Not All Knowledge is Yours to Share: A Review of How to Live Together

Dilohana Lekamge reviews How To Live Together, an ambitious and sprawling exhibition that probes community and solitude, and celebrates the radical act of sharing knowledge.

How To Live Together is an ambitious and sprawling exhibition that probes community and solitude, and celebrates the radical act of sharing knowledge. Dilohana Lekamge reviews.

Creating cohesion in a land that is home to its Indigenous people, its colonisers and its migrants is not easy. It can be difficult to find your place in a colonised country when you yourself have adopted this country as your home. Finding common ground and creating common goals is trying when there are many cultural perspectives at the table, each with different values and practices.

How to Live Together, curated by ST PAUL St Gallery’s Assistant Director Balamohan Shingade, incorporates several of these cultural perspectives, with works spanning video, photography, installation and performance. The exhibition poses two questions: “What is the intimacy we must develop to create a community?” and “What is the distance we must maintain to retain our solitude?”

Its core principles are rooted in the curatorial intention of incorporating idiorrhythmy – a term used by French philosopher Roland Barthes in his lecture series How to Live Together, which the exhibition is named after. Taken from practices of communal living in monasteries, idiorrhythmy, as described by Barthes, refers to “the lifestyles of monastics who live alone but are dependent on a monastery”. Out of a monastic context, we can take this to mean simply the individual rhythm of one part of a greater whole.

To consider the exhibition as a whole is an intentional impossibility. It’s made up of pieces that by their nature are circumscribed by their duration, physical location and intimacy. Even viewing all of the onsite works – including the three long-form video works, the longest being 1 hour 20 minutes and the shortest 32 minutes – at least once each would require a full day of dedication. There are a further seven works and projects that are incorporated in the exhibition yet occur outside of ST PAUL St’s opening hours or outside of the gallery.

