The Rebellious History of New Zealand Sign Language

Michelle Rahurahu Scott reflects on being a double-agent for the Deaf community and shares the story of her and her māmā’s lifelong conversation in Sign.

Michelle Rahurahu Scott reflects on being a double-agent for the Deaf community and shares the story of her and her māmā’s lifelong conversation in Sign.

The moment hearing people find out I’m fluent in New Zealand Sign Language, I get asked the same questions repeatedly. I’m thinking of getting a t-shirt made, actually, with frequently asked questions about Sign Language printed on it. I could direct them to the Deaf Aotearoa website’s FAQ section but it’s a lot more polite than the way I would put it.

The drafts I have for my shirt are a bit wordy. So far, I have:

- Wait, there’s New Zealand Sign Language? That’s dumb. Why isn’t there just a global Sign Language?

Sign Language is not only endemic to a country, it has regional variations too. It develops like every other language on Earth: slowly, over time, within communities. There is a New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL), an American one (ASL), a British one (BSL) and so on. No, we shouldn’t make a universal Sign Language just so that you could hypothetically use it anywhere.

- How do you explain like…astrophysics to a Deaf person? That’s too conceptual.

Hmm, have you been watching The Miracle Worker? Sign Language isn’t limited to the basic ‘bring-her-to-the-well’ moments; it’s a complicated language that has signs for every concept you can think of, every emotion, everything. The basic Sign you’ve picked up over time is basic because you’re basic…at Sign. Really, anything that you can express in a spoken language, you can express in Sign Language.

- Why don’t you understand the string of signs I looked up on the internet? I thought you were fluent.

Sign Language isn’t based on English. There aren’t corresponding signs for every English word or phrase. Sign has its own rules of sentence structure, grammar and flow. Each sign is just as specific as a spoken word and needs to be pronounced properly to be understood, with the right context. You haven’t learnt the flow of the language and the signs are clumsy in your hands, so you have a heavy, loud, hearing accent. No, I can’t understand you waving a few messy signs in my face. It’s hard to comprehend, I know, but Sign is its own full language, you absolute walnut.

If you’re feeling smug while reading this information, trust me, as a lifelong double-agent for the Deaf community, I promise you that you have asked, or would ask these questions in your doe-eyed naivety. Everyone asks the same awkward questions, there are no exceptions, and the Deaf community – Deaf, hard of hearing, CODA (child of Deaf adult), NZSL interpreters – we all smile and politely correct you, even when you rattle on about how you know the whole alphabet in Sign.

*

1878 marks the start of institutionalised Deaf education in Aotearoa. The missionaries realised there were Deaf people and worried that they weren’t receiving a Christian education, so they opened a school in Sumner, on the outskirts of Christchurch. The beginnings of Deaf education are a bit murky. It’s difficult to know where to draw the line, as there were two instances of education started by the same man, Reverend R R Bradley, who had nine children, eight of whom were Deaf. He employed an English woman named Dorcas Mitchell to act as a governess for his children using British Sign Language; she went on to teach several children in the South Island in British Sign Language. However, most records agree the very first school for the Deaf opened in 1878, on a plot of land Reverend Bradley offered to the government. After some trouble getting set up, the school opened with the unfortunate name Sumner Deaf and Dumb Institution.

Two years later, a congress in Milan consisting of educators who were all hearing decided that Deaf curricula should be oral, in order to assimilate Deaf into a hearing world. This had a snowball effect on the rest of the world; most importantly for New Zealand, it would strongly influence a Dutch educator named Gerrit van Asch, who would become principal of Sumner Deaf and Dumb Institution. Gerrit van Asch initiated an over-zealous ban on Sign Language in the school, even going so far as to forbid all pupils who could sign already from attending. Dorcas Mitchell applied for the job of principal but was denied the position.

In 1944, an additional school was opened – St Dominic’s School for the Deaf, in Kawakawa (Fielding). It’s the school that my māmā would attend, almost three decades later, starting from the age of two, and where the full ban on Sign Language was upheld legally until 1989.

Māmā doesn’t speak ill of the educators, or her time at St Dominic’s, and in my conversations with the Deaf community throughout my childhood, it seems like the experience is fondly remembered by all. Māmā still keeps in contact with a couple of the nuns who played the part of teacher, matron, and stand-in mother for the students of St Dominic’s; some she liked better than others.

