Utopia Showman: A Review of Erewhon Revisited

Erin Harrington reviews Arthur Meek's new work, a slippery re-interpretation of Samuel Butler's Erewhon for our times.

Erin Harrington reviews writer and performer Arthur Meek's new work, a slippery re-interpretation of Samuel Butler's Erewhon for our times.

Samuel Butler’s satirical novel Erewhon, first published in 1872 and drawing from his time as a worker on the Canterbury high country Mesopotamia Station, retains significant cultural currency. Erewhon Revisited¸ a Christchurch Arts Festival commission presented in association with Scottish theatre company Magnetic North, is the second local encounter with Butler’s work in recent years; the other, Gavin Hipkins’ feature-length visual essay Erewhon, is a hypnotic meditation on nature and technology which toured the New Zealand International Film Festival in 2014.

Where Butler used his satirical utopia to comment on Victorian society, this marvellous production, directed with panache by Scottish director Nicholas Bone, looks ahead towards the allure of contemporary technologies, and in doing so suggests that a sanitised, self-centred colonial culture of nostalgia and erasure is as evident now as it was in the 1800s.

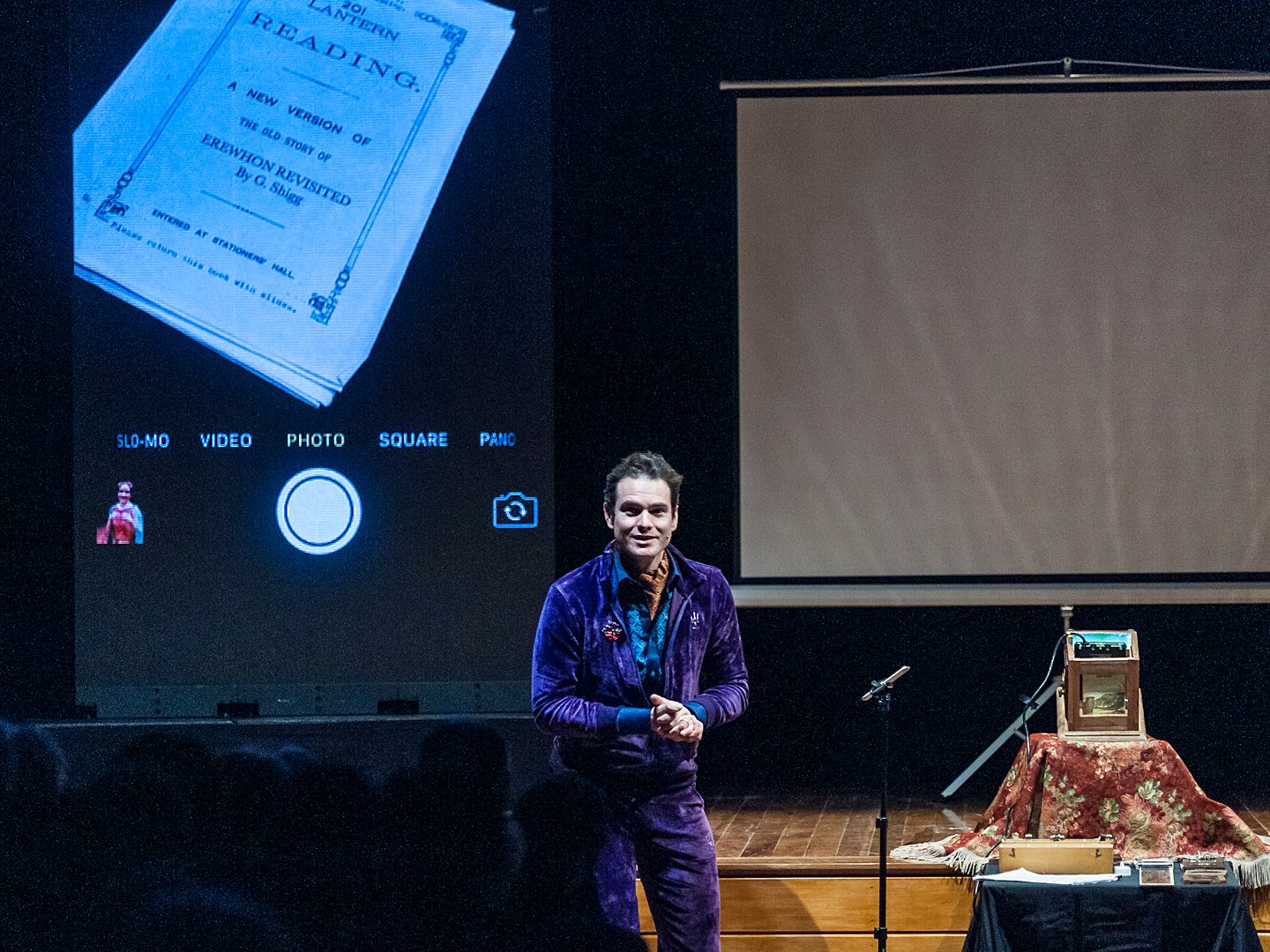

Writer/performer Arthur Meek, joined by musician Eva Prowse, loosely adapts Butler’s narrative – that of a man who finds himself miraculously transported to an idyllic, topsy-turvy country called Erewhon (or, ‘nowhere’ roughly backwards) – and places himself in the role of both actor-narrator and technical operator. The framing narrative is as coy and manipulative as that of any travelling showman: Meek acquires a box of lantern slides (from Hamilton, via trademe), enigmatically labelled ‘Erewhon’, and its mysterious contents, which include a show script, indicate that the fictional events of Butler’s original novel may be somehow based in near-unbelievable fact.

