Love Letter to Timberlea: A Review of Riverside Kings

Natano Keni and Sarita So's Riverside Kings is a nostalgic journey set in the Upper Hutt suburb of Timberlea.

Natano Keni and Sarita So's Riverside Kings, directed by Natano Keni,is a nostalgic journey set in the Upper Hutt suburb of Timberlea. Maraea Rakuraku reviews and discovers an exciting new voice.

There are so many moments during the performance of Natano Keni’s Riverside Kings where I throw my head back with full-belly laughter recognising characters, situations and the play’s underlying emotional drive, that I’m in danger of neck strain. I’m not alone, evidenced by the similar responses in the theatre throughout its 75-minute run.

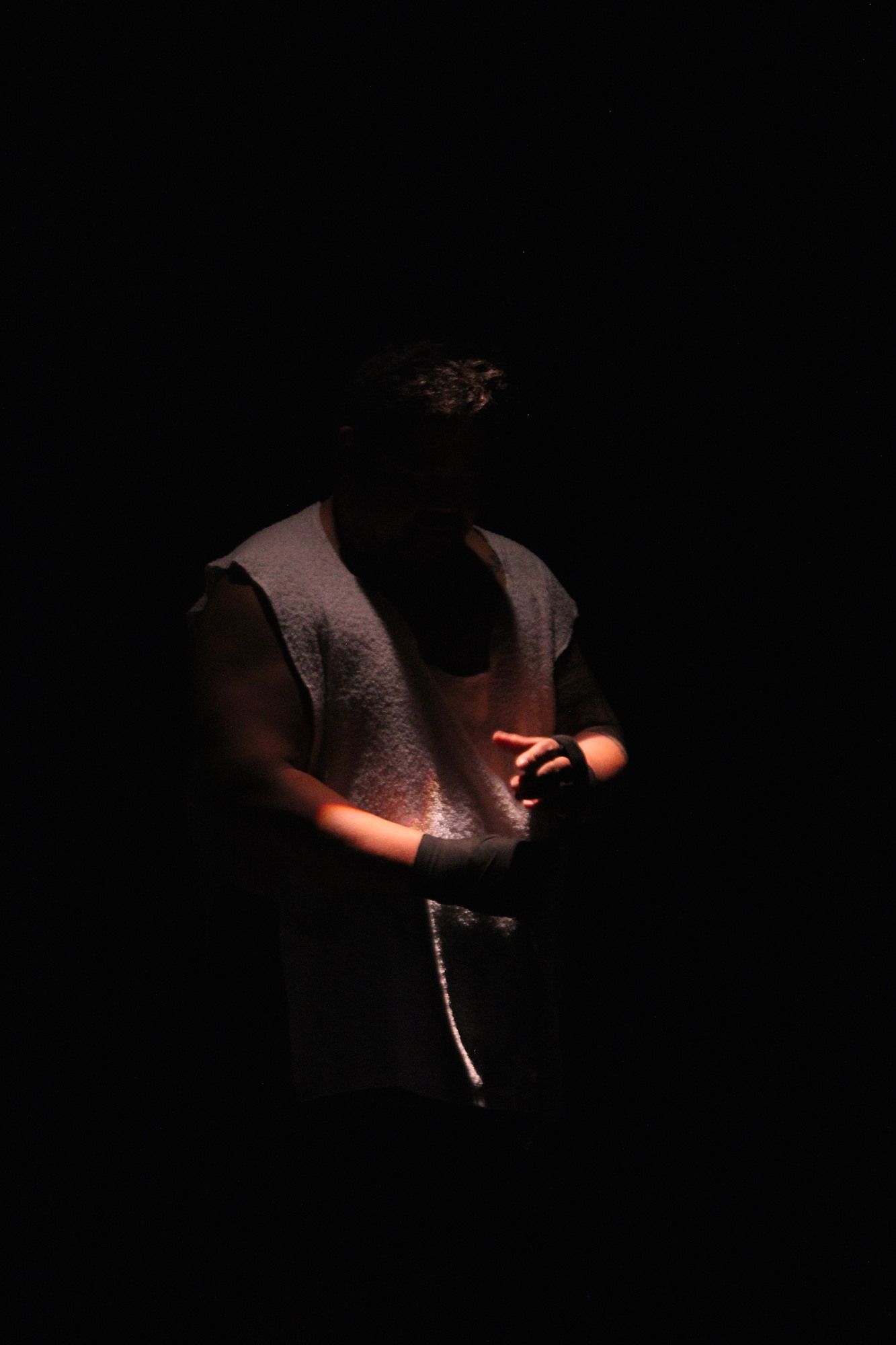

Elvis Presley crooning as we enter the theatre sets the tone for what is to follow. White painted stones mark out a lawn boundary, punching bags hang from a beam, and stylised wooden trees make up the set. As the lights dim we hear karakia with shout-outs to Whiskey the Cat. Then in a slow-motion movement that gradually picks up in speed, we watch Semu Fillipo, as Peni Tala, international boxer, wrap his wrists as part of his warm-up routine. A pumping soundtrack, strips of lighting that could symbolise railway tracks or a boxing ring and we’re off, from the International Boxing Circuit to the Upper Hutt suburb of Timberlea.

