Review: The Conch Trumpet

Adam Stewart reviews David Eggleton's melodious but shaky offering

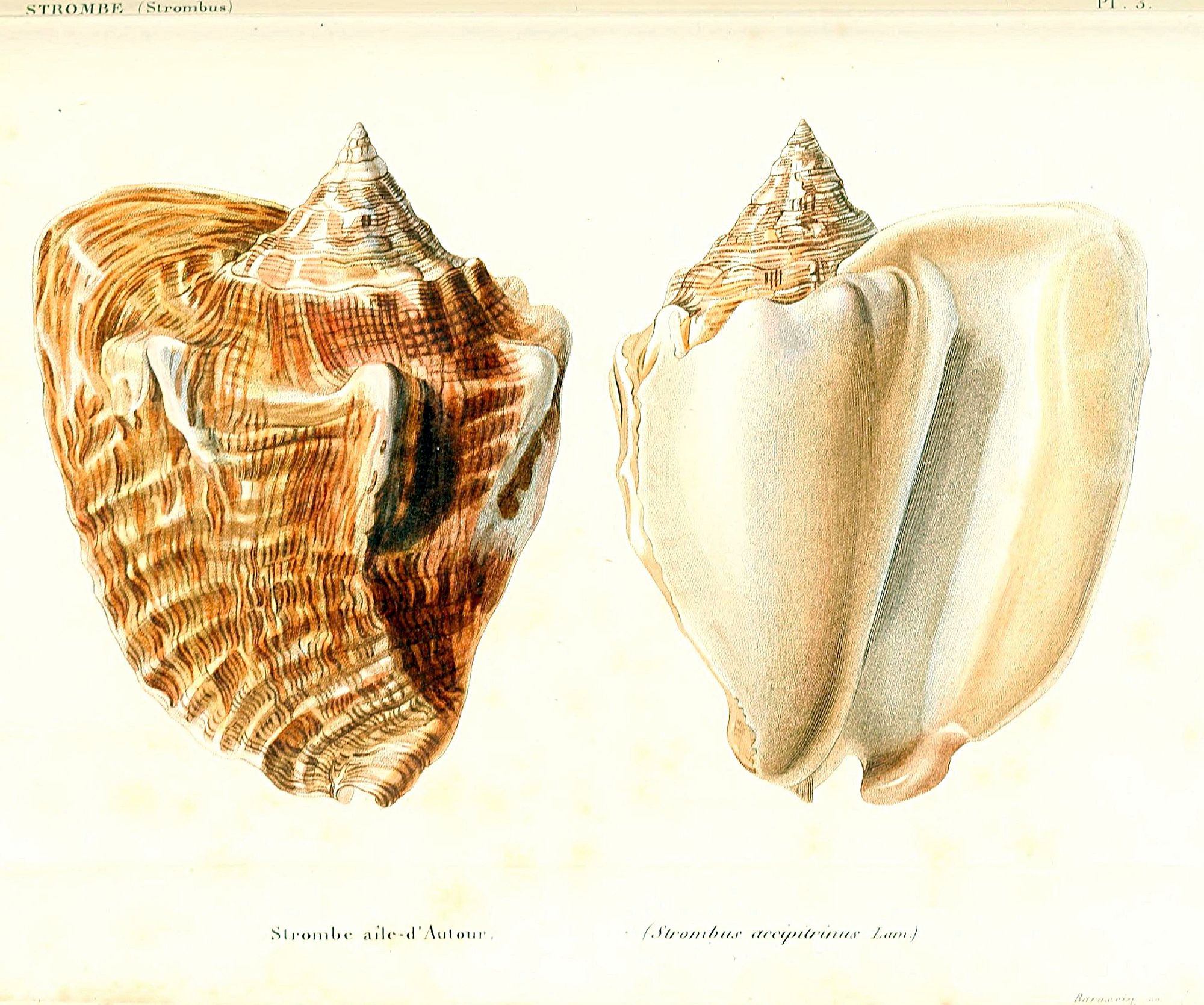

David Eggleton, Dunedin poet and raconteur, delivers a musical and travelling collection in The Conch Trumpet, his sixth and most recent book of poetry by Otago University Press.

Eggleton’s poetry remains truly fixed in the realm of song, ranging from word-game to political and social satire. However, the collection as a whole seems to sway awkwardly between New Testament and Shakespeare, the voice leaning towards the slightly archaic.

These aren’t inherently bad traits. Eggleton’s descriptions of nature conjure the elements and create hills and rivers as if for the first time. His Shakespearean lilt melds to a modern tongue, plodding measuredly in muddy gumboots like some kiwi Prospero, building his own island of words and light.

And there certainly is a kind of magic here. The book’s tempo is slow, with the longer line asking for the reader’s whole engagement, entering into a type of chant, an incantation of direct, eloquent world-creation. It's a voice that needs space to develop slowly, as if it were a print in a darkroom chemical bath, scarring and embellishing the imagination, fading in.

Eggleton is perhaps best known as a performance poet, and this collection does give away a few of the tell-tale signs of the stage transposed onto the page: sentences reel ahead of themselves, images are elasticised and weighed down with text, sometimes the poem lacks resolve or the sentiment of the poem isn’t made entirely apparent -- what Eggleton himself calls ‘just word jazz’. In reading works that were prepared for performance I often feel a disconnect from the voice, from the true nature of the performer. Somewhere, hidden in this book, there’s a David Eggleton just waiting to leap out.

