Real Talk: The Curatorial Practice of Ema Tavola

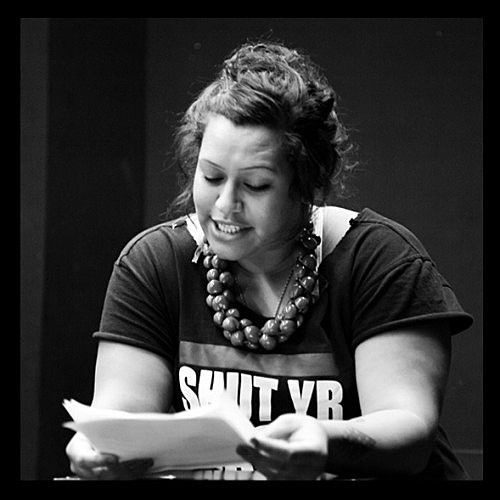

Daniel Satele profiles Auckland curator Ema Tavola, a woman who has helped shape the landscape of contemporary Pacific art in New Zealand.

You don’t meet someone like Ema Tavola very often: she perfectly balances energy, passion and intelligence and channels these into each project she works on – and she’s always working on a project. Ema is most well-known for having been the curator of Fresh Gallery Otara from 2006 to 2012, a platform she established and then used to put some of today’s major names in Pacific art on the map. When Auckland Art Gallery had its Home AKL survey exhibition of contemporary Pacific art last year over a third of the artists – and many of the artworks – had originally been seen in shows Ema curated, including Tanu Gago, Leilani Kake, Janet Lilo, Siliga David Setoga and Angela Tiatia.

What many people may not realise is that Ema didn’t just waltz into a pre-existing gallery and put some art on the walls. Under less-inspired leadership, Otara’s local, council-run art gallery wouldn’t have gained the kind of interest from the wider art scene that it now enjoys. For me, knowing Ema is a lesson in how much one person can make a difference in the world (and that says a lot because I’m a pretty cynical person).

Earlier this year Associate Professor Damon Salesa from the University of Auckland entered the term “segregation” into the public discourse about Auckland’s race relations, and this wider social dynamic is reflected in the art world. I doubt that “desegregation” per se is one of Ema’s priorities – in the sense that she is always very clear about her desire to attract and engage a Pacific audience, before any other – but her work is an important corrective to the status quo precisely for her privileging an audience others neglect. Refusing to ignore Pacific art, yet also avoiding the pitfall of fetishizing it for a mainstream, predominantly non-Pacific audience, has led Ema to do some of the most truly original curatorial work seen in Auckland during the last decade. The sad thing is that this kind of work falls to extraordinary people like Ema, demanding a level of effort and affect in excess of any job description, instead of being supported by the kind of systemic societal change that would make it ordinary.

Can you tell us a little about your childhood and adolescence?

I don’t remember much but I think I was often dressed in velour tracksuits. We had a deaf incontinent cat called Kennedy when I was about 7, and a King Charles Cavalier Spaniel called Rufus in my teens.

I grew up in Suva, London and Brussels. I didn’t really enjoy school. I used to draw on the back of the toilet stall doors and dream about getting tattoos.

The first CD I ever bought was “Regulate” by Warren G & Nate Dogg. That’s one of my favourite songs of all time.

I went to the British School of Brussels in Belgium for most of my school years and then did Seventh Form at Wellington High School. It was a pretty big shift; my life changed a lot when I was 16 – my family returned to Fiji and I came to New Zealand to finish school.

I grew up in a Fiji-centric household. There was no question about the pride of being a Fijian and a Pacific Islander. I grew up with a sense of service, loyalty and love for my country. I was also raised monolingual, so my love and respect for Fiji and being a Fijian is… in English.

Is curating an art form in itself?

For me curating is an extension of my art making practice. My curatorial practice draws on my experience and interests in installation and spatial design, social sculpture and interactivity. The politics of my art making are the politics of my curating, they are just different mediums that have the potential to affect different audiences.

As my art practice has evolved with me, my curatorial practice evolves with every project.

How did it feel the first time a show you curated opened? Does it feel different now that you’ve done it more, or does it still feel the same?

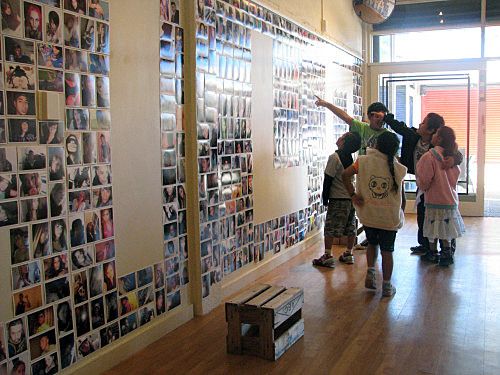

The first show I curated was called The artists are described as… Polynesian Male. It was a joint show featuring two painter friends. I remember the most important thing for me was representing them well. I remember people being blown away with how much attention I’d invested into little things, like cleaning the skirting board of the gallery and making sure all the light bulbs matched. The first show I curated was for Artnet Gallery in Otara… curating in South Auckland is the best feeling.

