Triple-Inception: A Review of Lick My Past

Jess Bates revels in the joyous subversions of Nancy Wijohn and Kelly Nash's new contemporary dance work, Lick My Past.

Jess Bates revels in the joyous subversions of Nancy Wijohn and Kelly Nash's new contemporary dance work, Lick My Past.

With Tāmaki Mākaurau now in the height of the Māori New Year, the Basement’s Matariki Season programming is offering up a multi-disciplinary smorgasbord of what might be called ‘culturally’ curated work. The idea of grouping work by this definition is more than a little hairy, but the diversity of the line-up speaks to that complexity. Dance-theatre work Lick My Past sits alongside contemporary sound work Poropiti; Mo and Jess Kill Susie is served up entirely in te reo; there’s even a Māori musical. Matariki Festival has its roots in the Māori Language Commission’s 2001 move to regenerate Te Reo by reclaiming the Māori New Year; it is everywhere now, from the Observatory to star-weaving in Kohanga curricula, and that raises some interesting questions about how state recognition determines and codes culture, and indeed, who is watching. I cannot presume to say how these questions have impacted the makers of Lick My Past; only to say that at the core of this work lies an unyielding interrogation of the audience’s gaze.

Lick My Past is a rare contemporary duet between two titans of contemporary dance: Kelly Nash and Nancy Wijohn are highly-regarded for their work inside dance company Atamira. Nash and Wijohn identify as Māori/Pākehā performers and this collaboration is a self-declared reflection on their “long” and “stressful” dance careers. The title of the work (which I love) flexes both a queer and indigenous boundary, inviting the audience to both be titillated by, and to arouse, Nash and Wijohn’s “past”. As a Pākehā reviewer, there is a long-standing power dynamic of artistic definition present as I watch and as I write. Similarly, institutional celebrations of Māori work set up an infrastructure designed to make indigeneity ‘legible’ to a Pākehā framework. This adds no small degree of context for Lick My Past.

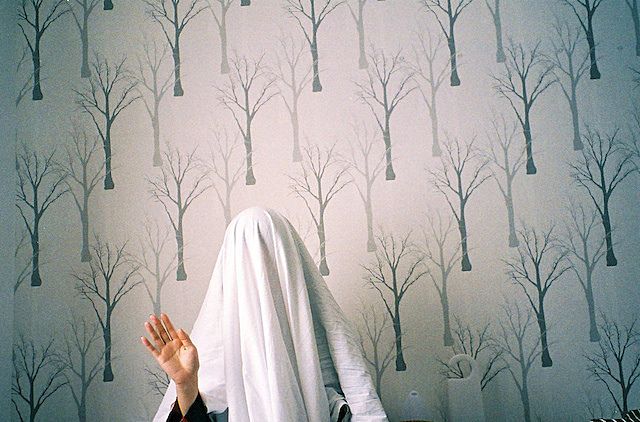

You are looking at me; I am looking at you looking at me; you are looking at me looking at you looking at me.

From the moment Lick My Past opens, to the soaring strings of our classical canon - Beethoven’s Egmont Overture – Nash and Wijohn play with our silent ‘cultural’ expectations. The music couldn’t be more ‘continental’ if it tried, but Nash and Wijohn pair this reverent soundtrack with banal movement. They run in increasingly large circles, gesture heroically, and tyre-run as though in a crossfit studio. These two experienced, highly-skilled dancers refuse to choreographically deliver on the gravitas their faces convey, and the result is both audience and artist laughing at their own latent desires for Māori consumption and production. This is in no small part because this work sings to Nash and Wijohn’s own long-suffering dance community, a discipline with a limited audience, few opportunities for employment and a perpetual demand for virtuosic movement. The opening night crowd guffaws with knowing laughter at the ironies and in-jokes of two highly-skilled dancers refusing to choreographically deliver on the gravitas their faces convey. They bring a knowing wink into the work with their proud demonstrations - “mummy, look at my trick!” - as they forward roll and grin like clowns who study gymnastics part-time on a Tuesday night. A lovely inception of triple audience acknowledgement is at play: you are looking at me; I am looking at you looking at me; you are looking at me looking at you looking at me.

Their fierce performativity, bordering on clown, defines their relationship. They covet audience attention like students in a high-school pantomime: Wijohn is the scene-stealing hero, every particle of her demanding to be watched, and Nash the focussed and earnest co-performer, furiously side-eyeing her partner in competition and in supervision. They meet a series of dramatic and powerful climaxes in the Overture with a set of tableaux, contorting their faces to the heights of emotion: terror and delight and bad Titanic lifts. As the light pops up to stylise their frozen expressions, the tone has been set: dance-parody will be pushed to its limits tonight.

