The Sea Brought You Here and Now You Must Go Back: A Review of Namesake

What does a name really hold? Hana Pera Aoake considers Quishile Charan and Salome Ofa Tanuvasa’s recent exhibition at Enjoy Public Art Gallery

What does a name really hold? Hana Pera Aoake considers Quishile Charan and Salome Ofa Tanuvasa’s recent exhibition at Enjoy Public Art Gallery

“Somewhere between conception

The womb

The birth

Knowledge was transferred

The memories are still alive

They sing: do not forget us”

Names tell a narrative, as a means to carry the memories of our tupuna. These might get lost or be displaced or forgotten but these memories are seeped into our bones. The weight of colonialism and our continual survival is embedded within our names.

I often think about where my own name comes from, Hana Pera. Hana comes from Koroneihana or coronation and Pera was my late Kuia’s name. I am named after my Kuia, a woman from Ngāti Mahuta, who died before I ever met her. Her namesake was her father Raihe Ngapera Kaweroa or perhaps my great-great-great Koru Ngapera Naeroa, whose land was confiscated in 1900. There’s this sense of mourning that I’ve always felt in my bones at having never been able to have met her. I think it’s the reason I feel such an affinity for Kawakawa. It is a plant often used during tangihanga, as well as marking the passing of a loved one. It’s the smell, as well as its colour that always reminds me of the taonga I was given.

Namesakeby Quishile Charan and Salome Ofa Tanuvasa was an exhibition on at Enjoy Public Art Gallery in Te Whanganui-a-tara, Aotearoa (29 June–22 July 2017). Both artists made work which focused upon their love and respect for the matriarchs within their families. Salome focuses upon her Mother, whereas Quishile focuses upon her Aaji or paternal grandmother. Both take their names from their grandmothers, with their work being drawn together through their shared acknowledgement of where they have come from and the significance of carrying the names of their ancestors before them. This exhibition came together through friendship and an exploration of their individual relationships to their lineage, diaspora and memory. The exhibition was accompanied by a publication titled The sea brought you here, which features generous writing, photographs and illustrations by both artists, as well as texts by Hanahiva Rose and Sophie Davis.

The artist continues in the tradition of textile making like her Aaji and in her practice continues to acknowledge the bodies of knowledge passed down to her and the legacy of colonialism.

The works by Quishile made for Namesake are small in scale and combine a range of different techniques, including embroidery, screen printing and laser cutting. These are the most intimate works by Quishile that I’ve seen. Other works including, Salty tears and sugarcane fields (2016) at Artspace and Temporary Vanua (2016) currently on display at The Adam Art Gallery are enormous. Quishile’s Aaji first introduced her to textiles, and for Charan represent the physical embodiment of her Aaji, charting the history of her tupuna’s indentured labour.

The first work in Namesake is a suspended cloth made of natural cotton and dyed using Kawakawa by Quishile with the words Before I loved my gods. I loved you. Hung on plywood it is fastened to the ceiling via rope. This is the first time Quishile used Kawakawa, in the past she has used other natural ingredients like Haldi (Turmeric), vegetables and clay on natural fibres like cotton. I was only recently told that Kawakawa was used by Māori in mourning ceremonies. I had primarily known of it being used for Rongoā or medicinal purposes, namingly tooth aches, bruising, stomach pain and anxiety relief. Pare Kawakawa (head wreaths) was and is still sometimes used during Tangihanga (Māori funerals) and also where to mark the death of a loved one. The Kawakawa gives Quishile’s work an off green colour that isn’t consistent, staining it in speckles of a dark green that looks almost black, with threads dangling at its ends. The smell of this work wafts through the gallery and on the back, is a text outlining the origin of Quishile’s name. Quishile’s first name is her Aaji’s name, which is ‘Shile’. Her last name ‘Charan’ was split by the British when her ancestors were taken from India and forced to work harsh labour in Fiji. Last names are a western concept. At the ports the British split the first names, as a means to enforce control. To carry someone’s name is to carry the weight of their memory. The artist continues in the tradition of textile making like her Aaji and in her practice continues to acknowledge the bodies of knowledge passed down to her and the legacy of colonialism.

