Uneasy Seas: Attraction and Auē

Jessie Bray Sharpin on two debut novels that reckon with painful memories and fractured families: Attraction by Ruby Porter and Auē by Becky Manawatu.

Jessie Bray Sharpin on two debut novels that reckon with painful memories and fractured families: Attraction by Ruby Porter and Auē by Becky Manawatu.

A broken corrugated-iron bach on sloping dry grass in front of an empty beach. The sound of your dad’s jandals on the concrete path with sand grinding under at each step. Playing with your cousins in a boat made from a washed-up mussel buoy cut in half. Raiding your aunty’s fridge for eggs and old meat to feed the eels at the creek in the estuary when the tide is out. Dark pink strands in your togs, dried fallings from one of two pōhutakawa trees that framed the bach like two flaming beacons, always visible from out at sea in your uncle’s dinghy.

Memories of water. Of place. Of salt and wind.

Ruby Porter and Becky Manawatu, in their respective debut novels Attraction and Auē, echo one another in their portrayal of distinctly New Zealand memories. Through reading both, I was confronted with my own memories of summers, the coast, and small-town New Zealand. Endless family road trips and grief for lost family members.

Attraction is narrated by a young woman on a journey with two friends between Auckland, Levin and Whāngārā. We follow the road trip through the eyes of this young woman, in the back seat with her dog Bo, as her view out the window is translated to the reader via short bursts of memory: of childhood, of her mothers, of her relationship with her ex-boyfriend, and of stories told to her by her te reo teacher Pita of the experiences of his tūpuna in the New Zealand Wars. She is painfully aware of the effects of colonisation, everywhere, and is self-conscious about her place on the land. Her friend Ashi tells her, “Your white guilt isn’t helping anyone,” and the reader breathes out, Ashi providing an alternative to the weight of the main character’s constant guilt.

It is tense and violent, punctuated with scenes of intense familial love – a current that runs through the whole book.

Auē centres on two recently orphaned brothers, Taukiri and Ārama, and begins with Tauk leaving a younger Āri with their aunt and uncle and heading off on his own to Wellington. We alternate between the brothers’ points of view throughout the book, with yet another story woven through: that of Jade and Toko. Jade and Toko’s story, as told by Jade and including stories from her childhood, is set in the world of an unnamed gang. It is tense and violent, punctuated with scenes of intense familial love – a current that runs through the whole book. I think of this aspect of the book differently now, having read Becky Manawatu’s devastatingly moving essay published on Newsroom earlier this month. In it, she mourns the loss (and hopes for the revival) of a relationship with one of her older sisters, who married a gang member. She writes about a red and black wedding dress and I immediately think of Jade. Becky’s writing in this essay, missing her older sister, reminded me of Āri pining for Taukiri. When she talks about the murder of her cousin and childhood friend, Glen Bo, and laments her family being split up and changed forever, I see more of Āri’s pain in Auē.

These traces of a writer’s life that make it into their fiction is something I find fascinating. People write what they know, but they are also writing fiction. The back and forth between the two intrigues me, the discovering of links that a reader may not have known existed. Maybe it started back when I realised that the main character in one of my favourite childhood books, The World Around the Corner (a red-headed girl with glasses) bore a striking resemblance to author Maurice Gee’s own daughter.

We want to know everything, and with fiction, we can’t.

When I chaired a session with Becky and Ruby as part of Verb Festival recently, I asked them about this fiction versus ‘real life’ question. This is why we go and hear writers talk, right? Because it’s satisfying and funny to hear that Ruby Porter, like her narrator, knows Levin like the back of her hand, because she was forced to spend every holiday there as a child. And that she wrote stories as a kid, and they were all set in Levin. It’s interesting when we learn that Becky grew up on the West Coast of the South Island, but that Kaikoura, where much of Auē is set, is where her husband grew up and where she has subsequently spent a huge amount of time.

And yet, and yet, it also infuriates me when young women who write fiction are assumed to be writing barely disguised autobiographies. Particularly in the genre recently dubbed ‘millenial fiction’, which Attraction could fall into. But I think we all do this to some extent. And I know I’ve been guilty (while reading Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends, for example) of assuming that views held by a main character are those held by an author. Sometimes it is accidental association while reading, sometimes it is curiosity. How much has a writer poured their own experiences into their work, how much is imagination? We want to know everything, and with fiction, we can’t.

