Capitalism + Cyborgs: Imagining Change in Time of Crisis

The world is in crisis. Capitalism has failed. Maybe Capitalism's bastard child, the Cyborg, could help us at this time, wonders Anisha Sankar.

Amidst the global pandemic, I find myself stuck between a looming workload and quiet despair at the inability of the world to deal with shocks to its system. The stuckness comes from uncertainty: where to from here?

I begin to think that when nothing is certain, one of our strongest tools might be finding ways to reinterpret and reimagine our relationship to the world around us. I think of the way that science fiction, for example, offers us worlds beyond our material possibilities, sometimes giving form to vague dreams about the end of capitalism.

We might think of this kind of speculation as a rope dropped down into a cave; a tentative offering of something to help us feel our way through the dark. An aid that could help us see without the clarity of our usual sight. Uncertainty, of course, is daunting and dangerous. But I wonder, what new kind of sight might we acquire when things no longer look the same as they once did? How can a speculative imagination reshape our relationship to transforming the world around us? What new prophecies might emerge, if we practice speculation as a kind of divination?

The experience of crisis itself is not new. That’s something we can know with some certainty. We’ve been living in a state of crisis ever since Europe swept across the oceans, enveloping the world into the fold of colonial capitalism. That was a time in which Empire first embarked on the project of assimilation, turning many worlds into one. The start of the ‘modern’ world, of Empire’s world, marks the first global crisis – one we have yet to resolve.

Today’s pandemic is by all means of critical proportions. In all its calamity is it complex: it has many faces. But it does not come to us outside of history. Which is to say, it does not come to us outside of the crisis we have been facing for over 200 years. As anti-capitalist scholar and activist Naomi Klein points out, “When people ask ‘when will things get back to normal?’ We have to remember that ‘normal’ was a crisis. Normal is deadly”.

What would it look like to reclaim our agency in crisis?

Klein, an expert in understanding how capitalism weaponises disasters to reify itself, urges us to understand that there is a consistent pattern between crisis and capitalism. She likens the process to electro-shock therapy: by seizing advantage of the collective shock experienced by a population during disasters, ‘shock doctors’ (another word for capitalists who exploit disaster) rapidly set to work introducing new neoliberal measures that ensure both power and profit for private, corporate entities.

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, for example, private companies and military contractors turned up in the midst of the devastation, ready to find ways to profit by privatising housing and schools. The public commons were reclaimed entirely by the private, irreversibly shifting economic and social relations.

It’s like every disaster presents us with a fork in the road. The etymology of the word ‘crisis’ lends itself to this metaphor. ‘Crisis’ comes from the Ancient Greek word krinô, literally meaning to decide. Janet Roitman, in her research on crisis as an object of knowledge (meaning the way constructing something as a ‘crisis’ produces a particular narrative), traces the lineage of the common use of ‘crisis’ to the Hippocratic school. The connection between contagion and crisis, from the 4th century BC to today, feels significant: “as part of medical grammar, crisis denoted the turning point of a disease, or a critical phase in which life or death was at stake and called for an irrevocable decision”.

And yet, for the majority of us, our personal distance from real economic and political power makes us feel like we’re deprived of the agency of making a particular choice. It feels like history has made that choice for us, taking us through an endless loop-cycle of bad decisions. Colonial capitalism will always choose itself. There is only one decision that is to be made again and again: private property and profits over people.

But what if we no longer put our faith in the system to decide for us? What would it look like to reclaim our agency in crisis?

To be faced with a crisis is also to face that crisis head on. Or maybe we have more agency than we think. In spite of our seemingly personal distance from economic and political power, there are other powers that sit within our reach. As Roitman notes, crisis unveils latencies about the world, meaning that the way things work just below the surface becomes, for a moment, exposed. Today, those latencies are thrown up in the air for us to see on full display. We can see clearly the intersections of capitalism, colonialism, white supremacy and fascism, and it seems they have never been more hyper-visible (despite having always been visible for the global working class). As African-American Studies scholar Ruha Benjamin says, “we are seeing in every area of social life where racial inequality has existed, the coronavirus is shining a light on those inequities”, noting for example how the relationship between racial inequality and access to healthcare leads to a greater vulnerability for black communities in the States. Fatal inequalities, already lacing the experiences of indigeneity, gender, race, class and ability, are amplified. But simultaneously, we might also glimpse the source of our power.

