Peter Hawkesby: Dance Moves at the Clay Table

Elle Loui August on the artists' triumphant return to the kiln

Elle Loui August on the artists' triumphant return to the kiln.

Even before Peter Hawkesby closed the doors on the St Kevin’s Arcade café Alleluya in December 2015, talk had begun to circulate about a turn back toward ceramics. Peter had been seen at work out at Auckland Studio Potters collective in Onehunga, had been slipping things into the kilns of fellow potters about the city, was even, it was rumoured, in the process of firing up his own out on the grassy slope at his Newton villa. When Scratch a Cenotaph opened at Anna Miles Gallery in 2018, it arrived on a tide of expectation, sating a wellspring of curiosity and respectful speculation.

Long a familiar figure seen cutting a path along Karangahape Road, as proprietor of Alleluya, Hawkesby had fostered a distinct and beneficent sensibility. The ambient glow of the arcade’s tall windows had cast a Kodak-toned hue over what might be best described as something of a communal living-room, somewhere between domestic and bohemian in character. Hawkesby’s trademark good humour, combined with the generous girth of the architecture, provided the opportune conditions to foment a place of welcome. Indeed, over the 20 years of his tenure, Alleluya became an important gathering ground, frequented by artists, writers, workers and waifs, often playing host to a range of extracurricular social gatherings, performances and events. Films were made, dance evenings hosted, songs and laughter ringing out along its spine.

Less known during these years – even to many who frequented his establishment – was Peter’s own renown as a ceramic artist. With hands immersed in the daily operations of a small business, his own making practice had gone into something of a hiatus, or, rather, had been pushed into deeper, longer and slower ruminations. Scratch a Cenotaph gestured knowingly to this thickening in the cycle of an artistic lifetime, taking shape as a series of small votive sculptures that traced a partial, biographical cosmology. A genesis story of sorts, each assemblage took title in homage to an individual, place or event that had shaped the artist during a critical period in his life, stretching as far back as his father’s military campaigns of World War 2 and his own self-protective strategies when coming out while a boarding-school boy in the Aotearoa of the 1960s.

...the story of Hawkesby’s sculptural sensibility sends its roots down to his early training in the fundaments and mechanics of the local tradition

Within this loosely narrative framework, immersed in the consummate riches of Hawkesby’s personal biography, it was the detailed fabric of the work that astounded, revealing a geological complexity to Hawkesby’s hand. Almost painterly in his approach, each altar-like form worked a finely tuned constellation of texture and glaze effect, bursting forth a compendium of ceramic references and experiments in kiln temperature. His lexicon of abstract motifs replete with titles – loops, ticks, screens, shields, wands, cloaks, tabs, tiles – and the unnamed ‘bits and pieces,’ were bought to balance in compositions of small-scale physical intensity. Wads of clay used to prop ‘serious’ pots during a firing reappeared painted in carnivalesque canary stripes, or simply raw, slightly kiln-stained and slipped under a slab. Loops encircled ticks, encircled other loops. Coils concealed wands. Perforations, slices and soda all did their work. The result was a resolutely singular language that, if anything, was more reminiscent of the ceramic collaborations of Joan Miró and Josep Llorens i Artigas than the more stately and familiar stoneware of the local ceramics canon. Nevertheless, the story of Hawkesby’s sculptural sensibility sends its roots down to his early training in the fundaments and mechanics of the local tradition. We might view his later experiments and iconoclastic dérives as providing evidence of what friend and gallerist Anna Miles refers to as the “rich DNA” that gifts a rigorous studio practice a compelling intrigue.

Training as an apprentice studio potter north of Auckland during the early 1970s, Hawkesby swiftly became frustrated with the established orthodoxy and folksy mores worked into the grain of the post-Leachian lifestyle. Over beer on the back patio of his studio, he quips, “It’s hard to imagine now, but at that time being a studio potter was quite bourgeois. You could live in the country, throw pots and drive a Volvo.” A resolve to pursue making with greater imaginative intensity, combined with an intuition that the material could go further – and take him along with it – drew Hawkesby back towards Auckland City in 1977, and to a new series of collaborations and relationships. Settling on Waiheke Island into a productive creative partnership with fellow potter Denis O’Connor, the two forged ahead in their idiosyncratic clay experiments. Sifting swamp clay out of the local mangroves and firing it to the limits of cohesion, disavowing wheel throwing in favour of the hand built, each immersed himself in the widest possible field of influence. Emboldened by a trip to the West Coast of the United States in 1978, where they encountered the work of Peter Voulkos, Ron Nagle and Michael Frimkess, among others, for Hawkesby and O’Connor this was a time of digesting as much as could possibly be gouged from the world, and then reconstituting it, irreverently, in clay. As O’Connor writes in his 1997 essay ‘Mud Company’:

Diverse as architecture, industrial or product design, street fashion, contemporary painting and Arte Povera, carnival floats, psychological identikits, etc... Music, dance crazes, film, advertising and any low art source was the preferred focus of attention and appropriation, ‘ideas’ being the crucial component of these ceramic sculptures.

This productive time on Waiheke was followed by a period living on Prime Road in Grey Lynn, where the spirit of dogged investigation, and equal part irreverence, went with him. Sharing the home of Warren Tippett – another visionary outlier in ceramics, known for his chromatic experiments and vibrant glazes – it was through time with him, Hawkesby reflects, that he really learned how to ‘see.’ Tippett was an experienced and hugely industrious potter who had cut his teeth living the back-to-the-land lifestyle loosely prescribed by the studio pottery movement of the time. In Grey Lynn, Tippett was renowned for his backyard pottery sales that would see hundreds of interested buyers traipsing through their home in periodic bursts, seeking out his painterly vessels. This was an energetic and expansive period for Hawkesby, making like mad and establishing lifelong friendships within a community of fellow artists and like minds, including performance-maker Warwick Broadhead, writer and filmmaker Peter Wells and art historian Roger Blackley. Making during the weekdays, and then lugging boxes of work over to his kiln on Waiheke to fire in the weekends, Hawkesby continued to refine his oeuvre. Vessels, vases, mugs, beakers, spouted porcelain teapots with precarious-seeming supportive struts, all rendered in a soft array of glazes and surface mark-making in which pinks, browns, indigos and greens predominated. Some of his trademark groupings that began on Waiheke – with evocative titles such as the Blunted Devil Cups and the stubborn, earthy Incinerators – continued to accrue further company until suddenly, with a change in the wind, Hawkesby left to live in Japan, ostensibly bringing this period of great productivity to a close.

When I visit collector, curator and ceramics writer Richard Fahey, he slips an early mug of Peter’s into my hand. It’s a piece hailing from this early period, and it’s an odd thing by all accounts. Slab built, with a counter-intuitive curve and slight sag, yet it is in no way the work of an amateur. For a utilitarian object, it is strangely stirring. A handmade, useful thing in which a multitude of imaginative sources can be felt. Fahey is one of Hawkesby’s greatest supporters and has, over the years, taken on the role of being something of an unofficial archivist and informed provocateur. In 2011, he curated a small survey of Hawkesby’s early work that was hosted within the larger exhibition Playing with Fire, held at the University of Auckland’s Gus Fisher Gallery, and he has written about Hawkesby’s work for a number of public forums. For Fahey, it is Hawkesby’s highly skilled and knowing diversions from ceramic propriety that captivate. With his imaginative and charged "bodily" propositions, Hawkesby, as Fahey sees him, is not only expanding the subjective lexicon of local clay practice, but also offering rich and knowing incursions into the fabric of the practice itself. A generative conversation of the hands, so to speak, keeping in contact with the histories of the medium and offering a feast for those who know how to read what they see, or find themselves compelled to try.

In the window, lined up in front of a darkly drawn curtain, Fahey found the strangest, most compelling clay ‘things’ he had ever come across

Fahey recounts his first encounter with Hawkesby’s work as a welcome and thrilling smack in the guts. While an art student in the Waikato, he had been tasked with bundling up anti-apartheid placards and delivering them to the then-hub of Auckland’s anti-tour organising, The Potters Arms, on Dominion Road. In the window, lined up in front of a darkly drawn curtain, Fahey found the strangest, most compelling clay ‘things’ he had ever come across. Cousins of the Incinerator and Blunted Devil Cups series, these were raw, club-handled objects punctuated with triangular perforations and raised jagged teeth that Hawkesby had simply titled Weapons. Made after an unfortunate brush with young street fighters in Christchurch, these objects were Hawkesby’s response to a darkening cultural background in which “the riot squad had fully morphed into these dangerous creatures with batons.” Speaking retrospectively on the impact of these works, Fahey reflects on Hawkseby’s prescient ability to mirror the fervent atmosphere of the time.