I’ve produced a lot of shows since then – over 70 shows in nine or so years. Managing Fresh Gallery Otara for six years gave me a lot of room to experiment, and I learned a lot about what works, what doesn’t – who to work with, who to avoid. With every project, every show, every mess, my position as a curator is galvanised a little more.

I still aim to represent the artist to the best of my ability. For me, as their curator I am their advocate, their hype man. Context and audience has always been fundamental to me; I strive to create opportunities for Pacific audiences to have access, and be empowered, to engage with art made by Pacific artists.

Who is the living artist or curator you would most like to meet in person (and haven’t done so yet) and why?

I’d love to meet Thelma Golden, the Director and Chief Curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York City. We both see the potential for art and exhibition making to change perceptions about our communities, since African Americans and Pacific Islanders in Aotearoa both experience marginalisation, systemic inequalities and misrepresentation.

I remember seeing Thelma on the “Power 100” list in ArtReview magazine in 2009; she ranked 78 on this list of the most influential people in the art world. Holding her own on that list, she got me excited about the potential of believing wholeheartedly in a curatorial agenda rooted in socio-political substance. I’d LOVE to meet Thelma, and hang out at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Is there any particular style or method of curating that you dislike, and if so, why?

There’s so much about the art world I dislike… there’s so much I feel no connection with, no emotional response to, and so much I refuse to waste my intellectual energy on accommodating. I don’t have time for indulgent, art school masturbation.

I love clever curating… which makes me think about space and my physical presence in relation to art. I like to experience an exhibition; when it makes me feel like I’m meant to be there, and that this artwork is for me to experience – not just casually hanging in a room that people may walk through. I like when the artwork’s audience is considered respectfully and genuinely.

What is the hardest thing about being a curator?

I’ve spent most of my career curating as the manager of a gallery, and for the past 12 months I’ve been working without one. The difficult thing about curating without a gallery is not having a gallery.

There’s a whole different social dynamic to meeting artists and talking about doing projects when there’s no gallery to slot right into. Suddenly funding and quite intensive administration and marketing are part of curating. Before, I had assistance and budgets to do this kind of thing.

Whether it’s about curating or not, the hardest thing about working from the heart is burn-out. Working with artists and artwork I love, and curating for a community and socio-political space I draw energy, sustenance and inspiration from, I’ve found it hard to stay within my physical limitations. As in, I work myself half to death – I’ve been in and out of hospital and endured tragic repercussions. I have to set boundaries and keep myself safe.

What’s been the highlight of your career as a curator?

I loved receiving the Creative New Zealand Arts Pasifika Award in 2012 for ‘Contemporary Artist’. Having my curatorial practice recognised as a contemporary art practice from the Pacific Arts Committee was pretty monumental. I thought of the late, great Cook Islands curator Jim Vivieaere that night… his legacy and position, and what a gift it was to have been around him, to learn from him. It was an award I felt represented all the hard-working people who stand behind the artists, working long hours to support other peoples’ visions.

What projects are you working on over the next 12 months?

I’m currently in the midst of a feverish fundraising effort to help get Leilani Kake and I to the Pacific Arts Association 11th International Symposium in Vancouver in August. We’re both delivering papers about contemporary Pacific art languages, South Auckland and grassroots curating. We’re also both full-time post-graduate students so we planned a series of fundraising initiatives which started with a really successful crowdfunding campaign. Now we’re selling hand-printed t-shirts and bags and on Thursday 25 July, we’re holding an art auction at Te Karanga Gallery on K Road.

I’m also curating the first exhibition for the Otara Light Boxes due to be launched in October during Otara Fest, part of the Southside Arts Festival. Part of that project is a photograph by Vinesh Kumaran from his on-going series documenting dairy owners. I love this body of work and am excited to see where it will go after this first showing.

In 2014, I’ll be working with Vinesh again to create the final chapter in our trilogy of portrait-series made at the annual Polyfest festival in Otara. In 2009, we collaborated on a series documenting personal style and fashion statements and last year we shot a series about hair styles. The concept for the 2014 series is yet to be decided, but it’ll be a goodie… It’s South Auckland social history represented in style and swagger, I love it.

I’ve been teaching a paper called Pacific Art Histories: An Eccentric View at Manukau Institute of Technology this year, and I’m really looking forward to delivering the paper again next year. Discussing Pacific art, history and ideas in Otara feels so right.

I’ve also been flirting with the idea of opening an art gallery in Ōtāhuhu. It would be a labour of love, but it’s something I think I have to do.

You can find Ema online by following @ColourMeFiji on Twitter and at pimpiknows.com