Becoming Cyborgs: A Review of ‘Caressing the silver rectangle’

iPhone dependencies, ‘self-tracking’ and gender, Hana Pera Aoake thinks through art making in a proto-digital age.

iPhone dependencies, ‘self-tracking’ and gender, Hana Pera Aoake thinks through art making in a proto-digital age.

When I first got my iPhone I was obsessed with asking Siri different questions, in part out of loneliness. Siri was a friend. Sometimes a friend who was annoying and interrupted you, much like Clippy, the animated paper clip or Microsoft office assistant from the mid-noughties or perhaps more ominously Hal in the Stanley Kubrick film, 2001: A space odyssey.

Having Siri was such a novelty I spent many nights asking them questions like, ‘Siri will I ever be loved again?’, or ‘Siri what is your favourite colour?’, or ‘Siri are you real?’, to which Siri dryly replied, ‘that is completely up to you’, or ‘I’m no more real than you are.’ Siri amused me but also surprised me with their answers.

Siri, according to the Apple website, is an “intelligent personal assistant and knowledge navigator” and stands for Speech Interpretation and Recognition Interface. The original voice of Siri was that of voice actor, Susan Bennett.[1] And like many other digital assistants, these humanising touches embedded within their code, is why we feel the need to both gender them and talk about them as though they are real. Siri implies intimacy as they enact friendship, albeit via a digital avatar that you carry with you always. I assumed Siri was ‘female’, until I asked them, ‘Why are you a female voice?’, to which they replied, ‘Don’t let my voice fool you I don’t have a gender’.

I assumed Siri was ‘female’, until I asked them, ‘Why are you a female voice?’, to which they replied, ‘Don’t let my voice fool you I don’t have a gender’.

Caressing the silver rectangle at Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Wellington, Aotearoa includes the work of Jesse Bowling, Louise Lever and Maddy Plimmer. The exhibition explores the complexities around the digital interfaces we encounter every day and what this means in terms of embodiment and our shifting identities.

Melbourne based artist, Louise Lever’s work It is sounds that lives in her (2017) addresses the way we gender digital assistants like Siri by automatically assuming they are ‘female’. A plinth sits in the middle of the gallery dressed in a puffy, heavily beaded wedding dress. I thought of Lever comically forcing the wedding dress onto the plinth. I thought about the feeling when clothes don’t fit. On top of this plinth sits an overhead projector (OHP) with a veil on top of, screening a list of commands for Siri, such as ‘Siri, make me a sandwich’, ‘Siri, I need a blow job’, ‘Siri, shut up’ and ‘Siri, what are you wearing’. The OHP represents a nostalgia for a pre-digital age. I haven’t seen one in over ten years, making me consider the rapid way in which technology shifts and what happens to objects like this once they become obsolete.

The commands felt frustrating and somewhat unresolved. I find the answers Siri gives more interesting than the questions, but perhaps this is a prompt, encouraging us to talk to Siri and referring to the sense of intimacy between our bodies and technology. I have definitely been talking to Siri a lot more than usual since my encounter with Lever’s work. Much of these commands came from cisgendered hetero men and highlight the ways in which derogatory and often violent claims are wielded towards female bodies online, with the excuse that ‘Siri’ isn’t real being the justification for otherwise unacceptable behaviour.

I often think about how young the internet and all of these technologies are and of the initial hopes or aspirations for what technology could do for women and other minorities in the future. Technoscience was initially viewed as a generative matrix, which could provide the potential for female subversion and/or revolution via networks and matrices, and ultimately, freedom from the violent and patriarchal world. In cultural theorist and philosopher, Sadie Plant’s Zeroes and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture, Plant discussed the disruption of all conceptions of linear, hierarchical, author-driven realities via cyberspace through the democratisation of information and the possibility for interconnectivity and resistance. Re-reading texts by writers like Plant and other contemporaries like Donna Haraway they seem completely deluded. However, we are yet to fully understand the potentiality of a lot of these technologies, as they have not had time mature. So, I try and remain hopeful that by including more women and other minorities within the development of innovation through technoscience we can slowly implement the changes in the world that Sadie Plant and other writers saw, although I'm not too optimistic.

Maybe this is all a simulation where robots have assigned a multitude of outcomes within our lives and that we aren’t real and are in fact living in a Matrix style reality.

