Pull up the roots: Review of ‘On the Origin of Art’

Doug Dillaman gets the inside perspective from Brian Boyd while digging into MONA’s bold attempt to present great art that advances evolutionary theories of its origin – or is it the other way around?

Doug Dillaman gets the inside perspective from Brian Boyd while digging into MONA’s bold attempt to present great art that advances evolutionary theories of its origin – or is it the other way around?

Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), in its short tenure, has quickly transcended notoriety (from “that place made by some rich guy with a mummy and a poop machine”!) to become, at the very least, a provocative influencer that is increasingly difficult to ignore. With its latest exhibition, On the Origin of Art, co-curated by Geoffrey Miller, Mark Changizi, Steven Pinker and Brian Boyd, MONA aims for nothing less than changing the way the art world talks about art.

You are in a cavernous hall. Before you are four entrances, each darkened. Above each is a mysterious glyph. Which door do you enter?

The state of art theory in the early 21st century – at least as MONA tells the story – is one where cultural theory around art’s origin largely rules the roost. In this narrative, art is simply a product of the culture that the artist emerges from, as that is all that has shaped said artist. MONA’s research curator and senior advisor Elizabeth Pearce argues (in the introduction to the On the Origin of Art exhibition catalogue) that “this is barely seen as ‘a position’ at all, let alone called upon to defend itself”. And so, in the tradition of great shit-stirrers, MONA has done exactly that, mounting a four-pronged attack of “bio-cultural scientific philosophers”, as they’re modestly called, who contend that the roots of art are not in culture, but in evolution.

Professor Geoffrey Miller believes art arises from sexual signaling, ostentatious displays designed to attract mates. Think of the peacock’s showy tail, or the bowerbird’s shiny nest, and Miller claims it’s more or less a straight line to Pablo Picasso’s incredibly busy bedroom. Evolutionary neurobiologist Mark Changizi notes that our very alphabets are most likely to be constructed from symbols that appear in nature, and suggests that art is also borne from a mimicry of what we find in biology. Pop science author and psychology professor Steven Pinker argues that art is a by-product of other evolutionary advances, rather than a genetic change in its own right, comparing it to cheesecake. It’s something that satisfies us but is hardly encoded in our DNA. And then there’s Brian Boyd.

You choose the second door, so as to avoid the crowds. You have entered Brian Boyd’s exhibition. You have chosen wisely.

Who the hell is Brian Boyd, you may ask? He’s a professor of literature at Auckland University, perhaps most famous as a world-class Nabokov scholar, handpicked by Nabokov’s wife Véra to catalogue her husband’s archives. He’s equally obsessed with Karl Popper, an intellectual biography of whom is one of his current works-in-progress. He edits a book series [Evolution, Cognition and the Arts] as well as being the author of On the Origin of Stories, which is in part the inspiration for this exhibit. In addition to the similar title (both nicked from Darwin, of course), his book, which argues that humans have art in general and storytelling in particular as a result of an evolutionary adaptation, is required reading by MONA staff.

I met Boyd in December, a few weeks after visiting the exhibition, to find out more about how the exhibition came to be. It turns out he had no idea his book had such pride of place at MONA until he read the galley proofs of the (massive) exhibition catalogue, although he’s been on first-name basis with founder David Walsh since he invited Boyd to visit in 2012. “Right from the start, David’s idea was to have at least four co-curators proposing their own hypotheses on how evolution helps explain art, inviting us to select works to illustrate our theories, and to challenge the other co-curators so that it would be a scientific knockout competition of hypotheses.”

And so, Boyd came out swinging.

