A Circle is a Sun: A Review of Mikala Dwyer’s ‘Earthcraft’

Geometry, science fiction and appropriation of ancient forms collide in the multi-faceted sculptural work Earthcraft by Australian artist Mikala Dwyer. Victoria Wynne-Jones reviews.

Geometry, science fiction and appropriation of ancient forms collide in the multi-faceted sculptural work Earthcraft by Australian artist Mikala Dwyer. Victoria Wynne-Jones reviews.

Trembling slightly, an immense crystalline form hangs before a window. Cool winter light catches its facets and its glasslike surface glows white. In barely perceptible yet perpetual motion, it shifts in response to visitors’ movements and indoor air currents. Like a shard of ice it seems rimy to touch, as though water might slowly drip from its underside – though in fact it is made of plastic.

This object is part of Earthcraft by Australian artist Mikala Dwyer, commissioned for the East Ramp of the Len Lye Centre in New Plymouth. Encountering the multi-part installation is like embarking on a kind of quest: its structure is episodic; one thing follows after another.

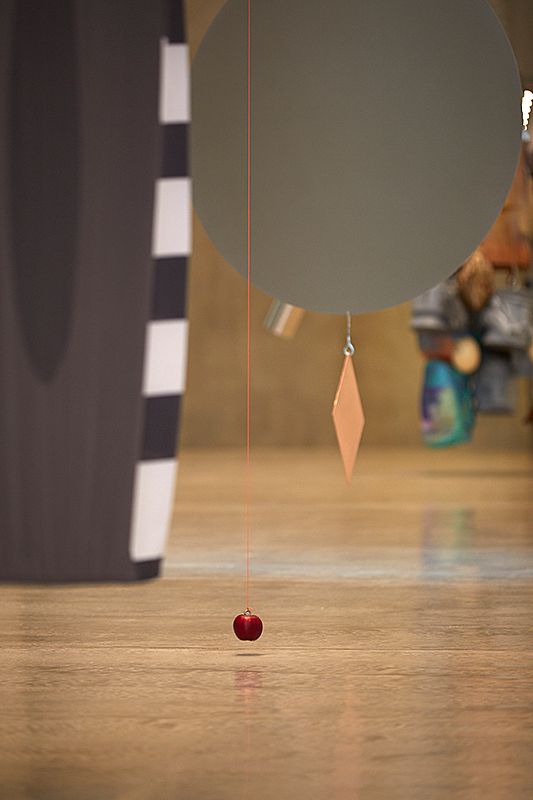

Earthcraft is made up of nine sculptural elements, like the nine (according to some) planets in the solar system. Dwyer’s system includes the iceberg, a plumb bob, a stainless-steel Möbius strip, silken banners, an actual apple, a slender mobile, a long pipe, a collection of heads and a silvery sphere – some are found objects, some printed, others shaped by hand or manufactured. Each in turn occupies the centre of the eastern ramp – a wide hallway-space that leads to the upper galleries – so that one is forced to sidle around it awkwardly. A ramp affects one’s movements, experiences and interpretations strangely. Here, choices need to be made about which side of the ramp to walk on, which direction to take, how to negotiate oneself around each component of Dwyer’s installation.

The various parts of Earthcraft seem to accompany those who visit it, following them as they ascend. As modernist architect Le Corbusier (1887–1965) argued, “architectural promenades” force one to follow a kind of itinerary, with various perspectives developed along the way.1 This architectural device shapes how one sees, thinks, moves and proceeds from one object to another, allowing a spatial story to unfold, one that is open-ended and perpetually ambiguous.

Curator Sarah Wall explains in her written introduction that the title Earthcraft comes from eorðcræft, an Old English word for geometry. Many of the objects fabricated by Dwyer for the commission have geometric forms, both two dimensional and three dimensional. There are quadrilaterals, circles, a cylindrical pipe, a sphere. Each feels immediately recognisable and graspable. Pure geometry’s mathematical concern with the properties of space, in terms of plane and solid figures, is evident in the forms.2 The shiny plumb bob, an instrument of measure, hangs suspended from an orange cord, producing a fine vertical reference line. Like the inclined plane of the ramp, it references the force of gravity, showing that Earthcraft concerns itself with mass, weight and physics as well as geometrical operations such as measurement, translation, rotation and reflection.

