Plastic Fantastic: The Endurance of the Tupperware Party

They're seen as the stuff of 1950s housewife kitsch, but Tupperware Parties - "making a difference to the lives of women for sixty years" - are still happening right now, even in Auckland. And they might even serve a social function. Jessica McAllen investigates.

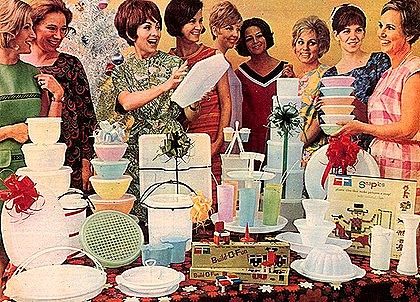

A 1950s promotional advert for Tupperware

Normally, people know not to invite students to events which are founded on the premise of spending more than $10 on a bottle of wine (or anything else). Why? Because we are cheap, tight-pursed scavengers. If an item can’t be found at the Warehouse, it’s not worth owning.

And Tupperware? We already have Tupperware, of sorts. Shoeboxes, tinfoil, left over party cups – even some actual Tupperware, stolen from family dinners under the ruse of storing leftovers, mysteriously unreturned.

But my flatmate rang me in desperation just as her first Tupperware party was about to start: “I need an eighth person,” she begged. “Or I won’t qualify for the reward.”

Could I really live with the guilt of denying her free stuff? Probably, but I can never turn down chips, dip or free whiskey.

Tupperware made its debut in 1946 through American businessman and inventor, Earl Tupper. The products were deemed revolutionary (no one had quite figured what to do with the weird looking, weird smelling and relatively new material of plastic in the domestic setting) and Mr Tupper’s bright idea to create airtight seals was a genuine gamechanger. Space-age boxes prevented food from drying out and wilting. The future was now.

There was only one major drawback: it was hard conveying to a potential customer how to work Tupperware without a trained team member performing a live, hands-on demonstration. As a result, in 1950 Tupper pulled his products out of retail stores and passed the task of marketing onto Brownie Wise – who had been hosting Tupperware parties at her own home for years.

In Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century, historian Stephen Fenichell writes about what happened next - the “kitchen kinkiness and object fetishism” that turned Tupperware parties into a classic post-war social activity:

Tupperware parties superficially operated as quasi-social gatherings, the ideal way for a young, socially self-conscious house-wife to widen her claustrophobically small circle of friends. More covertly, they gave thousands of hard-headed fifties house-wives with an insatiable zest for home economics an opportunity to safely fuse entrepreneurialism with the traditional social obligations of home entertainment – and improvement.

The parties proved to be a very successful way of communicating the benefits of Tupperware and earning some cash on the side. By 1951 the system of baking and boozing away money on plastic had worked so well that all Tupperware products were taken off shelves to be distributed via parties (although these days, you can get them online too). In 1953, sales topped $25 million.

So here we are, 65 years later, with a seemingly thriving Tupperware Party culture, even in New Zealand. And there I was, at 21-years-old, willingly reverting to the role of a 1950s housewife and admiring overpriced plastic to help my flatmate.

Hosting a Tupperware Party sounds daunting but the rules are really very simple:

- Invite people to your abode under the false pretence of a party and have them listen to a lady ramble on about products they probably don’t need, want or can buy for a lower price at any number of shops.

- Play games that would not be out of place at a 3-year-old’s party to lure guests into a false sense of security.

- Receive free Tupperware as a reward for extorting a large amount of money from your guests.

Our host was Fleur. She earns around $150 for every Tupperware Party she demonstrates at. She was bubbly, friendly and firm – the kind of person I imagine would make the best lemon meringue pies and always be up for a spot of Canvas-sanctioned Sunday brunch.

She also addressed all of us as “ladies”.

This would normally not be a problem if we were, in fact, all ladies. However, out of the eight of us three were men. I’m not sure if Tupperware Brands generally clings to this idea that the plastic products can only be for women – in 2013, their tagline on the website talks about “making a difference in the lives of women for over sixty years” – but I sure think it might be time to realise men can also enjoy the art of Tupperware (in fact, the ones at this particular party all made purchases).

Despite Fleur acknowledging and bantering with the men in the room, she continued to insist on calling us all ladies the whole night, as if she was sticking to a script. I noted down four instances until she started suspiciously eying my university notebook – it’s easy to get distracted if you don’t find Tupperware particularly exciting.

Demonstrators, such as Fleur, are not the only ones who profit from these parties. Since my flatmate was ever-so-kindly allowing the party to be hosted in our house, she could qualify for some free products. The catch: at least eight people had to have attended the party, two friends needed to agree to host another one and we (the obliging guests) had to depart with a certain amount of money.

