Trauma, Consensus and Romantic Comedies: A Conversational Review of Jane Doe

Kate Prior and Rosabel Tan discuss Eleanor Bishop’s Jane Doe, which is currently playing at Q Theatre before travelling to the Edinburgh Festival in August.

“I moved from New Zealand to the United States in 2013,” writes writer and director Eleanor Bishop in the notes to her show, Jane Doe, “around the time that the issue of sexual assault on college campuses was exploding.” From this experience came a complex show that presents, with deceiving simplicity, all the elements of daily life that shape rape culture.

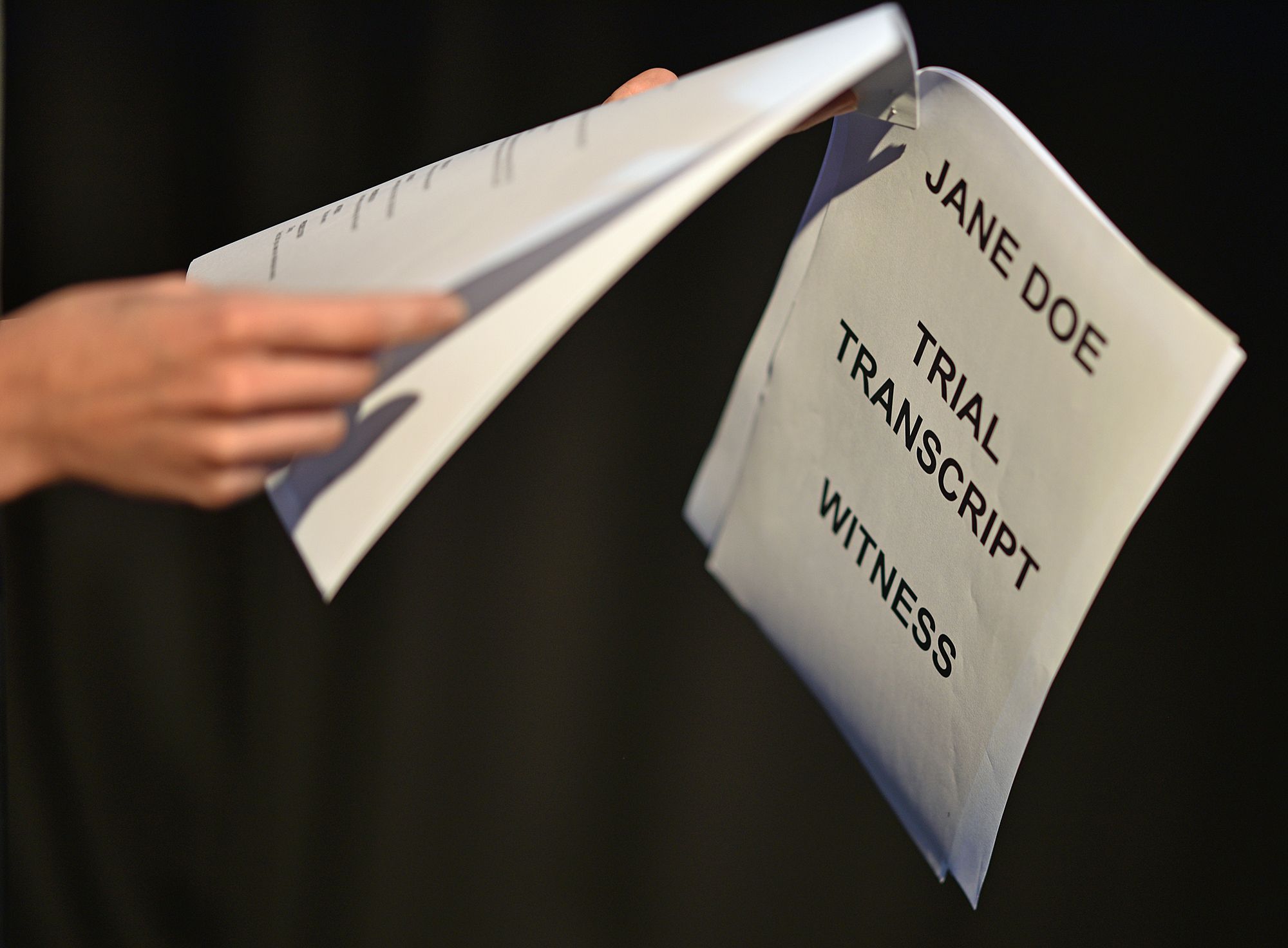

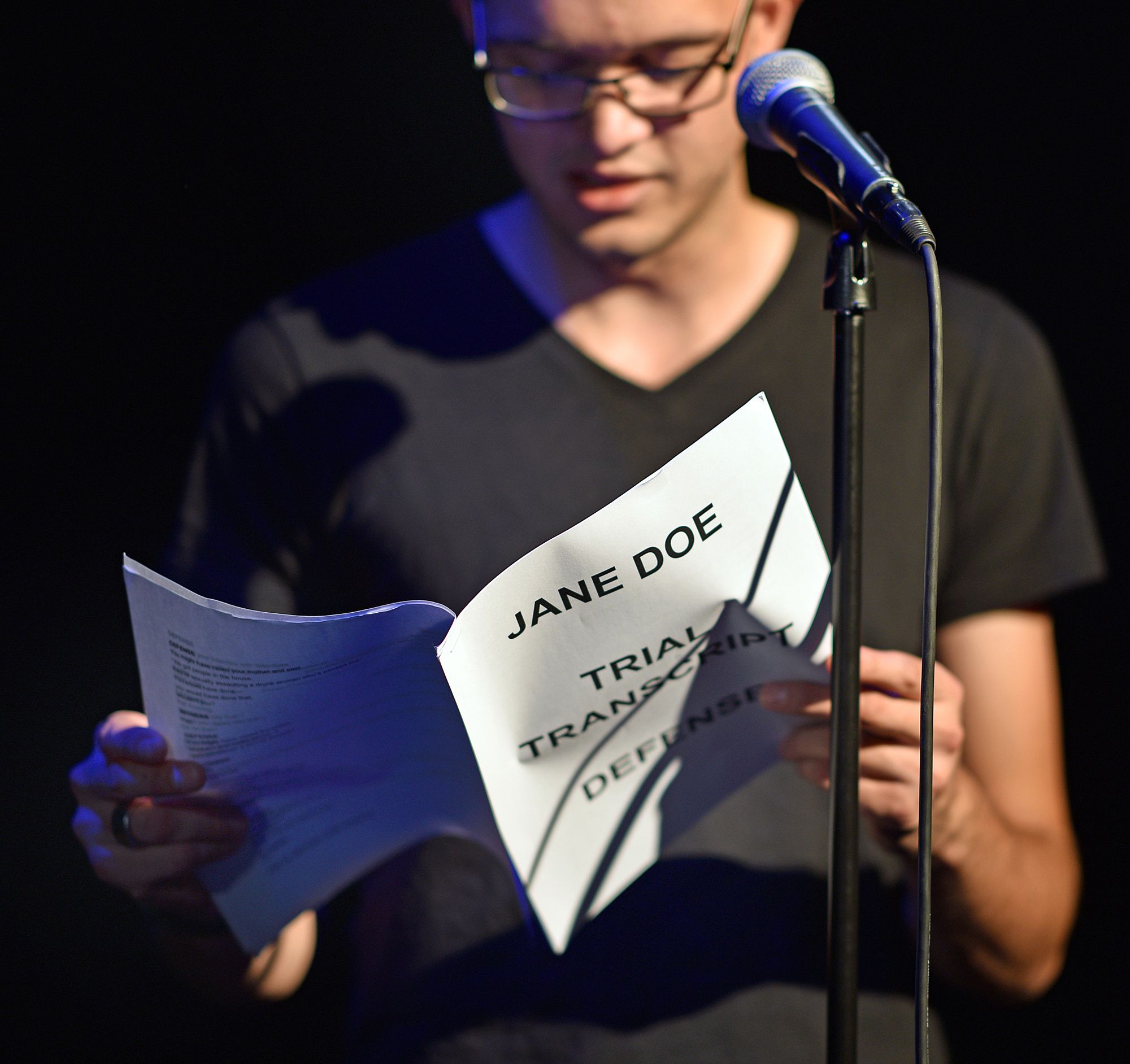

There are several threads to the work. One is a storytelling thread, which consists of performer Karin McCracken telling stories of a sexual awakening via romantic comedies and first loves. The second is text inspired by court transcripts of several rape cases, read out loud by audience volunteers. (The original iteration of this work was entitled Steubenville, in relation to the Steubenville High School rape trial in America, but it’s worth noting that this new Jane Doe iteration explicitly eschews any geographical specificity. Despite the prevalence of American accents, we’re purposely never oriented to one location - Steubenville is never mentioned).

Other documentary textures woven through the piece are videoed interviews with university students which are re-voiced in real time by a headphone-wearing McCracken, as well as soundbites from US and New Zealand media reporting on rape trials. Finally, there are two moments in the work where the show is paused, and audience members are given the opportunity to anonymously text in any of their observations or feelings, which are then projected back to the room.

