Efflorescent Abstractions: A Review of ‘Outflux’

Ellie Lee-Duncan reflects on Clara Wells solo exhibition at Skinroom.

Ellie Lee-Duncan reflects on Clara Wells solo exhibition at Skinroom.

The material and the immaterial. The tactile and the fleeting. The location-specific and the effacing of site. These oppositions flicker like frames in a looped film, reappearing throughout Clara Wells’ recent solo exhibition Outflux at Skinroom Gallery, Hamilton, which featured a spread of paintings, drawings, animations and film material.

Wells is a motion and time-based artist working from her home city, Christchurch. Preferring object-making over digital, Wells paints or bleaches her 18mm film, and transforms the media of documentation to painterly exploration. Over the oppositional elements and various media, even in the static paintings, there is an emphasis on continual flow.

Using water from the river and ink, these works were created in Hamilton.

In the first gallery space is Waikato River #1-5, a series of paintings on paper depicting the weaving path of the Waikato River. Using water from the river and ink, these works were created in Hamilton. With a light handedness and wet on wet techniques, there is an element of chance, allowing the paths of fluid to move unattended and form rich tonalities and eddies, swirled in pollution brown and black. Unstretched, the paper buckled slightly in response to the water, creating a tangible suggestion of a landscape. This is furthered by the mountainous shadows created between the top corners of each work with angled lights placed on the floor.

Wells recently returned from a six week artist residency at the Parramatta Artist Studios in New South Wales. Prior to arrival, she wondered if geographical parallels could be drawn between Parramatta and Hamilton. Both were built with a river at their centre, and both are satellites to a larger, major city (Sydney and Auckland respectively). She chose instead to focus on the specificities of space.