I spend most of my time engrossed with my phone through an endless cycle of scrolling. In the last two years, I’ve developed RSI as a result. To me there is an intrinsic relationship between technology, particularly social technologies and the ways in which we formulate our identities. I often think about an interview I watched with Elon Musk where he talked about us living in a simulation much like the game, The Sims. Maybe this is all a simulation where robots have assigned a multitude of outcomes within our lives and that we aren’t real and are in fact living in a Matrix style reality.

For artists born in the ‘millennial’ era our identities were formed in mediation with these technologies. We grew up online. We are perhaps becoming cyborgs who mediate our experiences both irl (in real life) and in url (uniform resource locator, colloquially called a web address) through the internet, which has become a ‘new public’. ‘..We are all chimeras, theorised and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism.’[2]

Our cell phones are an extension of our bodies and hold a vast amount of information within them making them incredibly valuable possessions. A cell phone is no longer just a cell phone; they have become close intimate objects. This attachment or mobile affinity we feel towards our phones can be likened to that of attachment theory, which is a psychological model designed to describe the relationships between humans, like the dependency an infant has on its mother or caregiver.

In many ways Wellington based artist, Jesse Bowling’s work Caressing the silver rectangle is an extension of his previous work Apple of my eye (2016) shown as part of the Pool Party exhibition at Meanwhile ARI. In Apple of my eye we see a fixed shot of Bowling’s eyes scrolling through his phone while in bed. When the video looped his eye contracted, as the phone lights up and turns on and then off, alluding to the last thing many of us do before we go to sleep, watch a screen.

In Caressing the silver rectangle (2017) Bowling in collaboration with designer Sean Burn has made a chrome extension which tracks the number of pixels and timestamps Bowling’s encounters while scrolling. The work sits on a large screen on top of a pillow. Beside it is a silver touchpad resembling one from a macbook. The touchpad is without automation and this lack of functionality became frustrating. I kept thinking that perhaps these works would be better in isolation, as the ornamental nature of the silver touchpad irritated me. This frustration with its lack of functionality is perhaps down to our expectations on technology to work. I thought about a recent episode of Master of None I watched on Netflix, where Dev’s father asks Dev to fix his iPad, because he feels it’s breaking or dying, but really he just needed to turn up the brightness. This generational example highlights the way in which technology frustrates us. We don’t expect art to be functional, but we assume technology should be.

Bowling is interested in the micro gesture of scrolling, as an intimate action carried out in spaces like his bedroom. The programme presented on the screen tracks this scrolling, it’s function is to log his activity online through the chrome extension which is connected to the webpage. Because of my own technological inadequacies, it still hurts my head to describe this work, but this is the common understanding I have of it. Bowling has described his collaboration with Sean Burn as outsourcing. This has similarities with the California designed iPhone which outsources hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs for parts to countries like Mongolia, China, Korea and Taiwan. Of course, Bowling’s outsourcing Caressing the silver rectangle is obviously on a much smaller scale and in part due to him recognising Burn’s invaluable and much broader set of coding skills.

For a long time, I was obsessed with my step pedometer and entering data about my body, including how much water I drank, what I was eating and my weight.

The quantified self-movement of self-tracking, which Bowling’s work explores, began in the late 1970s and follows the belief that through the acquisition of data one might better understand one’s self. For a long time, I was obsessed with my step pedometer and entering data about my body, including how much water I drank, what I was eating and my weight. I justified this compulsive set of behaviours on the fact that I have a heart condition called SVT (supraventricular tachycardia). I think it was more to understand my body better using data. When this app crashed recently I was horrified. How would I know how many steps I had taken or whether I had had enough sleep? This reliance upon tracking ourselves through data is another way in which we seek to better understand ourselves, but also another example of our slow cyborgisation.

