Fear and Chicken Bones: A Conversational Review of Ranterstantrum

Lana Lopesi and Kate Prior pick through the rubble of Victor Rodger's powderkeg play.

Victor Rodger's Ranterstantrum premiered in the New Zealand Festival in 2002. 15 years later, Aucklanders are treated to its first season in Tāmaki Makaurau at the Basement Theatre. Some would describe it as a black comedy, but that's like calling the film Get Out purely a thriller. The play begins with a violent home invasion and spools out into pressure-cooker narrative exploding racial politics in New Zealand.

Editor-in-Chief Lana Lopesi and Theatre Editor Kate Prior pick through the rubble of the powderkeg play.

While we steer clear of specific spoilers, the review contains brief discussion of some general narrative shifts earlier on in the play.

Kate Prior: So what were you thinking about after the show last night?

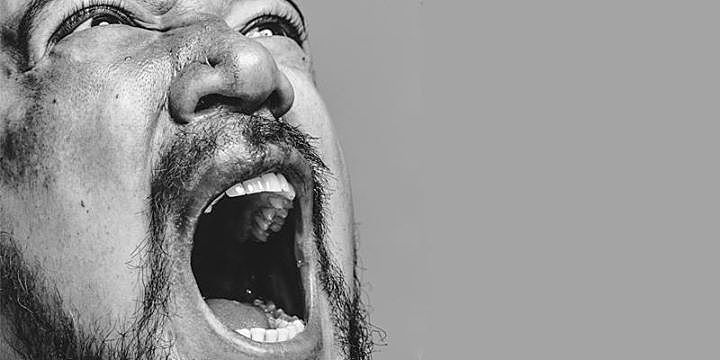

Lana Lopesi: I was incredibly fiery in the belly, enraged I guess, but not because I disagreed with the nature of the play, but because I totally understood the experiences and characters, to the point where it was as if Victor Rodger had gone in to my head and transposed everything I think and situations I have been in or witnessed, for the stage. I felt like Victor had said it all. So I guess my thinking after the show, was just, yes! But I also think perhaps I wasn’t the audience for it.

KP: Do you think it’s aimed at a Pākehā audience?

LL: Yeah totally. I mean I also have to say that as a Pacific woman I felt incredibly stimulated by it, and I also appreciate seeing stories of my own people, but I think that the play’s laying out of complex relationships, ideas around ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Pākehā, and unintentional bias and assumptions – those are things I understand incredibly well from first hand experiences, but it’s Pākehā who don’t necessarily see both sides of that conversation, but I could be wrong.

KP: I know what you mean. Like, even if I, as Pākehā, can have a theoretical understanding of these concepts, within a majority culture I don’t necessarily live them consciously everyday.

Even if I, as Pākehā, can have a theoretical understanding of these concepts, within a majority culture I don’t necessarily live them consciously everyday.

KP: But also to that, I’d say that there’s always (hopefully) going to be different experiences and understandings in an audience, and chucking those ideas into the crucible of a play and having all of us sit down in a room together and watch each other watch it (as is the case with the traverse staging in Ranterstantrum), that the act of that, no matter our familiarity with the concepts, is like, the powerrrr of theatrrrre.

LL: I thought the simplicity of that set and audience facing audience was really compelling. It made the audience’s reactions a part of the work.

KP: Yeah I think that traverse staging is a good solution for this play in the Basement with minimal space. It's fittingly claustrophic and voyeuristic.

LL: Absolutely. It also makes me conscious of my own reactions. Like, what am I supposed to be laughing at or not? Or shocked by?

KP: Yeah, I love that about watching the watchers – you become aware of your own need to navigate your reactions with the reactions of others.

But to go back to your last point about audience, I agree, it does feel that in writing Ranterstantrum, Victor squarely has in his sights the Palagi woman in his dinner party story who told him he looked like a savage when he was eating a lamb shank. Which as he mentions, served the spark for the play.

LL: Yeah exactly, and in the play that character is Lee – she feels like the primary audience.

KP: But interestingly like any good playwright, he has a fair bit of sympathy for Lee as well I think.

It reminded me how little I feel like I see these real clashes of racial politics in our theatre. And I don’t mean cute parries for comedy value, but opinions that feel deeply embedded in character vulnerabilities.

LL: I can see that – I overheard a conversation as I left the theatre where a group really resonated with Lee and Max. Personally I found myself hating all of them, even with Victor’s careful treatment.

