Redefining ‘refugee’: The resettled community and the art of be-coming

Georgina Langdon-Pole on an Auckland exhibition's delicate act of reclamation.

The state of being a refugee and the process of resettlement are interrogated in a new exhibition set up by an Auckland advocacy group. Georgina Langdon-Pole talks to the photographer and his subjects, and considers how the easy narratives of displacement can be complicated.

It is one of the most defining images of this decade. Three-year-old Alan Kurdi lying on a Greek beach: still, context-less, arms tucked in softly beside him. His body is straight, straddling the shoreline like the needle of a magnetic compass. Head guiding us toward the ocean, to Syria where he’d been forced to flee for his life. Feet directing us to the island of Kos, one stop on his family’s arduous journey to Canada, a destination they hoped would provide them with the chance to survive and live in peace.

The photograph was taken in 2015, a year when the amount of forcibly displaced people spiked to record highs. The UNHCR would go on to record that 65.6 million people, a staggering 1 in every 113, were displaced from their homes due to conflict and persecution. Yet statistics and numbers and words had repeatedly failed to expose the true plight of those who fled war and conflict in search of survival (and still do).

Who was Alan? What would he be saying and doing, had he survived?

His death left him voiceless. Yet his image has lived on, his body transformed into a contested space across the vast terrains of online media and global politics. It is one of a plethora of refugee representations that began to swamp Western newsfeeds and TV screens with the eruption of the Syrian civil war. Since his death, narratives about refugees have continued to circulate politics and the media in powerful, insidious and oftentimes misleading ways.

Aiming to shift dominant and damaging narratives about refugees, The Auckland Resettled Community Coalition (ARCC) is an organisation comprised predominantly of former refugees or members of the resettled community. The ARCC slogan: “nothing about us, without us” urges New Zealand organisations and institutions to place former refugee voices at the centre of resettlement practice.

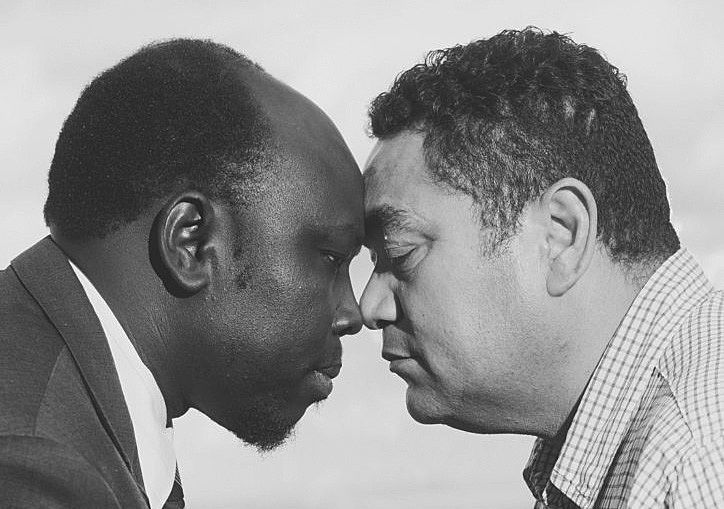

In coalition with photographer Nando Azevedo, the ARCC have developed an initiative titled: “New Zealanders Now - From Refugees to Kiwis.” The project explores issues of representation and identity, and is comprised of black and white photographic portraits of former refugees from 18 different ethnicities. The images have been displayed in a photographic exhibition (now showing at the Auckland Maritime Museum) and in a book.

Tasmine played a dual role, both developing the project and agreeing to sit to have her photograph taken. When I spoke to Tasmine, we sat cross-legged on the floor of her lounge, leaning in to hear one another. Pictures of earthy red hues lined the walls - reverberations of Rwanda, where she came from 17 years ago, at just 16 years of age. Tasmine explained the campaign evolved from the struggles the ARCC had engaging with young people, part of which, they realised, was strongly attributed to the stigma surrounding the term ‘refugee’.

(Tasmine) sees it as a form of resistance to being reduced to the label ‘refugee’, which has in the Western media, become synonymous with being a person of colour, being poor, and of being cast as ‘the other’.

For some members of the resettled community, resistance to the term ‘refugee’ is rooted in the challenge of transitioning from one culture to another. “You get teenagers who don’t know who they are anymore, if they are New Zealanders or if they are African, or Middle Eastern or whatever…because they are so stuck in balancing both cultures. It’s clashing and they don’t know where they should fit”, Tasmine told me. Having come to New Zealand as a young person herself, she identified with the challenges in navigating the space between two cultures: “You just feel like even if you come here as a young baby, or even if you’re born here, because of your colour you’re still called a refugee, you’re still being called ‘the other’.”