The various parts of Earthcraft seem to accompany those who visit it ... To view the sculpted works is to simultaneously see a novel version of oneself looking back.

Indeed, it is via the reflective properties of stainless steel that Dwyer’s work begins to interfere with the purity of geometry and enact a site-specificity. As if Len Lye Centre architect Andrew Patterson’s rippling, mirrored façade has continued inside, one sees oneself reflected in Dwyer’s manufactured forms: distorted and tiny in the plumb bob; wavery and unstable in the Möbius strip; momentarily flashing upon the rotating squares; attenuated in the long pipe; and rendered both squat and stretched in the final sphere. To view the sculpted works is to simultaneously see a novel version of oneself looking back, alongside fellow gallery visitors, the surrounding built environment and lighting both natural and artificial. This reflection undermines and complicates the geometric forms – they absorb, distort and re-present everything and everyone around them.

Dwyer seems unafraid of these inevitable distortions. Her Möbius strip, that ‘impossible’ construct usually captured in two-dimensional drawings, finds its form in a wide, silvery, bent band. Hanging from the ceiling, slowly rotating back and forth, it seems to call to Len Lye’s Universe (1963–76) in the next room. Just as Lye found local collaborators to assist him to push the limits of engineering for his sculptures, Dwyer used Taranaki fabricators Global Stainless Industrial (who have also worked for London-based artist Anish Kapoor) to create her multivalent stainless-steel forms. An iPhone has been attached to the underside of the Möbius strip – it plays drone footage of the Len Lye Centre’s mind-bending façade as well as of the very ramp one walks upon. The categories of ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ are thereby confused. As the phone spins around, one can see the small logo that anticipates the fifth element of the installation, a shiny red apple.

Like the plumb bob, Dwyer’s apple is suspended from an orange cord. It reminds us that it was the soft thud of fruit falling from a tree that led English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton (1643–1727) to devise his theory of gravity. However, this apple never completely falls – it floats, continuously defying gravity, the principle it is supposed to demonstrate. The frozen moment draws attention to how, in Earthcraft (which also offers a linear progression from unit to unit), things freeze. They get stuck. Certain elements may be skipped or revisited. Absorbing the exhibition involves not a measured march but a wandering negotiation.

Blissfully, one is encouraged to walk amongst the tall banners that fall in between the Möbius and the apple. It is eerie to pass through the great drops of fluid fabric. Self-conscious, I take my time and hold my breath. The banners flutter in response to movement and for a spell completely fill my peripheral vision. Each of the textiles is a grand, dramatic standard for who knows what. One banner is brightly coloured (high-key blue, red and yellow together with green, mauve, purple, pink, grey and black), while the other is not, creating an odd dualism for visitors brave enough to traverse them. Together, they are like modernist theatrical productions for a Shakespearean history play, or the set design from a medieval film in technicolour. In the shapes on her banners, Dwyer demonstrates that geometric forms become symbols when taken a little further. A sphere becomes an apple or a head. A triangle becomes the pediment of a temple. A cylinder becomes a snake. A circle is a sun.

On the black, white and grey banner, another circle becomes a giant eye with triangles for eyelashes and raindrop-shaped tears. There are congruencies here with Wharehoka Smith’s Kūreitanga II. IV. (2016), a kōwhaiwhai in acrylic and gypsum commissioned for the gallery’s nearby learning centre.3 Smith’s painting depicts the water cycle as described in a Taranaki karakia that was gifted to him: “It is like… snow from the sky, / Rain from the sky, light showers from the sky.”4 I can’t help but see a mirroring between this work and the Earthcraft banner. Where Dwyer’s giant eye is crowned with thorn-like lashes and drips large tears, Smith has painted sharp rayonnant triangles that make up diamond-shaped eyes. His long strips in contrasting colours – bronze, grey, black – his elongated parallelograms and his mirrored meanders also delight in the playful operations of geometry. Both works dedicate themselves to activating the vertical tension between above and below, ceiling and sky, floor and ground.

Dwyer revisits the way in which modernist artists frequently ascribed mystical meanings to simple geometric forms.