KP: I think how Victor gets inside his character’s heads is what hit me the most. It made me realise that I often see work that, no matter how well it veils it, has a very clear implicit standpoint – a kind of singular voice. But the whole point of drama is that we feel stretched by multiple empathies right. Seeing Ranterstantrum again really reminded me how little I feel like I see these real clashes of racial politics in our theatre. And what I mean by that is embodied and extreme dialectics – the push-and-pull of big-stakes standpoints. And I don’t mean cute parries for comedy value, but opinions that feel deeply embedded in character vulnerabilities. It's 15 years after it was first performed and it still feels rare for this to happen in New Zealand theatre.

LL: This is the part where I have to say that I was only 10 when it came out the first time…

KP: Oh shit that makes me feel old!

LL: …but those ideas are definitely still relevant. While I can’t say that I was a very politically or racially aware 10-year-old, I know it’s relevant because I’ve had to defend myself in similar conversations. But to go back to the push-and-pull – he made that push-and-pull happen with the audience too though right, whereby at a certain point in the play you realise that you too were relying on your own assumptions.

KP: Yeah he uses the reveal of information so deftly to reveal our own prejudices.

LL: Absolutely!

As a Pākehā person in the audience, you're not comforted. You're implicated.

LL: We mentioned that the social issues have not changed much, but I'm interested to know what differences, if any, there were between the 2002 and 2017 productions?

KP: Do you know I actually couldn't put a ring around significant structural changes (and I'm not sure there were any) but having seen the first season at the more traditional theatre space of Downstage in Wellington (now Hannah Playhouse), I do think something about the low-fi Basement Theatre quality works for it – it feels more urgent.

LL: As in maybe it’s not a mainstage play?

KP: Perhaps not a mainstage play now, weirdly. It’s so great that Downstage in the New Zealand Festival was its first season. But I think because it was in a festival setting it could hold that level of risk. That word is overused – what I mean here is it's a play, where, as a Pākehā person in the audience, you're not comforted. You're implicated. I can’t imagine an Auckland Theatre Company or a Court Theatre staging a play with that level of risk now.

LL: The idea of mainstages being conservative in terms of race politics scares me a lot! Although it’s no different from our large contemporary art institutions so I shouldn’t be shocked.

I just don't see that kind of craft around a specific kind of rage anywhere else on New Zealand stages. Like, the knife Victor takes to racial politics? No, no one else does that.

LL: I have a question, I walked away last night thinking I need to go to more theatre, and that was amazing, but I think that’s rare right? That Victor is one of the only people making this kind of stuff. It’s not reflective of New Zealand theatre? Or is it?

KP: Oh man. Good question. I definitely think we don't see that kind of craft around a specific kind of rage anywhere else on New Zealand stages. Like the knife Victor takes to racial politics? No, no one else does that.

LL: That’s a shame!

KP: But there's plenty of great, different work in that territory. Miria George or Mitch Tawhi-Thomas' work is an example. Come to more theatre Lana! Lol. But yeah, nothing with quite the same acid as Victor. Which is also why his work is so powerful right, because it’s a unique voice.

But I’d really like to hear the 23 year-old Victor of 2017 you know?

LL: Totally!

KP: Do you feel like that level of assumption and casual racism that’s at play in Ranterstantrum is still something you would encounter in 2017?

LL: Absolutely! All the time. Every day. The "do you know that random other brown person?" thing is a very common question I get, as well all sorts of assumptions about how I live, my upbringing, my family and my class. Although of course I do need to say that I’m mixed, so I do benefit from various levels of white privilege. But that level of racism – it’s everywhere.

The "do you know that random other brown person?" thing is a very common question I get, as well all sorts of assumptions about how I live, my upbringing, my family and my class.

KP: Initially the pretty painful character of Scott (“Indians smell like curry”) felt like such a caricature but no, I've heard guys like that. And because of that tribal mentality, where everything becomes ‘bigger’ because of the one-upmanship power of a group, the reality is a bit like a caricature.

LL: Totally, but by the end of the play he was my favourite Palagi. He said everything that he thought and, as crude as it was, it was on the table. I think Victor successfully reveals the danger of a ‘good’ Pākehā, as in the character Bridget, who was potentially the most painful (and familiar) character for me. That archetype thinks they are being an ally but can’t actually see their own assumptions and casual racisms so therefore can’t acknowledge it exists.