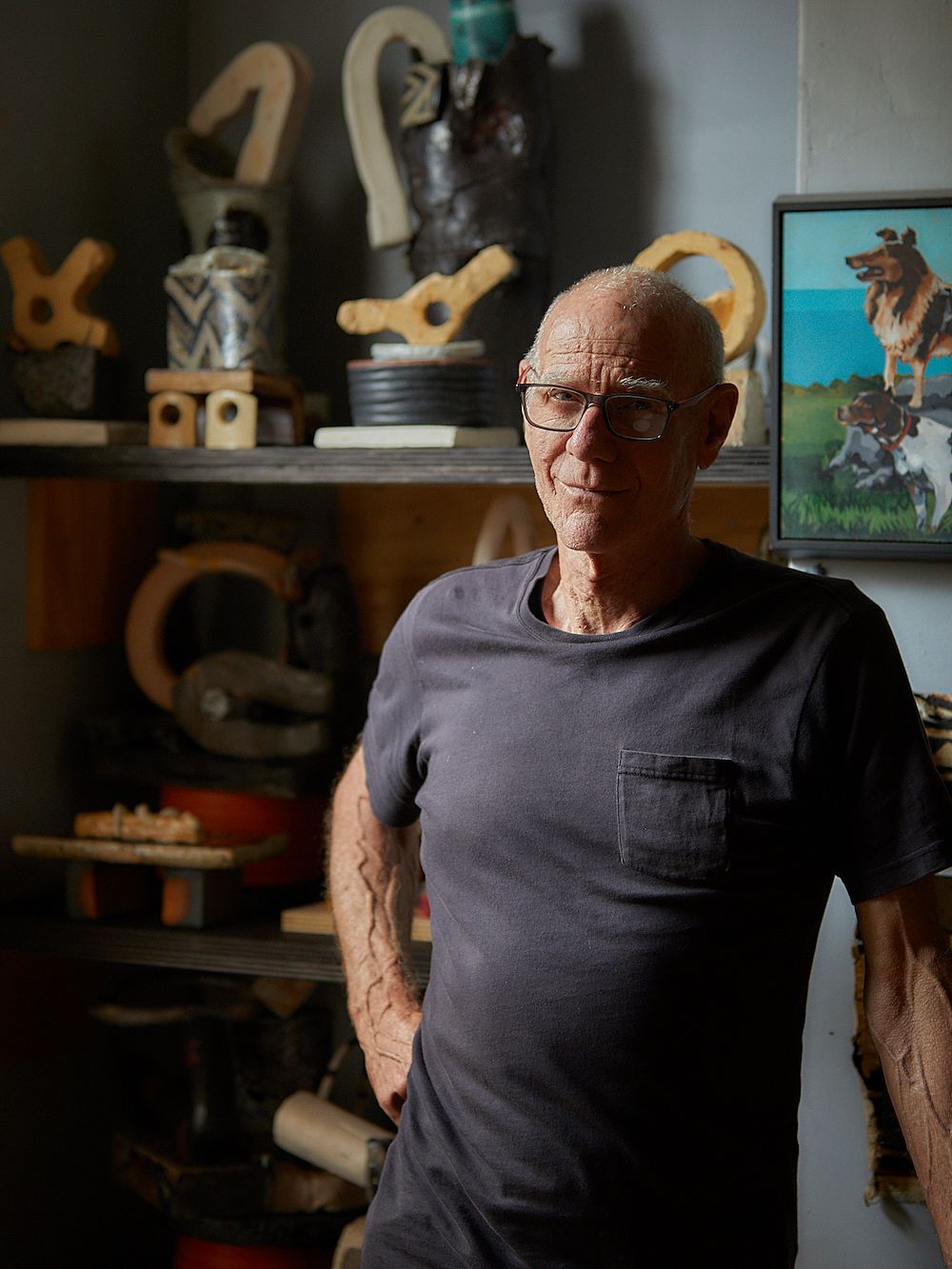

To visit Hawkesby’s home studio now is to enter into an engine of imaginative productivity. New works jostle for space on shelves and walls spilling with the works of friends and contemporaries: Browynne Cornish’s archaic ceramic figures, paintings by Richard McWhannell and Seung Yul Oh, photographs by Alan McDonald, a painted backdrop from a performance by Douglas Wright, an early collaboration with Kate Newby, among numerous others. It’s the kind of art historical microcosm we see too little of in our public galleries; visits like this remain one of the greatest pleasures and privileges of this writer and exhibition maker’s job. At the centre of this lively commotion is the ‘new’ work that is currently underway – although the term ‘new’ is not quite right here, given the complex processes of unearthing and re-digestion that Hawkesby is currently concerned with.

