Chalk Stories: A Review of My Best Dead Friend

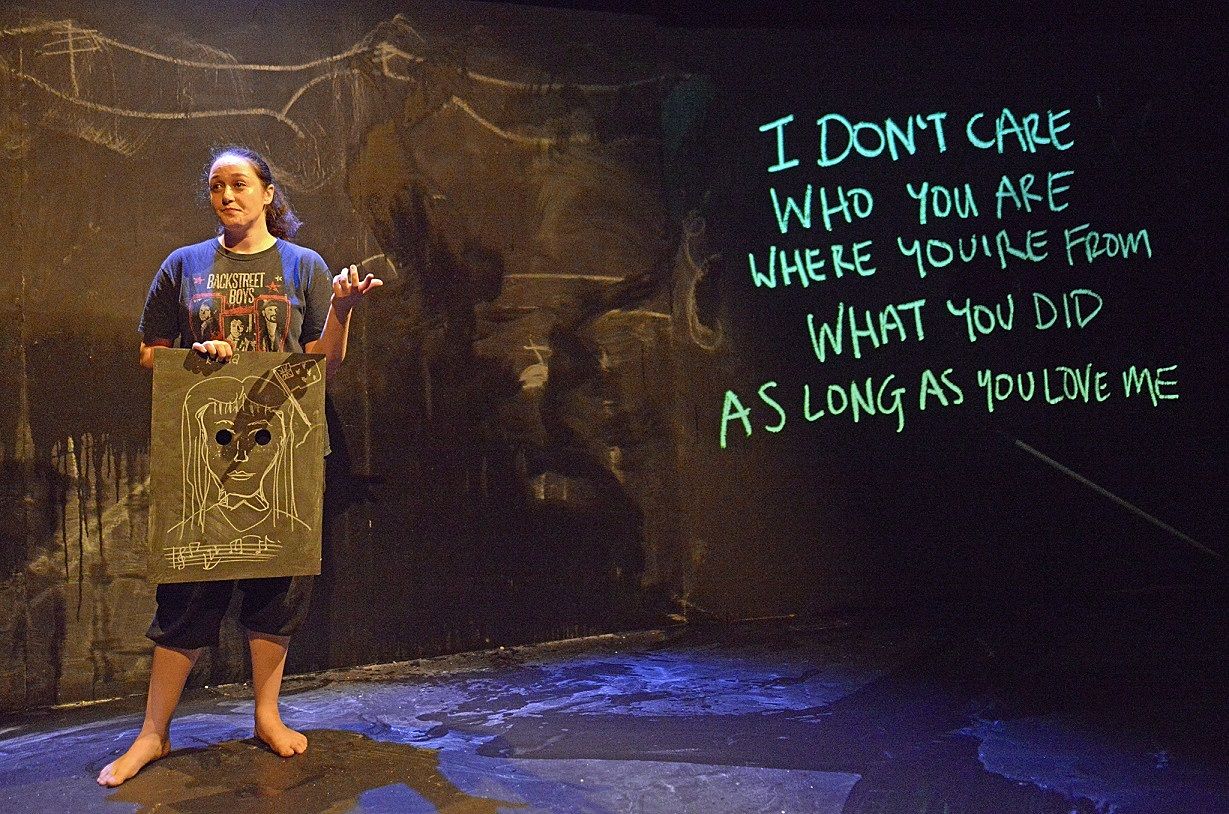

Anya Tate-Manning draws on personal stories of loss, finding your place, and the Backstreet Boys in 'My Best Dead Friend'.

Anya Tate-Manning draws on personal stories of loss, finding your place, and the Backstreet Boys in My Best Dead Friend. Big topics, and as Melissa Laing discovers, they're treated with a remarkably deft touch.

We all have holes in our life left by people who are gone – be it overseas (without us) or gone gone. Dead. We skirt around these holes and sometimes fall into them through our grief and loss. We talk about the absent people who filled them to others, if they will listen. If we’re artists, like Anya Tate-Manning, we make works that buttonhole willing audiences so we can tell funny stories edged with loss as a way of processing our (shared) grief. My Best Dead Friend is a story about grief. A light-hearted joy-filled telling of how five young people became interwoven in each other’s lives as friends and co-conspirators and what happened when their lynchpin, Ali, died. It’s set in Dunedin in 1998 and 2012, but it’s also set right now, in the theatre, around the edges of the hole Ali left.