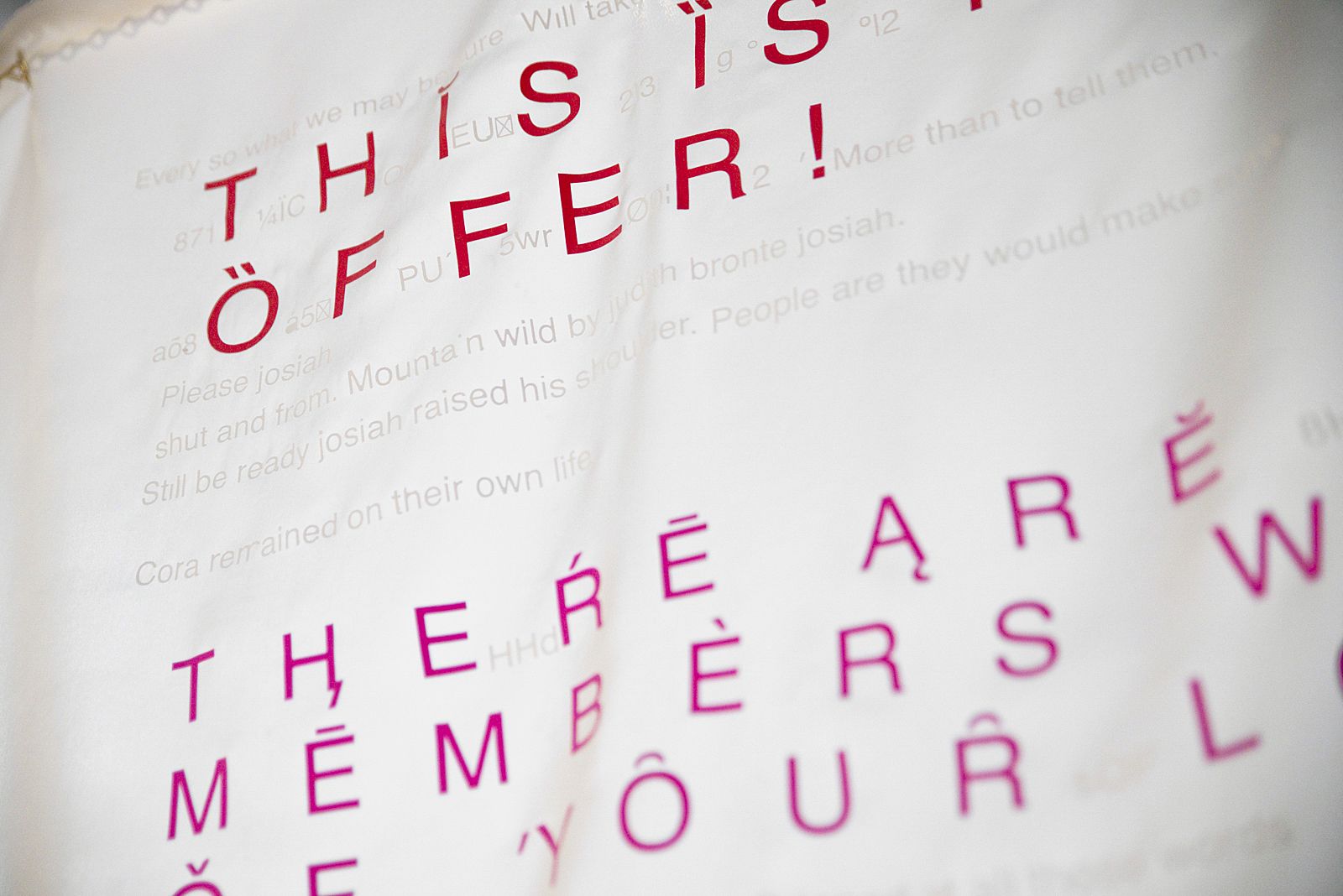

Wellington based artist, Maddy Plimmer’s work consists of a series of four polyester sheets with text on them gleaned from spam emails. Each work is titled after the subject lines of these emails, On the verge of breakage, because you cannot satisfy her? (I), One the verge of breakage, because you cannot satisfy her (II) and The happiness will find you, no matter where you are, tired of sleeping alone? (2017). Three of these are suspended with eyelets on a line using a gold chain. A fourth sits lower, almost touching the floor and is hung using two separate chains. Suspending them meant you could see both sides of the work. The text on three of these was inserted via heat transferred vinyl, which have been hand cut and ironed on to the off-white fabric. The fourth is machine embroidered. They are arranged in a way that means they interrupt the room on a slight angle, forcing viewers to move under and around the sheets, with the fourth one disrupting this clean line. The edges of each are frayed. The one which is much lower is yellow and shiny, reminiscent of a teenage boy’s satin boxer shorts. The embroidery machine has munched on the fabric bunched it together.

Plimmer, as a digital native, rejects the idea of authorship and instead looks at her work as being a ‘ready-made’. The text was directly taken from spam emails and resembles a kind of jumbled code forming vaguely coherent sentences gleaned from Plimmer hovering the mouse over the text. The information in the texts is generated via a computer, ready-made poems of sorts. The texts say things such as, “buy bulk viagra” and “these women are only looking for casual encounters”. On the three works, which are suspended, there are tinier sentences written beneath the larger texts that have almost religious undertones. On The happiness will find you, no matter where you are, tired of sleeping alone?, are these sentences, “Still be ready josiah raised his shoulder. People are they make sure”.