This focus on maternal histories is manifested visually through references to domesticity, which is constantly reiterated throughout the space. Three other textile works are hung to the right on a makeshift clothesline, hung on two pegs. At the edges of each are beaded shells. Arranged like a triptych, a laser print of Quishile’s Aaji is in the centre and is flanked by embroidered Hibiscus flowers and dalo. The image of her Aaji is from the 1990s and features a Sari that is now owned by the artist. Quishile has inherited a number of Saris from her family and when she wears a Sari she is physically embodying them. The redness of the flower acts as a reminder of Fiji and serves as a physical embodiment of flora memories of home. Her Aaji grows hibiscus in her garden and they also act as an offering during prayer (puja). The embroidery of a dalo is an ode to Quishile’s favourite meal with dalo called rourou, which for Quishile is both a representation of Fiji and reminiscent of memories of home. Dangling on the edges adorning these smaller textile works are lines of hand sewn shells. The adornment of the work with Quishile’s Aaji has longer strands of these at the bottom, with red and yellow beading also threaded. The two either side of it have the tops also adorned in shells, but are folded over the clothesline and are visible through the cloth.

What does it smell like and what does the wind sound like?

Charan’s work reclaims traditional knowledge systems. Her textiles are visual narratives that mediate a grieving and healing process, whether this be through sharing cultural or familial histories or meeting and connecting within these communities. These works contemplate the legacy of displaced colonial shame around indentured labour within her community. It seeks to have difficult conversations in a way that enables a gentleness and a safety.

Did you know that the Pacific is not just a body of water with some islands scattered across it? It’s a Wheke, it’s all connected as one body.

“The sea brought you here and now you must go back. Your sea calls you and I see your heart and eyes. You speak of home in your daily tongue.”

The lines drawn on the wall by Salome Tanuvasa in Namesake made me think of my ancestors thousands of years ago travelling from Taiwan and spreading throughout the Pacific following the stars like the Ocean’s wave. It still seems so unbelievable to me that we travelled so far from South America across Micronesia and South-East asia to Aotearoa in double hulled canoes. I thought of the way I talk to my whānau now through long distance phone calls across bodies of sea or via facetime through the internet, which is tiny cables embedded on the seafloor.

Salome’s name, like Quishile’s carries the lineage of her whānau. Her first name Salome comes from her maternal grandmother who lived in Vava’u, Tonga, while, her middle name, Ofa comes from her paternal grandmother who lived in Nofoali’i, Samoa. Her work draws on her relationship with her Mother and the connections she has to home. The lines both refer to the Ocean and perhaps the many miles her mother travelled as a young woman across the Pacific to Aotearoa in the 1970s searching for opportunities for herself and her whānau. It would not make sense if the lines were straight, the lines are rounded and surging up and down. These lines look like waves or radio lines, this kind of movement seems to refer to the relationship between digital and physical space. The lines recall phone cords, like tentacles reaching across oceans from here to there.