Over a number of weeks, I stop by his studio several times. On the first visit, a large shelf is loaded with freshly bisque-fired saggar pots waiting to become the bases of new sculptures. A series of recent teapots lines smaller shelves, and another work-in-progress rests on a lazy Susan on the table. By my second visit – with a young aspirant ceramicist in tow – a new body of vessels developing on some of his much earlier vase forms dominates the cabinetry. Given the nominal framing of Snowflake Kimono Vases (2019) these are graceful, finely balanced, double-layered cylindrical forms that display Hawkesby’s command of a quieter compositional register. Recently made Blunted Devil Cups are wedged in tightly together, assembled on bases of hatched tiles or semi-squashed up Loops. One in particular that takes my eye is piled up on a nub of porcelain intestines. At this point in the summer, Hawkesby has been making the most of the use of Emily Siddell’s kiln while she is away from the city, and with characteristic generosity, he talks my young friend through the nuance of different kiln environments, his experience of the characteristics of salt versus soda firing, and takes us out to visit his own gas-fired kiln, Augusta, built beside a sprawling fig tree in the backyard.

By my third visit, the abiding velocity has taken Hawkesby in all new directions. Following a spell of ‘mudlarking’ with Mark Goody and Siddell out on the site of an old clay works in West Auckland, Hawkesby had begun to incorporate found objects with greater abandon, using these as a springboard for the development of a range of sculptural themes. Having previously dug into his own back catalogue – in one instance, quite literally digging up old pieces buried under his sister’s compost heap – processes of dismantling, re-firing and reworking older fragments have been intrinsic to his method. The use of found ceramic and concrete objects, however, is a more recent turn for his practice. One series of new works draws heavily on the found forms from the West Auckland site, while another reworks ideas drawn from these objects which he then remakes and adds into the fray. I laugh out loud when I walk through the door on this visit, astounded by the almost impossible developments that have taken shape in such a short period of time. “I’m in a kind of paradise,” Hawkesby tells me, “looking through all of these local antiquities. Old Auckland bricks and sewage pipes are absolutely exquisite when looked at in another way.”

He pours me a cup of tea and I sit on the floor to look closely at some of what is going on. A u-shaped pipe fragment balances on a concrete plug with a quavering low-fired loop cutting across its top, two wing-like circles keeping it all afloat. Compositions of found, fired fragments are in a tumble with low-fired white raku and recycled clays wrought in circles and loops. The saggar pots have all metamorphosed into small, vivacious sculptures, totemic gardens with parts titled smell valve, cogs and venetian blinds, another plate-like form is dubbed a radioactive fruitcake. Each of these titlesoperates like a hook, drawing one into a roaming ferment of ideas that slide about wilfully. Autobiographical references still provide leaping-off points – there is a series of teapots named after a dowager Aunt (Minzy) and a small votive offering to the late writer and filmmaker Peter Wells.

The spectrum of emotions, tones, characters and narratives here is as wide-ranging as the textures Hawkesby uses to render them. Resplendent among these new works are the provisionally titled Crowded Shinkansen and Hauling a Moon. Both are evidence of the increased complexity Hawkesby’s practice has gained over the recent summer months. There are quieter works too, Saint Hangaround and Nani’s Light Touch use simple acts of balance and framing to allow the suchness of each component to sing. Indeed, it wouldn’t be a stretch to refigure Hawkesby’s studio scene as something akin to a clay chorus. These are all works of ecstatic determination, each crafted with devotion to the fineness of the small and the polyvalent resonances inherent in human-made forms. All notes honoured, their relations running true.

This piece is presented as part of a partnership with Blumhardt Foundation. They cover the costs of paying our writers while we retain all editorial control.