Reality is Boring, Baby

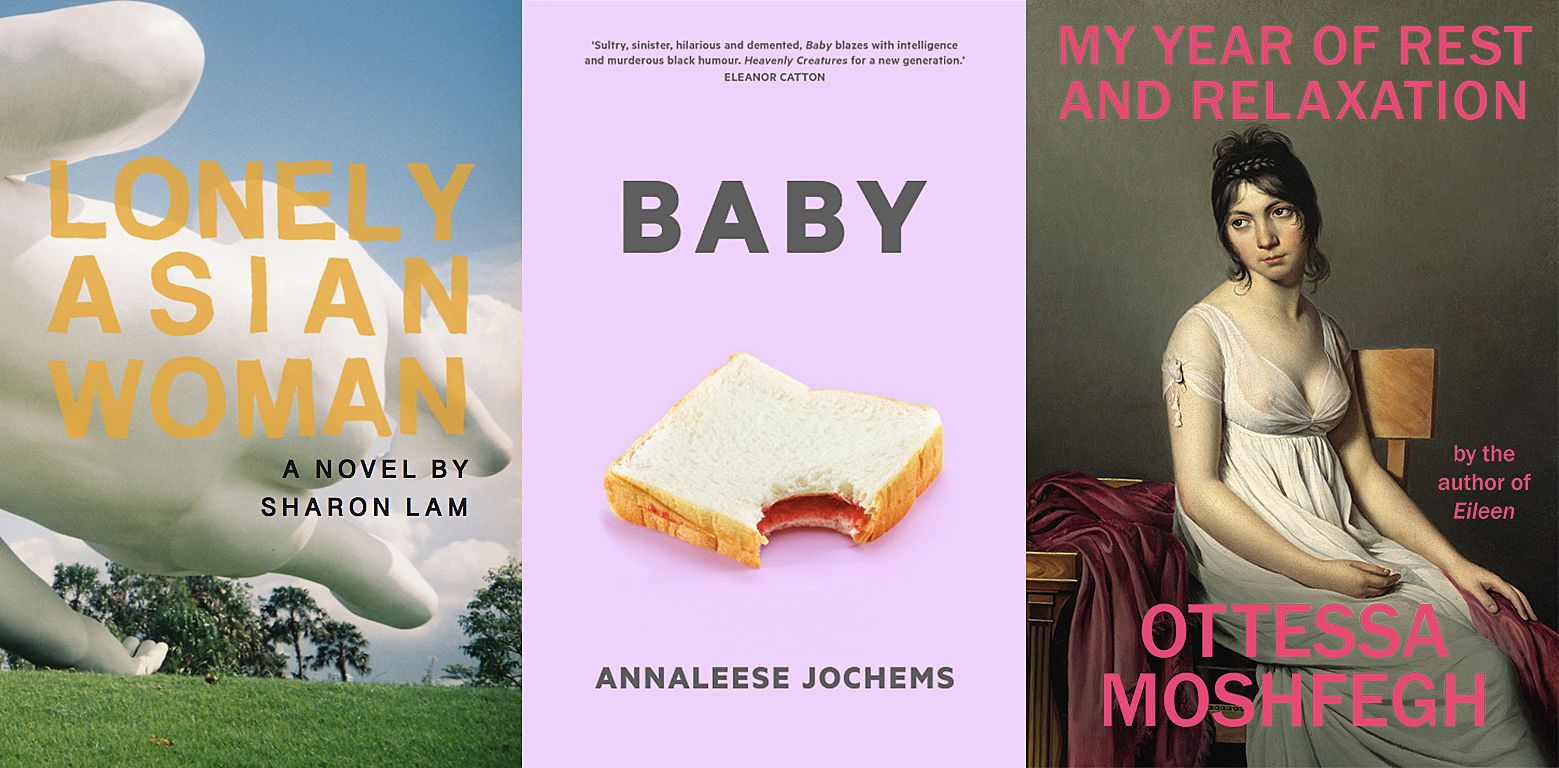

Three lonely millenial women seek love, meaning or at least… something to dull the malaise. But what’s real? And do we care? Mia Gaudin on Sharon Lam’s Lonely Asian Woman, Annaleese Jochems’ Baby and Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation.

Three lonely millenial women seek love, meaning or at least… something to dull the malaise. But what’s real? And do we care? Mia Gaudin on Sharon Lam’s Lonely Asian Woman, Annaleese Jochems’ Baby and Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation.