Kate first saw Jane Doe in the Q Vault at the Auckland Fringe Festival this year, so this was a second viewing. This was Rosabel’s first time seeing the work.

Kate Prior: How did you feel, walking out of Jane Doe?

Rosabel Tan: I was thinking about this. I've never needed to talk about a show as much as I have about Jane Doe - partially because it's such a harrowing experience, but also because it doesn't try (how can it?) to resolve anything.

How was it for you, the second time round?

KP: Yeah was really interesting seeing it again - before going, I had a bit of a heavy heart as I knew the kind of place it put me in last time. And you know, that kinda didn’t change; I didn’t feel any less angry and frustrated having already seen it. No less of a feeling of wanting to stand up and scream.

RT: Is that a response to what the show explores or the show itself?

KP: Um, well possibly a wee bit of both.

I mean, when I talk about screaming, it's in relation to the content – the nature of it presses down on your shoulders so you feel like you’re drowning a bit. But it’s also the way its constructed, as a layer-upon-layer accumulation. It's similar to when the piled-up textures of media clips were used in the 'trial' section of Eleanor Bishop’s and Julia Croft’s recent production, BOYS as well. It’s this practice of standing and pointing to something, in this case ‘rape culture’, by simply placing its parts out on display. The intention is to provoke conversation, and it's a laying out of 'evidence' for us to examine. But then I don't know what else. Are the shape and contours of that culture really dug into? Or why that culture exists?

