Feminine Mystique: A Review of Soft Tissue

Ella Gilbert's solo show plays with ideas of constructed femininity. Jess Bates reviews.

Ella Gilbert's solo show plays with ideas of constructed femininity. Jess Bates reviews.

Soft tissue includes tendons, ligaments, fascia, skin, fibrous tissues, fat, and synovial membranes (which are connective tissue), and muscles, nerves and blood vessels (which are not connective tissue). It is sometimes defined by what it is not.

I’m not often seduced by the poetry of wikipedia, but seeing Soft Tissue at the Basement has got me googling. “Soft tissue” wiki helpfully informs me, “is sometimes defined by what it is not.” As a comedic meditation on the affectations of the ‘weaker sex,’ Ella Gilbert’s solo clown show Soft Tissue contains the same back-handed articulations and remains just as elusive.

The Basement loft is the barest I have ever seen it: the newly installed back hall through the double doors is lit with a graveyard blue and an eerie sequence of gendered calls echo from backstage. Like a sputtering dial-up tune, the sequence goes something like: giggle-giggle-mm-hmmm-mmm-hmmm-hack-splutter-hoot-hoot-cough. For the ensuing hour of feminine (and arguably feminist) clown work, this will be Ella Gilbert’s aural tool kit; a soundscape which has us laughing every time.

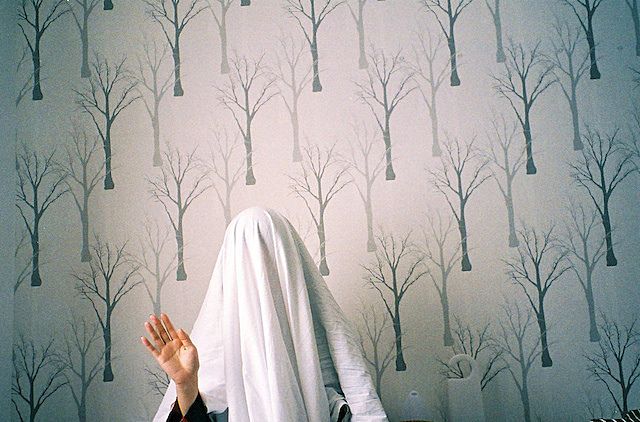

A playful, bandage-wrapped creature in beige heels minces out from backstage, as though through an abbey from the Sound of Music. She has the doe-eyed look and bonnet of the Baroness and the trembling lost lamb feet of Frauline Maria. Though her costuming references that unflattering nineties favourite, the boob-tube dress, the giant piece of tubular gauze from armpit to knee is somewhere between Parnell housewife and a burns victim, and considering the content – this hits the mark beautifully. Ella Gilbert plays the buttery-eyed victim to her own circumstance, bemoaning the ever-climbing length of her skirt and the little red grazes where her shoes bite at her heels. She pinpoints the damsel with perfection. We giggle with her at the performed distress.

The lovely tightrope Gilbert walks is that quivering membrane between virgin and whore that we know so well. Gilbert is captivating in the accuracy of her feminine mystique - the simpering giggle, the slight bob of the knee, the serene doll-like mask. But she peppers this with a highly sexualised feline character, rolling and spitting like cat-woman in a hurricane. It is a creamy combination, that she does well to slip so effortlessly between. Gilbert has a sense of comic timing that is fine-tuned, knowing just how far to push these archetypes before the room will crack.

Gilbert has a sense of comic timing that is fine-tuned, knowing just how far to push these archetypes before the room will crack.

Just as we reach critical mass on her glossy characterisations, Gilbert drops out completely - bouncing her boob-tubed ‘titties’ inches from the face of an audience member, to a dirty rap beat that is impossible to trace, but from which the enduring lyric remains, “there’s a voice coming out my mouth.” The moment is brief, but serves perfectly to pop open Gilbert’s nostalgic representation of the feminine. This is the contemporary grotesque of girl-hood that defines my generation, an MTV in-your-face sexuality, lacking all the poise and subtlety of its feminine forebears. It is a useful device for change in a room that is otherwise saturated by a cooing, simmering pussy-cat. When she whips out a pregnant belly to crump at another hapless audience member, the audience is delighted and shocked, all over again.

