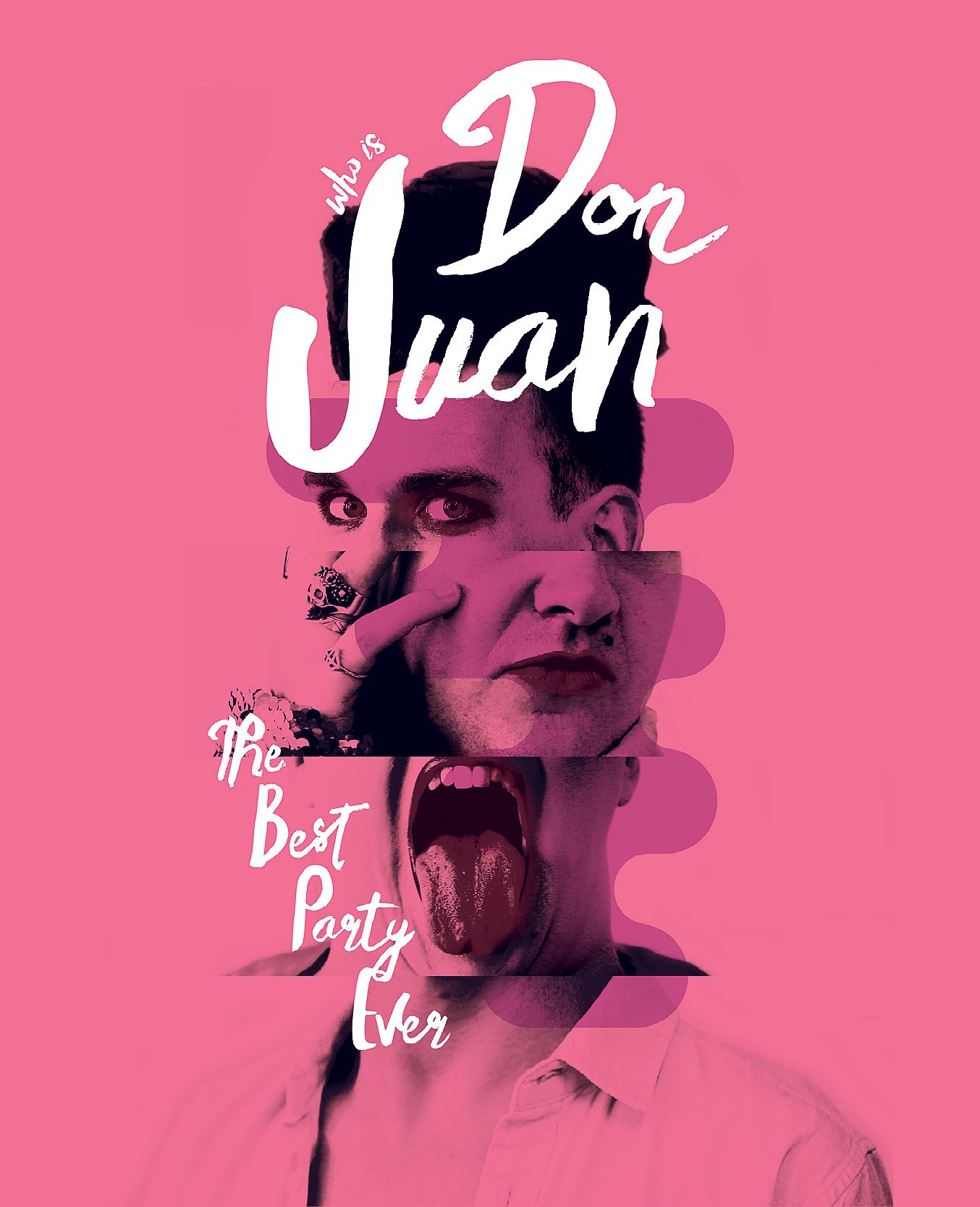

Review: Don Juan

Adam Goodall reviews A Slightly Isolated Dog's Don Juan.

The way people tell it, around half of the young artists making theatre in Wellington are influenced in some way by Leo Gene Peters. As a freelance director and the creative force behind A Slightly Isolated Dog, Peters has been one of the key figures in the local independent scene’s push towards a cinematic, experiential theatre, one that freely twists and abandons conventional structure in order to open itself up to its audience. His language, emphatically non-naturalistic and grounded in the collective weight of the ensemble, can be traced through some of Wellington’s most interesting companies: your my accomplices, your Bright Orange Walls, your Long Clouds. (It’s perhaps not a surprise that reviewers less enamoured with this style have levelled the same criticism at all these companies: their shows feel like insular parties, shows for those ‘in on the joke’.)