Sharon Lam’s Lonely Asian Woman (Lawrence and Gibson, 2019) and Annaleese Jochems’ Baby (VUP, 2017) are two of the latest debut novels from twenty-something graduates of Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters and they’re like nothing New Zealand literature has seen before. Now there’s Instagram and Tinder and Tom Hanks swimming at the pool. There’s a fake German tourist, a psychic Uber driver and a sake-selling blimp floating over Wellington. There’s a dog called Snot-head and a fish called Dog. There disbelief being suspended all over the place and no one is an influencer but everyone’s being influenced. “You don’t believe in reality,” the German tourist whispers to Baby’s protagonist, Cynthia. “You believe in reality TV.”

Baby’s Cynthia and Lonely Asian Woman’s Paula are also both twenty-something women, trying to figure out what they’re doing with their lives while looking at their phones. And while they may seem, at the outset, to sit alongside the frustrated depressives of Sally Rooney’s novels (Rooney has time and again been touted as the ‘the great millennial novelist’), there’s something stranger, more magical, happening in the worlds of Cynthia and Paula. The books are closer to the work of Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (Penguin Random House, 2018), a black-comic satire about a twenty-four-year-old woman living in New York in the year 2000 who drugs herself to sleep. So not a millennial, technically, but most definitely an inhabitant of a world that isn’t quite reality.

Lam’s Paula Mo is an unemployed architecture graduate living alone (save for her alter ego, Paulab, who can access her fridge and bank account) in an apartment bought for her by her parents in a city closely resembling Wellington. She has a core group of mates and a ‘crush’ who quickly disappears to Copenhagen, but she spends a lot of time skulking around at home (“time flew for people who took three hours to get out of bed”), worrying that she isn’t quite adult enough and that all of her friends have “something else” that she doesn’t. That is until, after being cooped up inside for four days during a storm, hungry and cabin-fevered, Paula ventures to the supermarket and, realising she has forgotten her wallet, steals a shopping trolley that contains… shock horror: a baby.

Unlike Paulab, the baby can be seen (and smelled) by people other than Paula. So it’s real… perhaps. It also shifts in form – losing a mouth one day, an arm the next – and is lighter than a cheesecake. Ha. That’s funny. Cool. It’s not really a shock. From the start of the book we realise that everything in Paula’s world is slightly off-kilter. It’s not even a question of suspending disbelief, as the book doesn’t ask us to seriously imagine an entirely new world, it just asks us to have fun and enjoy the ride as we encounter the figments of Paula’s imagination. She has to get comfortable with it too:

Paula didn’t know what the baby or the baby’s near nothing weight meant. But she was comfortable in her state of unknowing … She felt a change in her acceptance of reality, that her threshold for ‘normal’ had shifted – not upwards or downwards, it wasn’t a hierarchical thing – simply to a different position. She was somewhere else now. A place where the baby made sense. Not full sense, but enough sense to file it away in the non-fiction section of her brain.

The thing about Paula’s new plane of reality is that she finally has purpose. So while we’re still cruising around in the acid trip of Paula’s mind, taking a legless baby for a swim in a pool filled with Tom Hanks doppelgangers, Paula now has to deal with one of life’s most real (or is it surreal?) experiences – having a child.

The blurb on the back of the book explicitly states that “this is not the story of a young woman coming to her responsibilities in the world.” But there’s no doubt that the focus of Paula’s life changes, and, for this millennial reader who’s contemplating the possibility of her own terrifying motherhood, the baby provides a narrative hook: I’m invested in seeing how the thought experiment of “directionless woman with child in boring city” resolves itself.

The novel is indeed pushed forward with the peppering of strange goings-on, but pages are also turned because of the freshness of form and language play Lam employs ... not just playfulness for the sake of being clever; they provide an insight into Paula’s character : clueless and desperately seeking some sense of meaning.

Earlier this year Pip Adam interviewed Lam on her podcast, Better Off Read. Lam talked about building the plot up without knowing where it was going, and using surrealist elements as a way of keeping the reader interested enough to turn the page. The novel is indeed pushed forward with the peppering of strange goings-on, but pages are also turned because of the freshness of form and language play Lam employs. There are emails, comparative tables, pick-your-own-adventures, and elusive summaries of Tom Hanks films that are episodically inserted into the story. All fun elements, but not just playfulness for the sake of being clever; they provide an insight into Paula’s character: clueless and desperately seeking some sense of meaning.