RT: No, although it does hint at what lies beneath – the terrible media descriptions, the multiple moments where Karin refers to rapists as "football players, cricketers and swimmers", which I guess speaks to that idea of how expectations of aggressive masculinity feed into rape culture (although, you know, it’s not a definitive or representative list). And it was balanced with that central narrative – how something as seemingly benign as rom-coms have also fed into it as well.

But you're right that it doesn't attempt to pinpoint causes. It just shines a harsh and horrible light.

KP: Yes. And I do get that that 'surmising causes' is not the point – shining the light is its intention.

I find the use of, and almost insistence on, romantic comedies as a girl’s window into desire in Jane Doe an interesting choice. They’re not mentioned just once – rom-com anecdotes and Karin’s sexual awakening through them is brought up in about two or three different sections. (I say Karin’s, but I never had the sense this is ‘her’ story particularly, and I don’t think it matters). Those stories of sexual obsession led by screen norms are obviously there for the soft-focus nostalgia and inherent humour you can glean from that, but because of their prevalence, the piece seems to nod at them as the central sexual messaging for women growing up. And I think yes, it’s certainly there amongst everything else at that age but it’s not the gospel perhaps. It wasn’t for me anyway?

RT: Yeah totally, because then there were sealed sections, Mills & Boon and the Red Shoe Diaries (just me?)

KP: Haha.

In saying that, I can see that they’re meant to serve as a counterpoint to Karin’s eventual realisation of a kind of truth about love – when she just really feels safe with someone, and that it’s not about all that rom-com shit.

