A Patriarchal Parade: Sexism in Aotearoa New Zealand Literature

In a searing, articulate and informed essay, Vaughan Rapatahana takes Aotearoa New Zealand literature to task for sexism.

In a searing and articulate essay, Vaughan Rapatahana takes Aotearoa New Zealand literature to task for locker room schoolgirl-grooming, women-baiting, and sexism that arises from a violent and suppressed masculinity.

You, being a modern poet

Must write real he-man stuff

So you will take slabs of prose

And cuts it into chunks like this;

There need be no rhyme nor reason in it …

No top-notch New Zealand poet any longer

Writes ballads like Jessie Mackay

Or bird-songs like Eileen Duggan

Or lyricisms like Helena Henderson

Or tree-poems like Nellie Macleod …

And anyway they‘re only women

('Without Malice' by Alien in O’Leary 179-180).

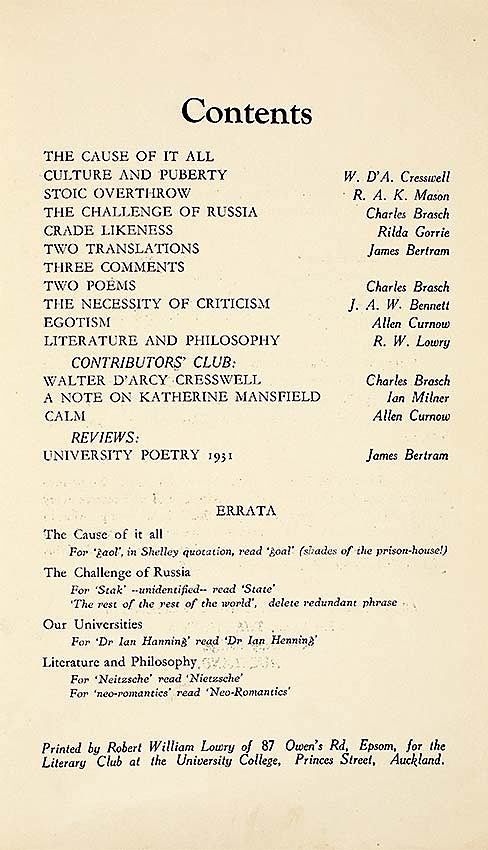

Introduction, an historical overview

Yes, I have read all the books, all the pertinent material pertaining. New Zealand has always been a sexist society, a patriarchal panoply of male power, controlling and suppressing female prowess – as so well exemplified in its literary structures. Sexism in literature is a reflection of a wider societal sexism whereby a deliberately constructed literary masculinity ruled up until the 1970s or at least the 80s. Historian Jock Phillips pronounced in 1987 that ‘the traditional male stereotype is now weakening in New Zealand’ (289), while academic Kai Jensen pronounced, ‘…the mid 1960s…was the end of a thirty-year sequence of growth, dominance and decline in what we may call “high masculinism”’ (107). While the latter admitted to some continued sexism in New Zealand Letters from male writers after this time, it was now, ‘a tenuous residual presence’ (157).

Poet Michael O’Leary in his excellent and well-resourced PhD thesis castigated male attitudes towards women writers in the time frame he designates as 1945 to around 1970, via their deliberate masculinist conspiracy to subjugate them. He states:

Through examining the detail of selected writers’ lives, it is possible to understand how their exclusion was systemic rather than individual, and how the prevailing structures of sexism, racism, classism and homophobia worked to normalise the prototypical great New Zealand writer of the period as invariably male, white, middle-class, and preferably with direct experience of bloody and violent war service (169).

Earlier in his thesis O’Leary had specified:

The evidence presented…suggests that the women poets of the post-war era, from 1945 to 1970 were disadvantaged simply by being women…Remarks by many of the male poets towards women writers cannot be shrugged off as mere playfulness or banter but it may be argued that they portray a distrust and misogyny within the male literary fraternity. Because the male writers at the time were also often the editors and publishers of the literary magazines and journals, and therefore the gatekeepers of style and content, their attitudes towards the women poets and writers affected whether those women were published (75).

