I’ve engaged with the troll’s joke.

Something to Behold! is nothing new for Dick. It’s just another act of kitsch colonialism, this time in reverse. Once again, he collapses arts high and low at the expense of both, for profit and attention. The academic culture of the Old World is not his own, but the joke underneath is just the same. In Wellington, a new vision of the same pun is playing out. In Auckland, we celebrate the old joke in new ways. When I like listening to Campbell sing ‘Southern Nights’, I help the shadow of the Confederacy last a little longer. When I engage with Frizzell’s puns and jabs, I help the colonial equivalent last a little longer too. The price we pay for encouraging Tricky Dick is the expansion of a retrograde national attitude, a refusal to negotiate or confront the more difficult aspects of our country and our past. The price he pays is fame and fortune. And encourage him we do.

The paintings in Something to Behold! are displayed at the expense of contemporary artists. This is both a physical and a conceptual act. The constant lionising of Dick Frizzell – the $65,000 price tags, the endless prints and reproductions – is all a part of a slow but seemingly inexorable march toward the canonisation of our national troll. Not only does he take up space that new artists with new voices should have, but he openly mocks this fact in the exhibition. Something to Behold! was a journey for me. I went in expecting to see my old friend, Frizzell, the Campbell-like whitewasher and appropriator. For a moment, I fell for the show, seeing something in Frizzell I had not before, conceiving of his practice as far more external, much more than straightforward appropriative acts. But I left in a darker place than when I arrived. Glen Campbell actually wanted to make a product that people loved, and he wanted his audience to love him. The troll wants our attention, maybe even our approval. But this is not to advance any conversation or contribute to a discourse, he just wants to be seen. Where’s the critical potential in that? Why do these painted jokes deserve a place atop our artistic pantheon?

How complicit are we, as an audience of consumers, in the perpetuation of Dick’s kitsch colonialism? Should we call out every soul carrying a Countdown reusable, sporting a pair of Specsavers, or giving a framed Mickey to Tiki as a twenty-first gift?

Dick’s moment raises questions that we should all be thinking about. We actively discourage the social media troll, understanding that they have nothing productive to add to our lives or culture. Yet in the art world, our troll shines. What does it mean when Page Blackie gives Frizzell a solo show worth hundreds of thousands of dollars? What does it mean when Art Ache celebrates the twenty-fifth anniversary of Tiki? Outside the institutions of art these questions continue. How complicit are we, as an audience of consumers, in the perpetuation of Dick’s kitsch colonialism? Should we call out every soul carrying a Countdown reusable, sporting a pair of Specsavers, or giving a framed Mickey to Tiki as a twenty-first gift? Ultimately, these actions say that we are in on the joke, and we support our loveable troll. And our complicity in the joke continues to lengthen the shadows of our colonial past and present; of our inability to get past the issues of appropriation; of a nostalgia for the past that is behind us for a reason.

I left Page Blackie wondering about all the artists, all the voices, critiques, and ideas that could have hung on those walls instead of the endless repetition of the same old troll’s same old jokes – the same played-out delight in manufactured offence. I wondered when the institutions of New Zealand – artistic and otherwise – were going to gain the courage to sacrifice the commercially lucrative appeal of Tricky Dick in order to address these questions. I want to say the time is now, but I know it should have been long ago. What will take for us to say that Frizzell’s shit has no integrity? What is it going to take to finally turn off Glen Campbell, and let Toussaint play?

Something to Behold!

Dick Frizzell

Page Blackie Gallery

26 October 2017 - 27 November 2017

Art Ache at Golden Dawn

23 November 2017 from 5-8pm

Art Ache have published a page of FAQ's around the use of Māori tiki in the context of their event and the wider cultural landscape of Aotearoa.