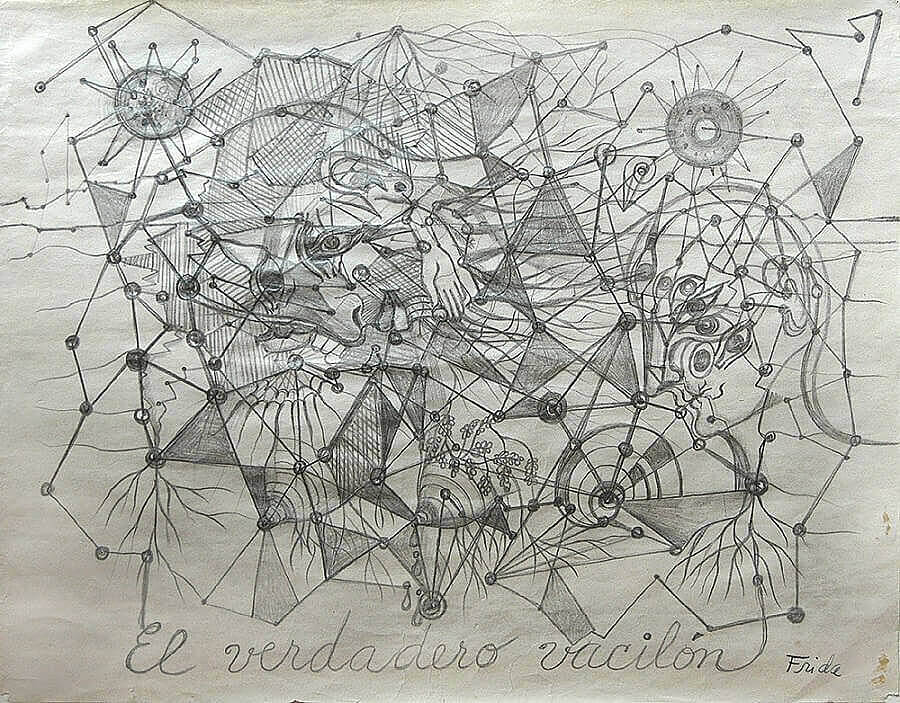

Enter the cyborg, feminist theorist Donna Haraway’s blashphemous, playful, cyberpunk revolutionary hero. For Haraway, the image of the cyborg represents both our agency and subordination to colonial capitalism, or what she calls “the integrated circuit”.

The cyborg, Haraway writes, “is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction”. We are cyborgs because we embody these fractured identities, and all the contradictions that entails. Part organic but, equally importantly, part machine and “integrated circuit”.

Far from ‘human’, the cyborg symbolises our social and bodily reality by emphasising our composite nature. We’re composites of all the technologies we have at our fingertips; extensions of them, as much as they are extensions of us. Capitalism functions like a circuit, relying on the smooth flow of production, labour and social reproduction. Each of us marks a dot connecting this global circuit, like the intricate joints of a monstrous machinery.

The cyborg is the bastard child of colonial capitalism

Haraway’s cyborg challenges our common perceptions of subjectivity and self. Western frameworks of the human, the self and the body tend to rely on the individual, reproducing binary distinctions between the private/public, market/home, personal/political and self/other. That is, according to Western ways of knowing the world, we understand ourselves as seperate from others, and not in relation to them, as if there’s no overlap between these categories. Instead, the cyborg sits in the space between these distinctions, in turn pointing to “the permeability of boundaries in the personal body and the body politic”.

It’s the cyborg’s position between these boundaries – sitting within, and embodying, the contradictions and inconsistencies of colonial capitalism – that gives it a special kind of consciousness; cyborg consciousness is class consciousness, race consciousness and queer feminist consciousness all in one. Cyborgs, says Haraway, are the “illegitimate offspring” of the system. The thing about illegitimate offspring is that they’re often “exceedingly unfaithful to their origins. Their fathers are, afterall, inessential”.

The cyborg is the bastard child of colonial capitalism, owing both its birth and alienation to its patriarch. But it is without inheritance, without obligation to continue its patriarchal lineage; this independence gives it its agency. The cyborg comes to embody “potent fusions, and dangerous possibilities” when it realises this power. In reconstructing subjectivity through cyborg theory, Haraway gives us a new opportunity to extend our social and political imagination, and therefore our realm of material possibilities.