Yet, O’Leary seems to surmise that by the 1970s such obvious marginalization of women writers in New Zealand and the even more obvious marginalization of ngā kaituhi wahine Māori rāua ko takāpui (Māori women and lesbian writers) had abated considerably. ‘Thus, this thesis has explored the constraints that delayed and inhibited the work of a gifted generation of women writers, some of whom were recognised in the post-1970s period after [the] second wave [of feminism] had successfully removed some of the barriers to women‘s full participation in the cultural life of New Zealand’ (169). O’Leary clarified this somewhat arbitrary guillotine point as coinciding with ‘the development of the feminist movement in New Zealand’ (v), and notes that this by no means meant the end of the sublimation of women writers in New Zealand.

I beg to differ considerably with such a naïve and spurious conclusion: there is no room for misogyny anywhere.

Even academic Lawrence Jones extended a long pointed finger at earlier 20th century misogynists and implied that this situation was no longer so – that this gender power imbalance was simply symptomatic of a rather long ago relic, namely ‘a coherent, conscious, revolutionary literary movement’ as centred by the ‘Phoenix-Caxton writers’ of the 1930s (426). Worryingly, however, he felt that such 20th century literary misogyny was still somehow excusable. He wrote earnestly, ‘But if it is a limitation, it is not one that invalidates the movement’s primary accomplishments any more than say, T.S. Eliot's elitism and anti-Semitism invalidate his literary accomplishment' (427).

I beg to differ considerably with such a naïve and spurious conclusion: there is no room for misogyny anywhere. So I also take serious issue with academic Stuart Murray when he warbled in relation to this selfsame group of male writers:

Much of the strong element of misogyny that runs through the 1930s…should be viewed in this light of the national need to administer difference through strong oppositionality, and the continual fear of parallel and alternative national narratives that might exist. In the New Zealand context, these alternatives were often those of women (88).

No way, Jose.

Thus Fairburn, Glover, Davin, Mulgan, Sargeson (ironically and somewhat subversively given his homosexuality), Gaskell, Curnow, among several others, were all archetypal Kiwi sexists, as was Baxter – even given how Kai Jensen tried to explain away Baxter’s misogynistic gusts via a Jungian apotheosis, something which fellow academic Terry Locke just couldn’t do. Wrote Locke of James K. Baxter: ‘He was also, I think, deeply and problematically misogynistic’ (59), and then he goes on to quote evidence from the poem Pig Island Letters (2).

Yet, for Jensen, Baxter can be excused of any abusive sexism. ‘Was Baxter such a misogynist, that he filled his poems with monstrous women?…The impulse to read Baxter’s bawdry literally as “pornography” in feminist terms is the same mistakes that his critics have made…not realizing that all the figures in his poems stand for parts of the deep psyche’ (127-128; 143). I, for one, side completely with Locke here. No one can tell me that the following lines from Baxter’s 'Letter to Sam Hunt,' as included in his collected poems from 1979, have the remotest sliver to do with Jungean psychotherapy. They are out-and-out nasty-sexist and women hating:

Sam Hunt, Sam Hunt, Sam Hunt, Sam Hunt

The housewife with her oyster cunt

Have pissed upon what might have been

Lively, original and green…

The Pill, the Rags, the Summer Sale,

Put Venus and her tribe in jail

Till every fuck’s a coffin-nail

Baxter’s literary scion Sam Hunt, at least the young Hunt, certainly was also such a practitioner of sexism in many of his poems. Take a titiro [look] at this excerpt from ‘I Wanna Love You Too’ from 1982:

(I said) ‘before tonight is through

I will have made you little girl

A lover out of you

And girl, your mummy she’s no fool

So please no stories out of school

And what about this excerpt from an earlier poem, ‘Letter to Jerusalem 2’:

Could easily have made it with the chick

Who picked me up: I’ve little doubt

She’d very much fancy a denim lout –

A little tougher than her easy action

Husband who fails to bring her on.

In fact, such locker room schoolgirl-grooming and women-baiting – and the implicit disposability of them probably extended well beyond Hunt’s earlier poetry, especially if we bear witness to his 2008 selection of and introduction to Baxter’s poems where, ‘it is…a Baxter who has been turned by Hunt’s selection practice to conform to a mythology of himself which Hunt sympathises with and which has a particular 1970s colouring’ (Locke 59). The New Zealand masculinist tendency to mythologise their sexual prowess and potency and the associated diminishment and anonymity of women this incorporated, obviously extends well and truly beyond the 20th century. Just how far, I will soon expand on.