Dwyer’s banners – or flags, as they are sometimes called – hark back to her earlier wall paintings such as Spell for a Corner (2012) and Spell for Sunday (2013). Whereas the textile works in Earthcraft contain fundamental shapes that could have been taken from Bauhaus tutor Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925), Dwyer has in the past directly referred to or paid “pagan tribute” to the work of 20th-century Australian artists such as Sidney Nolan, Sunday Reed and Margo Lewers.5 The geometric idea of translation creeps in again here as Dwyer revisits the way in which modernist artists frequently ascribed mystical meanings to simple geometric forms. These artists often used geometrical figures to create quaint visions of the future or futuristic visions of the past, so Dwyer’s engagement with these visual histories introduces an additional layer of temporal complexity. In his performance Karawane (1916), for instance, the German Dadaist Hugo Ball used a cylinder to stand in for a sorcerer’s hat; and in the 1940s Nolan used a black square to stand in for the outlaw Ned Kelly’s helmet. Dwyer referenced both of these in her 2010 performance Captain Thunderbolt’s Sisters – though that work is a contemporary/modernist retelling of a colonial story, whereas the colourful banner in Earthcraft has a medieval yet 20th-century flavour. Extending this combination of artistic eras further, the simple rhombus-shaped pieces of stainless steel that make up Dwyer’s body-sized mobile could be read as the abstracted patches of a 16th-century Harlequin costume.

After this mobile, which glints as it turns, is a long stainless-steel pipe on a dynamic diagonal. A replica of the tall steel drainpipe in the far corner of the East Ramp, its surface is shiny and outer-spacey. Placed not far from the zero-gravity apple, the pipe makes me think of the spinning bone in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which is tossed into the sky and then graphically matched to become a spaceship. My invocation of the history of cinema and science fiction is deliberate: Earthcraft is certainly not straight minimalist sculpture nor merely a lesson in geometry. As a quest it is far from straightforward; as an artwork it operates in a complex spatio-temporal and fictive way.

The relationship between science fiction and contemporary art has been masterfully explored by Australian art historian Amelia Barikin. Barikin argues that some works of art embody, materialise or enact the operating systems of science fiction.6 Just as Dwyer demonstrates the operations of geometry, she can be said to call on the “core principles of science fiction” (in Barikin’s words), such as “alternate temporalities, extrapolations, speculation, consciousness of mutability, imagined possibilities”. For Barikin “sci-fi as a mode of thought” and “a mode of making” is a now-constant presence in contemporary art.7 It is perhaps part of the broader artistic project described by art historian David Joselit that draws on “a reservoir of alternative image worlds … escapist fantasies or radical political utopias”.8

Earthcraft also shows traces of the illusory art of special effects – Dwyer has even described herself as “just the props person”, rather than an accomplished sculptor.9 It was in fact a prop-maker for fantasy films who first introduced her to the particular kind of plastic from which she crafted the crystalline iceberg.10 To work the material into shape the artist must heat it with a hot-air gun and – in a very bodily process – wrestle it into shape as it welds to itself.

There is definitely something of the studio backlot to the eighth part of Earthcraft, a cluster of heads and figures gathered together and strung from above. The most predominant head is a bronze one in the form of a large Rapa Nui moai – monumental ancestors carved in volcanic rock more than 500 years ago – with a second, smaller moai below, varicoloured in purples, turquoise, greens and grey and with an extra eye painted on its neck. Bizarrely, tangled together with the moai forms are helmets, whole droids from the Star Wars film franchise, ostrich eggs painted with eyes – alongside an elephant, a turtle, a Madonna, a bone and a strange head-shaped conglomerate that seems to have been crafted from a string bag, ceramics and coins. Some of the cast-plastic heads, helmets and figures have been encrusted with semi-precious jewels; the turtle’s shell is covered with stones.

Dwyer’s use of the Rapa Nui moai form is misguided.

Each of these objects is replete with narratives that offer a cacophony of cultural and religious meanings. They could have been taken from the sets of different films: a sci-fi fantasy, a revisionist historical epic, a Paci-flick. Together they make up an incongruous bunch, as though they’re in temporary storage. The hanging mechanisms are strong and unforgiving, taut metal wires and industrial chains and clasps bolt firmly into the tops of heads. It’s almost like Dwyer has acted as a contemporary Queequeg and in the process constructed an eccentric collection of hunting trophies, a charm bracelet of odd taxonomies.

