State of Play: A Review of Johnson Witehira's 'Half-blood'

'Half-blood' uses parallel games to explore the history of Aotearoa New Zealand, writes Lana Lopesi, and it's impossible not to get involved.

Half-blood uses parallel games to explore the history of Aotearoa New Zealand, writes Lana Lopesi, and it’s impossible not to get involved.

I had that feeling – that niggling feeling you get when you take someone from outside the art community to see an exhibition. It’s a feeling of the unknown that makes you question how much you need to mediate the viewing experience, and whether you might need to apologise on the car ride home.

“Are you just going to stand there, or are you going to bash the whale?” my partner asked me, while I was trying to work out how to use an Xbox controller at Johnson Witehira’s current exhibition, Half-blood. As you walk into Objectspace, you’re greeted by two large video projections. In front of each is a bench seat with a single white controller on top. My partner – who has grown up with gaming devices, from a 1980s Sega console to the recently released Playstation 4 – was far more familiar with the language of Half-blood than I was. He was the one mediating my experience.

Artists have played with digital technologies in various ways since the 1970s, and will continue to use these technologies as they further develop. With Half-blood, Witehira doesn’t merely make reference to digital technology, he directly borrows from it, using gaming as a form of making. This means that those with an understanding of gaming can connect with the work faster than art audiences. As a result, the exhibition invites different visitors and a different set of criticisms.