Māmā (bottom row, third from the right) with her classmates at St Dominic’s. Most students are wearing the old hearing aids, which required a large battery pack to hang around their necks.

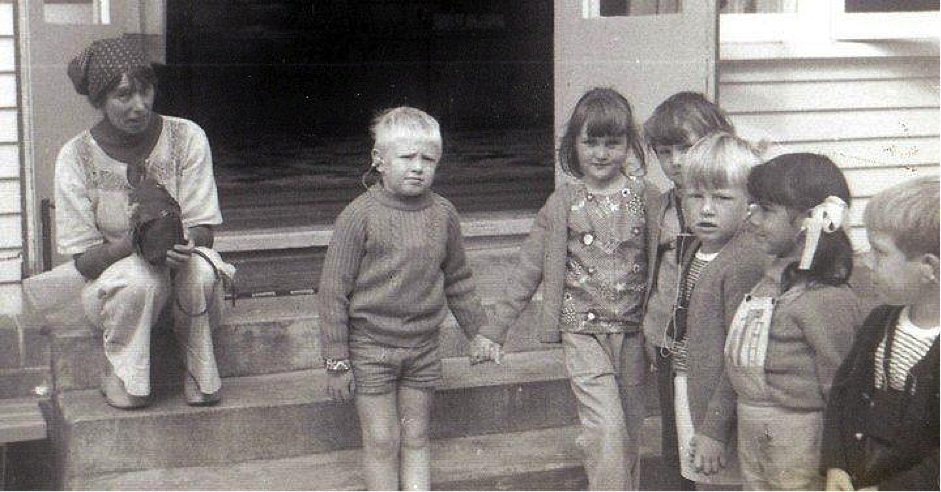

(Feature image, top of page) Māmā (second to the right) hand-in-hand with her classmates at St Dominic’s. On the far left sits a supervising nun.

Māmā seemed to be something of a prankster of St Dominic’s. One story she likes to tell is her time at a camp set up by the school. A group of children, including Māmā, tried to prank the nuns by streaming toilet paper through the trees and luring the nuns in with ‘ghost noises’.

I must remind the reader that this is a group of hard of hearing children, so they had never heard what a ghost is supposed to sound like. They only knew the shape that a mouth makes when imitating a ghost. When Māmā tells the story, I beg her to do the noise, which she does with gusto, and sounds something like “rooooooo”, which always makes me lose it. Māmā is a natural-born performer, we both are, so laughing only makes her howl louder until I can’t breathe. Imagine a group of children, under strings of toilet-paper trees, trying to scare the nuns with “RooooOOOooo” in the pitch black. The nuns were not taken off guard, and yet the children constantly tried to pull hijinks.

One night, the nuns blessed the children individually. When Māmā retells it, she assumes the role of the nun, eyebrows high and haughty, one finger wagging as she points at each imaginary child saying, “bless – bless – bless.” The children were sent to bed. The girls’ dormitory was on the top level, just down the hall from the nuns’ quarters, and the boys’ dormitory was below. The plan was to sneak down the stairwell and into the boys’ dorm. Again, these Deaf students had little to no concept of the sound they were making, so they clattered down the stairs, laughing and banging around. When they returned, the nuns were stood at the top of the stairs, arms crossed, informing the group that they’d lost their ice-block privileges. At this point in the story, Māmā would sign an action that looks like a dog lowering its ears, as the group of girls was sent back to their beds, which I’m sure needs no translation.

The students of St Dominic’s and the students at Sumner Deaf and Dumb Institution were taught to live their lives by compromise.

Recently, Māmā attended a reunion for the now-closed St Dominic’s, where they gave out a published history of the school. The history briefly touches on the ‘pioneers’ of St Dominic’s, a group of educators who travelled to Australia to study and learn Sign Language for the purpose of bringing their knowledge back to the school, only find upon their return to New Zealand that the laws had changed, confining their education to an ‘oralist tradition’ that prioritised teaching Deaf children to speak. The students of St Dominic’s were primarily taught how to ‘fit in’: how to talk like the hearing, to create the right sounds by mimicking the shape of a hearing person’s mouth when they speak, to write like the hearing. They were punished for using a language that was accessible to them. Despite the intentions of those pioneers, and the kindly nuns Māmā speaks so affectionately about, the reality is the students of St Dominic’s and the students at Sumner Deaf and Dumb Institution were taught to live their lives by compromise.