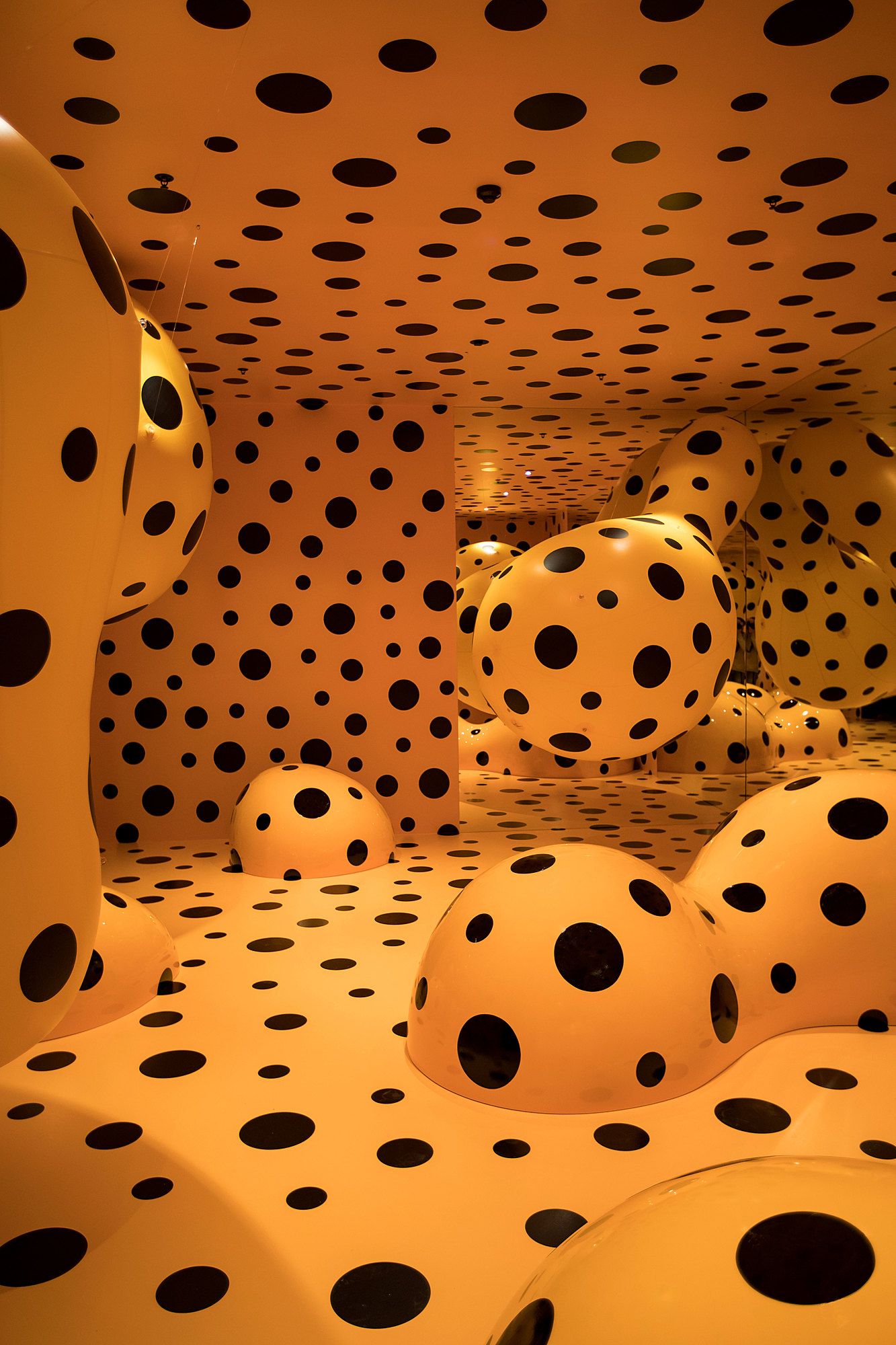

Boyd’s exhibition begins with a new commission by Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, a stunning bright yellow room festooned with black dots and featuring various organic forms (also yellow, also dotted) hanging from the ceiling and emerging from the floor, extending outward with the help of mirrored walls.

“I knew that I wanted Kusama right from the beginning. She fits so perfectly into my hypothesis that art is cognitive play with pattern. Because of the simplicity of the dots, pattern is in your face, and it is clearly very playful. Art emerges out of physical kinds of play, but because for humans our big advantage is in our mental command of things, we engage in mental play, and because brains operate on pattern recognition: that’s play with pattern.”

If you use the audio guide – Boyd, a generous host, recorded three hours of material for his exhibition – you’ll hear Boyd taking to heart Walsh’s instruction to challenge his co-curators, as he suggests that his fellow co-curator Geoffrey Miller’s theory of sexual signalling could hardly be relevant to Kusama. After all, her only significant partnership (with Joseph Cornell) was sexless, she’s aged well past her reproductive years, and she voluntarily lives in an institution - yet is driven to spend her two hours outside of said institution creating these artworks.