RT: Yeah, and that sex positivity is one of the antidotes to rape culture.

KP: Yes. It’s simply that there are these masc/fem universes that seem to be set up in Jane Doe of sport on one hand and rom-coms on the other, and I don’t know if it’s a helpful binary.

RT: You know, I've been thinking a lot about my response to the show, and how I made that comment the other night about it feeling like a particular strand of white feminism, but I want to take that back now because it’s an unfair criticism to levy. It’s like: what did I want? I think it's a real testament to the show that I walked out of the theatre with such an unquenchable hunger for more. And what I found really remarkable is how it created a genuine space for me to think about my own specific (and sometimes different) experiences, and how it made me want to talk about it with you afterwards. I think if a show can spark conversations like that - important conversations that we aren't having enough - it's doing something really incredible.

KP: Yeah you’re absolutely right, and that squarely feels like it’s intention right; to provoke conversation. I remember you saying the word ‘triggering’ afterwards, and that you weren’t sure if you’d fully bought into the reason for overloading an audience in that way. And I guess that’s because at base it’s simply a provocation for conversation. The interesting thing though, is who is being provoked?

RT: I was wondering about the audience. There were points where I wondered if it was really meant for women – I think it’s because of the way some of the narratives are framed - like the idea of rom-coms teaching young women to relinquish power, desire and pleasure to men because that’s what love is. That felt like a conversation with women.

It’s not enough to say something is permissable or denounce something. What are the systems of space and action that implicitly permit or disallow?

KP: Okay, so the big question I have is around the setting for the work. It’s been performed in various university environments in the US, and to me that really feels like the home of the work. The first time I saw it, something about seeing it in a theatre space grated for me. I was interested to see if Q Loft would be made more informal at all, but we were in a traditional end-on configuration in the dark. And I felt that same frustration. Like you know, at the beginning, Karin lets us know “if you need to leave at any point, that’s fine”, and she’s intending to set up this ‘space’ as a different kind of space. But the guy in front of me is swigging on his Pinot, waiting for the ‘show’ to start. You know what I mean?

RT: Ha yup.

KP: It’s about the culture of spaces. The fact that Karin acknowledges that at the beginning is great, but that ignores the fact that all spaces have a culture, and you get an audience into an end-on theatre environment and turn the lights down, and it’s a big deal for some people to leave that space.

I mean in a way, it’s an interesting metaphor for what culture is; it’s about systems of consensus. It’s not enough to say something is permissable or denounce something. What are the systems of space and action that implicitly permit or disallow?

RT: Yes! It definitely felt more like the ‘performance’ of consent than actual consent in that space. But then we're talking about two different cultures and the show isn't built to deconstruct a theatre one.

KP: Yes I agree, and I’m making that connection, the show doesn’t explicitly.

But yeah, I would really like to see this work in what feels like to me, it’s home - in gyms in high school or university spaces, with conversations exploding after it, like I’m pretty sure they have. And in the LIGHT.

Obviously, there are financial and industry reasons why we’re seeing it in a theatre - it’s to make some money before taking it to Edinburgh, and to offer a more visible platform for this director and I get that, but it doesn’t feel like trad theatre spaces are at the heart of, or part of the original intention the work.

RT: But it definitely feels like a vital aspect to the show. And holy hell, totally agree that every young person should see Jane Doe, and have the opportunity to talk about it after.

KP: Yes, I hope it does when it returns - I feel like it’s invaluable in those environments.

RT: I wasn't sure about the attempt to localise an otherwise American story – like I'm not sure what the two interviews with New Zealanders added in the mix of mainly American students, and I think they risked feeling a bit like an afterthought.

KP: Yeah I did wonder if the title could remain geographically tied to Steubenville. We know that it’s (sadly) a ubiquitous experience and we understand that, so do we need to explicitly be told that this could be a general ‘anywhere’? I’m not sure.

RT: Yeah, I think one of the tricky aspects of using 'Jane Doe' is that it implies it could be anyone, and there are moments that try to acknowledge the breadth and range of experiences that people can have, but it's so hard to do that throughout without losing your voice.

