Raised Amongst the Kainga

Reminding us of the importance of educators and community, painter, printmaker and educator Dagmar Vaikalafi Dyck remembers the art kainga who raised her.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

“Whaea Dagmar, I want to be an artist just like you!”This is the child’s voice that I hear almost daily in my role as art teacher at Sylvia Park School in the heart of Mt Wellington. “But you already are one!” is my immediate reply. This echoes my fundamental belief, as Picasso said of himself, that each of us is born an artist but it's our navigation through our formative years via home, school and community that ultimately determines our future course as a creative. So how exactly have I managed to pursue a life in the arts? One thing for sure is it hasn’t always been easy but I wouldn’t change it for anything.

Rewinding the clock, I am a first-generation New Zealand-born child of the 1970s. My papa was born in Danzig-Langfuhr, Germany, today Gdansk, Poland. My opa was killed on the Eastern Front, which meant my oma and her four children became refugees following the war’s end in 1945. As a result, my father was thrust into work early and became a house painter, training in the Black Forest and Switzerland. Restless, at the age of 21, in 1957, he left his German homeland and took a ship bound for the other side of the world, to New Zealand, where he would meet my mother. My mother was born in ‘Utungake, in the northern island group of Vavaʻu, Tonga. Her ancestry also reaches from Europe, where my great-great-grandfather left Pyritz, Pomerania, part of the Prussian Empire, and joined a group of Germans that settled mainly in the Vavaʻu group. My great grandfather Vili was a boat builder and my great grandmother, Ofa ki Vavaʻu Tuʻanuku, listed her occupation on their marriage certificate as ‘tutu’, one who beats tapa. Art is in my blood.

My mother possesses the most skilful set of hands I know.

My mother was part of the Pacific mass migration to New Zealand of the 1950s and 60s. Sadly, I don’t recall my maternal grandparents as both died before I turned five. I am my grandmother’s namesake and I often wonder how different my life might have been had she been around to speak Tongan to me. My parents met on the dancefloor of the infamous Orange Ballroom, where my Uncle Bill Wolfgramm and his Islanders played all the hits. Both of my parents experienced a few years of rather interrupted schooling, yet their common sense, entrepreneurship and hard work ethic allowed us a secure upbringing. My father owned a painting and decorating business, complete with a fleet of VW Kombi vans. He’s always had an eye for colour and is a highly disciplined person. My mother possesses the most skilful set of hands I know. From sewing to cooking, baking to gardening, whatever she touches is quality.

Being an immigrant family, we held onto customs and traditions, both Tongan and German. I was the middle child, and my memories bounce between summer trips back to Vavaʻu and the ski slopes of Mt Ruapehu in the winter. Weirdly, the polarising opposites of my parents' cultures never felt out of place and I feel so much richer for them. In 1984, when I was 10, my family and I spent a year in Vavaʻu establishing our family business. During that year we lived in the old family homestead, Hikutamole, with the ocean literally five metres from our doorstep. This experience at such a young age greatly shaped my heart’s connection to Tonga. This wasn’t a strange land or a holiday destination. This was my family, my home, my roots. It’s hard to put into words because it’s such a full sensory experience, but every time I go back to Tonga, I feel an immense grounding. Over the next two decades, most summer holidays were spent back in Vavaʻu, providing me with a regular opportunity to stay connected to my village and family.

Raised on Auckland’s North Shore, I attended Westlake Girls High School during the mid to late 80s. I recall there were only a few other Pasifika students and certainly none identified as Tongan. To a large extent, I experienced positive interactions with teachers, particularly with my PE and art teachers. There was the assumption from teachers and students, however, that I was Māori, merely because of my skin colour. I do not remember having conversations with teachers about my exact identity, an experience that made me feel culturally invisible, except for in the art room. That was different, there I was encouraged to express my true self. My teachers would tell me, “Dagmar, let your art be your voice to show people who you are and where you come from.” I’ve never looked back.

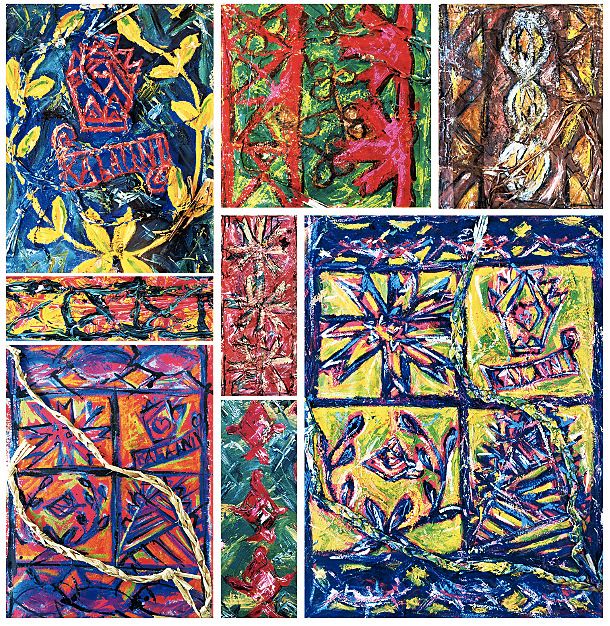

Dagmar Dyck in third year undergraduate show in 1993 at 22 years old. Woodcuts on feta’aki (Private Collection)

Dagmar Dyck's Bursary Painting examination artworks – 1989

I was meant to drop art as a subject after the mandatory third-form art classes. Like many, my well-meaning parents had a different view of what career would suit me best. On the advice of my father, I was instructed to take French, German, economics and accounting. Considering his vision for me to become a diplomat, these were wise choices. However, my art teacher at the time, Judy Darragh, recognised a creative capacity in me that I was not fully aware of. And she did something critical. She sought out the careers advisor, noting, “When Dagmar comes to choose her subjects make sure she takes art. I see her potential.” Consequently, economics was dropped and replaced by visual arts. That one deliberate act by Judy, backed by receptive parents and a supportive art department, set me on my pathway in the arts.

In 1995 I was the first woman of Tongan descent to graduate from Elam School of Fine Arts, at The University of Auckland. At the time it was neither mentioned nor celebrated. I was simply a fresh-faced undergraduate living the dream, creating her stories within the studio walls of the infamous ‘Mansions’. However, my journey into Elam had been fraught. Despite my teachers placing me first in my class in Bursarypainting, my actual assessed mark came back from the external examination as 64 percent. I felt vulnerable and my confidence took a knock. How could my marks be so drastically different when viewed by a complete stranger? The feeling of failure was acute, my dream to attend art school shattered. Thankfully, at the prerequisite university interview, my ability to share with lecturers Carole Shepheard and Don Binney that – beyond colourful patterns – my images spoke of my family, culture and identity satisfied their selection criteria.

While I loved being at Elam, I struggled for the first two or three years to find my voice. The sheltered environment of the secondary school art room didn’t prepare me for being surrounded by 39 other exceptional artists. The downfall of comparing myself to others thwarted my progress, with my confidence taking another knock. But I hung in there. Elam at the time still had separate, well-resourced departments with great technicians and its own onsite café. Given I had only done painting at school, I chose printmaking as I wanted to leave university with skills and techniques that required careful tuition. I was not disappointed. Woodcuts, lithography and screen-printing were my go-to print media. I have always worked in a prolific manner, with multiple pieces being worked on at various stages. I think that’s partly because I can be impatient but also because I walk in my parents’ footsteps and have a strong work ethic. The technical processes associated with printmaking reflect my methodical nature; however, I also love the immediacy and freedom of standing in front of a canvas with paintbrush in hand. The department lecturers that influenced me were Alberto Garcia-Alvarez, Denys Watkins and Paul Hartigan.

I’ll never forget the sight of those first red dots beside my works.

Leading up to my fourth-year undergraduate show I finally felt I was beginning to speak my own visual language. Realising I needed more time to evolve and develop, I did one more year of postgraduate study. In 1995 I took out my one and only student loan to pay for a pile of materials and then embarked on a body of work for my first solo exhibition at The Lane Gallery. The 90s really were the heady days of contemporary Pacific art. Everything was fresh, new and exciting. The market was buoyant and sales were regular. I’ll never forget the sight of those first red dots beside my works. The realisation that people were interested enough to buy my works prompted me to go ‘all in’. After graduating I balanced my studio days between managing a picture-framing shop in Ponsonby. After a few years in that role, and with sales steady and demand growing, I made the big leap and became a full-time artist. Newly married, overseas travel beckoned in 2000 and, beyond that, a decade devoted to raising my three children.

Fast-forward to today, I’m often asked what made me enter teaching. The real talk says income security over the fickleness of monthly art sales. The heart talk says motherhood changes everything, notwithstanding the major influence teachers and fellow artists have had throughout my arts journey to date. As someone who straddles both the creative arts and education sectors, I know visual arts education is a powerful platform for Pasifika students to embrace success as themselves. Thirty years later, and with ten years of art teaching experience, last year I embarked on a heartfelt research project to fulfil the requirements of a Master of Professional Studies in Education. I was interested in discovering whether students' experiences were similar to mine or if there was a significant shift in the way visual arts education is currently enacted for Pasifika.

From my secondary and tertiary (1986–1995) experiences, my success within the visual arts education system was grounded in the strong and authentic relationships with my educators. My ‘brownness’ was never mirrored in the cultural identity of my teachers or lecturers, but strong relations between teachers and students were significant factors in attaining educational success. Despite our education system’s commitment to Pasifika communities, a cry for action prevails throughout the fabric of our Pasifika arts community. Structural changes within research and teaching are necessary in order to make institutions more responsive to Pasifika. While there is also a lack of visibility, access and equity for Pasifika educators within visual arts education, my most meaningful and long-lasting teacher and mentor came from within my ancestral village. In 1993, in my third year at Elam, our father of contemporary Pacific art, Fatu Feu‘u, wandered unannounced into my studio. His actions, however, were deliberate. He asked about my name, ancestral connections and whether I would be interested in meeting other emerging artists of Pasifika descent. This act of recruitment, mentorship and collectivism was typical of the early beginnings of Fatu’s vision for contemporary Pacific arts.

Ercan’s village - Graham McGregor, Dagmar, Emily Karaka, Ercan, Alexis Neal, Barbara Ala’alatoa and Andy Leleisi’uoa - Grey Gallery Opening, October 2019

His visit was key for my growth given the scarcity of Pasifika resources (there was no Google back then!). My life-long relationship with Fatu exemplifies elder pedagogy. It offers to fulfil a prevalent gap in visual arts education, which affects the students’ access to Pasifika arts knowledge. Concerns surrounding the process of external examination remain (my story is sadly still being repeated today). The assessment standards and policies need to be re-evaluated in order to disrupt the current dominant discourse that measures creativity in terms of outcomes rather than in light of the emotional vulnerability inherent in conveying personal stories and experiences. In this way an acknowledgment of such actions would illicit more understanding of our personal and social contexts. Repositioning also needs to take into account the critical role that visual arts plays in enacting culturally sustaining pedagogy, since this field has the ability to sustain the ecosystem of Pasifika communities that have been historically marginalised and made invisible through schooling.

Through my research I realised that there is still important work to be done by Pasifika and non-Pasifika educators in order to address the persistent disparities in the educational outcomes for Pasifika. Here, a collective effort is required to challenge institutionalised racism and all other forms of discrimination embedded in national educational policies, practices and pedagogies. Time and space is needed to achieve such social change through honest, safe and courageous talanoa about justice and how education can disrupt discriminatory discourses.

The memories of my story have led me to ponder how different my life would have been without the critical support of an art teacher and the subsequent army of educators, colleagues and members of the Pasifika community who have championed my growth and development. In comparison, my 19-year-old son Ercan Cairns is already three years deep in his arts practice. He is embarking on his sixth solo painting exhibition, yet took no art subjects at school bar photography in Year 12. Purely self-taught, he told me, “School was so uninspiring, it forced me to go and find the thing I loved.” Ercan’s circle of mentors are some of my closest friends. They regularly check in on him, offer advice and attend his openings. Elam does not appear on Ercan’s radar because he already has a sustainable village raising him.

For both Ercan and I, our journey is not individual; it has and will always be kainga- and community-driven. As Pasifika, we are proud and resilient, since our strength lies in our collectiveness. My success is our success. When our foundations are strong, we are future proofing our very existence. My hope is that we, Pasifika, might produce a strong justice movement within art education in order to ensure such a worthy vision for our future generations that are yet to be realised.

cnz

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photo by Pati Solomona Tyrell.