“My problem with Geoffrey is that he wants to use sexual selection to explain absolutely everything that’s interesting about humans. He wants to make it the sole explanation for art. It’s an explanation that doesn’t get to anything interesting in the artworks, and doesn’t seem to lead to a rich array of possible arts. Kusama’s clearly not appealing to males to try to fertilise her. So she’s perfect both to make my case and to make my case against the other co-curators.”

A disadvantage to MONA’s non-hierarchical approach to entering the exhibition is that, without having a sense of the arguments of the other curators, it’s challenging to work out whether said curators’ arguments are being fairly represented. And indeed Miller – whose own curatorial selections err towards the gleefully salacious, such as Jeff Koons’ Manet, a photo showcasing him about to perform cunnilingus on his then-wife Ilona Staller (aka porn star/Italian politician Cicciolina) - argues that sexual selection doesn’t explain everything about contemporary art, as his theory is simply about origins. But while Boyd may not give due diligence to Miller’s theory, his principal remit is to advance his own thesis – and, of course, provide an aesthetically satisfactory experience. From that perspective, Kusama’s Dots Obsession (Tasmania) is a perfect introduction.

Boyd immediately goes back to the very beginnings in his second room. If art is indeed an evolutionary adaptation – a genetic change that marks us apart from our predecessors - then it’s important to outline both the similarities and differences between human activities and the artistic qualities of those lower down the evolutionary ladder. Giant photos of pollen seeds, butterflies, Japanese paintings of birds and cherry blossoms, and Fiona Pardington’s giant photograph of kereru wings remind us that patterns are located deep within nature, while an intricately carved spear-thrower from 13,000 BC shows us that even the earliest of humans valued artistic expression. Expertly hung in a darkened room, these selections quickly transition us from Kusama’s glorious abstractions to a distant evolutionary lineage and New Zealand’s small place in that long chain.

“It makes no sense to consider humans as a special creation. Culture didn’t just come down from the skies and transform us. It does hark back to religious ideas of Genesis, that we are created by God in God’s image, or we are created by culture that can then ignore biology, it’s just very, very short-sighted, very parochial.”

With On the Origin of Art set up to accentuate the differences between the thinkers, it’s easy to overlook the commonalities that the curators share. The conflict hides their deep kinship. The common belief in evolutionary science as the foundation of artistic creation marks them as outsiders from mainstream academia.

“One of my spurs has been my hostility to the idea that everything is cultural difference in French literary theory and its wake, which seemed to deny the things that we share across humanity. I was very disturbed by the influence of French literary theory on the humanities in general in the 80s and 90s. Derrida and Foucault were so little interested in truth and serious argument. I wanted to come at it from a fresh angle.”

Boyd’s own interest in evolution stemmed from reading Stephen Jay Gould in the New York Review of Books, and intensified after reading his co-curator Steven Pinker’s The Language of Instinct and Simon Baron-Cohen’s Mindblindness. Boyd’s 1997 article “Jane, Meet Charles” was his first marriage of Austen and Darwin, of literature and evolution, and was the kindling for On the Origin of Stories – along with sharing the stage with Pinker at a panel on literature and science at the New Zealand International Festival of the Arts in Wellington in 2000.

Let’s take a brief side-tour of Steven Pinker’s exhibition. He has, alongside Boyd, the largest collection of art in the show, and some of the finest works. Sadly, either despite or because of his celebrity, he also seems least engaged with the task at hand. Where Boyd and Miller’s audioguides clearly drive towards a clear thesis, Pinker’s slipshod presentation (auditorily speaking) seems culled from a quick search of art-related writings in his previous works, but keeps returning to his main hypothesis that art is not an evolutionary adaptation. Interestingly, despite his disagreement with Boyd on this point, many of his selections would be equally at home in Boyd’s exhibition, such as Taiwanese artist Lin Jiun-Ting’s interactive Beyond the Frame which combines nature, pattern and play with four touch-sensitive screens that interact with four natural displays – falling leaves, blossoms, and so forth.

“Pinker’s view is that (evolutionary) adaptation is a rare and precious thing in biology and shouldn’t be appropriated where it’s not relevant. I think it’s very difficult to prove an adaptation or by-product hypothesis, frankly. We’re all still groping in the dark really. One of my key arguments is the one Richard Dawkins makes about beaver dams. If there’s no reason for these to be beneficial to the species, then beavers with no inclination to build dams would survive better than those who do, and the instinct would be bred out. And clearly it’s not, and it’s the same with humans and art.”

