Review: To Kill A Mockingbird

Auckland Theatre Company's production of To Kill A Mockingbird has the strong bones of the original, but a dated adaptation struggles to flesh the novel out to its true potential.

Auckland Theatre Company's production of To Kill A Mockingbird has the strong bones of the original, but a dated adaptation struggles to flesh the novel out to its true potential.

To Kill A Mockingbird is a classic. It’s one of the most respected and acclaimed books of the 20th century, and for good reason. It’s a deceptively simple Southern morality tale, bordering on a parable, distilling, as simply and as definitively as possible, what makes a good person and what makes a bad person. There’s no bad time to stage this; few entries in our own country’s theatre canon discuss racism in such a frank and understandable way. But where this production falters - and it is, for the most part, a strong, stirring production - is that it struggles to be theatrically relevant.

Auckland Theatre Company is working from Christopher Sergel’s adaptation of the novel, which he started in the 1970s and which premiered in the early 1990s, and it feels every bit a product of those eras. It is naturalism at its most comfortable and least inventive, with people talking ‘like we talk’ and moving ‘like we move’. It aims to reflect life as we see it and as we experience it, rather than theatricalise it or look deeper into it.

There are moments when you feel the production pushing against this naturalism. Andrew Foster’s raked stage keeps the cast constantly working against the slanted world that’s been laid out for them, and the wooden planks hanging down from the ceiling are a constant reminder of the world they have to navigate. It’s a landscape of death and discrimination disguised as a child’s playground.

While the script may be dated, it isn’t entirely a lost cause. Everything is in the right order, the story is ironclad and the characters are as strongly defined as they are in the book. But the novel’s biggest strength is that it puts us in the shoes of Scout, a child; the play can’t do that, not within the rigid boundaries of this brand of naturalism.

It’s hard to capture a very specific point of view with naturalism, especially that of a child. So we’re never put in Scout’s shoes; we’re as much a spectator of their experience as we are a spectator of the play as a whole. We don’t feel the huge shift in Scout as she experiences for the first time the world and its pointless cruelties; we merely see it. When Scout stands between her father and the lynch mob, we see it from the perspective of terrified adults, not just from a child just doing what she believes to be the right thing to do. It removes us from the story and it robs it of a huge chunk of its power as a result.

This means that the child actors have to work overtime to draw our attention. As much as the book is about these events from the eyes of children, Sergel’s adaptation is about these events from a distance. Our eye isn’t drawn to the children from narrative necessity so we have to have a reason to stay tuned into them and their development, rather than the adults and their more complex character arcs.

This means that the the trio of actors playing Scout, Jem and Dill have to work to get our attention; luckily for this production, the child actors do this effortlessly. They’re completely at ease onstage and they have an infectious chemistry with each other. We buy them as kids who would hang out because they choose to, not just because they happen to be in the same place. Flynn Steward is a particularly stunning Dill; he is entirely at ease on the massive Civic stage, with a charisma and fluidity that matches the professionals around him.

The rest of the ensemble play multiple roles, with Claire Dougan a clear stand-out. Dougan lends a hateable superciliousness to the WASP-y Stephanie and plays the ageing Mrs DuBose with the appropriate amount of camp hunchbank. Hera Dunleavy is as good as she’s ever been as the narrator; her warmth creates and fleshes out the world of the play. When she speaks, we see and feel the South.

Goretti Chadwick settles into Calpunia with an appealing world-weariness, while Kevin Keys is a suitably flat Heck Tate. Less successful are Scott Wills and Holly Hudson as the Ewells. Both make broad and stereotypical choices that reduce their characters to simpletons and cartoons rather than human beings, and the play is worse off for it. The story is robbed of complexity because we’re unable to see them as real humans, people with just as much life and heart as the rest of the cast.

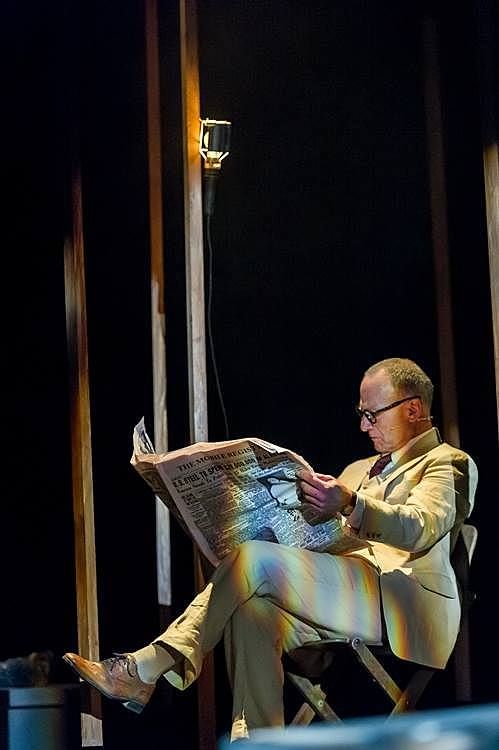

The actor with the hardest role, and the biggest shoes to fill, is Simon Prast. Atticus Finch is one of the most famous characters in all of literature; he’s a moral paragon, a font of wisdom, a role model. Prast’s Atticus is no saint; he’s a flawed and three dimensional-man. When he bullies Mayella Ewell on the stand, he’s genuinely terrifying and genuinely a bully. It would be easy to play Atticus as a perfect figure, but Prast goes a step further and plays him as a human, stepping closer to the complexities of the novel.

When To Kill A Mockingbird hits its marks - when Atticus is arguing so poignantly and truthfully for Tom Robinson’s life against the lies of the Ewell family - this is a stirring and heartrending production. It becomes a play about the ridiculousness of prejudice, and what stirs people into that prejudice. It becomes a play about a child realising that the world doesn’t work the way she thought it did, and the way her father thinks it should. It becomes a play that is still relevant and still real, especially when own our theatre is yet to address racism in a way that is as simple, plain and effective as, “There’s just one kind of folks, folks.”

But this is a story that deserves a great adaptation, and this production, for all its strengths and beauties, can’t cover up the fact that this isn’t that. We’re always stuck on the outside, and even though in its best moments the production reaches out and grabs us, it should have us well and truly in the shoes of Scout. To Kill A Mockingbird is about a child waking up to the world around us, but instead of waking up with her, we just watch her do it. That’s the difference between this good production and a great production.

To Kill A Mockingbird runs at

The Civic Theatre

from 8 May - 22 May at

For tickets and more information, go here.