This daunting assemblage also recalls the wall-necklaces that Dwyer has exhibited previously. Works like Methylated Spiritual (2012) are sculptures strung across galleries, from which hang a variety of objects – her dead mother’s whiskey bottle, coloured plastic shapes, crude ceramics and found miscellany. Throughout her practice Dwyer has often dangled ‘stuff’ from bijou-like chains – she has reflected on how one series of necklaces was made after the death of her mother, modernist jeweller Dorothy Dwyer (née Ellen Dorothy Bjorn).11 The head-cluster in Earthcraft could be considered what Melbourne-based art historian Helen Hughes calls one of Dwyer’s “earrings for ceilings”.12 In an act of metonymy, such pieces imply the existence of a wearer – suggesting a figure who is absent or that the gallery itself is a body. Conventionally, necklaces and earrings adorn collarbones and earlobes, but who, exactly, might this jewellery belong to?

In fact, it is the activation of head and neck in the eighth component of Earthcraft that is the most problematic aspect of this commission. Dwyer’s use of the Rapa Nui moai form is misguided. The fact that her ‘replicas’ are suspended from holes drilled into the head, an area of the body sacred to the Rapa Nui people who created moai, is particularly insensitive. Perhaps this is a flirtation with the “future primitive” – the title of an exhibition at the Heide Museum of Modern Art in 2013 that included works by Dwyer. Yet as Andrew McNamara and Ann Stephen point out in the catalogue for that show, “there are no primitives”. Primitive is a “term of denigration” foisted upon one people by another and primitivism in art “resides on the knife edge of envy and denunciation”, involving “the projection of alternate imaginative horizons and the worst forms of cultural and racial chauvinism”.13 On this very platform, in relation to work by Francis Upritchard, Lana Lopesi has articulated the politics of such “professional borrowing”: the “abstracted violence”, the insensitivity involved in such acts of orientalising “white imagination” when artists neglect to acknowledge where culturally specific objects have been appropriated from.14

Artists like Dwyer and Upritchard do not so much step outside of cultural parameters as stay safely inside their own, whilst carelessly absorbing past and present symbols, objects and land that that belong to someone else.

A broader phenomenon might be at play here, what Polish philosopher Leszek Kołakowski has called a desire or ambition to step outside familiar cultural parameters in order “to grasp what is culturally foreign”, warning that to do so involves genuine risk.15 Then again, perhaps the Pākehā and white/settler Australian practice of misappropriating things is an inherent part of these cultures, formed as they were by colonialism. In these terms, artists like Dwyer and Upritchard do not so much step outside of cultural parameters as stay safely inside their own, whilst carelessly absorbing past and present symbols, objects and land that that belong to someone else.

Helen Hughes has a similar hypothesis that is also presented in the Future Primitive catalogue. She argues that works like Earthcraft perform “a kind of time travel – moving backwards and forwards between past and future, constructing alternative or speculative histories”.16 Contemporary art – by its nature “hostile to closure” and open to states of potential – becomes a site for revisiting histories as well as proposing alternative futures. Hughes goes on to describe how certain contemporary artists are preoccupied with “fictional rituals, myths and discarded relics and the specific temporality produced by such works”. In being thus preoccupied, they attempt to make and remake what she calls “fluid histories”.

Why is such a methodology so common? Hughes argues that in Australia this is because “the present takes the form of a palimpsest over which white national history can be written and revised ad infinitum: because, of course, the structure of the palimpsest is a mirror of the constitutive policy of Australia, terra nullius, that has officially and unofficially undergirded Australian politics ever since white settlement in 1788”. So-called history has already been fabricated many times, so why shouldn’t artists fabricate it some more? White Australians are already adept at living with “co-existing and internally fractious histories”, Hughes says, so that artists like Dwyer often present works in a “flexible present”. In this way, Australia’s multiple and conflicting histories cannot help but inform contemporary Australian art.

Even physicists like Newton were seduced by the occult – and modernism itself was particularly cultish.