Parody makes us aware of our act-of-watching and, in so doing, can poke fun at us and our culturally-ordered desires and expectations. As Lick My Past continues, this reflection is made literal. Two square mirrors obscure the dancers’ upper bodies, creating leggy floor symmetries, and reflecting back to us our own projected fascination. This is most delightful as a four-legged abstraction, like a pair of human insects, seducing us with their bare temptations, but is less interesting when used in other formulations as a mirror-headed woman. By contrast, Wijohn’s later balloon solo builds with precision. As she bats the balloon around the stage, dreamy and childlike, to a sweet indie soundtrack, it recalls the naive world of ‘magic’ conjured up in any number of telecommunications advertisements. Moments later, balloon-up-shirt, she contemplates the comedic futurity of a bulbous pregnancy. Wijohn’s sassy, po-faced commitment to every moment is undeniably captivating. She exists on stage in a hard, challenging way, penetrating the audience with her amplified, challenging gaze. I could watch her stalk around the stage in hi-femme transition mode, moving props like a ring girl, for a good few more hours.

If Matariki is all about tuning in to hear the Māori story, then Lick My Past is like a wet willy in our ears.

This playful erotic quality of invitation and refusal infuses much of Lick My Past. When the room begins to glitter with Rowan Pierce’s mirror-ball projections, as much Stardome as ballroom, Nash and Wijohn’s faces become masks of gauzy sexuality set to The Drifters’ Magic Moment. It feels for a moment as if this is their wedding dance. The peep-show continues when they reveal a wall of breast-plates underneath the curtain – but we are permitted only a moment’s glance. At the height of the absurdity, Nash enters with the long points of a crescent moon protruding from her forehead and chin - a costume that is simultaneously rich with sexual potential and awkwardness, like a nun with pincers. The show dissolves into more genuine connection in its later moments where the two bodies lie side by side in an intimate duet, stargazing in the purple light.

When the balloon finally pops later in Wijohn’s solo, she irreverently uses its carcass as chewing gum, its own kind of Kylie Mole funeral. And when she spits it out? It reads like white flesh on the black wall of the theatre: like a chewed-and-spat galaxy, which could serve as an uncensored retelling of the Matariki myth.

Lick my Past is a bold metaphor for the contemporary continuity of the sexualised colonial gaze. It’s probably useful to note here that these two performers are in a relationship, because it plays into the very temptation of the title. The performance itself transmutes this instruction into a rude gesture by refusing our desire to really ‘know’ them - whether their virtuosic skill, their intimacies, or their Māori whakapapa. If Matariki is all about tuning in to hear the Māori story, then Lick My Past is like a wet willy in our ears. The (invariably Pākehā) act of listening is most clearly subverted when they take turns eliciting stories from different parts of each others’ bodies. We hear of shoulder injuries, “right side privilege” and the meaning of the “third eye”. This micro-storytelling is done with all the booming, obtuse rhetoric of a spoken word poem – but just as we might learn something, the contact breaks and the story is clipped off. Our potential gratification from ‘knowing’ is always held at bay. Its function is made abundantly clear when Nash places her hand at the small of Wijohn’s back, which initiates the ceremonious opening of a tale beginning “my whakapapa spine.” The audience is in stitches.

Every stereotype of Matariki programming slaps us square in the face, and we are forced to giggle at our dumb cultural expectations of Māori work.

We never get to hear the mythology of that spine, this moment instead flagging exactly the kind of institutional wet dream that festivals like this are often more than willing to encourage. Every stereotype of Matariki programming slaps us square in the face, and we are forced to giggle at our dumb cultural expectations of Māori work. This moment is Lick My Past’s self-authorisation, a refusal, guns out, to adhere to the basic stereotypes of indigenous arts that CNZ funding pools authorise. Nash and Wijohn can play that game if they want to. But they don’t: just as they offer this idea, they collapse it, deftly moving between vocal qualities. Their body narratives code-switch from trauma to pride, from the high-pitched melodrama of a child recounting their fall, to the jaded and earthy conviction of a vagina monologue. The overwhelming sense of never-knowing appears a lot more “Kiss My Arse” than Lick My Past.

The real magic of this show is its unashamed delight at being made - as Wijohn lovingly bourrées off the stage cradling that nun-pincered headdress, she takes great joy in being watched. Every prop is treated with a sense of deeply silly ritual and Nash and Wijohn clearly relish the chance to perform with one another, with corpsing smiles and knowing glances aplenty. As a non-dancer, I cannot speak choreographically to the work, but nor do I need to. The quality bubbling beneath Lick My Past is universal - we can all recognise pleasure. It oozes from every pore of the artists on stage - they are grounded and flippant and pleased to be here. It’s a lesson in performative joy: simple, clever and deeply hilarious.

Lick My Past runs from June 27-July 1 at The Basement Theatre.

For more information about Lick My Past, go here.