Review: Fallout: The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior

Sam Brooks reviews Fallout: The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior

As the title suggests, Fallout: The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior, is about the bombing of the Greenpeace ship by two French agents in 1985. The Rainbow Warrior has achieved an almost mythic status in New Zealand history. It’s a symbol for those who lived through the time, and for others it’s something they might’ve studied briefly during social studies or history, somewhere along with Kate Sheppard and the Springbok Tour. It's seen as an event that is remembered, rather than an event that someone once lived through and experienced.

What Fallout does is try to turn an act of remembrance into a piece of drama, and it is only intermittently successfully at that. Bronwyn Elsmore’s script uses a verbatim style, think Munted or the simply titled Verbatim, and slides in and out of time very easily. With a large group of characters, from people who met the French agents to New Zealanders living in France to Greenpeace activists at the time, it details the events of the Rainbow Warrior bombing, including the lead-up and aftermath.

Reconstructing an event like the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior in the way that Fallout does is a difficult task. On the one hand, the writer has to be truthful to the facts of the event: Two French agents bombed a Greenpeace ship heading for the Mururoa Atoll. A photographer died. The French agents were caught very quickly afterwards. However, on the other hand, the writer has to graft a dramatic arc onto that event that might not be there naturally.

When you look at the Rainbow Warrior bombing from a top-down view, there’s a lot of conflict, but primarily on a political level. The implications of an ally nation engaging in an act of terrorism on our soil is tremendous, and there’s a lot to discuss in that, especially for what it meant for New Zealand and French relations after the fact. However, it’s very hard to engage with that in a verbatim style, largely because you’ll be talking about the aftermath of the event, and using the voices of people who probably went there. It might make for a more interesting and heady play, but that’s not the focus of this play. The focus of this play is the people who were there.

However, this focus robs the play of one of the essential pillars of drama: Conflict. There’s an inherent lack of tension in this retelling because there’s nobody is on the other side. Nobody in the play is pro-French, pro-bombing, which is entirely understandable. For one thing, I’m not entirely sure those people exist in New Zealand so trying to represent a viewpoint that might not actually exist, or provide any useful commentary on the event the play is retelling is a fool’s errand. However, it means that the play ends up being a very one-sided piece of storytelling, and the inherent drama of the event isn’t enough to keep us engaged. We know where the story is going and we know how it ends.

This lack of conflict would be easy to forgive if there were characters to hold onto, but the script also lacks that. There’s a wide range of characters, and although a few stand out in the memory, like Kerry Warkia’s New Zealander living in France or Fasitua Amosa’s policeman, this is largely due to performance. It’s not only the amount of characters, but the lack of definition in character voice that makes it difficult to hang onto. The characters speak in a similar, vaguely defined voice, and although there are clues in performance and context to determine between them, too often we are left figuring out if we’ve seen a certain character before and then we’re hearing the next character speak.

Verbatim is at it strongest when it highlights and uses voices we haven’t heard before, whether it’s the murderers of Matthew Shepard in The Laramie Project or a woman who’s daughter has been murdered in Verbatim. These plays reveal new things about events that are so far away from our own lives, whether it’s geographically or emotionally, and they lend a human element to things we have only heard reported in the news.

Fallout lacks this kind of insight, half by design, there’s not much to actually reveal about the Rainbow Warrior and the people involved with it, none of the information is hiding from a curious. The way it’s told, with a large amount of characters, none of whom get their own significant character arc or form part of a larger dramatic arc, prevents the insight that makes verbatim theatre so special. It makes the Rainbow Warrior an event that it important because we’re being told that its important, rather than showing us why it’s important.

Where the script does succeed is as an educational tool. Even though the characters in the play are fictionalised, it’s a snapshot of what New Zealand around the time of this looked like, and how the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior changed the nation. Though the specifics are hazy, this is not a documentary, it’s a provocation to the audience to check out more of the facts about the bombing, why the Rainbow Warrior was bombed and what it did change in the long run. Fictional documents like this are often timely reminders of events that are all too easily forgotten, and even though they are rarely as engaging as the reality, they can make the complex and political relatable and human, which is where Fallout succeeds as a piece of writing; it’s a reminder that actual people went through this and their own opinions and more importantly, actions.