Fortunately, despite the heavily enforced oralist learning, Deaf children continued to use Sign Language in secret while attending school. What’s even more fortunate is that this secret rebellion was echoed throughout the country – groups of little rebels, signing in their dorms, under their desks, in the playground, keeping and designing a language that belonged only to them, despite the odds.

*

In the 1970s, a quiet revolution started in schooling. ‘Deaf Clubs’ in main centres around the country acted as social hives, steadily contributing to the widespread use of NZSL. In 1979, Sumner Deaf and Dumb Institution, adopted a ‘Total Communication’ policy, which allowed Sign to be used, and other institutions followed suit. But the style adopted was Australasian Sign Language, or TC (Total Communication), an artificial Sign Language, formulated without Deaf input that created equivalent signs for English terms, words and phrases, rather than the natural Sign taking place in Deaf social circles. The acceptance of Sign Language was a step in the right direction, but once again, it was on the hearing world’s terms.

By 1982, Māmā was thirteen years old, had completed her St Dominic’s education and by all reports, ‘spoke very well’. She was then bounced from several different mainstream schools, for different reasons; she was disruptive, she was difficult to teach or she failed to take in any of the curriculum. Finally, she was moved to Kelston School for the Deaf, currently facing a merger with Sumner Institute, which is now under the name Van Asch Education Centre. She spent a year at Kelston, studying and boarding, learning ‘life skills’ – mostly regarding flatting, cooking and a little bit of money management, but, most significantly, learning NZSL for the first time. I asked her if it was difficult to pick up, after using TC Sign. She says, “NO! – easy – quick – Sign Language – pick – up – straight away.”

When I ask Māmā about Australasian or ‘TC’ Sign, she usually rolls her eyes. I’ve had a few demonstrations of how it looked, with its unnecessary bridging words. Māmā signs it sarcastically, with a completely straight face, “I – am – Deaf,” which in my head sounds like a robot’s voice. We had a book of Australasian Sign Language that I intuitively hated because of its violently bright, highlighter-yellow cover, the title Dictionary of Australasian Signs emblazoned in green, and in fine print below: To communicate with the Deaf. I hated Australasian Sign, though I barely knew any. I could feel its strangeness in every movement; it creaked like a dusty, neglected chest. None of it made any sense to me. Māmā doesn’t like to dwell too much on the past, or “that – old – sign”.

*

I hated parent-teacher interviews as a kid. They were bane of my life, along with a whole stream of things that I groaned about, like interpreting the news, answering or making phone calls, and acting Deaf so we could both get discounted tickets. I tried hiding a parent-teacher notice from her once, but Māmā has superhuman senses. Apart from hearing, of course.

The moment she found the notice, I could see how hurt she was, I could feel her thinking, “Are you embarrassed of me? Why are you such a disappointing daughter?” What she said was, “Hide – from – me – why?” and we bickered. All in Sign Language, of course. If a hearing, non-signing person was there, all they’d get from the encounter would be two pairs of whirling of hands, and a furious string of muffled sounds.

The lecture ended with the exclamation of “Need – interpreter.” My most hated phrase. Interpreters meant a lot of admin had to be done, usually with my assistance. Luckily, there had been some developments at the time that cut my work down. Māmā had recently received a TTY, or a text telephone, that had a direct line to interpreting services. It was like large cell phone crossed with a fax machine. I didn’t think it was very cool at the time, in fact I purposely hid it out of sight if my friends were coming over. I couldn’t do anything about the doorbell that triggered flashing lights, or the loud Deaf woman standing in the kitchen, though.

I remember her angrily typing into the TTY, connecting to the service that relayed messages in real time to hearing people over the phone, trying to arrange an interpreter to come in the next day. She typed, then paused, her fingers waiting at the ready in mid-air as she read the reply on the screen. The news was bad, as I expected. She waved in my direction, exclaiming: “No – interpreter – too late! – You – need – translate – teacher.”

“I – hate – interpret,” I signed back. Māmā raised one finger at me, face in a pūkana, a domestic sign that she still uses on me that means “enough!” I stormed off to my bedroom, red in the face with teenage rage. I screamed into my pillow that I wanted to die, like a real brat.

