Public Passions/Private Spaces

Sacha Judd reflects on the spaces we inhabit online, and how to create safe communities in the midst of the internet hellscape.

We exist to be in community with one another, a fact that’s never been so stark as we begin to recover from the forced isolation of the pandemic. Loneliness itself is reaching epidemic proportions. It feels so counterintuitive that, at a point in history in which we’ve never been more connected, so many of us feel so alone.

At first, the promise of the internet was utopian – a way to find like-minded souls unbounded by geography. To connect with people who cared about the same things we did, or identified the same way. The myth we bought early on was that a free and open internet would be a kind of global social and technological Eden, where everyone had a voice, and all the world’s knowledge was available to be exchanged. As Paul Ford writes, “People – smart, kind, thoughtful people – thought that comment boards and open discussion would heal us, would make sexism and racism negligible and tear down walls of class. We were certain that more communication would make everything better.”

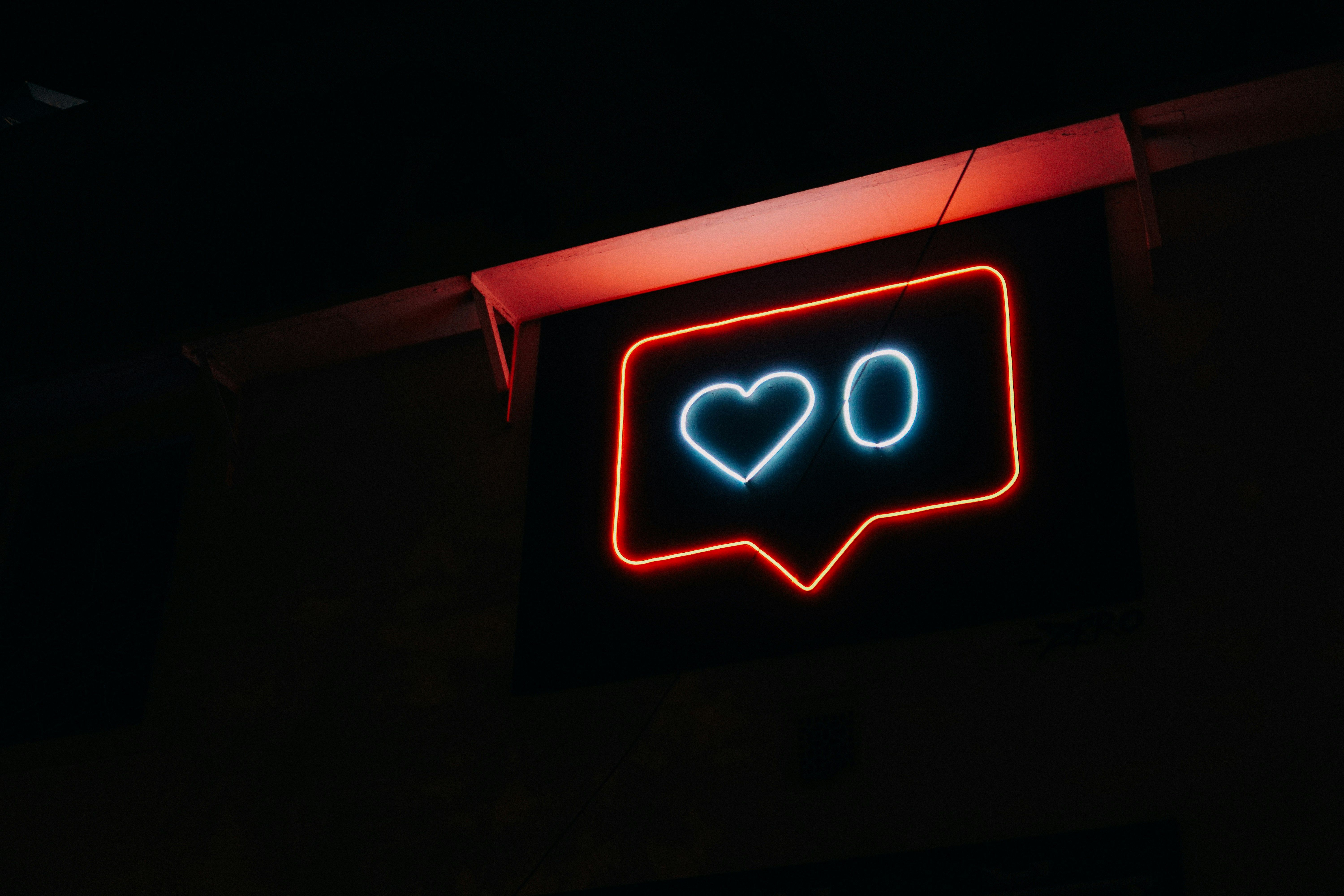

But, over time, the scale and growth of the internet made it feel less like a community and more like a busy city, and then eventually a hellscape. As the corporate owners of the platforms we rely on for our social infrastructure began to prioritise revenue and user numbers, they looked for anything that would increase ‘engagement’. And it turned out that animosity, outrage, anger and fear drove that more than anything else.