The New Zealand masculinist tendency to mythologise their sexual prowess and potency and the associated diminishment and anonymity of women this incorporated, obviously extends well and truly beyond the 20th century.

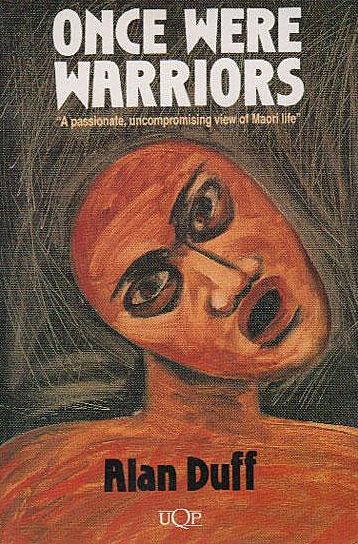

Academic Alistair Fox took a divergent approach to ‘explain’ New Zealand masculinities, whereby Kiwi men, especially novelists, are being dragged down by the past. He especially emphasized the discrepancy between two existentially disparate forms of masculinity and their inherent sexism – Māori and Pākehā – and the underlying causes as stemming from parental and cultural adherence to and inculcation of certain expected masculine ‘strengths’; thus a reluctance by men to talk about how they feel or even to show emotions. His is a psychotherapeutic approach to the themes and splintered male protagonists of several Kiwi male novelists, exploring in quite some proto-Freudian detail the immense discrepancies between what a New Zealand man is ‘supposed’ to be according to the cultural legacy he is raised into, and the way he actually feels himself to be, and what he may want and dream of.

Thus for many Pākehā it is a puritan work ethic which buggers them up, while for many Māori it is the so-called warrior culture they are ‘meant’ to have embedded in their genes: yet both groups struggle existentially to reconcile what they are expected to follow, with whom they essentially are. Fox stresses the double-whammy effect for Māori of having to somehow reconcile, ‘the imperatives of two cultures,’ whereby it is doubly difficult to achieve any ‘coherent sense of individuality’ (151). As Fox states, the difficulty is ‘being members of an indigenous minority who find themselves needing to square the values and imperatives of traditional Māori culture with those of a hegemonic post-imperial culture that is as powerful as it is alien’ (151). Tika [true].

For many Pākehā it is a puritan work ethic which buggers them up, while for many Māori it is the so-called warrior culture...

Fox’s analysis, however, is limited to only a few selected novelists such as Gee, Eldred-Grigg, Ihimaera and Duff, and rarely accesses a wider panorama of hegemonic colonialist, later globalised dominant discourses and constructs ascribing what a man ‘must’ be in the Antipodes. Nor does he consistently address the latent and manifest sexism of any of these authors, but rather their own latent and more manifest sexual dysfunctionalities.

Historian Brendan Hokowhitu accepted that Māori tāne were and continue to be well over-the-top as regards macho behaviour. He wrote well about how this was a learned, embedded ‘truth’ instilled in an entrenched discourse of Pākehā expectations, which required workers, war-warriors and sportsmen, so as to prolong the latter’s own white power. A self-fulfilling ‘regime of truth’ or ‘dominant metanarrative’ that commenced with British colonialist mythmaking and stereotyping about Māori men. Hokowhitu writes:

Ironically, many aspects of Maori masculinity now regarded as traditional were merely selected qualities of British colonial masculinity. In the hope of saving their people from near extinction, many tāne were forced to assume those masculine qualities that would abet their integration into the dominant Pākehā culture (269).

Therefore, Māori men became, ‘violent, stoical, rugged and sports-oriented,’ (Hokowhitu 269) in an effort to attain some sort of (limited) equality with white folk, given that the latter would never relinquish the reins of power. This Pākehā-enabled construct or ‘imagined reality,’ then, became an embedded routine for the very men it created an image of. Hokowhitu states, ‘Thus, the supposedly intrinsic violence of Māori males is naturalized and sanctioned within acceptable, colonized roles’ (264) – those of warriors in world wars, elite sportsmen, manual labourers.