KP: But is she an archetype? And do you mean ‘danger’ of being ‘good’ Pākehā because of her inaction around certain antagonisms?

LL: The ‘good’ Pākehā is definitely an archetype, it’s a conversation I have behind closed doors with POC friends all the time. In Bridget those casual racisms included the low-key slagging off of the Samoan character Joe throughout, the casual use of fob, or coconut, or the laughing around Joe being subservient but not actually doing anything to change that nature of servitude. And it all came to a tumbling end when Joe was left alone on the stage. After everything he had been through that night, the victim was always going be left as the perpetrator.

But bigger than that it's exactly what you said about her inaction, that kind of teaching of cultural competency is not Joe’s responsibility, it’s Bridget’s – that’s Pākehā work. And sometimes I can’t help but think that it’s a Pākehā problem. As in those with privilege don’t know how to share dominance, so that’s where racism and prejudice comes from. Which is why I think the play was for a Pākehā audience – to make obvious the trauma and oppression that is happening unconsciously.

Why is it so easy to prioritise one trauma over another, one person over another?

KP: Yeah I agree. But also I think what's so interesting, and something that we haven't talked about yet, is that Victor throws up a core tension between two traumas: the rape of a white woman and racial oppression. And I think it's pointed that he does that, playing into white hysteria around the idea of Pacific and Māori criminality. But yeah, it means there’s loyalties at play there – for example, those between sisters versus those between friends – so while I understand there exists the archetype of a ‘good’ Pākehā, it’s this sense of an archetype that doesn’t sit so well for me in the context of the play, because it seems like a concept, and it doesn’t seem to speak to what the writer is mining – the interplay of loyalties and vulnerabilities and fears that foster these microaggressions.

LL: Exactly, so I'd say why is it so easy to prioritise one trauma over another, one person over another? I would argue that one is easier to understand as a trauma, and one is more expectable to dismiss.

KP: What do you reckon the playwright’s questions are, or some of the questions that the play raises?

LL: I think we’re being asked to take a focused look at ourselves, and the way we understand each other. Things like are we really free of assumptions and bias? Or perhaps no questions but more just shining a spot light.

What do you think?

KP: Yeah, and also this thing of what tells us (Pākehā) what is a 'good' POC? You know, how all of a sudden, Joe is 'safe', he's 'cool', but a minute before he was a threat. What does that mean? Why is he that?

What is the danger? What are we afraid of?

What is the danger? What are we afraid of?

LL: Yes! Why are we afraid?

And I also found it interesting how Joe so quickly and comfortably played subservient roles, for example, in serving food. Why is that so normal?

KP: Yes absolutely, those role shifts are so interesting. Because then he'd become this sassy focus of the group when he'd get to tell his 'gay stories' – like that's more permissable or something.

LL: Totally, because the gay Pacific man is less ‘scary’ then the straight sexually aggressive one or something like that?

KP: Yeah! It's just so great that Victor flips the context of character. For instance, we have to spend that painfully long amount of time with Joe being misconstrued by Palagis Lee and Max as the ‘aggressor’, but then he becomes an accepted friend. However because of where we began, it means that all that tension that erupted initially still seethes away underneath the ‘comfort’.

Also what I love about this play is how Victor has his characters just in casual bants – where they're all using this really racially-charged language in different ways: as mates; as jokes; as an underhand pejorative; as out-and-out insult. And that relates to what you were saying about the language Bridget used – it wasn’t in a vacuum. This was language that the group had normalised; this weird matrix of jokes and insults. That was definitely present for me – the interplay between extremities of hate in individuals, but then that kind of acceptable, soft, group hate, which appears in other ways, but is still there.

For me also, there's something in the play about legacy of pain.

God it’s such good writing! Still, 15 years later, no one jabs in a sharp knife of prejudice and turns it quite like Victor Rodger.

LL: Absolutely. This play is contemporary because these traumas and biases steam from deeply rooted histories. And I’m scared to say it, but I think it will always be contemporary for that reason.

KP: God it’s such good writing! It’s a play with such classic suspense and bait-and-switch elements so as to be narratively satisfying, but it’s so dense with political provocation, black comedy and incisive rage. Still, 15 years later, no one jabs in a sharp knife of prejudice and turns it quite like Victor Rodger. We're lucky it has another season, and in Auckland. It's unmissable.

Ranterstantrum runs from August 1–12 at The Basement Theatre. Tickets available here.