Even well-meaning people, who weren’t chasing perverse incentives, still clung to the libertarian ideal that all this interaction would inexorably lead toward social progress. I understand that urge. I grew up as a competitive international debater, and spent my teens and 20s completely convinced by the ‘marketplace of ideas’, the rationality of people. That sunlight was the best disinfectant. Of course the answer to bad information should be more information.

But instead, over the last decade we’ve had to grapple with a horrifying rise in misinformation, racist and supremacist ideology, and dangerous conspiracy thinking. The marketplace of ideas has just proven that unfortunately there is a market for truly terrible ideas. It turns out the devil didn’t need any more advocates.

The more interesting question is: What can we do next?

Over time, the scale and growth of the internet made it feel less like a community and more like a busy city, and then eventually a hellscape.

So much of this comes down to the spaces we carve out for ourselves. The internet pushed everyone together online in a single common forum in the span of a generation, something we were never designed to cope with. I think often about Dunbar’s number, the cognitive limit to the number of people we can have stable social interactions with: 150. Within that, in the offline world, we create nuanced circles of people we know – workmates, old school friends, crushes, professional networks. We deal with each of these groups of people in different ways, code-switching between them, sharing more or less of ourselves as feels appropriate. Now, in the same way that a city feels cold and isolating until you find a space to make your own – a neighbourhood group, a dive bar, a dog park, a book club – we have to carve spaces for ourselves on the internet that feel warmer, safer and more manageable.

This can be small: the rise of the permanent group chat starts as a way to keep your extended family updated, to plan a weekend away with friends, but the little circle sticks. The messages keep flowing. It becomes a tiny community in your pocket. And for people from marginalised backgrounds it can be a lifeline – a little breathing space with people who understand you in an offline world that often doesn’t.

It can be intentional: industry Slacks for networking and connection, or Facebook groups about a podcast you listen to. Discords set up to chat about hobbies, games and fandoms. A Substack comment thread about a newsletter that you love.

And these spaces – carved deliberately, shared only with like-minded souls – can feel nostalgic. They feel like the early internet, when there were far fewer people online. There’s a sense that you can let your guard down a little more. And because everyone has chosen to be there, no one will be quick to leap to a bad-faith interpretation of what you have to say.

But there’s a challenge with these spaces. The tools we’re using weren’t made with these purposes in mind. At first, you don’t notice the problem, because the community has chosen to come together around a shared interest. But as a fandom Discord, or an industry Slack, grows to have hundreds or even thousands of members, it essentially becomes a public space again. But without any of the curation tools that we need. You can’t block people, or mute people, because that’s not what the tools (built for workplaces or one-on-one communication) are for.

So we try to shape these spaces. We appoint moderators, we set up codes of conduct or rules for the group. And where do these sets of rules always start? The first rule is almost always to be polite to one another. Or that we should “assume everyone has good intentions”. Inevitably, from here we leap to “not making discussions political” as some sort of proxy for “making everyone feel welcome”.

These spaces – carved deliberately, shared only with like-minded souls – can feel nostalgic. They feel like the early internet, when there were far fewer people online.

These seem like admirable sentiments – but the reality is that they’re a proxy for a uniformity of thought that can sometimes have unintended consequences. Consider some very different examples.

A Harry Potter fanfiction Discord, bringing together fans of the famous book series who create transformative works of fiction and art. Like many fandom spaces, the entry rules are expressed to be as inclusive as possible. “Don’t be rude.” “Treat others with respect.” But these can quickly devolve when someone raises an issue that the community more broadly might be uncomfortable with. Are the depictions of certain characters in the books racist? Is it possible to grapple with the author’s very public transphobia and still enjoy the works she’s created? Is writing about romances between characters of different ages ‘problematic’? Civil debate devolves as participants dig their heels in. Server rules are changed to prohibit “fighting and argument for the sake of it”. Discussions are closed down. Dissenting members leave. As fandom scholar Rukmini Pande says, “They can kick you out of a chat. They can kick you out of a Discord. A lot of non-white fans are saying, ‘I’m not really comfortable with going into a Discord where the premium, once again, is on niceness, … on not rocking the boat.’”

There is also something specific to the nature of public online spaces that can allow someone to speak without interruption. I started thinking about this dichotomy (between public and private spaces) a couple of years ago as I read this great article about racism in the knitting community. Instagram is a place where fibre artists can share their work and create spaces for inspiration and knowledge sharing. In this case, after a particularly tone-deaf post from a white creator, knitters of colour used Instagram, and specifically Instagram stories, to share their experiences with racism in the community. Hundreds of people of colour shared stories of “being ignored in knitting stores, having white knitters assume they were poor or complete amateurs, or flat-out saying they didn’t think black or Asian people knit.” Instagram stories are ephemeral, disappearing after a period of time, and there was something in that ephemerality that freed people up to talk about the topic. One of those who participated said, “I don’t think this conversation could have happened elsewhere. There just isn’t another place where you could have this community, somewhat uncensored and able to react to one another.”