Semu Filipo, and Lale Ausage (in an impressive debut performance), play four characters between them; all are Samoan men with the exception of a Māori man, Elvis, who talks pretty much non-stop, doesn’t carry a judgmental bone in his body and fancies himself as the self-proclaimed Mayor of Timberlea. Contrast that with Peni (tricked into coming home for Christmas by younger brother, Salaki), who has more than a few hangups about being home, being from Timberlea and possibly a smidgen about being Samoan. Then there’s the fiesty, always-got-a-smoke-dangling-from-his-lips, Amo who isn’t so much an older mentor, but more an adventurous uncle who’s just as likely to clip your ears as strip to the waist and stand next to you, machete in hand, facing a brawling mob.

It’s through these characteristions that the story of these ‘gods’ as Elvis puts it, unfolds. Throughout the story we see the four men preparing an umu, teasing each other. They reminisce about a Timberlea where Māori and Pacific Islanders lived, worked and played side by side; when you knew everyone in the street and running in and out of each others' houses was the norm.

But times have changed and it’s through the arrival of Peni from the international boxing circuit that we’re given insight into long ago that world is for these men now. It’s clear Peni is haunted by a tragedy, but what that is, not so much. When it is revealed, while understandable, his anger and judgment towards those around him, who do everything to welcome him back into the fold, makes that particular thread hard to follow. Realistic to life though it is, I struggled with this a bit; as any professional boxer will tell you, anger has no place in the ring. And it’s not useful outside it either. Showing anger that way seems obvious, and when the reveal takes place, overwrought.

Neverthless, Elvis jollies all of Peni’s negativity along while sparring with Amo. As soon as I hear the word ‘mahi' when Elvis first appears, I brace myself for the ‘dumbed-down’ impersonations of Māori that some Pacific writers like peddling. What a relief it is to see a Māori character that isn’t a Geoff da Māori from Brotown, or Romeo’s family in Romeo and Tusi.

Writers Natano Keni and Sarita So offer a new generation’s commentary on those relationships. It sees more in our commonalities and shared endurance of a dominant white culture. Through all those trials and tribulations, whether shared on factory floors, foresty trucks or on roadsides raking asphalt, there is solidarity, respect and love. Keni and So have done a terrific job in portraying that world through dialogue that is hilarious and uncompromisingly true to place and character.

Snippets of Peni’s boxing career punctuate the story, played effectively and powerfully. While beautifully lit and interesting, I did want this boxing element to either be more connected with the primary story more distinctly separate from it. When Amo mentioned something from a previous boxing scene, I thought, "ah this is it!" but its resonance was so light that just like that, it was gone. These scenes serve as Keni’s self-professed homage to boxing, however in its current state, thematically they don't necessarily reflect that. However on reflection some days later, I'm wondering if they have to; it does nothing to distract from what is an accomplished piece of writing and direction.

Of all the characters, Salaki Tala is the one least is known about (although there are mentions of unfulfilled boxing and rugby league aspirations). I’m not even sure it’s an issue, but alongside the richness of the other characters he’s in danger of almost disappearing. Even so, when key emotional moments occur, such as when we realise the source of his brother's anger, he’s the one anchoring the scene.

The actors spend alot of time looking outwards, to the landmarks and neighbourhood of Timberlea which is juxtaposed so beautifully with a story that invites us to look in. It’s the power of writing from the inside out; when the insidious, proprietory gaze forever applied to you and yours is negated through authenticity. Because you’ve lived, live or you are it. It’s the sweet spot. A place many are desperate to be where truth is recognisable in dialogue,action and characterisation. Elvis is so wonderfully evoked by Ausage that it’s a little disarming, as I recognise aspects of my brothers and cousins in his carriage and physicality. His good naturedness and talktalktalk is so true to Māori men I know, who don’t want for much, love kids they haven’t fathered, and their life satisfaction is shaped only by as far as their eyes can see.

This is the transformative power of hearing places and people relevant to you onstage. It creates space, whether you’re aware of it or not.

The shout-outs to place names and local identities contribute to anchoring the work in place, and I can imagine it must have been thrilling for those in the audience who’ve lived or live there, who are familiar with events and its people. This is the transformative power of hearing places and people relevant to you onstage. It creates space, whether you’re aware of it or not.

There are clever stylistic choices, for example when with the flick of a wrist, a hammer turns into a boxing ring microphone. The lighting (Glenn Ashworth) and sound (Karnan Saba) design contributes to an experience that can only be described as the unveiling of some serious talent. And what stellar casting. Both Filipo and Ausage are equally matched as performers. What’s so impressive is that this is Ausage’s debut performance. He's an absolute joy to watch.

While Riverside Kings is a Samoan story set in the Upper Hutt suburb of Timberlea, it could just as easily be transported to Tokoroa, Kaingaroa, Murupara, Kawerau or any similarly populated small town supporting a primary industry like forestry, where Māori and Pacific Islanders first started rubbing against each other. And in that friction, a cross-cultural exchange is taking place; the gentle ribbing that can just as easily turn into a full scale fight, the intimate knowledge of each others histories and the equal parts piss-taking of cultural practices (like haka) and reverence of others, like the building of the cookhouse and laying of the Christmas umu.

Seeing stories like this onstage contributes to the unveiling of the understandings we have amongst each other and a revealing of the inter-relationships between Māori and Pacific Islanders that isn’t confined alone to the migrations of the 60’s and 70’s.

Riverside Kings is a love letter to Timberlea and a spectacular debut, on all fronts (writing, directing, performance and production) and with the growth and development that only happens with seasons and touring, may it’s stretch be wide, in this heralding of the arrival of a new Pacific voice.

Riverside Kings runs from June 13-17 at BATS Theatre, Wellington. Tickets available here.