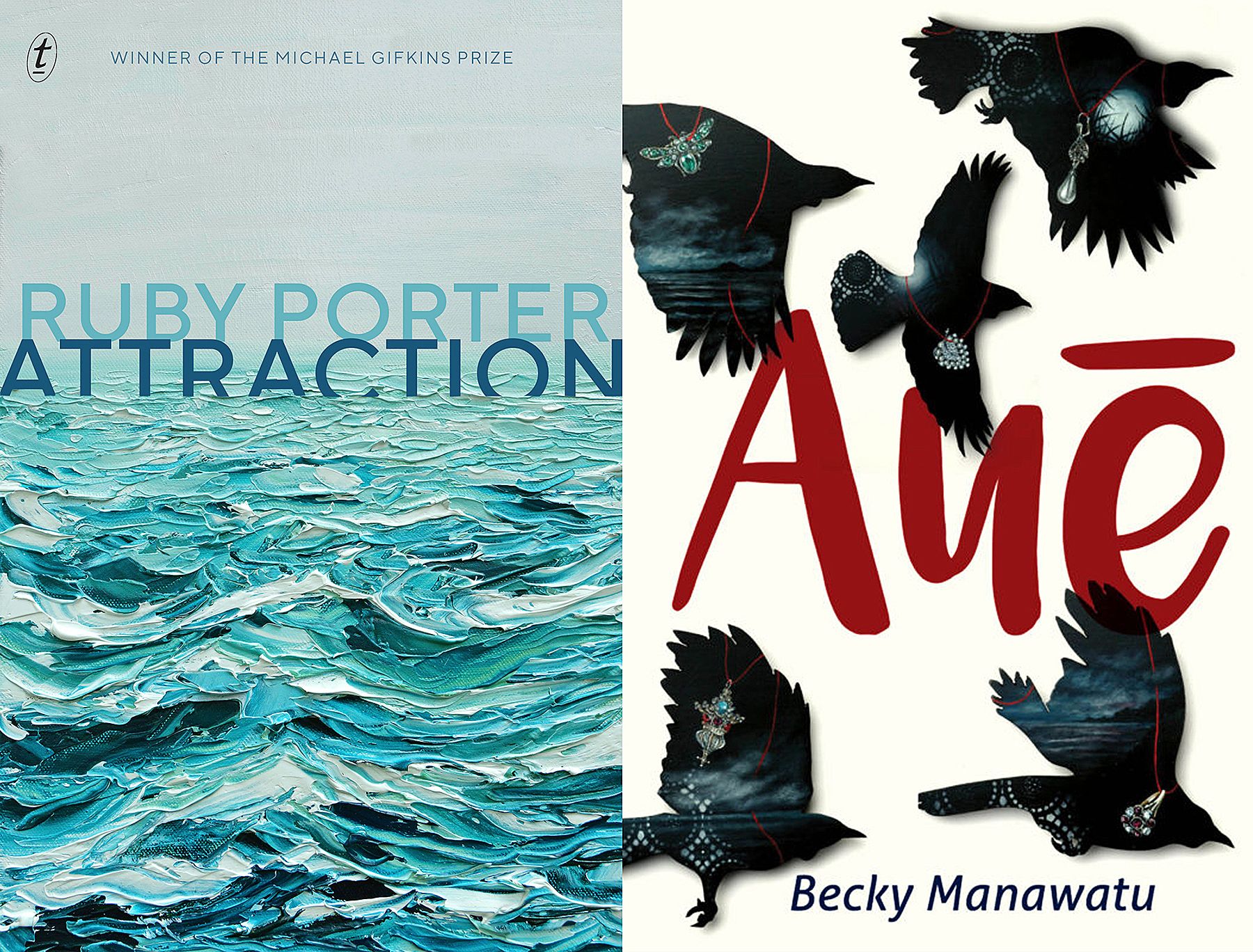

The sea features heavily in these books. Even the cover of Attraction is sea-focused: thick, swimmable layers of blue and white paint make a choppy, familiar ocean. The narrator has a conflicted relationship with the sea. She and her friends go and stay at her family’s bach in Whāngārā. She feels a sense of unease the entire time as she wonders how the bach entered her family’s ownership; thinks constantly about the fact that they are on Māori land.

The three’s-a-crowd tension of the entire book is condensed here in the shallows of the sea, in front of the bach at Whāngārā.

During a phone call on the beach, her mother warns her about swimming in the sea, insisting that she mustn’t go out as far as her friends because she isn’t a strong swimmer. There’s a scene in the book where the narrator does get into trouble swimming – and in our conversation at Verb, discussing this scene, Ruby noted the irony of a Pākehā woman struggling in the water off a Māori beach. Being literally out of her depth epitomises the narrator’s discomfort with the situation she is in: with her family and inherited colonial guilt, with their physical place on the land at that time, and with her feeling of (somewhat self-inflicted) isolation throughout the trip.

For me, the more poignant encounter with the sea in Attraction comes earlier in that same scene, before the main character gets into trouble in the water. I felt in my gut her sense of exclusion and loneliness when she watches the two other women in the water – a casual touch on an arm, the camaraderie of battling larger waves together. The narrator remains apart from them, in her mother’s own definition of her as a weaker swimmer. The three’s-a-crowd tension of the entire book is condensed here in the shallows of the sea, in front of the bach at Whāngārā.

In Auē the sea plays a more prominent role, particularly for Taukiri. He is a surfer who has been betrayed by the sea. He is completely mourning his absence from the water, but is also terrified and angry with it for what it’s done to him. At one point, tripping out on drugs, Tauk begins to think that the young woman talking to him is the sea itself:

‘You must feel very lonely.’ And her voice echoed, and bounced off the walls like she was tricking me, and actually she was the sea, in human form, come to see for herself the pain she caused me. The freckle on her eye starfished out and the sun began to move over her face like it does below the surface of water.

The woman is being caring, but upsetting him with her probing questions, and this love/hate confusion reflects Taukiri’s feelings about the ocean. Tauk’s identity is so tied up with the sea that his isolation and loss of self are directly related to his dissociation from the sea. His new acquaintances in Wellington begin to mock him for having a surfboard tied to the roof of his car but never going surfing, saying that it’s just for show.

Taukiri’s life is bound up tightly in his memories of the sea, both good and bad. I feel like this is representative of so many New Zealanders. The sea is so close to us, always. And those who didn’t grow up here had to come over sea to reach our tiny islands. Attraction and Auē brought up feelings of waterlogged nostalgia that have stayed with me. I’m looking forward to finding out where these writers will take us next.

Auē is published by Mākaro Press (August 2019)

Attraction is published by Text Publishing (May 2019)