When I first met Paula Mo in 2017, Lonely Asian Woman was a work in progress, a draft that developed during the year while Lam and I were in the same creative writing masters programme. So I’ve seen the book before in fragments – or should I say limbs – and to hold the final version in my hand is like holding a freshly formed baby, warm and giggling at the absurdity of the world Lam has created.

Lonely Asian Woman could easily have been called Baby. In fact, during our masters year, we bemoaned the fact the title had already been taken by Jochems, whose book came out as we were in the throes of writing our own. When I first read Baby it felt like a slap in the face, my mouth dropping as I gasped, not quite believing what I was reading. Not quite able to suspend my disbelief.

Cynthia is sticky, self absorbed, also unemployed, and obsessively in love ... How strangely vacant the characters are, as though their conversations never quite make sense, as though they talk past each other, words glancing off each other’s wet and empty heads.

Cynthia is sticky, self absorbed, also unemployed, and obsessively in love with her fitness instructor Anahera. She lives at home with her dad, and when Anahera shows up at Cynthia’s house, somewhat inexplicably, she drains her father’s bank account and they run off to Paihia together and buy Baby, a boat. I remember how impressed I was with the ghastly mood the book created, but also how strangely vacant the characters were, feeling as though their conversations never quite made sense, as though they were talking past each other, words glancing off each other’s wet and empty heads. “Maybe Anahera’s not even real,” our tutor said, a proposition that seems almost too easy – akin to ending a novel with “she woke up and it was all a dream”.

There’s no doubt, though, that Cynthia is an unreliable narrator. We see the world through her eyes only, and don’t get the opportunity to actually understand what’s going on with anyone else, particularly Anahera. So in that respect, Anahera never really does become real. Though, of course, Cynthia thinks she “can understand how Anahera feels just by looking at her body” and holds her up as a kind of god-like figure: “Things have been happening since before she was born, she understands, in places she’s never been, and Anahera seems to know everything … Cynthia wants only to be obedient.”

In a talk with Pip Adam during 2017’s Lit Crawl, Jochems spoke about the writing process as following an impulse from the beginning and seeing where it would lead. This is evident in the way the plot propels forward, the book being made up of 63 numbered sections, some shorter than a page, which build tension as the world becomes increasingly claustrophobic, leading to stranger and more dangerous events.

After the first night aboard Baby, “Cynthia wakes early, excited, and it’s like she’s slipped into reality, but not out of her dream” and from there, reality keeps on slipping. As the cabin of the boat and the monotony of the days (canned peas and corn, watching porn on her phone) start to close in, reality starts to bend and Cynthia becomes more and more delusional, unreliable. The sea rocks the boat, just as the storm lashes Paula’s apartment, both novels cleverly deploying repetitious time and confined spaces to jump their characters through the looking glass. Moshfegh, we’ll see, is also an expert at this.

Cynthia is obsessed with winning Anahera’s love, as though her reality has in fact turned into a reality TV show: “It doesn’t matter about the truth of anyone’s love,” Cynthia opines, after watching The Bachelor for three hours one day, “you either have the gumption and talent to win a place for what you’ll call your love, or you don’t and it means nothing.” Love, it becomes evident, is Cynthia’s main motivator and main cause of insanity.

Moshfegh’s unnamed protagonist in My Year of Rest and Relaxation also lives in an apartment owned by her parents (rich, dead) and quickly becomes unemployed, losing her job as a fancy Chelsea gallery girl after falling asleep in a cupboard, taking a shit on the gallery floor on her way out. Totally feral. Totally other plane of reality. She procures herself an irresponsible psychotherapist (“I’d discovered a pharmaceutical shaman, a magus, a sorcerer, a sage. Sometimes I wondered if Dr. Tuttle were even real”) who supplies her with a cascade of drugs to assist her on her mythical quest of falling asleep for a year and emerging as a better person.

Nothing seemed really real. Sleeping, waking it all collided into one gray, monotonous plane ride through the clouds. I didn’t talk to myself in my head. There wasn’t much to say. This was how I knew the sleep was having an effect: I was growing less and less attached to life. If I kept going, I thought, I’d disappear completely, then reappear in some new form. This was my hope. This was the dream.

I first read My Year of Rest and Relaxation on my phone. I was staying on the floor of my friend’s apartment at Columbia University and was in month nine of my own year of rest and relaxation. I was meant to be writing and had people to interview, travel plans though the States and Mexico, but it was just so easy to stay in bed. Sleep, I found, became my number one route for escaping the insurmountable task of writing a book.

