Lonely Country: A Review of Friday's Flock

Maraea Rakuraku reviews Friday’s Flock, Te Puanga Whakaari’s bittersweet nod to our agricultural heart.

Maraea Rakuraku reviews Friday’s Flock, Te Puanga Whakaari’s bittersweet nod to our agricultural heart.

A dog whistle opens Friday’s Flock, immediately followed by Dave Dobbyn’s ‘Slice of Heaven’. Dobbyn’s music pops up here and there during the story and while the choice makes me groan a little (internally), it also has me reflecting if there is any other New Zealand musician who speaks so consistently to the Nu Zild identity. The combination of Dobbyn and the story Friday’s Flock tells makes you think about how far we’ve moved from our rural roots, where ‘town’ is Feilding and ‘the big city’ is Palmerston North. It all makes you think about the impact that change has had on those who have remained, the world growing large around them.

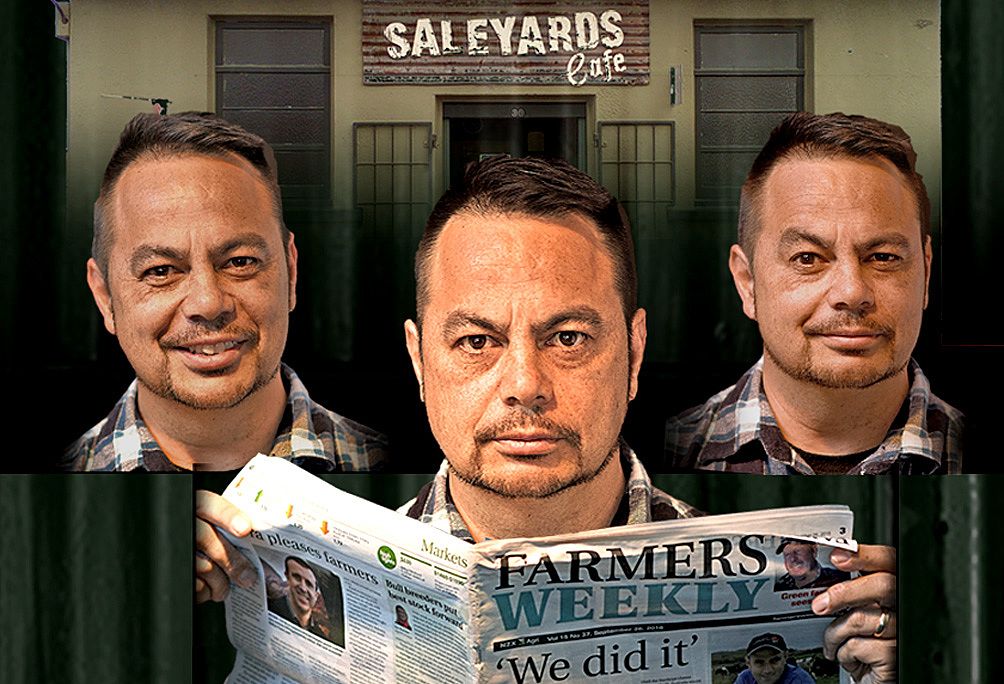

Friday’s Flock, written by Reihana Haronga and produced by Feilding-based company Puanga Whakaari, is a nod to that New Zealand identity and its agricultural heart. We’re greeted at the door of the Heyday Dome by Sam (Reihana Haronga, one of seven characters he’s written and plays). Friendly and dressed in an apron, he ushers us into the traverse set. Tables covered in red gingham flank a pathway to a counter with a specials board. We’ve entered the Saleyards Café. Sam’s the proprietor.

Sam serves customers, freeze-framing, montage-styles. We’re immediately in tune with the inner-workings of the cafe and how time moves in the play. The audience loves it too: Haronga has natural comedic timing, knowing exactly when to ham it up and how to milk a pose.

We are then introduced to the Saleyards’ regulars, like Walter and his dog Jack. Walter’s a kindly gentleman farmer. Sitting quietly with a cuppa and a newspaper, having a slight variation of the same conversation with Sam every day: everyone knows a Walter. And everyone knows or in my case loves the over-exuberant and excitable Jack. And Haronga’s so great at doing Jack, so funny and with so much to love!

Joseph, meanwhile, is a good-natured young fella. Joseph’s inherited the family farm following his father’s death. Mobile phone glued to his ear, we learn through eavesdropped conversations that he really doesn’t have much of a clue – about life, about dating and, as it turns out, about farming. Luckily for him, Walter, with his years of experience, is ready to advise. Finally, there’s a woman, unnamed (until much later), waiting for her husband.