Anya is playing herself. She’s not ‘acting’ per se, and that’s possibly the first thing you notice as she comes onstage without ceremony, dressed like her awkward seventeen-year-old self: cargo pants, Backstreet Boys T-shirt, pony-tail. She’s here to tell us a story as if we’re sitting with her on the sofa late at night and she needs us to understand why she’s struggling at the moment. The story starts with her oldest friends. They’re seventeen going on eighteen, recently freed from high school, and filled with both the potentiality of the future and the edgy discontent of not yet being on their way to it. They’re five friends who found their tribe at school – the weird ones – and formed a tight-knit circle to survive small-city life where the Saturday night social events revolve around sport and driving around the Octagon repeatedly and god help you if you're smart or creative.

Like all tribes, the friends each have their designated roles. There’s the bossy one, the cleverest one, an Australian one, the one whose generosity envelopes the group, and Anya, the geeky fangirl who can spin off all the trivia about Backstreet Boys – and hilariously does so in the show’s opening third. The act of positioning herself against her friends in a self-deprecating way is one of the humorous pivots of the show. They're literary, political, risk-taking and confident; she's pop-culture obsessed and cowardly. They’re reading Marx; she’s watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer. But nonetheless, when they all go out one night to incite workers to overthrow the capitalist structures of the world with chalked poetry, she’s along for the ride. It’s a failed action they never speak of afterwards, but it unites them.

Chalking becomes not just the method of revolutionary action in the story but an integral visual device in the work which carries the narrative forward. The set is deceptively simple; a slightly curved blackboard wall, tinged grey by washed-away chalk and five smaller, removable blackboards that are drawn on over the course of the play. The design by Meg Rollandi and the integration of the chalk drawings into the story is inspired and gives Anya a device to play against so that she is not left to hold our attention with her words alone through the full 50 minutes. Anya’s cargo pockets are filled with white chalk and she hands these out with the blackboards as she invites audience members to interpret her descriptions of Emma, Dougal, Tessa and Ali. Working from Anya’s verbal sketches, we speckle faces with freckles and add glasses, frown lines, flags and prominent noses to the drawings with the result that each friend is easily distinguishable from the others. These endearingly amateur drawings of faces help us keep track of the key characters throughout. As the story progresses, the hills, streets and phone lines of Dunedin slowly fill, and are subsequently erased from the blackboard. Literary luminaries names are dashed out on the floor and then washed away.

Working from Anya’s verbal sketches, we speckle faces with freckles and add glasses, frown lines, flags and prominent noses to the drawings.

The tension between literature and popular culture through the play underpins the work’s exploration of the experience of growing up in New Zealand at odds with the dominant culture. How and with whom do we find a space in the world to be ourselves? The pivotal gesture of Anya and her friend’s creative rebellion, inspired by New Zealand poets, illuminates the constant struggle for a complex, diverse and nuanced cultural identity, where the arts are not undervalued; a struggle that begins at high school. The chalking is a gesture that speaks to passion, outrage and – at 17 – the burning need to find some way to intervene in what is wrong in the world. But the biting irony is that the only text that remains with light of day belongs to a boy band who, Anya tells us, now perform daily on a cruise ship unable to escape their fans. The futility of the chalking underscores the naivety of the belief that a single transformative encounter with poetry could change the world. That’s not simply a youthful idealism either – the transformative power of art is a notion that many of us hold dear, it’s simply that in our adulthood, we modulate it with the recognition that while the arts touch us personally they will not achieve structural change on their own. The transience of the chalk – washed away in real life by the hidden infrastructure of the city and by Anya in the play as a means of transitioning from the optimism of activism to Ali’s abrupt death – becomes a metaphor for the fragile transience of our lives and our efforts.

Anya keeps the theatre in a ripple of laughter throughout My Best Dead Friend, treading lightly over the grief that Ali’s death caused. But the looming death, the details of which are not revealed until the last third of the play, focuses our attention on the unadorned tale of being young, restless and ready to change the world (or at least change the people of Dunedin). Throughout the play the gravity of Anya’s loss lends significance to a single evening whose events were swiftly passed over and deliberately forgotten.

Despite the conscious embrace of humour to tell her story, we should not doubt the depths of Anya’s grief. As she comes to the funeral she struggles to hold back her tears. Even though the trauma of Ali’s death is emotionally specific to Anya and her friends, the story My Best Dead Friend tells is a universal one and I believe we will all find a point of connection within it. That may be in the process of making a space for yourself in a world that isn’t quite right and the joy of discovering that there are people out there who share your feelings, or the negotiation of the holes people have left in our lives as they depart. My Best Dead Friend tackles big subjects with a light touch. Its deceptively simple, clever and well worth seeing.

My Best Dead Friend runs from July 12-22 at Q Theatre. Tickets available here.