“OH, SLEEP,” writes Moshfegh, caps shouting her poetic ode. “NOTHING else could ever bring me such pleasure, such freedom, the power to feel and move and think and imagine, safe from the miseries of my waking consciousness.”

All three novels play in some kind of dreamscape, but that doesn’t mean we’re going to wake up at the end of them and breathe a sigh of relief. They’re just reflecting the world we already exist in, where absurdities and images of things we’ve never seen ‘irl’ come at us thick and fast through our screens.

Lying on the deflating air mattress, Columbia students drinking matcha soy lattes in the street below, I was hooked. Finally, a writer who seemed to be doing something productive with sleep. I didn’t feel that Moshfegh was inviting me into an unimaginable world, I didn’t – save for the fact the protagonist ingested copious quantities of drugs without dying – have to suspend my disbelief at all. It was emotionally true to me that someone with dead parents and a dead-end job would want to put themselves to sleep for a year. I wanted to put myself to sleep for a year.

All three novels play in some kind of dreamscape, but that doesn’t mean we’re going to wake up at the end of them and breathe a sigh of relief. They’re just reflecting the world we already exist in, where absurdities and images of things we’ve never seen ‘irl’ come at us thick and fast through our screens. Paula sends a video of Shiba Inu puppies hugging each other to her friend Odie – “this u n me” she writes. Then she sends the exact same message to her crush. Nothing is real. Or it’s all real. We don’t need to suspend our disbelief in these books because we already exist in a world where anything is real, somewhere, on the internet.

Back on the air mattress (my reality) reading My Year of Rest and Relaxation, I rolled over and my sleep-related anxieties started to abate. I selected the passage in the Kindle app on my phone and sent a screen grab to a friend. “I only highlight my books in millennial pink now,” I wrote. “Fuck I love this writing.” I loved the writing because, I guess, it was fun. Reading Moshfegh’s novel is like sitting next to a hilarious drunk person at a dinner party who’s bitching about everyone and everything: her vapid art job, her try-hard friend, the new-millenium New York City. It rollicked along and I kept highlighting: an artist who freezes Siberian husky puppies in an industrial freezer, a dream of giving the doorman a blow job, a college entrance essay about a fake artwork called Stock Market Hamburger Lunch, parents whose sex talk consists of a warning about oxytocin (“for when you’re thrown out with yesterday’s trash,” her mother says). “Trevor,” the protagonist says of her dude-bro-banker sometimes-lover, “probably masturbated to Britney Spears.” Lols a minute.

Jochems’ rendering of Cynthia is equally dirty-sexy in that oversharing way, and adopts a dark sassiness similar to Moshfegh’s.

Jochems’ rendering of Cynthia is equally dirty-sexy in that oversharing way, and adopts a dark sassiness similar to Moshfegh’s. “Cynthia has a lot of options in regards boys but none are able to comprehend depth,” we learn of her sexual potential. (Note that Cynthia talks about boys, not men, revealing her bubblegum lack of maturity). A guy she fucked “sent her a picture of a Labrador, but that’s just more of the problem – that’s the only way boys of his sort ever like to have sex.” He’d probably like Britney Spears too.

Paula, on the other hand, is quirky and delightful rather than morbid and scathing. When an annoying friend of a friend shows up in the book (“She was the sort to proclaim that she had gasp been watching reality television … the sort to pair a secondhand sweater with three-hundred-dollar shoes”... she sounds a little like Cynthia!), Paula throws shade but she’s never as mean as the others. “Willow,” she says, “was pretty but unnecessary in most contexts, like the accents in ‘papier mâché’.” A tad bitchy, but mostly just cute.

So all the books are fun, bouncy, comical. But when people talk about whether a book resonates for them, it’s often asked whether characters are likable, and then whether they’re relatable. As though we can only relate to people we like. I certainly don’t like all these characters. Probably wouldn’t invite them to my birthday party. Moshfegh’s unnamed character wouldn't want to come anyway; she doesn’t really do friends. “I was both relieved and irritated when Reva showed up,” she says of her bestie. “The way you’d feel if someone interrupted you in the middle of suicide.” Lucky Reva. Cynthia, on the other hand, is desperate for attention but is such a self-obsessed maniac that a bloodbath would likely ensue before the cake was cut. Paula is just a bit of a moper.