The collection as a whole seems to sway awkwardly between New Testament and Shakespeare

The book is divided into five parts, and through these chapters we see different variations of the poet-rambler, the magician-conjurer, and the lyricist. There is a loveable character in the romantic voice of the rambling poet, and as I read these poems I see David standing onstage at a Dunedin pub somewhere, black jacket dripping under the red lights, pint of Emerson’s ‘Bookbinder’ warm as the proverbial eel’s insides. But the poems should stand on their own, and this is maybe where the collection falls short.

Section five, entitled Fire, contains the most song-like, word-drunk serenades, with the poem Exquisite Corpse showing Eggleton at his most self-reflexive, open and engaging: “The exquisite corpse of the dreaming poet/ is shipped to France in a wooden kimono”. Eggleton seems to see his own bones here, of both the poem and the poet (“Tourette’s syndrome charmers, throats thick with glitter”), perhaps even sees himself onstage mimicking wise Prospero in the epilogue to The Tempest. But his is a Prospero that understands the definition between audience-world and play-world, and knows the importance of their meeting. Because it's here that Eggleton really interacts. He reaches through and asks for the audience to participate, to aid in the building of the poem. Rather than his regular flourishes of lyrical wordplay the ‘exquisite corpse’ deploys an argument, and in doing so produces some of the best lines in the collection (“You want a hex with that mojo, or a symphony / of self-assembling furniture? / I bask in the glow of your burning cookbooks.”)

It is in this wild way that Eggleton comes upon true thing-ness. Where the back of the book describes Eggleton’s grounding reality as his ability to represent ‘the thisness of things’ (the exhausting imagery found elsewhere; the over-abundance of consistent adjective), I find the poet’s meditation on things as they stand – confusedly, unexpectedly – much more appealing. The poem ends in beautiful synaesthetic nonsense: “Your message to calm a tuning fork, / Your memory of loyalty to graffiti, / Your half-baked sneakers – / Pull the pin on bubblegum.”

Lyrically astounding, this turn of phrase almost recalls Charles Wright. But this is a bridge that is not often crossed in The Conch Trumpet. As a whole, detail is often forced onto imagery. With the performance style of these poems naked on the page, the reader tends to feel as if he or she is being preached to. Often, the poet’s view is hammered into the reader, leaving no area for imaginative leaps. While the depth of Eggleton’s vocabulary is unquestionable, apart from a few repetitious words ‘pinwheeling’ between images, the lyrical flourishes of the magician/conjurer do attract distressing notes of smoke and mirrors. It is no surprise, given the thisness of these poems, that I became attracted to the shorter lyrical poems in the collection. With less text and more room to breathe these shorter pieces highlight some of Eggleton’s more spell-binding wordplay.

In the first section, Shore, Eggleton blows hard on his rhyme schemes, with internal rhyme bouncing throughout. I can see each of these pieces working well in performance, and find myself reading with this in mind, but the stand-out pieces go against the grain of Eggelton’s regular poetics.

This is evident in Raukura, which loosens its grip on rhyme, allows for internal rhythms to develop and for its words to reach beyond mere sounding:

River’s mouth is drowned,

When ocean surges, green

Below dark vaulted forest

as well as in Moriori Dendroglyphs:

green tongues lollop round branches

through wounds in bark with deep

affliction like tattoos freshly fingered...

This particular poem engages in a dramatic shift for Eggleton’s work and really stands out in this collection, exploring some tenets of writing for the page that escape much of its surrounding poems: the lower case alignments; the broken lines, non-punctuated, non-measured, but still employing his wonderful ear and fantastic musical voice. Elsewhere, similarly shortened lines and stark poetics make room for themselves, such as the poem Bounty, where simple metaphor does a lot of work (“Years stack up / like hymn books; / days run like rabbits”) and my favourite poem of the collection, River, which is beautifully composed, quiet, rolling, ‘bodying forth’, Eggleton creating a masterpiece of watery language that flowers from mountain to sea, the poem encompassing the land in a tiny flood:

Unfurl fern-scroll,

in light sing,

glance off things,

shimmer by swimmers,

swirl green as willows

stirring tips of summer;

surface under bridges,

while land turns,

to autumn,

where leaves freckle

The Conch Trumpet is akin to a score, the musical notation of a performance piece formatted to be followed by singers, ramblers, poet-actors, but not necessarily a collection of poetry made for the page. I still feel as if something is missing when I read these poems, some of them not finding their natural close soon enough. Where a performer might extend the material by standing under the stage lights alone, here, on the page, the extension seems more like literally drawing blood from a stone, a hill, a sunset. Yet other poems seem to end too soon, as if the jester himself is saying “you just had to be there!”

But then, perhaps that is what Eggleton is calling for the reader to do. To listen. The Conch Trumpet is, after all, a type of alarm. And, like our Prospero, the ‘exquisite corpse’ must plead with the audience to applaud his cautious traps in his own musical, magical language.

Which, after all, is just word jazz, right?

O, syncopate, you skid row skidders, you

stumblebums, you down-and-out park bench

beat poets on easy street, thinking of ways

to profit from an end-of-lifetime clearance.

Contrary to the book's blurb, it is not the Bard himself that shakes down here in the Pacific, but the character the bard is trying to impart: a shaky character, but nonetheless full of music and wicked sorcery.