For Tasmine, having her portrait taken was a way to promote herself as a human being. She sees it as a form of resistance to being reduced to the label ‘refugee’, which has in the Western media, become synonymous with being a person of colour, being poor, and of being cast as ‘the other’.

The process of resettlement is fraught with challenges even without the stigma. Many former refugees experience a state of anomie, a term the sociologist Emile Durkheim used to describe the condition of internal instability occurring when a person’s common values are no longer understood or accepted, while new values and meanings have not yet developed.

In order to create new values and meanings, refugees look to society to understand how they ‘fit’. But they do so in a kind of cultural vacuum, having been stripped of the kaupapa that informs their way-of-being in the world.

It is within this state of oscillation that representations of what it means to be a ‘refugee’ become so powerful. Negative encounters with the label are not only subjective. How a resettled person defines themselves is deeply embedded in the regimes of ‘refugee’ representation; the myriad ways their experiences are framed, contained and narrated.

The term refugee is defined by the UNHCR as: “someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence.” Despite this, there continues to be an interchangability in popular understanding between the term ‘migrant’ (someone who actively chooses to leave their home country) and ‘refugee’ (someone who is forced to leave their home in order to survive). Golriz Ghahraman, a participant in the portraits and the first refugee to enter parliament in Aotearoa New Zealand, echoed this: “most people’s idea of what a refugee is essentially an economic migrant. They think refugees are poor migrants who lack personal resources.”

This misuse of the terms ‘migrant’ and ‘refugee’ occurs often in the media, often in the form of a failure to clarify. But the issue of refugee representation is also political. Terms like ‘queue jumpers’ are frequently used by the Australian government (and at one point, John Key) to perpetuate fear around the threat of refugees. The term ‘refugee crisis’ is itself reductive and distorted. It presents refugees themselves as the threat; as the crisis itself and not a consequence of it. All the while, the complex conflicts from which they have fled are ignored.

Simultaneously to this narrative, which implies some form of cunning and deceit, narratives of vulnerability project refugees as being helpless and unable to support themselves, perpetuating the view that refugees are a drain on New Zealand resources.

In this environment, New Zealanders Now – From Refugees to Kiwis is an attempt to resist and challenge the ideological lenses through which many people see new arrivals through the visual reformulation of identity. For many participants, there is not just one form of resistance. Abann (General Manager of the ARCC, and a participant and driver of the project), spoke to me of resistance as using the word ‘refugee’ for what it actually means, rather than trying to get away from it.

"For me it depends on the context, really. Because when you think of the word ‘refugee’ you also think about someone that has overcome, is resilient, you know, those words. For some of us the word refugee carries a sense of pride and identity.”

“There is a big misunderstanding with the New Zealand public around understanding what a refugee is; confusion over who is seeking asylum and those who’ve made NZ their home.” His view is that the label ‘refugee’ should be temporary, used to describe a person’s journey to escape conflict and persecution. Once refugees have been granted permanent residency or citizenship they are by technical definition New Zealand residents/citizens and no longer refugees.

Yet the label stays with them long after they have resettled, Abann explained to me: “We have three areas of the time factor: the past, the present and the future. We acknowledge our past - that we have a refugee background. But why do we have to be reminded? For us, dignity matters. It matters!”

The focus here is not about completely eliminating the word refugee, or forgetting the past. For many, the term refugee is also a positive one, and one they still use. Rosemine (Tasmine’s sister) joined our discussion and shared her experience of the label: “for me it depends on the context, really. Because when you think of the word ‘refugee’ you also think about someone that has overcome, is resilient, you know, those words. For some of us the word refugee carries a sense of pride and identity.”

What Rosemine, Abann and Tasmine share is ownership of the word ‘refugee’. All ground the word in their own context, using it consciously. The process by which former refugees define themselves and the very fact that meanings shift and change is a reflection of the complexity and diversity of the community. Here, the process of redefining is in itself a source of resistance to being framed as a homogenous group. An uncovering of the diverse array of cultures, experiences and journeys, which make the resettled community what it is.

The different ways people choose to define themselves, even in the wake of outwardly similar life events, demonstrate the transformative nature of identity. The late cultural theorist Stuart Hall stressed that identities are not fixed, but in a continual state of transformation. Rather than simply ‘being’, human beings are in a perpetual state of ‘be-coming’. Our identities are thrust forward through the passage of time, constantly intercepted by history, culture and power.

The portraits are framed affirmations of this on-going journey of be-coming. In her portrait, Tasmine chose to stand in front of the ocean. Like identity itself, the water is in a constant state of movement, ebbing and flowing against different shorelines. For Tasmine, the ocean expresses commonality and difference. It is a connector to Rwanda. More prosaically but importantly, she – like so many New Zealanders – values the beach as a place to think and just ‘be’.