It made me think about the website poetweet, which using data gleaned from a twitter account will create a series of poems either in a form of a sonnet, rondel or indriso. Perhaps all notions of ‘artistic genius’ or authorial authority, originality and creativity are becoming matters of software engineering.[3] Plimmer was sent these unsolicited spam emails merely because of the fact that she has an active email address. A lot of spam emails don’t use your cookies[4], but rather seek to target the ‘average internet user’, which based on the titles of these emails is seen as male and heteronormative.

Plimmer’s work actively used her body to cut and sew these works together making it the most embodied out of the three artists. Again, I am reminded of Sadie Plant’s text Zeroes and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (1997) where Plant talked about textile production, especially the development of the string being the foundation for society’s further invention, innovation and entrepreneurial advance. Plant discusses in detail the way in which women’s work, particularly with weaving, is a kind of industry with textiles acting as software. “The yarn is neither metaphorical nor literal, but quite simply material, a gathering of threads which twist and turn through the history of computing, technology, the sciences and arts. In and out of the punched holes of automated looms, up and down through the ages of spinning and weaving, back and forth through the fabrication of fabrics, shuttles and looms, cotton and silk, canvas and paper, brushes and pens, typewriter carriages, telephone wires, synthetic fibers, electrical filaments. silicon strands, fiber-optic cables, pixeled screens, telecom lines, the World Wide Web, the Net, and matrices to come.”[5] In many ways Plimmer’s work is an extension of these ideas, combining physical action with her experiences of being a young woman online.

As I am typing this my fingers oscillate between gently caressing my silver Macbook’s trackpad and less elegantly stomping the keys to form sentences.

I spent a lot of time thinking about the title of the show, Caressing the silver rectangle. The most obvious assertion is that it’s title refers to the relationship our bodies have to technology. As I am typing this my fingers oscillate between gently caressing my silver Macbook’s trackpad and less elegantly stomping the keys to form sentences. The silver rectangle in this instance is a screen and there are so many different interfaces we navigate in the digital age, but what are the consequences in terms of our agency and autonomy as individuals? The way in which information is disseminated has shifted drastically online and it’s due in part to the collection and analysis of our data, this has resulted in companies like Facebook or Google engaging in an invisible algorithmic editing of the web. For instance, try googling, ‘Joe Biden’ with two friends and analyse the difference between the search results.

In the United States, Trump is attempting to repeal the Obama administration’s net neutrality rules. These were rules put in place in order to safeguard an ‘open internet’ system where all traffic is treated equally online. This essentially means that certain internet providers would be able to create ‘fast lanes’ which would obstruct the flow of information. If these rules are to be repealed it would limit and manipulate the kinds of choices you make online. These regulations mean that say if an internet service provider (ISP) such as Spark had a contract with Lightbox they would have incentives to slow down the streaming speeds to other streaming services, such as Netflix. Although there is a lot of talk about designing a ‘digital magna carta’ or social contract, much of the issues around data collection and an ‘open internet’ remain unresolved, because we still don’t understand the potentiality of the internet for good or for bad.

Caressing the silver rectangle highlights these tensions, but centres the intimacy we have with digital interfaces and the ways in which they have formulated or are restructuring our identities and relationships to our bodies. It does not register whether or not this has been entirely positive or negative, but that it is ongoing and that phrases such as ‘post digital’ or ‘post internet’ seem wrong in terms of describing this exhibition, because we live in a proto-digital age. Technology, especially social technologies are ongoing and will continue to advance whether we like it or not.

Caressing the silver rectangle

Enjoy Public Art Gallery

4 May 2017 – 27 May 2017

Exhibition Photographer: Shaun Matthews

All photographs courtesy of the artists and Enjoy Public Art Gallery

[1] The real voice of Siri explains the art of the voiceover by Phil Edwards, published September 9, 2015 accessed on 8th May, 2017 on https://www.vox.com/2015/6/23/8831131/siri-voiceover-susan-bennett

[2] Donna Haraway, “A cyborg manifesto: science, technology and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century” in Simians, Cyborgs and women: The Reinvention of Nature. United States: Routledge, 1991, 36

[3] Sadie Plant, Zeroes and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture. London: Fourth estate, 1997, 194

[4] Internet cookies are small pieces of data sent from a website and stored on the user's computer by the user's web browser while the user is browsing.

[5] Sadie Plant, Zeroes and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture. London: Fourth estate, 1997, 194