Boyd told me there were many items from Pinker’s exhibit he’d have “loved to snaffle”, but he’s done a spectacular job making do with his own selections. The next room continues Boyd’s deep dive into the past with an increased focus on the human, showcasing tribal masks from Mexico to Nigeria alongside contemporary considerations of facial patterning on one side of the room. Kiwi Marian Maguire’s lithograph Ko wai Koe depicts a cross-cultural interaction between a Maori man with moko patterning that mirrors carving on his counterpart, a Greek warrior, while Aboriginal artist Vernon Ah Kee’s haunting drawing Unwritten #8 sculpts a facial portrait from straight black lines that illustrate the unseen. Boyd suggests that the face itself is a pattern, and by extension these patterned faces are a bridge between cultures.

“Art across other cultures, even when we don’t understand a lot of the conventions, has an immediate appeal. We have so many affinities with one another, even with other animals. We had been told by Derrida that everything is language. Well, I’ve just had a hernia operation, there’s a lot that’s not language about the pain I gained there! Play is something that goes back, perhaps, 100 million years. It’s crucial to animals and it’s something that we feel fuzzy about - cat videos, and so on.”

This cross-cultural exploration of pattern continues in a side room. Here the woven work of Tongan, Auckland-based artist Sopolemalama Filipe Tohi takes pride of place. Paired with 14th century Egyptian doors, tiled Islamic pattern-work, and Native American basketry, it’s simultaneously a thesis statement for Boyd’s theory that interest in patterns can both transcend culture and exclude nature, as well as making an argument for the significance of Tohi’s work.

It’s interesting – but is it respectful? Standing amongst indigenous art and traditional headmasks that had been commandeered by white men to advance a theory, I couldn’t help but feel a moment of discomfort that again speaks to the dual nature of this exhibition. While this work is treated with aesthetic reverence, would its creators be comfortable with their work being used to advance a theory many may disagree with? Boyd, for his part, had spoken to very few of the artists featured (one notable exception: Fiona Pardington, with whom he’s collaborating on an upcoming work involving Nabokov’s butterfly collection), to say nothing of those who couldn’t speak for themselves. Certainly the 14th century Italian painter Jacopo di Cione would be bemused to have his painting of the Madonna commandeered by forces that discredit the notion of anything spiritual in art.*

The agora that MONA has created may be as equally hostile to the spiritual as the theories it seeks to supplant, but Boyd considers himself warmer to religion than most.

“If anything, my work in evolution has made me more appreciative of the role of religion in human life. Religions have had evolutionary advantages … they do encourage social cooperation, and the fact that they’re probably not factually correct is less important than the motivation that they provide to cooperate with each other.”

As I entered the next room of Boyd’s exhibition, with Kiwi artist and filmmaker Len Lye’s animations taking pride of place, I wondered whether representing Aotearoa was an intentional element of his curatorial mission. Boyd reveals that “it crept up on me gradually, I came to quite cherish the fact that I did have good New Zealand and Pasifika representation, but it wasn’t a major motive from the start.” While unintentional, it’s a pleasure, as artists from Aotearoa are otherwise poorly represented in On the Origin of Art, with the notable exception of Kiwi-born video artist Daniel Crooks, who is featured in Mark Changizi’s exhibition. Crooks’ visually elongated tai chi abstraction, Static No. 12 (seek stillness in movement), is a highlight of the entire show, and with its transformation of movement into geometric pattern, arguably equally suitable for Boyd’s exhibition.

Theoretical neurobiologist Mark Changizi is the outsider on many fronts; he’s the only thinker not mentioned in Boyd’s book, he admits in the catalogue that his work about humans as “nature-harnessing” has focused more on the evolution of alphabets, his curation seems heavy on recent commissions, and his relatively small selection is very focused on work that explicitly mimics or relates to the organic. This also means that many of the pieces err towards the decidedly disgusting, which is perhaps to your taste more than mine. However, despite these limitations, its highlights cannot be ignored, both in scale – American sculptor Aaron Curry’s Daft Dank Space consumes the entry with its giant unwieldy psychedelic space – and sheer joy, in the case of a giant cylindrical interactive piece by London-based art practice studio United Visual Artists that generates responsive light patterns to user movement. Play with pattern: sound familiar?