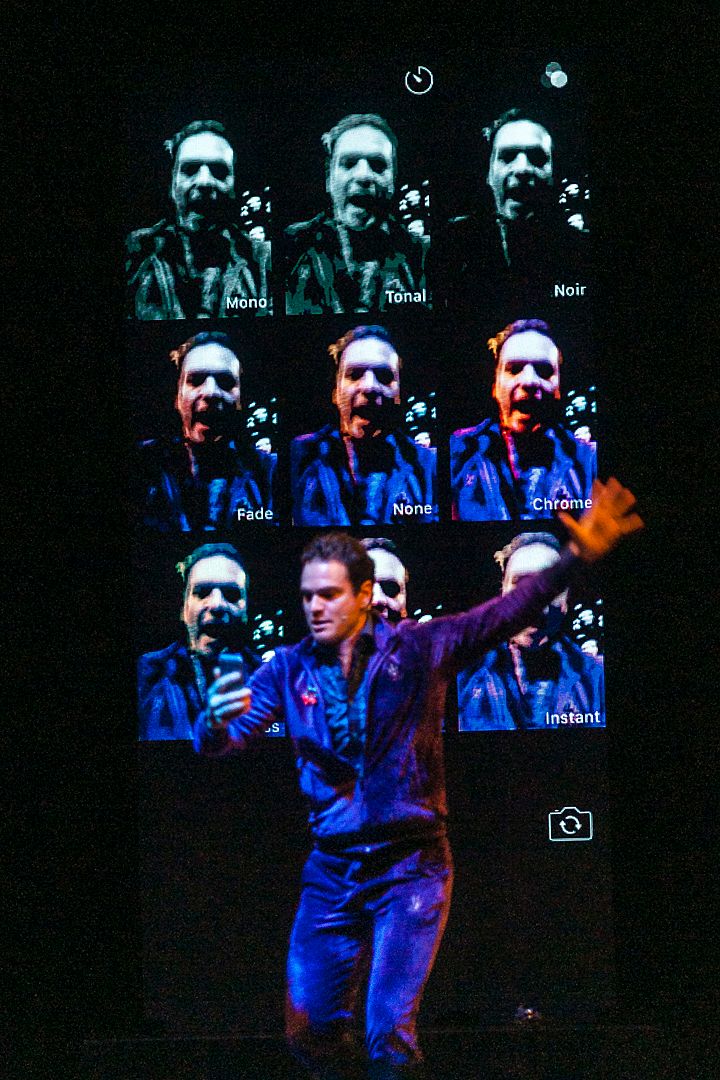

Some of Meek’s earlier work has used projected images, such as powerpoint, as a theatrical device, but here we are treated to the interplay between a long, tall LED panel that displays the screen of Meek’s iPhone, and this technology’s antecedent, the magic lantern. The magic lantern is an early image projector, dating back to the 1600s, that achieved popularity particularly in the 19th century as both entertainment and a tool for education and persuasion. The somewhat fiddly projector, which illuminates glass slides decorated with transparent paint and delicate transfers, was once lit by oil lamps and then limelight, but later models were powered by electricity. Fictional narratives would be accompanied by a read script, and diagrams and photographic slides were used to illustrate lectures. (A colleague who looks after the University of Canterbury’s collection of Samuel Hurst Seagar’s architectural and monumental lantern slides spoke recently at a symposium about the way these showings created a community of viewers, prefiguring later cinema audiences, who were connected by the shared experience of the visual storytelling and the smell of hissing kerosene). The gorgeous slides in Erewhon Revisited, designed by Sharon Murdoch and Emily Thomas, present richly coloured vistas and meld contemporary New Zealand with pastoral fantasy, alongside curious, humorous visual depictions of the Erewhonians’ foibles, customs and activities - all of which are interpreted through our narrator’s curious, but often condescending eyes.