The best thing about Gilbert’s work, however, is her fearless clowning. Clown is a satisfying form for both it’s minimalism and its risk - it relies on the performer to be an acute listener, to hear the joke dying in the room and save it in the seconds before it expires, every time. The game of saving the show, with simple, silly ideas, must always be alive in the eyes of the performer. Gilbert’s clown, in all her curated feminine glory, is a perfect fit for the game between audience and performer. It is a clever alignment of both form and material. The feminine archetype asks, with every movement “am I beautiful? do you love me?” and the clown’s delight to perform is always “look! I am being a silly woman, do you love it?” The result is a form of drag that is both familiar and unsettling, the kind of doubly percussive performativity that Judith Butler would be proud of.

As part of this real-time conversation, Gilbert has a knack for casting the audience in satisfying ways; first as the parent or lover that might kiss her boo-boo, then as a pack of rampant dogs and finally as her providers; with big hope-drowned eyes she begs for “just a little bit” of food or drink. The second-night crowd is delighted to attend to her requests, charmed by her sexualised consent jokes (should she put one finger in her mouth, or three?) and the faux distress of her plea to “help me!” The discomfort sets in somewhere around the point I realise that there is no alternative voice in the show. Soft Tissue is a pillowy femininity set on loop. This is by no means unintentional, but it is certainly at times bleak. She fits three fingers into her mouth at the request of the viewer, despite her protestations, and remains delighted and aroused at the thought. Her coy pleas-for-help become an echo chamber for female tropes written by the male gaze, and the result is every bit as “confronting” as Gilbert’s marketing promises.

When Gilbert finally fulfils the prophecy of her song, and allows a full, grounded voice from out of her mouth, it is to begin a diatribe on the problems of the “staunch” woman. It is a tone with all the oratory of an inaugural address and begins to recall the “nasty” woman speech of this years’ Woman’s march. The importance of this moment is clear. Up until this point, Gilbert has spoken only in cute-isms and apologies, trapping sound like an effeminate Pikachu behind her teeth. To finally speak is a grand evolution for this character. I even think I hear a soft sound cue and I can feel the room change, as the audience sits forward in their seats. We are ready to move into the meat of Gilbert’s material. But just as it begins, this moment is thwarted. The new voice disappears, and we regress back to the poised and vacant woman, teetering and tripping towards us with a smile.

This is the crux of Soft Tissue’s enquiry: to truly say “no thank you” while remaining well-liked – that matrix of feminine etiquette that demands gratitude for a problematic patriarchal inheritance.

The arc of the show here begins to collapse. I can hear the real matter of the show, the terrifying voicelessness of feminine experience, knocking at the door, but not being allowed in. Yet Soft Tissue comes so close, and I must admit, I have seen nothing like it. Gilbert is closest to a sense of hope with her parody of an impassioned acceptance speech in the final third of the show. She gushes with gratitude for our part in pushing her, for believing in her, for holding her up, and then moments later is politely refusing the award completely. This is the crux of Soft Tissue’s enquiry: to truly say “no thank you” while remaining well-liked – that matrix of feminine etiquette that demands gratitude for a problematic patriarchal inheritance. This is perhaps comparable to Jacinda Ardern’s response to ‘the baby question.’ As a female politician, it is almost impossible to simultaneously play feminist values while remaining a media darling. It is impossible to draw boundaries for oneself and to also survive.

Like it’s name, this work in Soft Tissue is one of many layers – the feminine becomes both a means to exploit the performers needs, and the trap that prevents her from any real autonomy. My regret is that this fleshy problem was not used to close the show. The choreographed dance and missed joke that sit in its place feel like a work-in-progress ending. However, as the operator executes a twenty second fade on a single abandoned shoe in the middle of the stage, I cannot help feeling the muted intelligence and deep hilarity under the work. Soft Tissue is an original and articulate enquiry into uncomfortably familiar territory. As I wander down the stairs, I check my baby voice as I address my partner, and wonder if I’m more embedded in the sticky, voiceless swamp of softness than I might think.

Soft Tissue runs from 26-30 September at Basement Theatre. Tickets available here.