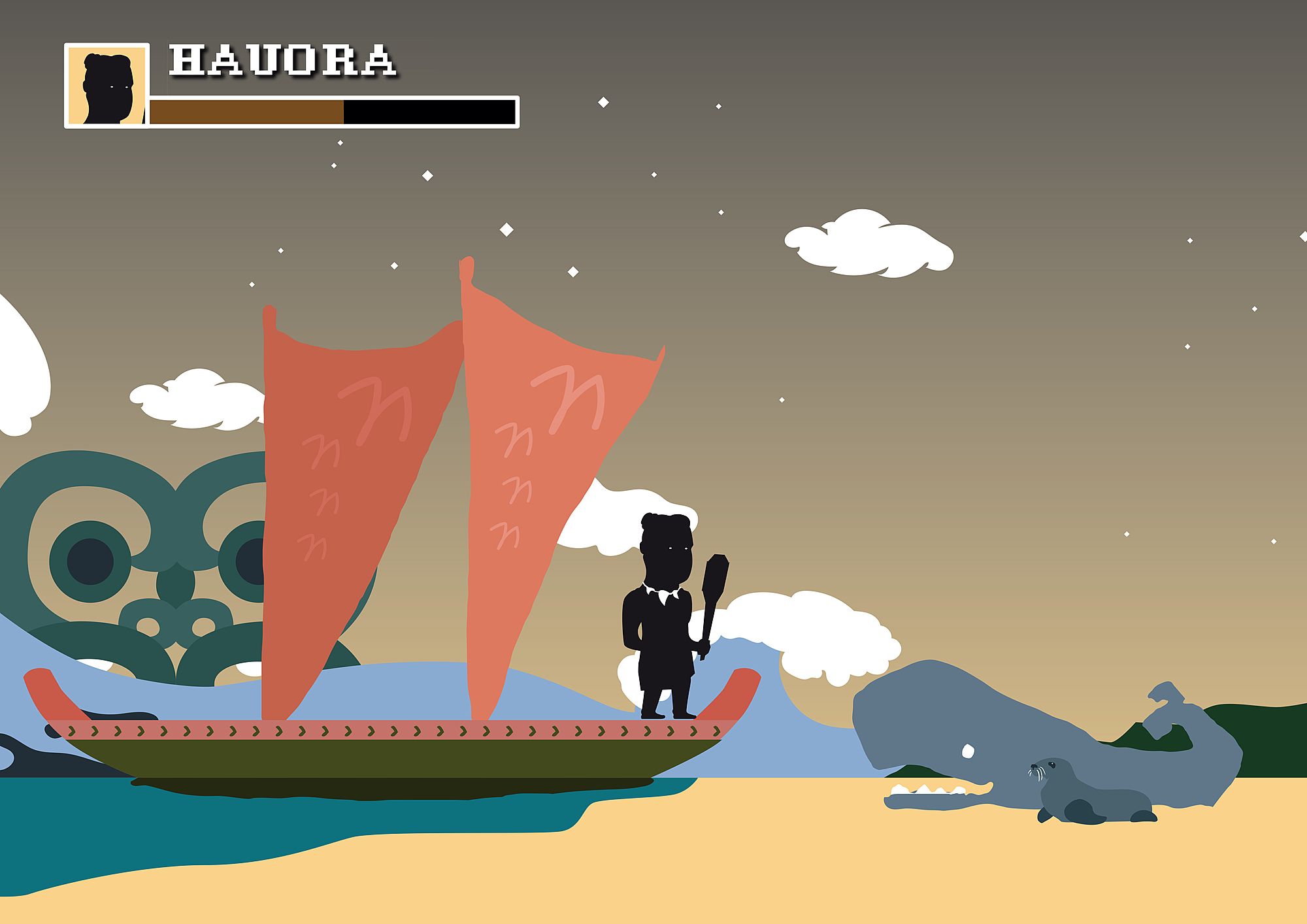

Half-blood comprises two ‘games’, both called Māoriland Adventure. As games they’re not complex. Each uses a linear storyline, with the player progressing across the screen. The playing time is about three to five minutes each. One game shows Māori arriving on the shores of Aotearoa. Your character must kill animals by bashing them over the head in order to move forward. The other game shows the arrival of Pākehā in New Zealand. This time, your character must bash Māori over the head with a bible to the point of conversion in order to progress.

Witehira’s work is visually appealing, with a slick design aesthetic of solid colours and strong imagery. More importantly, its use of digital technology makes it accessible to communities that aren’t often found in traditional gallery settings (although, in their current form, the games are hidden away behind the swinging doors of Objectspace on Ponsonby Road).

We learn more about the exhibition in the essay ‘Wheako whakarara/side by side’ by Megan Tamati-Quennell, which reveals that the title not only relates to the artist’s mixed background, but is also a term borrowed from arcade gaming slang, meaning “the act of handing over the controls of a game to a better player when half the game has been played or when half the life of the game character is all that is left”.

Research has shown how indigenous communities across the globe took to the internet as soon as it became publicly accessible in the late 1980s to early ’90s. It’s been particularly important as a platform for social activity. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s Māori me te Ao Hangarau 2015: The Māori ICT Report 2015 tells us that the top reason for Māori using the internet is social networking, quickly followed by entertainment. Māori are more likely than other cultural demographics in New Zealand to stream music and videos – and to play video games.

In Witehira’s work, the accessible and attractive gaming form is used to discuss more complicated and sinister histories. Like Mohawk artist Skawenatti’s TimeTraveller™, Half-blood attempts to fill in some of the gaps in our understanding of history. Through the game that shows Māori arriving in Aotearoa, for instance, we learn about the damage to native ecology that took place when Māori were coming to terms with their new land, and are invited to consider our own relationship with the environment.

In this Māoriland Adventure, Witehira uses only te reo Māori. On a surface level the use of te reo is appropriate because the game is set in pre-European contact, making it a linguistically accurate choice. More importantly, though, the prominent use of the language in an environment where it is not the norm makes a strong statement about inclusion and exclusion.

The social sciences have taught us to expect access to all information, especially that of indigenous people. That access comes through a language we can understand – generally a dominant one, like English. To not default to English underscores Witehira’s desire to address specific communities, and hints at a directive for the version.

It’s refreshing to walk to into a gallery space where you have to reevaluate your own interaction with an artwork. It’s impossible to stand back from a distance and ‘watch’ the work, as we so often (love to) do in the art community. Here, you literally have to play. In an era where the ‘decolonial’ and the ‘bi-cultural’ seem to be hot again, it’s important not just to have the conversations, but to have them well.

Witehira uses humour to destabilise our national history, while demonstrating an understanding of the way in which urban indigenous communities might access information. The digital is now inseparable from contemporary indigenous experience. The potential of Half-blood is exciting.