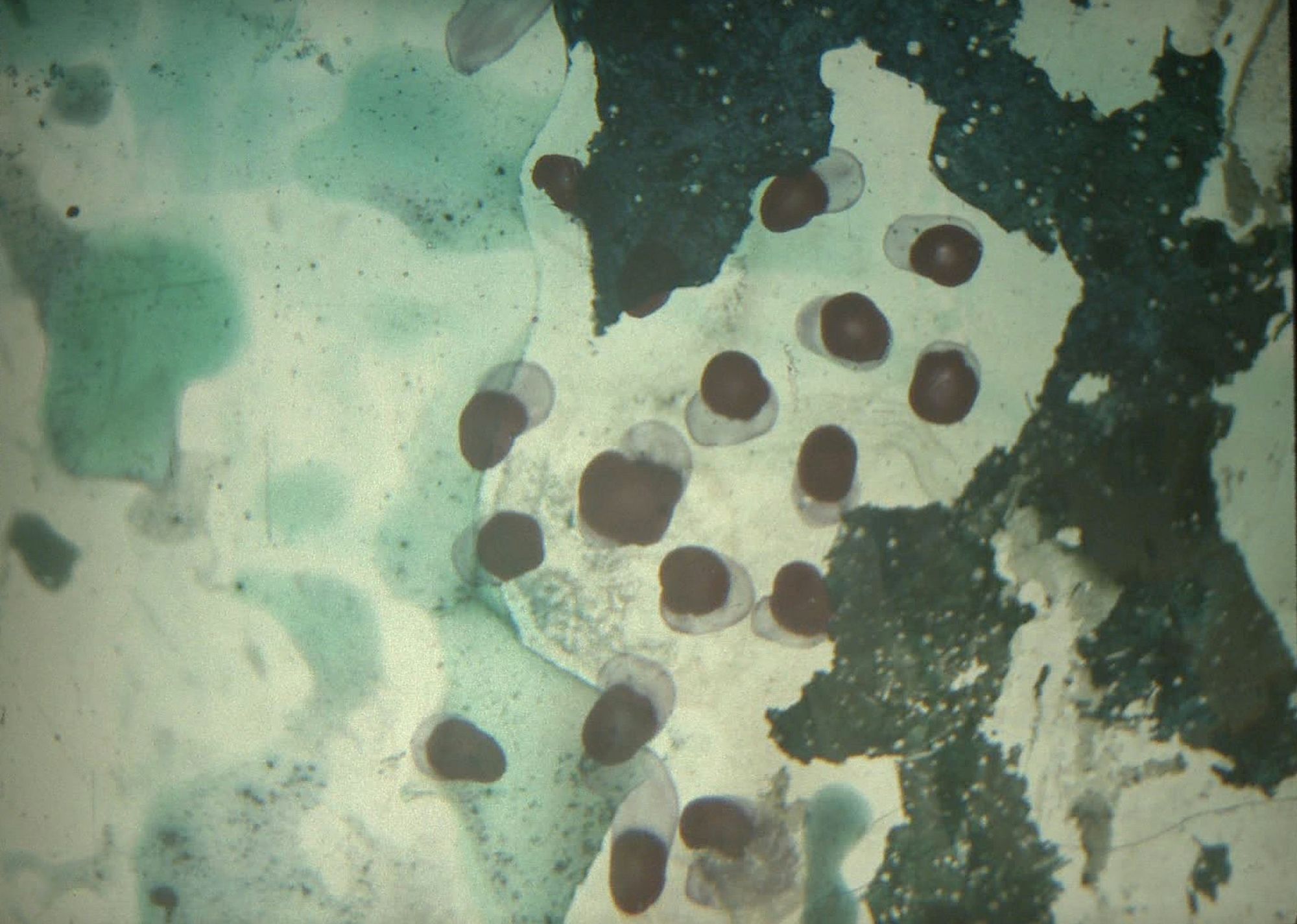

Wells created the film work, Anguilliform during this residency, which shows a flowing, curvilinear form which is a simplification of the Parramatta eel. The name of the city originated from the name of the Darug Indigenous peoples of that land, the ‘Barramattagal’, and that name derives from the word for eel, ‘para’ or ‘barra’; and water, “matta” or “mada”. Jakelin Troy, the Director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research for the University of Sydney, observes that Parramatta was named from ‘Barramatta’ which can translate as “plenty of eels”, “eel waters” or “place where the eels lie down” (similarly, Wells’ title derives from the English scientific name for eel, ‘anguilla’). The work linked the power of naming and the significance of this animal to Indigenous identity. Wells painted onto the 18mm film as a direct animation, and submerged it in a handmade emulsion. When viewed as a strip the film shows the distinct individual eel forms; when the footage is projected, the frames blur into swelling and ebbing lines, the flowing motion of the creature.

The work linked the power of naming and the significance of this animal to Indigenous identity.

Through her monochromatic works, the second room of the gallery revealed a vast installation, Barefoot Hamilton, a physical pulling apart of her work. Streamers of vivid green, purple and pink film were hung in a web. A projected video on the end wall illuminated the colours on the celluloid, creating gem-like gleams through the film, a dazzling kaleidoscopic array of colour. Here, the film strip unfurled and we could see the actual eels in the roll for Anguillaform, and gum tree leaves repeating in another. In this, the animation process, normally unseen, is shown as the work itself and the structural qualities of film are unveiled. When viewed, these carefully repeated drawings turn into a blur of soft suggestions. As Wells said, “the leaf itself is not seen in the frame, only the periphery of a leaf. So, you have to think about what it is in an entirely different way”. While in traditional narrative animation there is no sense of the artist in the finished product, here the physical personhood and hand of the artist is revealed.

The painted strips were a declaration of handmade mark-making and the nature of film itself, rather than the end product. The video work Barefoot Hamilton was projected onto the end wall – the digital file was transformed by a projector into colour and light – as light, projected back through the layers of draped plastic film. It was an overlapping of technology, a transference of media and format. This room constituted a sanctum sanctorum in which we are fully and physically immersed in the tangibility of Wells’ practice and surrounded by fleeting calligraphies of shadow and light.

Back in the first room, a black and white stop motion video work, Parramatta Automatic presents the viewer with gritty, indistinct forms. It refuses cohesion in its loosened animation, like a Len Lye animation. Created in Parramatta also, the finished work is made from a series of paper rubbings created as Wells walked a length of one kilometre through the city. At various points in her journey she would lay a sheet of paper over the landscape and rub over it with oil pastel, creating a ‘grounded’ image of the topography. While the technique, frottage, was famously used by the Surrealists, Wells’ intent of using it here is different.

Surrealist rubbings were dislocated from the form they were made against. They were chance fragmentary abstractions, reduced to formal qualities alone, or were reinvented as a texture within another artwork. While Parramatta Automatic does delight in the aleatoric elements of the work, it is still an essence or experience captured in the location itself.

Each point Wells decided to record is an attempt at preserving, ordering, and re-presenting the location, and the uniqueness of the land.

Each point Wells decided to record is an attempt at preserving, ordering, and re-presenting the location, and the uniqueness of the land. Set to a track by Annie McKinnon, the sound maps a city, which is then autogenerated and spat into a track, like the happenstance nature of the street. It becomes a motion of indexical recording at each point. The gravel, the grit, the cigarette butts and tyre tracks, are all in a specific space as a result of intervening forces, or as the direct residue of others existence. The laying of the paper, the documenting of the presence, and the rephotographed paper are then arranged into a video archive, flashing abstracted forms; suddenly Well’s journey is flattened into frames, sped up into a rush hour, indistinct haze.

In ‘Walking in the city’, a chapter from his work The Practice of Everyday Life, French philosopher Michel de Certeau says, “To walk is to lack a place. It is the indefinite process of being absent and in search of a proper.” Although Wells’ work lacks a singular place, we could consider it instead as mindfulness, a continued process of being persistently present. Through the motion of indexical recording, Wells documents the presence of place. In doing so, as with her eel and river works it refuses the singular in favour of repetition, and reiteration. This continuous replication of elements and patterns lose their recognisability when animated. The rate of the frame per image does not match the size of the pattern, so the figurative nature of it becomes altered beyond recognition. However, the indexical essence, (whether recognisable or not) remains, a continuation that frustrates articulation.

Outflux prizes the emotive effect and atmosphere over objective recording, the collective over the individual, mark making over digital, handmade over machine. In Clara Wells’ works, the shift of space is not only documented, but refigured as continuous, wherein the fixed points are removed in favour of celebrating the flowing, the motion itself, the continuation, the continual. By necessity, it is always grounded in the tangible, the physical, even as the end result of a film strip, as a video enables a disembodied experience. It exists as an archive of spatial and temporal snapshots, but also as an archive of Clara’s own individual experience and emotional exposure of the land.

Skinroom

28 April 2017 – 13 May 2017

All photographs courtesy of the artist