It’s the party-lines of old, a reminder of times when farmers came into town specifically for the collection of supplies and Friday night shopping was an occasion. While there are regions of New Zealand still living this way, Friday’s Flock definitely speaks to that loss, beautifully and almost unintentionally.

It’s through Haronga’s characters we come to understand the lives and loves of a small town and the diminishing of rural New Zealand. While Walter and Joseph chat about farming equipment and Sam comments on the stock in the adjacent stockyards, the old woman reminisces. She describes somewhat sadly the impact of the Second World War on the Uncles that returned home, the excitement of shopping at the local drapery, and the courting at dances in the local hall – which is hilariously contrasted with Joseph’s attempts to strike it lucky on a dating app and Walter’s romantic suggestions.

It is so refreshing to have a story located in parochial New Zealand, hearing place names like Kimbolton and Feilding. Listening to the conversations between Walter and Joseph, I’m reminded that something very similar is probably taking place right now between two mates in any small town in New Zealand. It’s unpretentious and grounded. It’s the party-lines of old, a reminder of times when farmers came into town specifically for the collection of supplies and Friday night shopping was an occasion. While there are regions of New Zealand still living this way, Friday’s Flock definitely speaks to that loss, beautifully and almost unintentionally.

There’s a strong sense of community, and of the isolation that’s as a result of a slow disappearing of rural men, rural women and a rural way of life. Walter and Joseph tell each other about their lives while Sam listens, all of them seemingly oblivious to the woman talking directly to us. Sam begins scenes (presented as four vignettes) by chorusing how much he loves the current season and updating the Specials board. And there’s hints that Joseph’s father died tragically, possibly by suicide – a discussion that places this work now and brings to mind the article by New Zealand farmer Dan Mickleson.

It’s relevant. It’s current. It’s where we’re at. Haronga has tapped into an aspect of our contemporary identity that is yet to feature on New Zealand stages. And the way he delivers it is in a simple telling. But it could be explored in a deeper way.

Haronga’s onstage and under full lights throughout, which takes bravery; after all, there’s nowhere to hide and there’s an additional level of audience scrutiny! Partway, though I find myself wishing that the character transitions were just that little bit slicker and the characters were clearer and bigger. Haronga’s Joseph is youthful, with a lanky gait and the most obvious of accessories, the mobile phone, but the unnamed woman is defined by cliche, with her high-pitched voice and delicacy. Even so what she talks about is compelling.There’s also room to grow Walter, who really is the heart of the piece. Haronga captures his characters with physical performance and props, but that means that Walter’s diction – an older, rural accent – and language are so subtle and inconsistent that they’re difficult to recall. In Hone Kouka’s I, George Nepia, one of the characters says “Byjingoes”. I was immediately reminded of my koroua, who were Nepia’s peers, the type of men they were and the world they lived in. This grounded the work in something sensory and evoked an emotional response.

Friday's Flock gives voice to those people who we rarely hear from on their terms, which is true to the kaupapa of the Kia Mau Festival and one of its strengths.

I know that Haronga and his director, Karla Haronga, are up for that because of their use of ‘Blue Smoke’. The refrain to this old folk song plays every time the unnamed woman speaks, and it’s particularly lovely. At first. On loop? Not so much. Her eventual resolution, though – and the song’s, too – is compelling, strong and very beautiful.

Haronga switches it all up when the Stock Agent enters towards the end as well. He’s big, beautiful and, by the guffaws of laughter, accurately-presented. And then we meet the Swedish model Hana. A largely silent presence, only ever spoken about, her arrival is one of Friday’s Flock’s most touching moments. They help the last third of play flow so easily toward its conclusion, revealing surprises that can be guessed at but are still very moving and satisfying story arcs despite there being no tension. This contributes to a very tidy, very complete thing, but filling out some two-dimensional characters (like Sam) could add texture to the bones of this otherwise lovely piece.

I’m reminded how sometimes the most beautiful rendering can happen in the simplest of stories and how fine a task it is balancing showing with telling, and how sensory elements, used sparingly and carefully, enhances the storytelling. Friday's Flock gives voice to those people who we rarely hear from on their terms, which is true to the kaupapa of the Kia Mau Festival and one of its strengths. As is, too, presenting indigenous works and artists in various stages of development and career. It’s like a hākari. You can pick and choose what you feel like sampling. It’s diverse. It’s exciting. It’s boss. Ka ki te puku.

Friday's Flock ran from Thursday 8 to Saturday 10 June at

BATS Theatre, Wellington.

For more information about Friday's Flock, go here.

Header photo by Dennis Price.