Dancing With Hikule'o: A response to TongPop Herstory

essa may ranapiri meets Hikule'o, Queer Goddess of Pulotu, in Telly Tuita's exhibition TongPop Herstory at Weasel Gallery in Hamilton.

essa may ranapiri meets Hikule'o, Queer Goddess of Pulotu, in Telly Tuita's exhibition TongPop Herstory at Weasel Gallery in Hamilton.

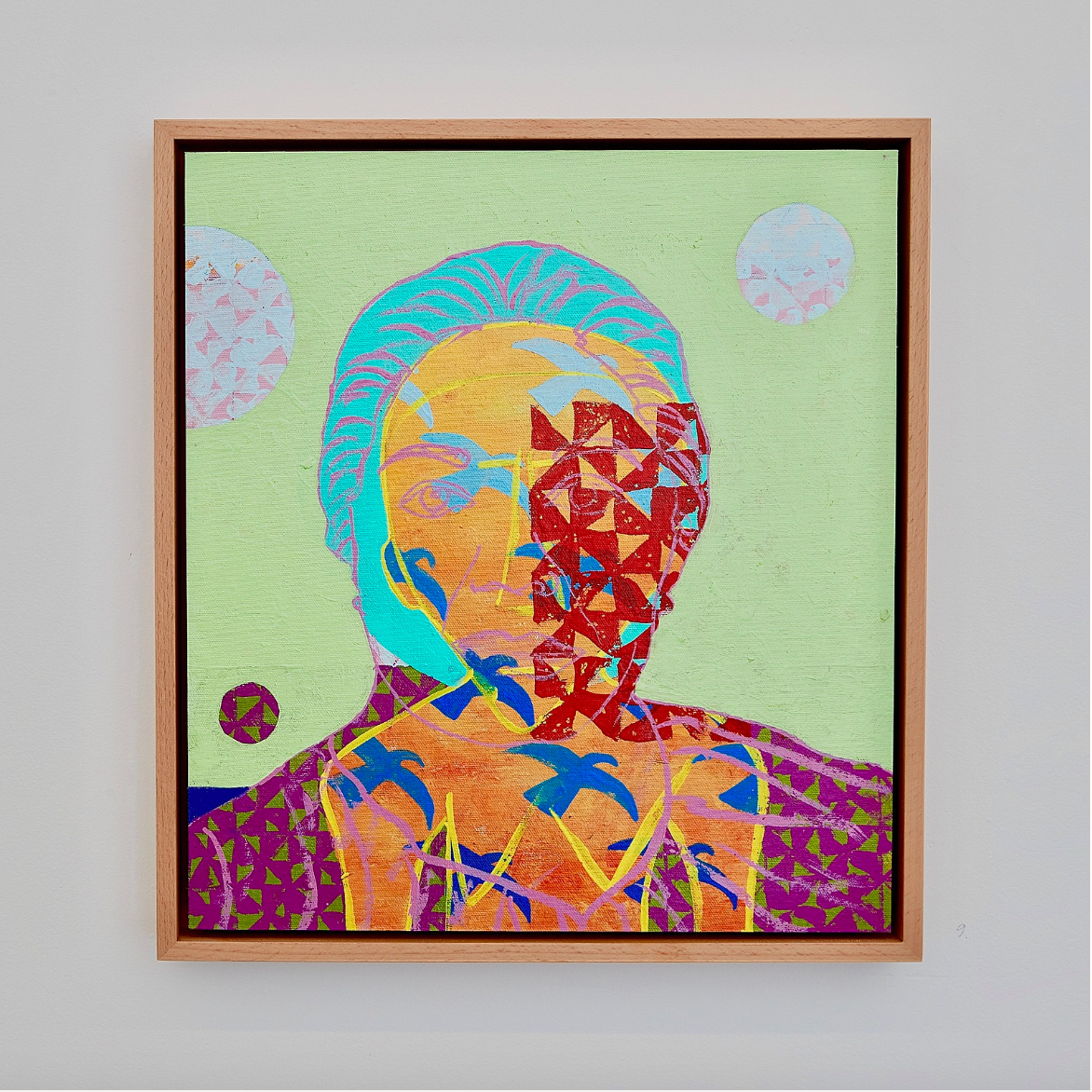

There is a plastic bowl sitting to the side of the door as you enter Weasel Gallery, full of shells and little plastic dinosaurs all painted in a vibrant purple. The objects shine where they lie. The exhibition reaches out to you from the start. Come take one or two or three or more of these purple pieces, place them on top of the paintings that speak to you. Take part in the tribute to Hikule’o and her legacy. For if TongPop Herstory is anything, it is a tribute to the goddess Hikule’o. She or he or they (their gender is not fixed) is the god of the underworld – Pulotu – the world of darkness that people return to after life. What really struck me about this tribute is how much Telly Tuita resists the darkness; everything seems to dance with colour. The spinning flowers and tumbling birds evoked in the manulua patterns cascade across the background of many of the paintings, creating a landscape or backdrop that is not fixed, that is never rigid.

The bowl sitting at the entrance is a reference to the kava bowl, and ideas of storing and travelling (the kava bowl was also used for finding one’s place while navigating the seas). It ties together what would otherwise be disparate elements: the pop-art aesthetic; the traditional; the portraits of historical figures of complex reputation; the science-fiction injection of stargates; and the flat colour of triangles that immediately evoke great invading spaceships. Telly is greatly concerned with the alien, both in the way Pasifika and Queer peoples are viewed as alien by a cis-heteronormative settler society and in the way these settlers were and are also these alien invaders. Nothing is simple or simplistic here.

There are four paintings (part of an ongoing project of Telly’s) that make use of the John Webber etching of King Paulaho taking part in a kava ceremony. The etching – all dark lines and geometric spacing – carries with it the baggage of colonisation: Webber was one of James Cook’s crew members, tasked with the job of observing and recording these alien cultures. The image screams staged. It sterilises what would usually be a lively event, also erasing women from the occasion. Telly paints over prints of this image, rewriting the unwritten or the erased, pumping life back into the scene. Kava ceremonies were and are not sterile affairs; there would have been noise and laughter and movement, which the Webber etching goes out of its way to obfuscate through cold gestures towards objectivity. But nothing is as basic as the boxes colonisers try to put us in.