Hughes’ point that contemporary artworks in the present look backwards and forwards in time, and in doing so construct alternative histories, is certainly pertinent to Dwyer’s Earthcraft. At first blush the work seems to represent a linear progression, an image promenade that moves in increments from unit to sculpted unit. Parts can even be read as stand-ins for various epochs: the ice age, the iron age, the bronze age, the Anthropocene and – with the final, impermeable silver sphere – a sort of cold and mechanical future. Yet this straightforward, positivist account is undermined by Dwyer’s installation. Geological eras are challenged by the presence of a plastic iceberg; mathematical forms are contaminated by human presence; reoccurring myths dating back to the Ancient Greeks furnish the narratives of science-fiction cinema. Even physicists like Newton were seduced by the occult – and modernism itself was particularly cultish. Humanity is diverse; it cannot be contained. Each body that visits the eastern ramp – each body that is captured by the surveying security camera reflected in Dwyer’s stainless-steel ball – brings with it its own lived experience.

In Earthcraft, forms made out of materials that are manufactured and unyielding float in enormity beside ones that are fluid, soft, organic, comic and, in the case of the apple, even rotting. Dwyer’s artwork reminds us that, in the words of anthropologist Michael Taussig, there is no such thing as a division between dead objects on one side and lively humans on the other.17 This is why the inclusion of the moai is so fraught: they are much more than mere objects. Humans and things are perpetually coupled – coexisting in the world we are totally dependent on each other and in constant conversation. This is made especially evident when we engage with experiential artworks.

But such works also act as a kind of prosthesis to imagine otherwise, as Barikin argues. It is politically, culturally (and perhaps even spiritually) important for us to experience, if only for a moment, the possibility that “we need not accept the world as it is because we can imagine it – and reshape it – otherwise”. Contemporary art that produces “science fictionality” in real space and real time, unfolding amongst durations and spaces and materials, is in fact producing a recognisable sensation: “a kind of sensual, vertiginous pleasure invoked by the opening of a chasm, the creation of a hole through which another reality might emerge”. Perhaps it is such a sensation, a rift within the familiar world, that is generated by Dwyer’s Earthcraft. Yet there remains just enough of the fabric of our own reality to make this experience troubling.

With thanks to Lana Lopesi, Kelly Loney, Sarah Wall and Anna Hodge.

1Quoted in David Joselit, After Art (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2013), 46–48.

2“Geometry”, in The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide, ed. Helicon (Helicon, 2018).

3Kūreitanga II. IV., ed. Paul Brobbel (New Plymouth: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre, 2019).

4“Pērā Hoki”, trans. Ruakere Hond, in Kūreitanga II. IV., ed. Brobbel, 3.

5Linda Michael, “Future Primitive”, in Future Primitive, ed. Linda Michael (Melbourne: Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2013), 23.

6Amelia Barikin, “Introduction: Making worlds in art and science fiction”, in Making Worlds: Art and Science Fiction, eds. Amelia Barikin and Helen Hughes (Melbourne: Surpllus, 2013), 7–13.

7Ibid.

8Joselit, 90.

9“Mikala Dwyer Interviewed by Robert Leonard”, in Mikala Dwyer: Drawing Down the Moon, ed. Evie Franzidis (Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 2014), 57.

10“Mikala Dwyer Interviewed by Robert Leonard”, in Mikala Dwyer: Drawing Down the Moon, ed. Franzidis, 61.

11Ibid.

12Helen Hughes, “Inheritance: Jewellery and the sculpture of Mikala Dwyer”, in Mikala Dwyer: A Shape of Thought (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2018), 20–25.

13Andrew McNamara and Ann Stephen, “The Double Risk of Primitivism”, in Future Primitive, ed. Linda Michael (Melbourne: Heide Museum of Moderm Art, 2013), 29–44.

14Lana Lopesi, “The Moral Argument: A Review of ‘Jealous Saboteurs’”, The Pantograph Punch, 18 October, 2017, www.pantograph-punch.com/post/review-jealous-saboteurs

15McNamara and Stephen, 35.

16Helen Hughes, “The Future, Presently”, in Future Primitive, ed. Michael, 85–96.

17Michael Taussig, “Art and Magic and Real Magic”, in Mikala Dwyer: Drawing Down the Moon, ed. Franzidis, 25–29.

Earthcraft

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

6 Apr 2019 — Ongoing

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.

Photographs: Sam Hartnett, courtesy of the artist and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre.