All The Knowledge We Need to Survive: A Review of ransack

Jackson Nieuwland reviews essa may ranapiri’s debut collection of poetry, ransack.

Jackson Nieuwland reviews essa may ranapiri’s debut collection of poetry.

ransack is a landmark in Aotearoa publishing. A collection by an openly takatāpui/nonbinary poet, writing explicitly about queer issues and experiences, published by Aotearoa’s largest publisher of poetry. I and many others have been waiting for this for a long time, longer than we ourselves have even realised, and essa may ranapiri has delivered it for us: a book that speaks to our experience, a book full of beauty and pain.

ranapiri is quickly building a reputation as one of Aotearoa’s most prolific poets. If you’ve picked up a local literary journal in the past couple of years, you’ve almost certainly held ranapiri’s words in your hands. And the holding is important. There is a physicality to their poems, they make use of the entire page, stretching from margin to margin, words creating walls, walls creating space, space holding meaning.

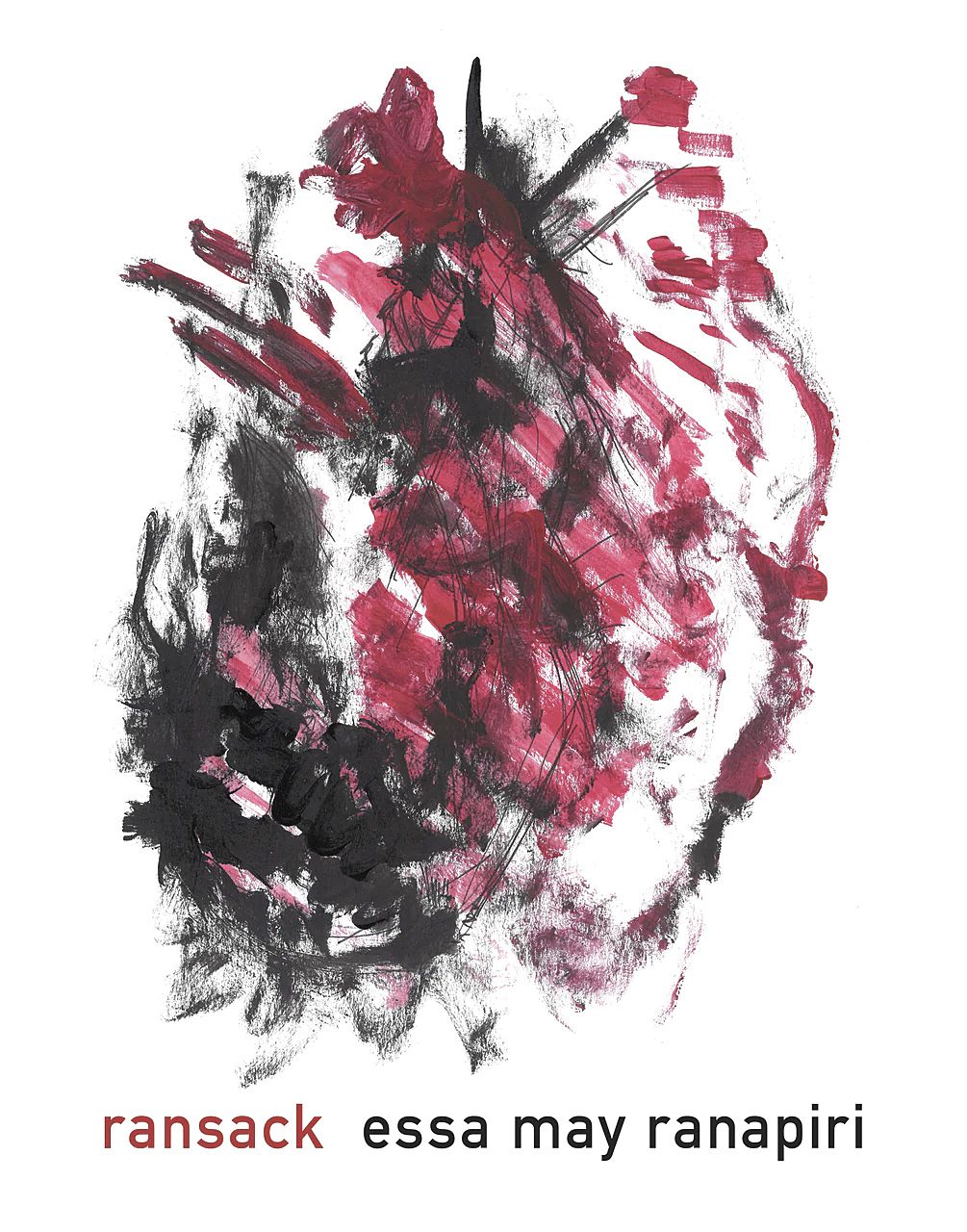

And now we have ranapiri’s debut collection in our hands. An object representative of what we’ve seen from this poet thus far and gesturing to where they might go in the future. From the cover image, painted by ranapiri themself, to the avalanche of colliding language and forms that make up the text, ranapiri cultivates chaos. They aren’t afraid to get messy, to explode language and let the shrapnel fall where it will.

Not mentioning the queer nature of this collection would not only be a disservice to ranapiri, it would also be a disservice to the work itself. Flicking through ransack you’ll find poem titles like ‘the nonbinary individual’, ‘Songs of an Enby’, ‘she cut her face shaving’, and ‘takatāpui’. Delving into the body of the poems you will read a treatise on nonbinary identity, a character with xe/xir pronouns, an exploration of the different forms of passing, and a series of letters addressed to Virginia Woolf’s Orlando – a character (based on a real lover of Woolf’s) who transformed from man to woman and lived for centuries, with a fluid cast of friends and lovers.

The poem ‘the nonbinary individual’ reads like a page torn straight out of a gender studies textbook. In fact, it gives the best explanation of nonbinary gender I have ever read. This technical passage systematically corrects nearly every misconception people have about nonbinary people, with lines like, “pronouns are not necessarily related to gender”, and “The nonbinary individual is biologically nonbinary.” The prose of the poem is framed by two stanzas of lyrical verse, which use a more heightened language to describe images from nature, suggesting that nonbinary gender is just as natural (if not more so) than male and female. Dear teachers, please teach this poem to your pupils. You have no idea how much it would help.

The letters to Orlando are interspersed throughout the collection. These prose poems form the heart of the book, offering a more intimate and interior view of the speaker. Reading these poems we feel as if ranapiri is writing directly to us. The language is restrained in a way that we don’t find in the rest of the collection, which gives it all the more power. ranapiri writes plainly about everyday activities and concrete events: a dog barking in the backyard, mould growing in the bedroom, their nan telling them how to get ready for a date. They make philosophical observations about society: “The way we constructed identity is all wrong. A person doing a thing becomes a thing thing associated exclusively with that doing. The person who farms is a farmer, the person who writes is a writer, the person who kills is a killer.” They also question Orlando, looking for advice on how to exist in this world and society as a genderqueer person.

These are the poems from the collection that touched me the most, the ones I will continue going back to for years to come, and the ones which I believe might show us where ranapiri’s writing might go in the future. This series feels something like a foreshadowing of ranapiri’s Echidna poems, which have begun finding their way out into the world. While the two sequences are stylistically different, both use existing characters from literature as a way for ranapiri to interrogate their own identity and the society surrounding them.

Even when the content of the poems isn’t explicitly queer, the language is inherently so: “a troupe of gasbags / instinct webs the company / to a canopy / of eyes.” Language has been weaponised against LGBTQIA+ people for so long that now the process of using language in non-sanctioned ways becomes a political act, a way of taking back power and agency. Radicalising language is a way of making the form of the text match its content, or as ranapiri puts it, “To provoke the confusion and alienation I often feel”. When they write “feed on the slash” in ‘Chemicals in Bodies’, they could just as easily be referring to the typographical slashes that are used to denote line breaks or pauses in a poem, or the liminal centre of a Venn diagram; a space that all queer people must inhabit. In a 2018 interview for 4th Floor, ranapiri spoke to me about what queering language means to them:

It means to undermine normative ideas about identity and challenge assumed structures of power. It means to decolonise the mind. It means that the language we have now needs to change to suit us as people and not the other way around. It means that we need to resist capitalism and other dehumanising systems that hurt us every day. It means to write without apology, without appeal to simple straightforward meaning, but to let the collapsing paradoxes of human perception just fucking have at it on the page.

The queerness of their language is what makes ranapiri’s poems so distinctive. They utilise a cacophany of different techniques in order to queer the language of ransack: lines break in the middle of words, paragraphs break in the middle of sentences, alignment switches partway through poems, sentences are broken up by scattered slashes and asterisks, academic prose quickly cuts to short lyric lines.

Am I really arguing that poetry is inherently queer? Maybe I am.

Of course, this smashing and collaging of language is the job of all poetry, not just queer poetry. Poets love nouns acting like verbs, and verbs masquerading as adjectives. What would be the point of a poetry that follows the rules of language exactly? Even the line break, the defining characteristic of poetry, is a shattering of grammatical rules and conventions. By breaking the conventions of prose, poets can create layers of meaning and rhythm that don’t exist in the same way in prose. By breaking the gender binary, genderqueer people reveal identities and experiences that aren’t represented in our patriarchal capitalist society. Am I really arguing that poetry is inherently queer? Maybe I am. After reading ransack could I really argue anything else?

ranapiri’s queering and radicalising of language is not solely a political statement, it is also a poetic one. ranapiri refers to it as “an exercise in play”. The unconventional use of language can lead to beautiful phrases and images that could not exist in any other context. Who is a grammarian to argue with the strange gorgeousness of lines like “it consumes it and is made by it planet and body” and “how your mother would make lucky space with the Bible embedded in the hyperlink of your name”?

I do want to make it clear, though, that the queer lens is not the only one through which ransack can be read. There are poems here about the Tainui waka travelling to Aotearoa, the effects of colonisation on Māori society and oral tradition, the story of Tūtānekai, Tiki and Hinemoana, and snatches of Pōkarekare Ana woven through the text.

In the acknowledgements, ranapiri mentions being inspired by a range of writers including John Milton, Hana Pera Aoake, Gregory Kan, Lyn Hejinian, Jos Charles, Catherine Chidgey, Tayi Tibble, Alice Te Punga Somerville and Karl Marx. These writers span a vast range of styles, subjects and contexts. With some of them the influence is clear, ranapiri borrows blatantly from them; with others the relationship is a mystery. No one aspect of the work stands alone, they support and inform each other, creating a complete whole. The strands of gender, Māoridom and language weave together to create a new kete o te wānanga, full of the knowledge we need to survive during this current period of history.

The kete that is ransack feels full to overflowing ... as if the book is made of many books, as if the book is a library all by itself.

The kete that is ransack feels full to overflowing, so when ranapiri told me that “it was originally around 350 A4 pages and featured a lot of characters from other stories and Greek mythology and had this strange modernist science-fiction setting”, I wasn’t surprised. Even though ranapiri cut more than two thirds of the manuscript prior to publication, the book still carries the weight of that text. It is almost as if the book is made of many books, as if the book is a library all by itself.

One of the most powerful poems in the collection is ‘Con-ception’. It follows a young mother and her baby from conception to premature childbirth. The narrative is told in brief vignettes, capturing day-to-day moments along the way: going for a run, vomiting, a sleepless night, painting a landscape. These sections are intercut with bracketed snatches, narrating what is happening inside the mother’s womb, often using highly specific scientific language: “it’s a blastocyst now”, “umbilical replacing yolk sack”, “buds of enamel calcium mix inside the gums”.

ranapiri is simultaneously engaging in language play, testing the limits of language, and creating meaning in that space between the physical body and scientific abstraction.

I asked ranapiri about their reason for using scientific language in their poems and they told me, “Firstly, I like the sounds, scientific words have interesting sounds and it’s weird they’re so disconnected from the body even when referring to the body… it’s this abstraction that has tried to define our own bodies away from us.” ranapiri is simultaneously engaging in language play, testing the limits of language, and creating meaning in that space between the physical body and scientific abstraction.

ransack is a book full of journeys: from conception to birth, a waka’s journey to Aotearoa, a letter’s journey to its (fictional) recipient, from closeted to openly queer. Some of the poems read like lessons – the closing poem, ‘takatāpui’, teaches the reader the traditional Māori approach to gender – but these lessons don’t come from a place of superiority. Reading, I got the sense that ranapiri was learning these lessons themself while writing the book and sharing them with us because they thought we might find them useful. The entire collection is suffused with a feeling of questioning, searching, reaching for something. The speaker questioning society and why it treats indigenous and LGBTQIA+ people the way it does, and the speaker questioning themself and their identity: “I want to be fully replaced.”

ransack is a book full of journeys... the entire collection is suffused with a feeling of questioning, searching, reaching for something.

This is a book for the marginalised. ranapiri makes that clear from the dedication, “for all of us whom the gender binary struggles to consume”, and they told me that their hope for the book is that “people who don’t usually see themselves in poetry find themselves here”. ranapiri never comprises on language, content, or themselves.

Not all poetry lovers will appreciate this collection. Some might find it too dense, experimental, chaotic, demanding. From my perspective it’s those exact qualities that make this work vital. The shrapnel of language pierces the reader with the accuracy and necessity ofa surgeon’s scalpel. ranapiri puts it best in ‘Sensephemera’, where they write, “I can feel the whole thing moving in tiny ways.” I, too, feel moved in so many tiny ways.

ransack is published by VUP (July 2019)