While this and other works chosen by Changizi would have fit well with Boyd’s theory, there is an internal logic to Boyd’s work that would resist the disruption that adding these works would create. “I picked the works very quickly … I had a clear sense of the rooms, and how they follow each other.”

Having visited in the end of 2016, it’s almost needless to say that current affairs loomed large in my mind, and left me mulling on an unrelated question: can art get us out of our present muddles?

And so, over the course of the next few rooms, Len Lye and Dr. Seuss spill into environmental sculptor Andy Goldsworthy, into Aboriginal painter Kathleen Petyarre, as Boyd unfolds his theory (if you’re listening to the audio guide), moving from examples of play with pattern for play’s sake to the use of pattern for social cohesion, as in the colourful garb and buildings of the Ndebele people. At times, the whiplash between high and low art is extreme, particularly when an OK Go video is next to interactive displays of Shakespeare’s sonnets that call attention to linguistic patterning. It’s a curious side effect of curating towards a thesis that’s universal, showcasing cognitive play with pattern. Making a case for its ubiquity almost by definition requires showcasing work, like a Gotye video or Keith Haring painting, that might otherwise be considered too gauche for a high art setting.

Having visited in the end of 2016, it’s almost needless to say that current affairs loomed large in my mind, and left me mulling on an unrelated question: can art get us out of our present muddles? Two key rooms near the end return the focus to contemporary art, merging patterns of the past and present with compelling results. Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed’s extraordinary Liquid transforms traditional rug-making into a melting puddle, while Moroccan-born Mounir Fatmi’s video projection Modern Times creates a Chaplin-esque churn from traditional Arabic symbols. Meanwhile, a room dedicated to the work of American comic book artist Art Spiegelman showcases one of the few art forms entirely generated in the 20th century. It’s a summatory argument for Boyd’s theory of art as adaptation, and for me, a compelling one.

But is this evolutionary urge to create and develop patterns still of utility in a time where we are surrounded by so many patterns? Thoughts of fake news, algorithms designed to shape our thoughts, and conspiracy theories circled in my head as I entered the final room of the exhibition.