I cannot think of a time when our organic and cybernetic interconnectedness has been more apparent. A virus that spreads through physical proximity has made hyper-visible the entangled nature of our composites. The irony is that physical distance reveals our closeness. We can no longer avoid the ways in which we are dependent on each other: requiring vigilant physical isolation confronts our organic interconnectedness by reminding us of the wetness of our touch; that constant permeability between my body and yours. We realise more and more how much our sociality occurs through our cyber-intimacy; our phones and laptops like a fifth limb, simulating a different sensory experience of social relations, in that porous space between absence and presence.

Our patriarchy is revealed in all its staggering inadequacy and absurdity

And, of course, our integration into the global circuit is exposed irrevocably by its breakdown. Without capital being generated in its excess, the circuit falters, leaving bare the frayed relationship between survival and the mode of production. From the closing of borders affecting the movement of labour, commodities and capital, to the halting of inessential work (for the most part, at least) revealing the futile nature of work for capital’s sake, our lives are revealed to belong to capitalism more than they belong to our communities. Such realisations force us to (re)consider whether capitalism could ever truly meet our needs.

Our patriarchy is revealed in all its staggering inadequacy and absurdity, its organic, bodily excess. The precarious migrant workers, refugees and global poor are categories of people generated by capitalism’s structural inability to account for the lives of those it produces through specific, historical conditions. It leaves them without welfare, health, or homes, because it has no ethical imperative to protect its most vulnerable.

In Aotearoa, we see how disproportionately such circumstances affect those already marginalised by the crisis of colonial capitalism. Those without homes, without jobs, incarcerated, or otherwise compromised, fall to far greater risks than the rest, because of the social conditions that already put some lives in far greater proximity to death than others.

Thus, the cyborg is implicated in the biopolitical warfare of colonial capitalism, meaning the way in which the system declares war on some lives. The cyborg is sometimes at odds and sometimes complicit in the way the system administers life and death. But it is precisely this way in which we’re implicated that gives us an entry point into subverting this very system. Our politics can come from this way of being: if we’re so integral to the circuit, that means that we’re also its biggest weakness, potentially its biggest threat, like the ghosts in the machine.

What’s at stake is our assumptions of what it means to be a body in this world; a body separate from the body politic. The corporeal form of the cyborg reminds us that our bodies are a site of capitalist production and social reproduction, all working parts of a sick system that administers precarity and death.

Crisis has always been a question of life and death. The decision of which moments in history get defined as ‘crises’ relates to the way power dictates whose lives matter, and whose deaths we take for granted. That’s why it’s so important to emphasise that the crisis has been ongoing – it’s shaped different communities’ relationships to death for over 200 years.

Perhaps we need a new definition of health. The kind that really gives life, rather than withholds death at its will. A definition that understands health to live in the relational space between us, rather than solely in our individual, bodily form. I wonder what kind of political and economic system could mediate this kind of health, by honouring the relationship between giving health and giving housing, welfare, dignity and, above all, land back. Health that holds us accountable to the resolution of the crisis of colonial capitalism and, in doing so, to each other. Such health requires more than the terms of our physical distance. It requires a decision to break from not only the structures that administer death, precarity and vulnerability, but, further than that, it requires the decision to resist those tendrils that try to creep through the cracks opened up in this pandemic; those that try to reappropriate the relational and the social, to further entrench the capitalist values of individualism and isolation.

Indifference, and the lack of imagination it brings, is no longer a tenable position

To return to the image of the cyborg, I wonder what other invocations and incantations we can appeal to, to help us reclaim our agency, reimagining our relationships to bodies, our technologies, and our entanglements with the social and political. How we might organise around new understandings of such entanglements, meaningfully recognising the complexity of cyborg interdependencies. Or organising, that is, in ways that respect and uplift the ways in which we are connected to each other and the systems we’re implicated in.

Indifference, and the lack of imagination it brings, is no longer a tenable position. We must begin to think of new ways of organising labour and resource, and recentring the values of a truly social, living world.

I think that crisis demands divination, because new speculative imaginaries can help to ignite the goals of our collective organising, compelling us towards new ways of being-in-the-world, together. Crisis has always been the time for rigorous, productive critique. This connection shares an etymological significance, as well as a politically urgent one. Such critique might propel us towards not only the decision we must make, but shaping the road that lies beyond it.