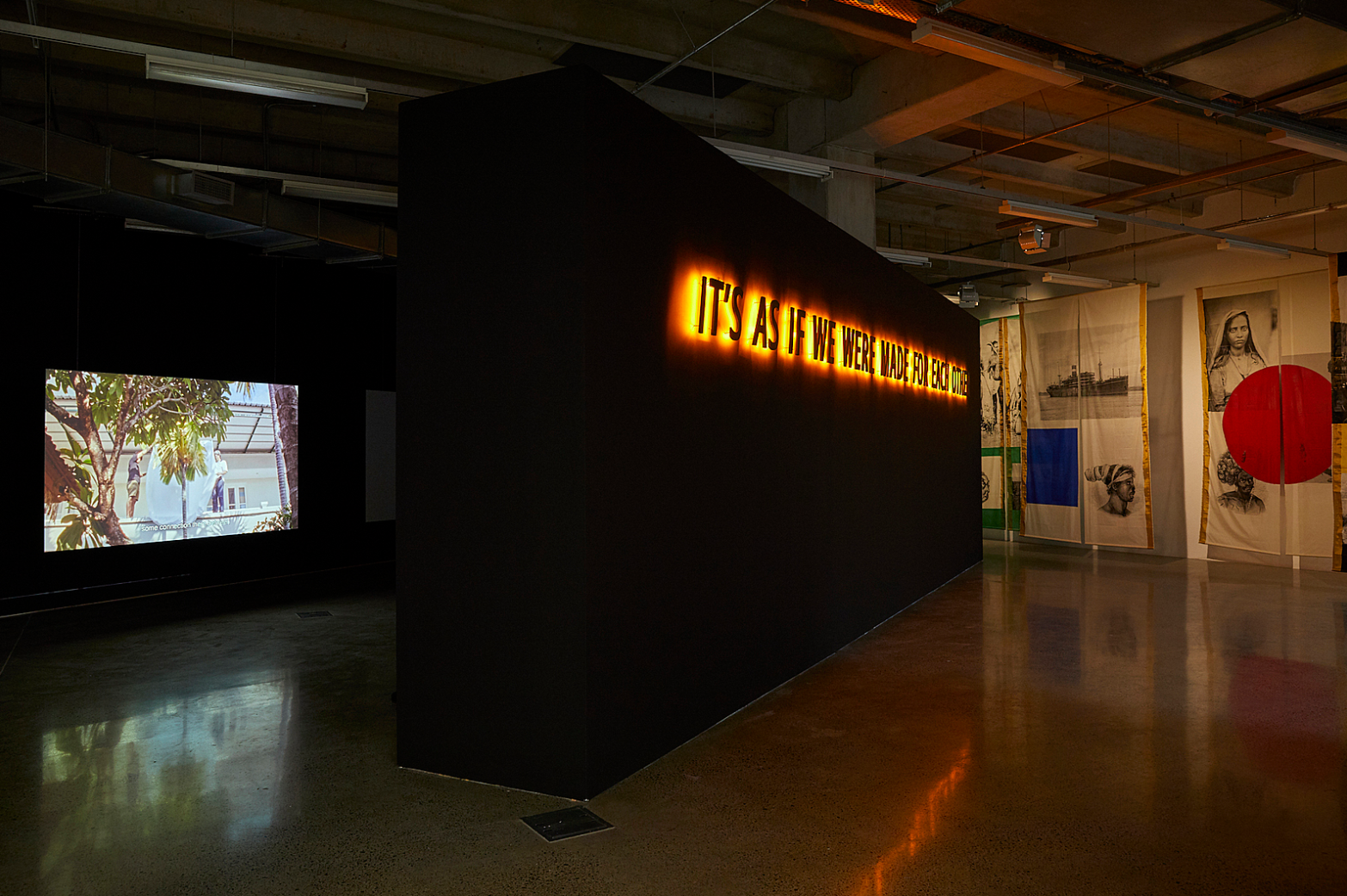

In Gallery One, at the centre of the space, is Deborah Rundle’s large-scale light installation that reads IT’S AS IF WE WERE MADE FOR EACH OTHER in italicised black font. Backed by a black wall, each letter is illuminated by a gradient of orange and red light, creating an eye-catching phrase that becomes the centrepiece and visual introduction to the exhibition space. “It’s as if we were made for each other” is, as stated in the exhibition programme, a common romantic cliché, but conspicuous outside of a romantic context. Taken at face value, the optimism in the statement “It’s as we were made for each other” suggests that living together could be a simple task, but the briefest glance at our world’s history proves that is actually very difficult to achieve. It is hard to uncouple this sentiment from our current global situation in the midst of horrific terrorist events, aggressively nationalist political leaders and wider global acceptance of nationalist ideals. It is disappointingly clear that ‘we’ – whether this refers to the collective ‘we’ of different cultures seen in this exhibition, the ‘we’ that is our multicultural population in Aotearoa, the ‘we’ that refers to the world’s population, or even the ‘we’ that two people can become – we are finding coexistence difficult, to put it lightly. The phrase seems either saccharin in its optimism or, if read with a sarcastic undertone, eerily dark, implying that maybe there is no hope for us all to coexist.

Next to Rundle’s text work and mirroring its immense size is Brook Andrew’s Inconsequential I–VI, a succession of textiles that couple together the Indigenous cultures of Australia and Kerala. Each piece, made of sari material, hangs from the ceiling to cover one entire wall of the gallery. By using archival images from both cultures, printed onto the material and partnered with blocks of bold colour, the work highlights the connections and similarities of the cultures, both native and colonised.

The black partition that acts as the backdrop to Rundle’s work also blocks light from entering a dark cinema-style space with built-in seating created for viewing three long-form videos. The dark screening space is split up by three screens; the left screen for Sriwhana Spong’s The Painter-Tailor, the middle shows O Horizon by The Otolith Group and the right screen shows Christian Nyampeta’s Sometimes It Was Beautiful.

Nyampeta’s film displays a kind of coexistence that is dispersed over a long timeline, and rooted in a single place. A whole host of thinkers and people of historical significance – including Gabriel García Marquez, Robert Mugabe, Winnie Mandela and Crown Princess Victoria, to name a few – have at one point visited Stockholm’s Museum of Ethnography. The film brings together all these people in their different eras to form a kind of camaraderie, unbeknown to the film’s subjects – showing that community can be formed in ways that aren’t conventional, but can simply be the result of happenstance.

Sriwhana Spong follows a more personal timeline in The Painter-Tailor, which follows her research of her late grandfather’s occupations as both a painter and a tailor in Bali. The camera follows idyllic images of her family home showing its interior, architecture and the people who have occupied it. It pans over the paintings created by the artist’s grandfather, showing the intricate details and bold colours. The golden hue of the footage makes it resemble a home video filmed on a Handycam. This line of enquiry continues into the gallery’s window space facing onto the street, where Spong’s Death of Bhoma hangs. The fluid, bold markings on the large canvas are made in Indian ink, reflecting the poetic influences in her grandfather’s last painting. Both works give an intimate glimpse into the history of Spong’s family.