At the interview, the teacher looked at the two of us like we were the coolest people he’d ever met, and said things like, “Oh, it’s so great that you’re bilingual!” So great. But I refused to smile back, resenting my teacher’s eagerness to see the zoo animals play. The other kids stared too. I slid down in my seat and tried to disappear. “She’s doing well in English,” my teacher said, too slowly, mouthing every word in the exaggerated way that hearing people do. “She’s doing really, reeeeeeally well.”

*

At university I started playing around with Sign Language and learned that hearing people lapped it up. I had enrolled in what I called a ‘blow-off’ class, a general education course that taught something along the lines of interpretive dance. I had to present a performance, but I’d forgotten about it and turned up to class unprepared, and sweaty from hurrying there. The rest of the class stood up one by one to present their various creations, while I squirmed in my cross-legged position on the floor. My name was called, and I dragged it out, really taking my time to get to my feet, then stood in the big empty space in front of the class. I stood there for a good half a minute, which I assume the audience received as a dramatic pause then just started signing a whole lot of nonsense. Like I expected, everybody loved it. I played it coy, saying I preferred not to translate what I had signed for ‘artistic reasons’. It was a complete cop out that earned me an A+ in interpretive dance, and a one-way ticket to hell.

This story reminds me of the debacle with Nelson Mandela’s Sign interpreter, who was exposed as a fraud: no one checks your credentials.

At home, I didn’t get the same adoration. I went back during the semester breaks, and every time I returned, Māmā would chastise my use of ‘old sign’, laughing haughtily and showing me the ‘new sign’ that was faster, or looked better, rightfully criticising how ‘tight’ I looked. “So – old-fashion,” she’d sign, making me feel like the middle-aged woman, and she the hip 18-year-old teaching me how to text.

In my absence, no matter how short, there were always new signs that had cropped up, replacing or sometimes adapting on old ones, collapsing into each other, streamlining. They were signs she’d picked up from her friends, the people I recognised from Deaf Association meetings, family events or barbecues, where we’d all sit in a circle and converse, cutting across the air between us with invisible threads. But at university I was out of practice, out of touch, completely unplugged from the mainframe of free-flowing, on-the-fly creation.

Each addition to Sign Language operates the same way memes or millennial lingo does. It’s linguistic development on speed.

Each addition to Sign Language operates the same way memes or millennial lingo does. Those with fluency in the language have the flexibility to understand a new addition to the language quickly through context and, if the individual likes it, they’ll use it. It’s linguistic development on speed, it does what it wants, and any attempt to capture it, in my mind, is a little maddening. I don’t envy the work the researchers who compiled the first Concise NZSL Dictionary, or the ones who maintain the wonderful online dictionary – they have their work cut out for them.

*

NZSL was adopted into the curriculum in 1994, the same NZSL that was used in the underground Deaf Clubs, fostered by Deaf and hard of hearing communities. Those wonderful rebels.

The same year, Māmā had her first child, a girl, and began to teach her basic baby sign: drink, food, sleep. This was where my education started, before I had the physical development for spoken language, in the arms of my māmā, starting a lifelong conversation that stretches over time, over dining tables, over cities.

I was given a great gift, a gift I didn’t appreciate for a long time. I took it for granted back in my schooling days, where everything was mortifying. But now, I can view it with pride.

I’ve always felt that NZSL is intuitive, with meaning existing in an amorphous shape above the sentence itself. Which means that some of the spoken grammar is done away with, like articles, conjunctions and prepositions such as ‘the’, ‘a’, ‘and’, ‘to’. The visual element relies on spatial connections rather than prescriptive grammatical ones, aligning meaning with the proximity to the body, or reference to a set-up image.

You don’t need a bridge between words when the speaker has set the table, put all their guests in their chairs, and put a calendar on the back wall for you.

Imagine the following sentence jumbled up in the air before you: “I had dinner with Marama and Peter the other night.” NZSL snatches the ‘I’, a sign that points at the speaker, then the image ‘dinner’, a sign that looks like putting an imaginary piece of food in your mouth, then it weaves in ‘Marama’ and ‘Peter’ by stating their names; first signing ‘Marama’ then directing the listener to a spot in the air that Marama is hypothetically sitting at (let’s say on the left of the speaker), and ‘Peter’ on the right. You wouldn’t add the words like ‘had’, ‘with’, ‘the’, ‘other’. These words are collapsed into the subject/object/verbs in context. So the result is: I + dinner + Marama (sitting on the speaker’s left for reference later) + Peter (sitting on the right for reference) + last + night. You don’t need a bridge between words when the speaker has set the table, put all their guests in their chairs, and put a calendar on the back wall for you. It’s a theatrical language that delights in painting pictures without cluttering each sentence with boring little words. I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to liken it to poetry.