Our target was to spend a mind-blowing total of $500 on Tupperware so my flatmate could get a plastic present set. Alternatively, if we hustled up $750 then she could get some of the popular (and admittedly quite pretty) bowls.

“It sounds like a lot, but it really isn’t that much money,” Fleur beamed.

There was a brief presentation on the hidden talents of containers (they keep stuff fresh and can be stacked in a fun “Lego for ladies” type of way) and a mortifying game where we had to steal mini Tupperware off each other (everyone wanted the mini spatula, not many could figure out what the “olive pick-upperer” was).

Finally, the night got onto what I was really there for. Fleur picked up the spirits and – never one to miss a tie-in opportunity – started to whisk up cocktails in a Tupperware bowl.

This is where the moneymaking aspect really kicked in. Using alcohol to help ease sales – sly, but ingenious. Maybe department stores should follow the Tupperware ladies’ lead and offer a couple of pints when customers are deciding on purchases. Maybe this is why there aren’t so many bars in shopping malls. Either way, it was starting to feel like Fleur might be waiting for our inhibitions to slip in the hopes we would tumble into a Tupperware taxi with her at the end of the night.

We were introduced to the family-friendly Tupperware can-opener, a steal at $69. The person who invented this clearly forgot about the ‘when in doubt, whip a knife out’ policy, or at least hoped that enough potential customers had.

“It creates a smooth cut,” Fleur pointed out, “without any jagged edges. And left-handed people can use it.”

Next on the agenda was the ‘Vent Smart Set’, a bundle of boxes to put in your fridge to replace standard drawers (which are actually called “food coffins” by those in the Tupperware know). We were lectured on how the average household throws away about $20 a week in rotten food. Instead, we were advised to make a wise life investment and buy these boxes. Each set has a tight seal that lets produce “breathe” and comes with adjustable switches for each products’ individual airing needs.

Pineapple, cucumber, celery, strawberries and turnips are all “light breathers” and go into a container with the switch at a certain level. It all sounded so awfully scientific, and I had been drinking cocktails on an empty stomach. I nearly caved.

But it was $273.

As the night came to a close, the level of tension and embarrassment was on par with a failed charity auction – we were just off the amount of money required for my flatmate to get her Tupperware prizes. Desperately some people offered to buy rice-cookers, steamers, anything, but we realised it wasn’t going to add up. And I awkwardly sat there, writing in my notepad and feeling horrible about not having enough money to try and help her get that coveted prize. Sheer oddness of the night aside, I knew she had been drawn to the party because she really needed new kitchen items and it seemed like a fun way to get some.

But then I wondered why I was feeling so bad. It’s not like I would ever really use any of this stuff. First alcohol, now guilt? No wonder Tupper’s industry is still raking in money.

My flatmate later admitted she felt a bit uncomfortable asking her friends to buy Tupperware so she could get something for free, but that she enjoyed the night. Others agreed in the conversation we had after Fleur left (it was a massive relief to see that permanently-happy face out my front gate, never to brighten my door again). Fellow attendees liked Fleur’s bubbly nature and that they were able to make time to meet up in their otherwise busy schedules (one of our friends had just come straight from her hospital job in full attire).

Over 60 years ago, Tupperware parties were an escape from the dreary life of house-wivery, a chance to exchange the husband, kids, chores and expectations for a sly drink with friends while completing the transition to ultimate domestic goddess. Perhaps this is why the parties are still going strong in 2013: for a certain group of women who needed it, they were the original social media platform. Although our party saw more jeans than pink-frosted pinafores, the element of escapism remained – away from employers, lecturers and most importantly, our modern life; a fleeting moment of nostalgia and an attempt for the perceived sophistication of our foremothers.

The items for sale at these parties are not necessarily low-quality tat. In fact, they’re undeniably useful if you find yourself with an overwhelming desire for compartmentalising each carrot and celery by colour. Representatives, like Fleur, may rely solely on the income they make from sales. But the high-pressure sales tactics aren’t exactly seamless. And in this domestic setting, everyone who’s been loved must be left.

Future Tupperware parties have been planned, so it can’t have been all that bad for everyone else. However, I declined. It’s nice seeing your friends but I’d rather watch a movie with them than have a walking, talking, and mini-plastic-spatula brandishing infomercial take place in my own lounge.

Personally, the end of the night felt like a classic one night stand. Fleur packed up her table, whisking away the enticing plastic and leaving us alone. The next morning was the kind of hangover headache that’s compounded by spending too much money the night before – but this time regret came from the vessels, rather than the drinks themselves.