I knew nothing about the story of Hikule’o until I met Telly. One of the ways in which people celebrated and connected to their gods was, and is, through wooden carvings. These carvings were cared for, oiled and put to bed. A chief at the time, in a show of solidarity with the English settlers, had these carvings hung from ropes, a signal to the death of these deities and the welcoming of the Christian God.

Oddly, the painting that drew me in, in an exhibition full of colour, was Stargate to Pulotu – monochrome except for random bursts of yellow – the black lacquer of the stargate, the path to the underworld, as it smothers the settler’s etching. I’m standing there staring into the black mirror it creates. I’m standing there at the entrance to the underworld and there is so much life there! Te Korekore awaits. One day we will go back to it, and maybe we already are there, and already have existed in this space forever – it’s just waiting for us to make it.

Two other paintings speak directly to power: one that features a recreation in white lines of a bust that depicted a 20-year-old James Cook, before he became the man that would cause so much pain. He seems like an innocuous young man in this depiction. Another painting in that same style depicts Queen Sālote, who was the first Queen regnant of Tonga. These two paintings are layered with an effigy of Hikule’o standing behind the figures. Both of these people gained much from the banishing of Hikule’o and this is where the critique works its way back to Tonga, a place Telly feels has done so much to colonise itself. The knowledge that was once free, locked away for the Royal Family to covet. These paintings work to soften that power and to humble these figures.

Top: The Queen, 2020.

Bottom: Stargate to Pulotu, 2020.

This exhibition is far from prescriptive. A lot of the paintings are left to speak for themselves. There is a searching, open quality to the art here that really makes you want to move your body and dance with Hikule’o – but this is also because of how much culture has been lost. These blossoming colours and unsettled landscapes make something new out of the gaps.

When you look at Telly’s paintings they luxuriate in the maximalist, in the vibrancy of many things happening at once. In the hues colliding and complementing. They are a celebration. And a refutation and recognition of Tonga as it was, as it is now and what it could be, as the world could be. It all comes from a place of not knowing, because how could we know? After what the settlers did to us, and what we did to ourselves? It is about living inside that not-knowing and going Fuck It! We can create it here and now, for the future and for the past! For our mokopuna and for our tuupuna! These paintings are a guide over that uncertain sea.

TongPop Herstory

Weasel Gallery, Hamilton

26 February-21 March 2020

Feature image, top of page:

Telly Tuita, Red Alien Fleet, 2020.