But while I can’t say I like these women, that doesn’t mean I don’t relate to them. Unnamed is looking for change, Cynthia’s looking for love and Paula for purpose. Same! All of those things! All totally relatable. All real. I too am a millennial woman who has inappropriate love affairs, has been unemployed, addicted to sleeping, and to Instagram, has felt that my city is too small, has felt my body get flabby around me. My mother died, too! So why, then, when I finish the books, do I feel unaffected?

Do we really care if the characters get what they want in the end? And what makes us care? We’re let in when there’s an opening, a tear in the surface.

Perhaps it’s because relating is different to caring. Do we really care if the characters get what they want in the end? And what makes us care? We care about people we are close to. We get close to people when they let us in. We’re let in when there’s an opening, a tear in the surface, a vulnerability that lets us see deeper.

There’s a resistance from all three characters to show emotional depth. “I’m really going to miss eating with you,” Paula’s new squeeze Eric says to her before he leaves for Copenhagen. But Paula can’t respond, “she nodded and stared at the HEAVEN’S SAKE bottle, repeating the two words over in her mind in different voices.” Later, Eric tries to get through again, “Paula,” he says after they’ve had sex for the last time. ‘“Yes. That’s me,” she responds, then hides her head under the sheets. End scene.

There’s something frustrating about exchanges like this not progressing into heavier territory. I want to hear Paula and Eric actually have the awkward discussion about their feelings. “Is that deep, or fake deep?” I remember Lam often asking the class when we were critiquing each other’s writing. Deep, I’d say. Go deeper. But Lam holds back. And maybe that’s the point: Paula doesn’t know what she wants, so she avoids making connections. OK. I get that. Been there, done that, too.

It’s when Paula engages with her parents that there’s a more substantial tear in the fun, whimsical surface. She’s the child of migrants who have since moved back to Hong Kong to live.“Adulthood surely included crying for no real reason whatsoever after talking to your mother on the phone,” the narrator says after Paula has one of those frustrating ‘can you hear me?’ conversations, made even more difficult with her limited Cantonese (she doesn’t know how to translate “existential crisis” or “toilet plunger”). Melbourne writer Shu-Ling Chua praises Lonely Asian Womanfor its “I see you” moments, saying that Paula’s relationship with her parents, tinged with guilt and familial debt, will resonate for readers from migrant families. While I don’t quite cry alongside Paula, it’s in moments like these, fresh one-liners flirting on the border between cynicism and sentimentality, that I feel the most fondness and understanding towards her.

There’s less opportunity to empathise with Cynthia. Her character is developed in a similar way to the plot – Jochems seems to follow an impulse. The narrator (third person, but right up close in Cynthia’s head) layers up direct statements about Cynthia’s emotional inner world that help us learn more about who she is: “Cynthia’s always been what you’d consider a lonely person, but also, she’s someone with a limitless sense of meaning”; “Cynthia's struggling for hope and looking at a picture of her own pool on Instagram.” Noticeably, anything that starts to sound sincere is offset with humour or incongruity, meaning the writing veers away from being too earnest or touchy-feely. In a sense, Jochems’ technique for deflection is very similar to Lam’s; but the results are noticeably different. With Paula, there is a softening, a partial warmth; with Cyntha, we are always left feeling at a remove.

Though, again, it’s the revelations about a parental relationship that cast some light on Cynthia’s demented quest for love and attention. We learn that her dad bought Snot-head the dog after she cried for days on end as a teenager. “It was our best moment of love together. He didn’t hug me, but if he’d been that sort of guy I know he would have,” she tells Anahera. “I felt better then, when I knew he’d been listening.” That makes me care, a bit – though mostly for Snot-head.

Unnamed also has mummy and daddy issues. Compared to the other books, we get more of an insight into the relationship she has with her parents: it’s complicated, ghastly, traumatic, full of dismissals and lessons in how not to over-indulge. Unlike Lam and Jochems, this isn’t Moshfegh’s first novel – nor even her first about a pitiable yet slightly repellant young woman. Moshfegh knows the ropes.

Just like getting to know a new lover, the more we learn about unnamed’s childhood, cliché as it is, the more we start to care, to feel, even when she herself is numb. “I felt nothing,” she says, contemplating her dead parents. “I could think of feelings, emotions, but I couldn’t bring them up in me. I couldn’t even locate where my emotions came from. My brain? It made no sense.” That feels real. To me at least.