Part of the reason for this is that, like most directors in this tiny city, Peters frequently works with young theatre-makers. Those collaborators end up refracting his sensibility back into the world, an industry of funhouse mirrors. I note here that even I’m one of them: Peters directed my first script, Deadlines, back in 2012 as part of the Young & Hungry Festival of New Works, and I still draw from that experience.

I mention all this because Don Juan, like Death and the Dreamlife of Elephants in 2009 and Perfectly Wasted in 2013, feels like a well of ideas that young theatre-makers will be drawing on for the next five years. It feels, more than anything, like a moment.

On one level, Don Juan is a reimagining of Moliere’s Don Juan or The Feast with the Statue, the definitive work about the legendary playboy and his exploits. On another, Don Juan is a play about a play performed by ‘A Slightly Isolated Dog’, a resolutely fictional theatre troupe who speak with ridiculous French accents and dress like John Leguizamo’s collective in Moulin Rouge! The cast of five – Peters alumni Jonathan Price, Andrew Paterson and Maaka Pohatu, and recent Toi grads Comfrey Sanders and Susie Berry – are powerful hosts, open and friendly and driven by their huge emotions.

All that said, the first level, the Moliere reboot, takes a while to come into being. We’re first run through an extended prologue in which the troupe weaves together localised tall tales and actual story, building Don Juan up like he’s a VIP at a humble flatwarming. The prologue pokes at big ideas about myth and escapism, but it’s meandering and a little bit frustrating; the energy lags a little when they have to drop an anecdote and pick up a new one, and the actors feel a little bit wobbly when they catch themselves ad libbing over each other. Besides, the party don’t start til Don Juan walks in

In a chunky white baseball cap and blue silk scarf, this Don Juan is played by two – one actor his voice, speaking into a microphone, and the other his physical presence, lip-syncing with a portable speaker in hand. This Don Juan is a construct, with a deeper, louder voice and more sensuality than any human being. He’s a fantasy of autonomy without consequences; he’s Beyonce and Kanye, transplanted to the 17th century (connections made by Peters and his cast through electrifying acapella interludes of Partition and Power). Like all Don Juans before him, this Don Juan exists to be celebrated. Look at that golden god. I bet if the rules no longer applied to us, we’d be this outrageous too.

The troupe keeps us in that celebration with outrageous accents, drinks breaks and their own attempts at breaking the rules. They even get us to participate in some of the most compassionate, boundary-respecting audience interaction I’ve been part of. The direct engagement pre-show while in the theatre and the foyer softens us up; the Moulin Rouge!-by-way-of-poor theatre aesthetic builds a formidable anything-goes vibe; and the archetypes we’re dealing with – earnest Philippe, snarky Julie, no-fucks-given Lily, childlike Maurice, flippant Ginger – are clearly delineated right from the top, clarifying the consequences of any interaction. Further, the cast is superb at guiding people through the small roles they play: statues, execution squads, vengeful brothers.

But they also keep us aware that there are actually still rules. Maurice’s excitement at getting a puppy is quickly shut down with reference to ‘what happened last time’, while Philippe’s desperate attempts to woo an audience member are shut down by the troupe, tackling him and shouting their apologies. Don Juan draws us away from celebrating this playboy and asks us to question why we do it; the emphasis is less on telling the fantasy, and more on considering why it’s a fantasy in the first place.

Peters and his team don’t stick the landing as effectively as they could, though. A third-act structural collapse designed to drive the conversation home feels overly workshopped, not to mention reminiscent of a similar tonal shift in the Capital E production Peters recently directed, An Awfully Big Adventure. It’s an effective way to get the stragglers in the audience caught up to the thematic discussion, but it goes off like a sparkler, short and sharp but fizzing out quick. For a show that’s been so audacious and alive up to this point, it’s such an obvious way of blowing up the popsicle stand.

Even with that, though, Don Juan feels like a moment. It’s giddy and exuberant, it impressively iterates on Peters’ frequent motifs and constantly makes brilliant little offers. Like Elephants and Perfectly Wasted, it revels in the spectacular and alluring corners of a generic language while encouraging us to look at the appeal of those corners a little more deeply. If Peters has been pushing all these years to make a non-stop party that’s both fully inclusive of its audience and entirely exclusive to them, Don Juan is the closest he’s gotten. It’s potentially the closest anyone is ever going to get in this city. And I think people are really going to try.

Don Juan plays at Circa Two from 25 April - 23 May.

Tickets available through Circa.