O Horizon presents a warm-hued approach to learning through connection with people, land and other living beings.

Otolith Group’s video work O Horizon is centred on Santiniketan, a school in West Bengal founded by the poet Rabindranath Tagore. The short-film-length video work depicts the lessons taught at the school, the rural forested area where the school sits, and its deep and rich connection with the earth from which these forests grow. The warm mustard yellow of saris and uniforms in the film mirrors its soft focus on sun and moonlight. O Horizon captures a passion for a well-rounded experience of education that does not begin and end in a classroom, nor is focused on academic intelligence. It presents a warm-hued approach to learning through connection with people, land and other living beings.

O Horizon hints at another key influence on the curation. Tagore wrote that “education should never be dissociated from life”, which is a sentiment echoed by the structure of the exhibition. Parts of the exhibition reflect the syllabus and topics covered by Auckland University of Technology courses. This structure shows ST PAUL St’s willingness to be a symbiotic component to the university, its student body and curriculum, instead of a fully separate body with its own motives, goals and audience – a tradition that is rife in university galleries throughout Aotearoa. The abundance of knowledge, care and colour in this film combined with its theoretical connection to the principles of the exhibition, positions it as an integral and captivating piece.

In Gallery Two, the large untinted window lets outdoor light into the space. On Wednesday afternoons, for the duration of the show, Chris Braddock invites a group of visitors to engage in dialogue. The gathering takes place at the end of the space, and is formed to focus more on the process of thinking than the content of the conversation. Inspired by theoretical physicist David Bohm, Braddock’s intention is to challenge the notion that one’s thinking is one’s own. When the workshops aren’t taking place the empty mat and the cushions mark the place of past and future interaction, an absence of people and their eventual presence.

Six TV screens installed in front of the window show a range of shorter video works – some with and some without headphones. In a trilogy by Pallavi Paul, the recurring character is the poet Vidrohi, known for his attachment to Jawaharlal Nehru University, in New Delhi, staying involved in the student protests far beyond his time studying there. Paul uses Vidrohi in this series to investigate the inevitable subjectivity of documentary material, by weaving imagery that bounces between memory, experience and reality.

An energetic pop song about rekindling a relationship and the act of parodying your dad seem like off-kilter additions to this show, given its academic and theoretical basis, but they are welcome inclusions.

The incongruent sound of Justin Beiber’s ‘Sorry’ is inescapable in this space, mingling with the sound of the narration in Paul’s videos even through headphones. Beiber’s energetic and catchy song plays as part of Bridget Reweti’s video work Tauutuutu, recorded in 2016 at the Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency in Canada. The work shows the artist with other participants of the residency, exchanging knowledge in the snowy outdoors. Their interactions range from call-and-response vocal warm-ups to photography to dance moves.

On the same reel, Hetain Patel’s To Dance Like Your Dad is a short split-screen video work that shows, on the left side, the artist’s father enacting part of his job in a demonstrative video tour of his workplace, a car conversion workshop. The right half shows the artist in an empty room, synchronising his gestures with his father’s, movement-for-movement but sans machinery, in a straight-faced choreographed mime of his father.

These two video works, inserting an energetic pop song about rekindling a relationship and the act of parodying your dad, both seem like off-kilter additions to this show, given its academic and theoretical basis, but they are welcome inclusions. To Dance Like Your Dad and Tauutuutu introduce a more light-hearted comedic element to the exhibition, playfully using mimicry as a form of response and learning.

The focus on gesture in Reweti’s and Patel’s videos continues in two neighbouring videos by Sam Hamilton. Sovereignism and Sovereignism Amendment #1 explore the idea of amendment through the use of typographic symbols, such as an asterisk and an ampersand. The symbols are printed on flags and rowed over to a small island, indicating that what seems like a minor adjustment can influence the meaning of a phrase, and points to the forever evolving use of language.

Reweti’s Club Field photo series also appears in Gallery 2. Idiorrhythmy has informed the way the way the series is displayed, with only one print on the wall at any given time; during the exhibition, it is swapped out for another in the series. The photographs were taken while visiting ski-field clubs across Aotearoa. Reweti chose to examine these groups because they function as non-commercial entities operated mostly by volunteers, creating a community that exists to maintain each alpine region.