For many participants, the images express the inseparability of commonality and difference they live day-to-day. There are points of similarity; of ways of being, which constitute who we are as New Zealanders. Alongside this are significant points of difference: the ruptures, which propel refugees to New Zealand and destinations all over the world. The junctures, which make diverse cultures unique. This enmeshment of commonality and difference in the lives of former refugees stretches beyond homogenous representations. In this way, the photographs are an example of the power of an image to express something words fail. As an act, the images translocate what has been fixed and veiled by representation, back into the realm of lived experience.

Reconstituting identity in a context where identities have been fractured is a delicate process. Like every artistic replication, the practice of representation is bound up in the politics of appropriation. When are images a form of resistance and when are they a form of appropriation? When do they empower and when do they objectify? These debates have long existed in documentary film and photography, but have taken on new meaning in an age when images, information and ideas churn through online spheres in complex and accelerated ways.

As a practice of representation itself, there was inevitably some scepticism about the goals of the project and how people would be depicted. Tasmine explained: “I remember at the beginning it was really hard to get people to even take pictures because they felt like ‘oh what is this going to achieve, is it the same thing that we just had to go through’. People felt like they were maybe being taken advantage of.” Nando, the photographer of the exhibition reflected on this: “That’s a fair concern. Every photography and film project has that – people are inevitably worried about having their image exploited.”

It is difficult to understand any form of representation without seeking to understand the positions of enunciation, the positions from which we speak, write or in this case, photograph. Nando doesn’t come from a refugee background. But he explains that the process of the project’s development was centred in the resettled community.

While other participants in the project experienced being pitched as ‘the other’, Golriz finds that media representation has often stripped her of her Iranian culture. Her success is often defined by her ability to assimilate into New Zealand and become ‘Westernised’.

“What gives this a bit more validity is the fact that it was made with the community. It was debated a lot and we had plenty of meetings on how we should go about it.” The participants in the project echoed this, sharing with me the diverse experiences of being represented and of re-presenting themselves through the project.

For Golriz, the process of coming to be involved in the project was an uncomfortable one to begin with. “It was actually a very fraught process for me in way. I had to think hard about whether it was going to be tokenistic.” It was the first time she had positioned herself as a refugee, fronting refugee issues. Underlying the process was a degree of unease at the idea of being presented as the ‘deserving refugee’, something people easily box her into because of her Oxford education and career as a human rights lawyer.

While other participants in the project experienced being pitched as ‘the other’, Golriz finds that media representation has often stripped her of her Iranian culture. Her success is often defined by her ability to assimilate into New Zealand and become ‘Westernised’. This is an attitude that Golriz resists. “Everything I have achieved is not just because I have assimilated. It’s because I am an Iranian woman.”. Having robust discussions about these issues, she found, was in itself a constructive experience - a way of confronting the way she has and continues to be represented.

For all participants, the lead-up to the portraits was just this, a series of on-going discussions where they played an active role in choosing how and why they would be depicted. It was – and still is – a process, stimulating awareness of the ways former refugees and New Zealand as a whole, are positioned by, and position themselves within narratives of the past, present and future. It is the mechanics of this process, as well as the diverse, complex – at times contrasting voices – that give meaning to the project as site of empowerment and resistance.

While the project’s slogan: #redefinerefugee, urges people to consider the ways refugees are misrepresented, an important component is about redefining New Zealand itself. The category of ‘the other’ is an expression of duality: the other, yes, but the self as well. Simone De Beauvoir stressed that self-awareness and the category of the other are inseparable, with the way we represent others an essential component of how we perceive and understand ourselves. As Ta-Nehisi Coates put it in 2015, in regards to the African diaspora: “I saw that we were, in our own segregated body politic, cosmopolitans. The black diaspora was not just our own world but, in so many ways, the Western world itself.”

How and why we categorise, represent and treat refugees reveals as much about New Zealand as the refugees themselves. Of who ‘we’ are and who ‘we’ want to become. It is, like the journeys of so many former refugees, not static, but open to change, to transformation. Alan’s image shows one of millions of intercepted journeys. Like so many, he was not given the chance to live. Though the image communicated vulnerability and seeming powerlessness, he is also an example of immense strength - the enduring and relentless human drive to be-come, in the face of such onerous odds. That’s the story (though the subjective experiences and consequences are heterogeneous) of all those who featured in the New Zealanders Now project. But it is also the story of New Zealand – of us . We all have to decide what we want to be-come.

New Zealanders Now: From Refugees to Kiwis is running at the NZ Maritime Museum until November. For more about the exhibition, prints and book go to: https://arcc.org.nz/newzealandersnow/