Then again, consider my neighbourhood Facebook group. A lifeline in the pandemic – sharing where we could get fresh vegetables from farm stands when the supermarket delivery slots dried up, and letting neighbours know when one of their cows had escaped onto the highway. The official description is “Locals, Community and Businesses” – a place for events and announcements – but during the pandemic it became a hotbed of anti-vaccination misinformation and anti-government protest. The admin added a new rule: “No Covid posts, pro or anti” (arguably the only “pro-Covid” people were the ones refusing to get vaccinated) and yet the daily torrent of misplaced anger and conspiracy mongering continued. The admin, refusing to be vaccinated herself, instituted another new rule: blocking her would get you kicked out. A neighbour said to me at one point that she kept thinking of starting another group, but felt like it was just too much work. I’ve left the group in fits of pique and rejoined about three or four times now. During Cyclone Gabrielle it was the only place with reliable information about road closures and power outages, so I put up with the noise.

There’s no such thing as a neutral space. A decision to have an apolitical community is an inherently political decision.

These are, unfortunately, extremely contradictory ideas. Messy, unmoderated, public spaces like social media are terrible for underrepresented voices because they get harassed, drowned out and driven away. But structured, moderated, controlled spaces don’t allow underrepresented voices to call out racism, transphobia and misogyny without asking anyone for permission. And where the people in charge are the ones spreading the falsehoods, there’s very little you can do.

There’s no such thing as a neutral space. A decision to have an apolitical community is an inherently political decision.

I hate the idea that we’re giving up, though. That we’re ceding our public square to the Nazis and the trolls. I’ve thought a lot about things we can do to fight for those common spaces.

Firstly, we need laws and regulation. Whenever humanity has invented new forms of media in the past, regulation has had to follow. Radio, television, telecommunications. It’s never been the case that we’ve said “share your message with hundreds of millions of people, unimpeded” – we’ve had standards, and we’ve had licensing, and we’ve had rules. We need effective antitrust legislation that prevents monopoly power from resting in the hands of a tiny few private companies that we rely on for almost everything. And crucially, we need law enforcement agencies who understand the ways in which technology is weaponised, coupled with rules around hate speech and online harassment.

Second, we need to learn the lessons of the last ten years. We now have good data that shows us that platform trust and safety policies are effective. And we have seen the real-world effects of Twitter’s new owner dismantling the trust and safety team at that company, with horrifying results. The reality is that a small number of hostile users are responsible for all the bad behaviour in an online space, and removing them works. Is real human moderation easy? No. But it turns out we can focus on a small subset of the problem and have an outsized effect: When Telegram was banned in Brazil, due to the spread of misinformation ahead of presidential elections, one of the changes it made to have the ban lifted was to have employees focus on the top 100 channels, responsible for spreading 95% of the public posts in the country.

But I also think we need to act local: to focus on building great neighbourhoods, instead of giant venture-capital-funded platforms. To forget about finding the ‘next Twitter’, and instead invest our time in places where we share the things we love online, not for clout or influence or likes or clicks. Sharing our favourite things is a love language. Sitting around in front of the TV showing each other our saved clips on YouTube or messaging our friends the best TikToks we’ve seen that day. Our platforms and social infrastructure should feel like that. We need to stop being misled by the algorithms, and get back to the things we’re passionate about.

Ayesha Siddiqi wrote in her newsletter:

The effect of the internet on the world doesn’t uniquely harm the world as much as it exposes and amplifies what was already wrong with it. Racism, sexism, misinformation ... The internet accelerates and it fills in the gaps. Nothing that’s gotten worse in recent years was something new or unprecedented – it all had historical points of origin. Meanwhile, a lot of what is better about the world now is new. It is unprecedented. We’ve made so many gains.

And every genuine gain facilitated by social media I credit to people, not platforms. I credit it to people building digital alternatives to what was missing in the physical world; spheres of influence, access, connection, empowerment. I think of people who made it possible for sexual violence to have social consequence. I think of the students using Discord to organize school walkouts. I think of all the people getting help through therapists posting on Instagram and life coaches on TikTok. Sure, the quality varies, but that’s true of the healthcare system too. ADHD and autism is under-diagnosed in girls and people of color. These individuals have been better able to access life-improving guidance online. Some of the best culture writers today came up on Tumblr and Twitter; we would’ve missed out on so many valuable perspectives without them.

The truth is none of us is part of only one community. We’re part of rock-climbing groups and improv troupes and choirs. Writing workshops and gardening groups and pottery classes. And I firmly believe that the online networks and spaces that we’re part of that are healthy and inclusive and happy places to be need to show up the places that are toxic and broken to the point that people won’t want to be a part of them anymore.

I believe that our good neighbourhoods can influence the bad. I have hope that the things we gain by finding our kindred spirits online will outweigh the messy, difficult, hard work of building spaces that we enjoy. The thing I love most about the internet is its ability to bring us together. Vibrant communities of engaged people connecting around the things they love. It’s up to us to carve spaces that we’re proud of; spaces that we’re delighted to share.