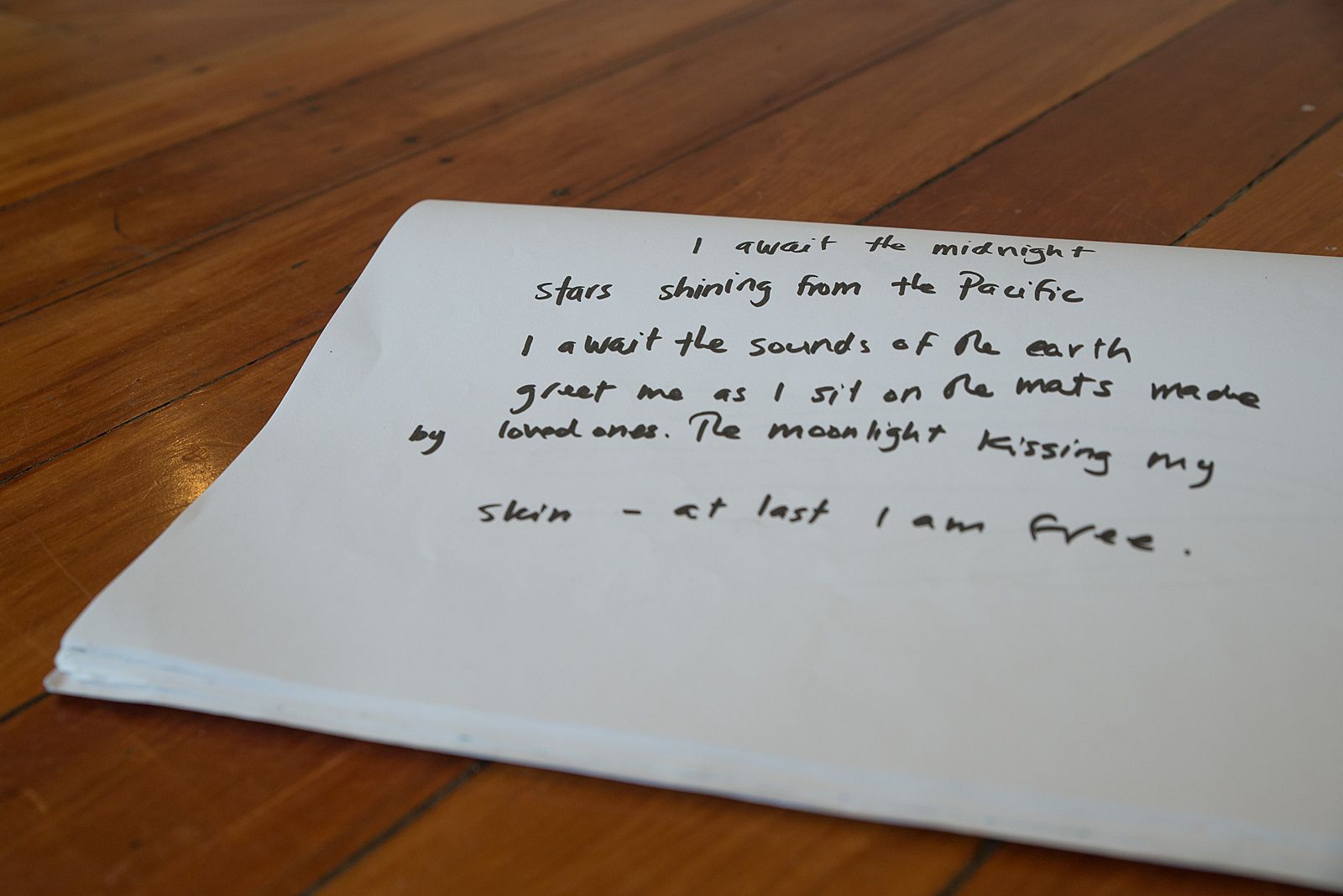

Salome’s starting point was her mother’s phone book. Numbers of whānau were written into a regular exercise book. Salome began drawing in a sketchbook, as well as asking her Mother questions about Tonga. What does it smell like and what does the wind sound like? Through these questions Salome is clearly trying to connect and understand her relationship to place and the reality of living in diaspora. This resulted in Salome presenting a sketchbook, which was placed on the ground, with words and drawings by the artist and her children. On the wall is a video work with shots of Salome’s view from her kitchen window in the morning and of her mother’s kitchen window view at dusk. Plants flap in the wind. Again, the quiet intimacy of these shots reflects on domestic spaces and on maternal connections to space. There is a nice visual relationship between the cord winding down from the screen and the wave lines Salome has drawn on the wall.

This exhibition in many ways forced me to reflect upon my own relationship to place, my own name and the history of my own whakapapa, which I continue to learn and understand more about. I thought a lot about the long line of women in my family and how they are a part of my mauri guiding me from Hawaiki, after passing through Te Ara Wairua[1] long before me.

The idea that colonialism is somehow over is ridiculous, because these histories are passed down whether it’s intentional or not. These histories appear in our names and anchor us back to our families and their journeys whether this is across oceans or just trying to find ways to survive. The fact that they did survive waves of colonisation empowers us through our names to continue to find strength in reclaiming our narratives outside of a western gaze through collectivity.

This exhibition caused me to reflect also upon the importance of my own collaborations. When you live away from home and from whānau, you must draw upon other people who can uplift and support you. In an art world and market so heavily burdened by capitalism and Western hegemonies, finding these support networks is crucial but can be difficult when you aren’t Pākehā. In art education, individualism is deeply engrained within these colonial frameworks, while collaboration is often seen as being harder to disseminate, without demarcating the roles of each collaborator. In a non-western context, art making or rather creating rejects authorship, as it rejects ideas around ownership and possession. This is especially the case in the context of textiles, which is a collective activity of learning and making. While their practices may be very disparate from each other, I am very much looking forward to seeing further collaborations from Salome and Quishile in the near future.

29 June 2017 – 22 July 2017

All images courtesy of the artists and Enjoy Public Art Gallery

[1] For Māori Te Ara Wairua is the pathway that the spirits take via a Pōhutakawa tree towards Hawaiki. This pathway is located at Te Rēinga Wairua or Cape Rēinga at the top of Te Ika-a-Māui (North island).