KP: Yes, I agree. By reframing the work under the ubiquitous umbrella of Jane Doe I’m more inclined to take the cue to read the rom-com experience (for example) as ubiquitous, because that’s what the title sets up. And you know, it’s not. But yeah, I might forgive it for not speaking to my way-less-rom-coms experience if it situated itself more specifically perhaps!

On another note, this second time especially, I really valued listening to the audience members who had got up to read the transcripts. At one point a woman was playing the male friend of the defendant who was a witness, and it’s a really interesting thing to have certain voices and bodies – in this case a female voice and body – standing in for what is a male voice and body. It’s the same when Karin gives her own voice to the voices of the interviewees by means of a headphone verbatim technique. (Really skilfully I might add!) The form of voices jumping round bodies – it offers a quality of our bodies just being vessels, like we’re empty containers or something. Containers for culture. It lifts individual ‘identity’ off the conversation in a way, which is interesting.

RT: Yeah that ‘cross-casting’ was great because it created that space to think about all the ways we can be complicit in rape culture, including how inaction or silence is the same as endorsement.

KP: Yes, yes!

RT: I will say that some of the 'casting' on the night we went added an unexpected (and weird…?) layer... But I guess it makes an important point about how any of us could occupy any of those positions at any of those times.

KP: Do you think there’s an ‘American’ quality about the work?

RT: I don't think the story is uniquely American, but obviously the trial, the videos and Karin's accent all give it that quality. That's what I meant before about the two New Zealand voices feeling token, because so much of what's in there is universal (across the Western world at least) so I don't know that it needs to be localised to New Zealand?

KP: When it comes to the interviews it’s interesting because there is a verbosity to the American students – Americans are so happy to talk about themselves – which is so different to New Zealanders.

RT: It did give everything a distance I'm not sure I would've felt otherwise. But I'm kind of grateful for that.

KP: Yeah, I know what you mean.

Do you think it's an optimistic show?

RT: Do you think it's an optimistic show?

KP: Hm, good question.

It doesn’t feel that way initially perhaps… But yeah, I feel a lot of optimism in the voices of the women who are interviewed. I feel optimism in their sharpness, and their sort of incredulity, and their laughter.

And I feel optimism in that moment when Karin is talking about desire and remembering the feeling of just really wanting have sex with someone; like owning and understanding that feeling. That’s one of the strongest moments for me.

RT: I think it's so cleverly optimistic. That incredulity you mention definitely; the recognition that those experiences are unacceptable. And also I think the show as a whole felt like an act of optimism, because all it does is present something, and trusts you'll want to talk about it and want to work towards change, rather than telling you that you should.

KP: That’s so interesting that you call it an act of optimism after our initial reactions the other night! I wonder if that’s the feeling after the original heat has burnt off too. Like that heat of discomfort and anger turns into vapour, and you’re left with the sensation that you gotta use that. I mean, I really like it and I think I agree.

RT: I know! This is such a different conversation to the upset, ranty heartfelt one we had the other night, but I think that's also because the show is an act of trauma. Which is such a risk! You leave feeling like you've been part of something horrible, and in that moment it's hard to separate those feelings from the work that led you there.

I think it also means that a lot of responsibility is placed on the audience, and that becomes a really important consideration if you're taking it to schools.

KP: Yes you’re right.

RT: But I do think it’s rare to have those kind of intense responses to a performance, and for that response to shift and adjust so much over a couple of days - maybe that’s because we don’t see this mode of expression very often.

KP: Yeah when you’re not dictated to, there’s so much more capacity to examine your own response isn’t there. I definitely think that's the value of a journalistic form such as this.

Interestingly, on the night we went, one of the responses on the screen was “I’m taking in the information of all parties”. I sort of stared at it like, wow. It was a reminder that in that room there were still audience members reading this in a completely different way to me. And oh boy, I would have liked to talk to them afterwards.

Amendment: The introduction to this piece originally noted that the show contains the court transcript of the Steubenville High School rape trial in America. This is not correct. As amended, this section of the show contains text inspired by several cases.

Jane Doe runs from June 6-17 at Q Theatre. Tickets available here.