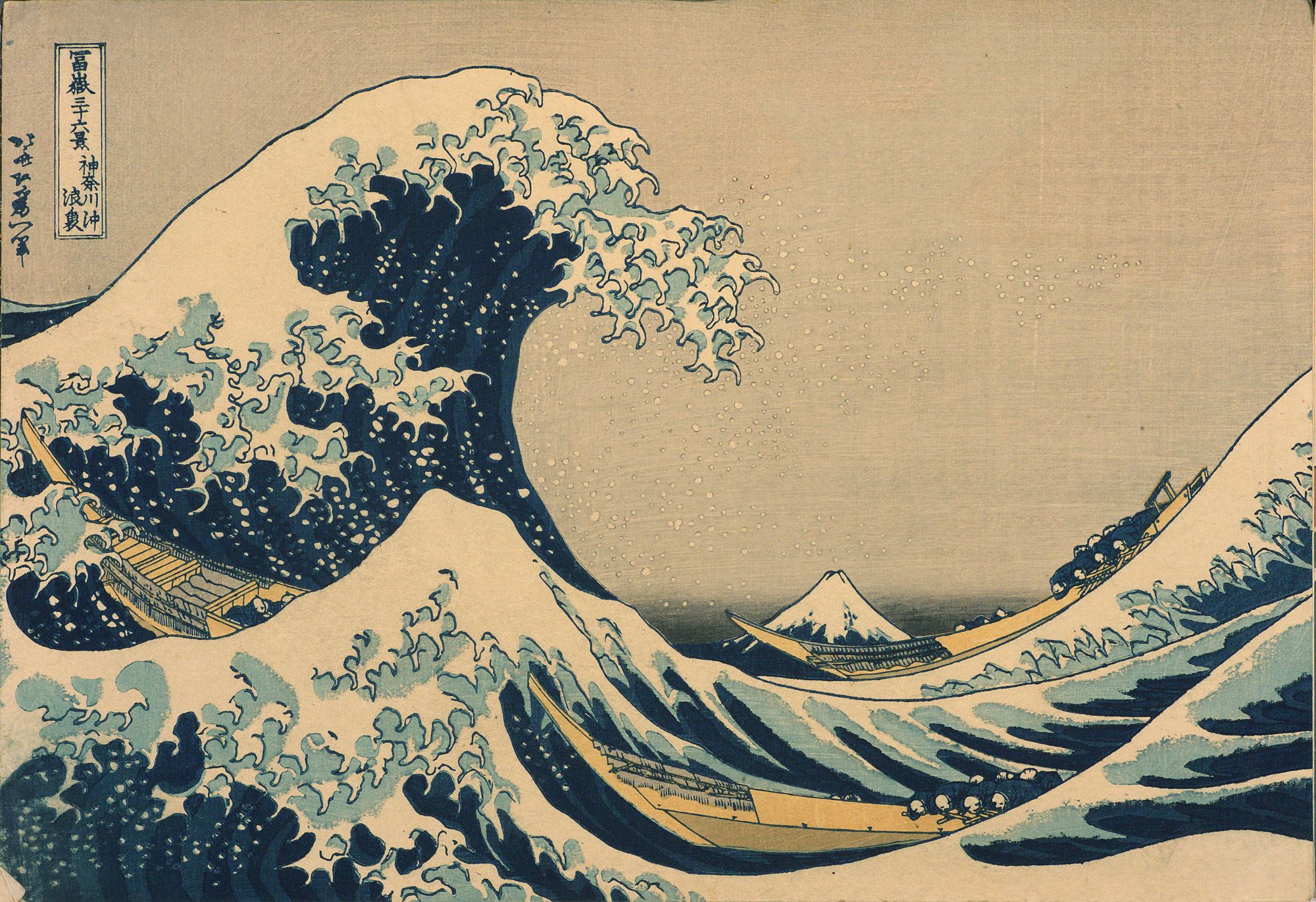

Boyd closes his exhibition with legendary Japanese artist Hokusai’s 19th century woodblock print Great Wave off Kanagawa. It stands alone in a small dark room, and left me on a slightly funereal note, reflecting on the great waves taking place in the world, and wondering what significance this discussion could possibly have in the larger world. When I shared this thought with Boyd, he put aside his differences to agree with Steven Pinker and his book The Better Angels of Our Nature, where Pinker argues violence is declining both in the short and long run.

“One of the interesting things about evolution is that people think it ties us to the past, but it’s about change, and one of the amazing changes we’ve got to now is that cultures are no longer isolated and jammed up against each other ... in the past the natural result of two cultures meeting is that one would annihilate the other. In places like France, that’s how it became a nation. There’s whole populations that were wiped out. That doesn’t happen as a norm anymore, and we’re rapidly adjusting to the value of multiple perspectives. We’ve had a few setbacks this year, but I’m still optimistic about the long term.”

Whether or not you share Boyd’s optimism – or even his worldview – On the Origin of Art is a rare and powerful show, one that justifies a trip across the Tasman and that will linger in your brain long after your visit in ways art exhibitions rarely can.

*Editor's note: After publication, Boyd contacted the author to clarify this point, saying: I didn’t speak to most of the artists because they’ve been dead for decades, centuries or millennia, but I did indeed speak to Filipe Tohi (and wouldn’t have selected so much of his work had I not done so and thereby learned more about his art), to the other New Zealanders, Fiona Pardington and Marian Maguire, to Art Spiegelman in New York, Rob Kesseler (the photographer of the pollen photos) in London, and to François Morellet in his studio in France. I would have loved to speak with Yayoi Kusama, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Mounir Fatmi had it been possible to see them. As for respect for artists from other traditions: I spoke to Rose Mahi, a direct descendant of the Hawkes’ Bay leader, Takimoana Karaitiana, who commissioned the poupou; Rose was so thrilled at their inclusion in my part of the show, she couldn’t stop laying her hands on the carvings of her ancestors, and pointing out what each feature meant. With Fiona Pardington (Ngai Tahu, Kati Mamoe and Ngati Kahungunu) I attended a welcome by the local aboriginal people to the Maori artefacts being brought to the show, which was also a celebration and explanation of the Aboriginal works in Steven Pinker’s and my parts of the show. The Ghanaian-born philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, marvellously, that we approach art “not through identity but despite difference. We can respond to art that is not ours; indeed, we can only fully respond to ‘our’ art if we move beyond thinking of it as ours and start to respond to it as art. . . My people—human beings—made the Great Wall of China, the Sistine Chapel, the Chrysler Building; these things were made by creatures like me, through the exercise of skill and imagination.” I think Pueblo or Aboriginal basket-weavers would be thrilled that people far from them in time and place and social space admire their art as proof of what humans can achieve.