The greatest asset this production has is the cast. When you’ve got actors who are as open and alive on stage as Luanne Gordon and Fasitua Amosa, you’re going to be engaged throughout the piece, and they’re offset by the dogged energy of Toby Leach and the steely warmth of Kerry Warkia. They’re a strong cast and even though they never cohere as an ensemble, this play’s interpretation of verbatim theatre doesn’t allow that to happen, whenever the play does tug at a heartstring or provoke some anger, it’s because of a cast doing their damnedest.

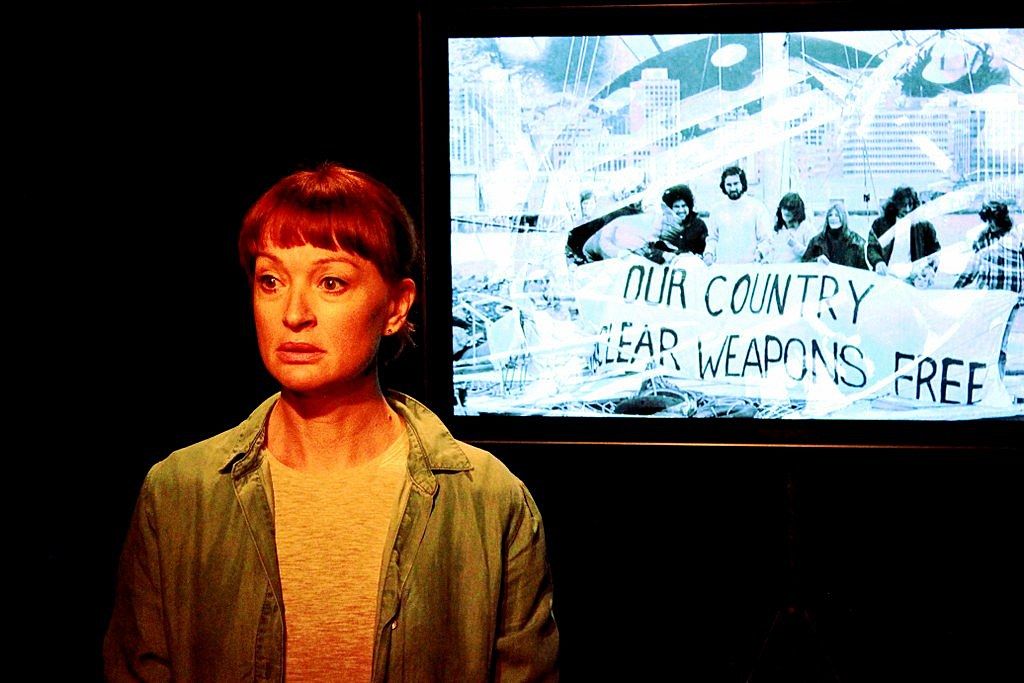

Jennifer Ward-Lealand’s direction is clean and sleek, moving through the story easily and without fuss. The integration of three screens with beautiful, evocative images is similarly clean and it lends the piece a theatricality without overwhelming the text. It would have been easy for this to be four actors talking on a bare stage, but the incorporation of the images lends the play an import and artistry that works in its favour.

There’s no question of the worthiness of this story. Thirty years after the fact, there's a generation who are not that much younger than me, who are probably unaware of the Rainbow Warrior and what it symbolized for the nation of New Zealand, and there’s an entire generation, not that much older than me, who will find depth and meaning within the play and the time period it captures. Fallout made me wish a little that I was in either of these groups, but I was left wanting for some drama, some characters and something deeper than simply remembering an event.

I respect Fallout, it’s hard not to, it is an eminently respectable production, but it didn’t move me. Remembering an event is - well - noble and even important, but it doesn’t inherently make for compelling drama.

Fallout: The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior plays at The Basement Theatre

from May 20 - May 30

See also:

Janet McAllister for The NZ Herald