This communal experience, and a sense of wonder at the novel manipulation of light and image (be it manual or digital), is a core feature of this show. We are explicitly acknowledged through genial direct address as an active audience whose role it is to be entranced and enlightened. There has obviously been a rewarding workshopping process – Meek himself professes that he is still learning the machine’s tricks and patterns – because the capabilities of phone and projector, as physical artefacts and image-makers, are beautifully explored and exploited. Shadow-puppetry offsets the digital manipulation of selfies; the phone’s camera exposes detail on the intricate slides, creates characters out of our environment, and reveals unseen details on the set; image and video are recorded are re-looped. I admit that I am happy to see this on the fourth night of its run, as there are very few hiccups with the complex set-up. Instead the performers, as well as the musical and visual technologies, all feel like constituent components within the whirring machine of the play itself. (That said, I'm pleased to have sat near the front; as with almost every show I’ve seen in the Great Hall this festival, sight lines can be pretty treacherous.)

We are all invited, as potential investors, to head to Arthur’s website and speculate in gentrified Erewhonian real estate (complete with moa parking spots, natch)

This whizzbangery is involving by itself, but it gestures carefully towards one of the core concerns of Butler’s satirical work, which was influenced by Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species: namely, the relationship between humans and machines, and the potential capacity for the latter to evolve in complex ways and potentially supersede their creators. We might now be slaves to our Apple and Samsung overlords, but Butler’s work was contemplative rather than strictly dystopian. Similarly, here there is no overt castigation for our fascination with technology and mediation, but instead a curiosity about its limits and potentials.

It is hard to overestimate the importance of musician Eva Prowse’s role in all of this. Prowse, to the side of the stage, offers a dynamic, shifting and sometimes tongue-in-cheek synth score that echoes the work of Vangelis (via Blade Runner) and Jean Michel Jarre or Tangerine Dream (via everything), shifting between keys, guitar, drum machine, song, and at one touching moment a very analogue violin. Meek flags, early on, that Butler’s Erewhon is a sometimes seen as a prototypic work of science fiction. The costuming further plants us in this territory: Meek, in his purple velour track suit and knee high black boots, and Prowse, in her blowsy dress, cape, and headpiece, look a little like characters from a Saturday morning sci-fi cartoon. All they need are bulbous laser guns.

This throbbing, shimmering soundscape picks up this speculative challenge: it twists the bucolic setting, and guides us steadily towards the show’s final mobius twist, which gestures towards the blithe, self-interested voraciousness of European colonial expansion. At the play’s outset, Meek reminds us that early European settlers and investors would have been enticed to colonies-in-progress such as Christchurch on the basis of idyllic images in lantern slides: “look how beautiful, and how empty, this place is – ripe for development!” As the show develops, there is also a blurring between Meek, as here-and-now showman, and Meek-as-actor, as the story’s seemingly fictional narrator. It’s not entirely a spoiler, as it’s kinda flagged in the programme, that the play’s absurd resolution whips back the curtain to reveal that we’ve been subjected to a sales pitch all along. We are all invited, as potential investors, to head to Arthur’s website and speculate in gentrified Erewhonian real estate (complete with moa parking spots, natch).

There is some sly postcolonial critique here. The Erewhon we’ve just heard about through Meek’s detailed first-person account is as fantastical and simplistic as the picture-perfect screen-printed New Zealand tourist posters of the early 20th century, which invited travellers to experience an idealised, white-washed ‘wonderland of the Pacific’. These, of course, say more about a reductive European tourist gaze than they do about Aotearoa and its people, especially those people who’d been around for centuries already. And yet, I wonder if the intent of this comic, acquisitive end point needs to be teased out a little further, to ensure that its political satire is not lost in a haze of Pākehā kitsch.

I am curious to get a sense of other responses to the show. One festival reviewer finds this all to be clever but fussy and alienating; another is positive but quibbles at the shifts in pace enforced by some of the technological faffing about. Too bad: I am singularly, utterly delighted, and would attend again if I could, if only to better look under the hood and tease apart the braided connections between fact and fiction, constructed past and experienced present, and human and machine.

Erewhon Revisted ran from 12-16 September as part of Christchurch Arts Festival