One of the parts of the exhibition occurs outside of ST PAUL St Gallery, and outside of the city altogether: James Tapsell-Kururangi’s residency is located in his late grandmother’s home in Rotorua. As stated in the exhibition programme, he interacts with the home and its contents with care, immersing himself in his memories of his grandmother – not to create a tactile artwork for displaying, but to undergo a study of relationships.

Aqui Thami, founder of Sister Library, a community-owned, feminist library in Mumbai, also undertook a residency as part of How to Live Together. Thami collaborated with local storyteller and social commentator Qiane Matata-Sipu by participating in NUKU, a project of storytelling that Matata-Sipu began in 2018 to engage with Indigenous women’s histories and continue the traditions of the passing on of knowledge through oral communication. Thami’s residency at Auckland’s Samoa House Library was framed by a goal of exchanging knowledge. Both Sister Library and Samoa House Library are sustained by their communities and fill a very obvious gap in the sharing of resources in these respective communities.

The viewer must accept that some aspects of this exhibition are not shared with them and are not theirs.

No physical display of either residency appears within the exhibition space, which demonstrates the commitment to the curatorial premise that all elements of this show cannot be wholly consumed and that ideas of solitude and community remain central. In this circumstance, the viewer must accept that some aspects of this exhibition are not shared with them and are not theirs; rather, they are for a smaller audience of the artist’s choosing.

Another example of this is Poata Alvie McKree’s series of Art as Medicine gatherings, to which the artist invited only women, and the remnants of which sit in Gallery One, in front of Rundle’s installation. Candles, dried flowers and ferns, and a cast pelvic bone with a lit candle in its centre are all placed on a small, low table covered with a patterned rug. Like the cushions and mat left for Braddock’s dialogue group, this scene acts as a marker indicating that these events took place. It displays the human interaction with the space without intruding on the intimate nature of the ceremony. Like the residencies, McKree’s gatherings demonstrate the balance between seclusion and contribution to the larger project.

In 5 Minutes, Kalisolaite ‘Uhila proposes that audience members engage in contemplative and non-verbal communication by sitting silently in the Albert Park rotunda on Monday mornings at 9am for five minutes, as the title instructs. For the duration of the exhibition, the gallery staff do just that. This provocation to be meditative echoes the more contemplative exhibition structure that ST PAUL Street adopted this year.

How to Live Together softly pushes its audience away from the static conventions of exhibition viewing, to interact with continuously evolving form

By using iddiorrhythmy as a guiding principle, How to Live Together demonstrates a less rigid form of group exhibition. How to Live Together softly pushes its audience away from the static conventions of exhibition viewing, to interact with continuously evolving form, parts of which are not always available to each viewer. The impossibility of experiencing the exhibition in its entirety pulls sharper focus onto the curatorial decisions that have shaped the show. Its ambitious curatorial premise required particular care for each of its parts – ensuring that each piece contributed to the fluidity of the exhibition’s provocation while exploring its own line of enquiry. The large variety of work interacts with these inquiries, examining familial, ancestral, cultural, philosophical and personal connection. The combination of all of these contexts can feel overwhelming, but once it is accepted that it is impossible to join in on all of these conversations, there is less pressure to engage with it all.

Knowledge is sacred and sometimes that means that we are not all universally welcome to have it.

How to Live Together does not claim to be an instructional guide to living together, but a proposition to contemplate these ideas. It doesn’t seem like the intention of the exhibition was to answer the two initial questions posed about intimacy, community, distance and solitude, but perhaps to survey the questions themselves. Each piece of How to Live Together is complex and full of rich histories that engage with these perplexing queries to create dialogue, instead of providing answers. The assembly of these works, all of which share immense generosity and care in their research and creation, made experiencing this exhibition a welcoming and plentiful encounter.

By not having all elements of the show available to any one viewer, the exhibition also addresses the nuanced notion of the exclusivity of knowledge as an integral part of the practice of coexistence. Though this sentiment might not provide all the solutions on how to create a place that is both for the individual and shared with others, the practice of sharing knowledge has the ability to make coexistence more pleasant. The nature of this exhibition shows the audience that knowledge is sacred and sometimes that means that we are not all universally welcome to have it. It is not owed, but shared. How to Live Together suggests that its visitors respect the absence of knowledge that is not theirs and care for the knowledge that is shared with them.

How To Live Together

ST PAUL St

12 July 2019 – 18 October 2019

Feature image: The Otolith Group, O Horizon, 2018. Film still. Courtesy of the artists.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the ST PAUL St Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.