*

Finally, in 2006, NZSL was made an official language of Aotearoa, alongside te reo Māori. I don’t know what it was like for the rest of New Zealand, but it was a full-on party at my place. The national Deaf Association put on events. The floodgates were opened for NZSL, and the next ten years welcomed significant resources for the Deaf, and for hearing who wanted to engage with NZSL. Tertiary courses were established in interpreting and relay services. But most importantly of all, NZSL was finally given the proper recognition it needs.

But there were, and still are, a few things left to improve. Nothing riles up the Deaf and hard of hearing community more than closed captioning (except cochlear implants, but that’s another story). Able, the closed captioning service for Aotearoa, tries its hardest to provide captioning for the Deaf and sound description for the blind, but it’s under funded by government, and the amount of content that is captioned falls woefully short of what the Deaf community have been wanting for years: mandatory captioning on all television broadcasts and on-demand services.

As for representation, that leaves much to be desired as well. I worked casually as an extra while studying and was offered a role on Shortland Street as a ‘Deaf Nurse’ for the annual NZSL Week. I had a simple directive: stand by Chris Warner as he signed “How are you?” and reply “Good” or something. I told Māmā immediately because she loves Shortland Street – every Deaf person does, because it’s the first show that got closed captioning and so was the first show the Deaf community could understand without exhausting lip-reading. When the episode screened, Māmā called me three times, as more of an alert than anything, posted on her Facebook, told all her friends, did everything short of hire a blimp with the words, MY DAUGHTER WAS ON SHORTLAND STREET.

However, when I saw her next, she was critical: “I – watch – yes – thought – that – all?”

*

For a time, my māmā and I lived in the same city as two adults and would regularly go on little outings. I took her to the museum a few times, which I knew she would enjoy since she loves taking photos of literally everything, photos of the two of us, photos of the ground, photos of the Sky Tower, “So – proud – baby – girl – grow – up – fast.” She took photos of the exhibits, taking photos of photos even. I wandered off to another exhibit, secretly because I was worried, she’d get me to ask the nearby people something cringeworthy, like to take a photo of us with the photo. As I admired a mannequin in a gown, a loud voice over the speaker system blared, “PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH THE EXHIBITS.” I knew it was Māmā the moment I heard it and rushed around the corner, just as another round of “PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH THE EXHIBITS” sounded, louder now. I found her standing behind the barrier, in the exhibit, perched on the podium, taking a too-close shot of a sculpture, even leaning on it a little. Good God. Two security guards had approached from the other side, one of them yelling at her. She didn’t turn. She looked like some kind of art anarchist. I held my hand out to them and explained that’s she’s Deaf, she didn’t know, she couldn’t hear the speakers or them. They told me I needed to get her out right away. I jumped the barrier and tapped Māmā on the arm. She jumped, turned to us finally, and her eyes bugged out when she saw the guards with their arms crossed. She gave me a little look, shrugged and said, “Oop.”

I’ve taken lately to sending videos to my mum, so that I can keep the signing muscle going, and explain things clearly to her, instead of messaging. Whenever I set up my camera to film, I can feel a fraction of the weight for a moment, a fraction of the energy required to come a few steps further out of my comfort zone. But after that moment of brief discomfort, I’m rewarded by Māmā’s smiling face, signing slowly, ending each sentence with a thumbs-up, like she would with a student.

The stories and opinions shared in this essay are my own, developed over a life in close contact with the Deaf community but I’m subject to fault, and constantly learning. My love for my first language will continue. The mistakes that were made in the past were built on Deaf exclusion. My number one resource for Deaf experiences will always be my māmā, and the people I grew up with that have trained professionally and work solely to benefit the lives of those in the Deaf and hard of hearing community. These benefits stem from the people that lived through the shifting tides of Sign Language in this country, and who love to share it with anyone who cares to learn. Deaf Aotearoa runs taster NZSL courses every year in combination with NZSL week for free (which are now filled up across the country), but the interest shouldn’t be limited to the one week. Seek out NZSL classes, engage with issues that concern the Deaf and hard of hearing community, pay attention to this community that is cultivating a rich language we can all enjoy.