Let me be clear here: Māori males may be categorized as being cast as marginalised masculinity, by the agents of an elite and potent white hegemonic masculinity, but this by no means prevents their violence, being ‘tough’ and insensate, as they internalized their mentor’s patriarchal attitudes. They may not have the political and socio-economic clout of (some) Pākehā males, but they still can use their fists, eh.

Māori males...may not have the political and socio-economic clout of (some) Pākehā males, but they still can use their fists, eh.

As is all-too-often fictionalized in the novels of a somewhat conflicted masculinist Alan Duff, who couldn’t decide if it was some naturally embedded ‘warrior gene’ or some nurtured genus that drove Māori males to sublimate their wāhine by the fist, a la Jake Heke. As academic Michelle Keown succinctly states, ‘Duff’s writing offers an ambivalent response to the ‘Māori warrior’ legacy, and his comments on violence within the contemporary Māori community are at times contradictory’ (105). Regardless of the genesis of such ‘disciplined brutes’ – and I believe Hokowhitu’s thesis to be correct – it is Jake the Muss who garnered the more massive profile across Aotearoa and beyond, than Beth Heke – as especially augmented by the grandiose filmic version of the original novel. What a Māori role model!

Brendan Hokowhitu again, regarding this deliberately constructed British

colonial apparatus designed for dialogue with Māori by means of physical statements, and to produce indigenous bodies recognizable through their natural physicality…Māori men were only allowed access to these arenas, however, because success within them did not oppose the dominant discourses underpinned by physicality ((a) 51).

It is no wonder therefore, that – after a deliberately designed limited rural schooling and the consequent urbanization of New Zealand – Māori men found themselves stuck in cities with ‘the Māori male body that was to become the urban nightmare as imagined through the hyper-violent “Jake the Muss”’ (Hokowhitu 53).

Jensen skewers a slightly different slew to the male Pākehā colonist-colonised relationship, with especial attention to New Zealand literature. For him, the mid-twentieth century muscular masculinist movement was a deliberate response to ‘previous New Zealand literature as precious, flowery, sentimental, socially naïve and out of date. [The authors] were attuned to the new modernist and social realist developments in English and American literature’ (42).

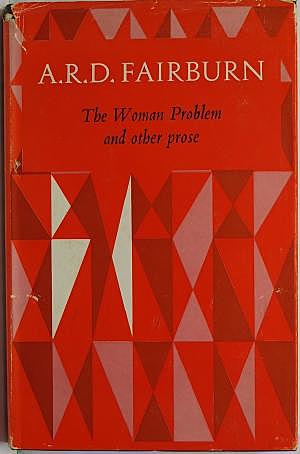

These writers had a desire to establish a rigid, independent and genuinely sui generis New Zealand literary profile, based on strict macho tropes, such as, ‘work, sport, drinking and war, through a robust physique and fatherhood; as trying to be stoical and laconic; as shrinking from expression of feelings, distrusting articulacy and education’ (Jensen 40). Through media such as Glover’s Caxton Press and the new Tomorrow magazine, and covering sturdy male topics and writing in patented hardboiled and terse masculine patterns, they strove to, ‘develop a distinctive national literature’ (Jensen 45) via this ‘masculine mythology.’

Author Patrick Evans, by the way, has the grace to admit that Jensen, ‘quotes with disapproval my comment…that such writers as Sargeson and company were a fragment of the monolithic society they came from. For Jensen, these writers wrote to interrogate their own position’ (226). In other words, Jensen travels beyond ‘simplistic’ male reactions to their settler roles as ‘merely’ rugged farmers and labourers striving in a physically tough natural environment: – his crew of writers were on a mission to erect a bigger edifice that incorporated both this physicality and an ability to write as incorporating a masculine style, or as Evans puts it, with a ‘a no-nonsense tone and…a hardboiled register’ (226).

Necessarily, women had no place for – let alone in this crew. Fairburn, for example, penned a long essay entitled, The Women Problem, while Gaskell, complained, ‘“Bloody women,” he muttered, “Bloody women,”’ at the end of his 1978 short story The Fire of Life (68).

Thus, ‘An emerging, confident, authentic voice proclaimed a new dawn of literary nationalism. Swept aside were the laments of deracinated colonisers, the prurient sentimentality of late-Victorian imitators, and the insipid gestures towards an indigenous English language literature of Georgian poetasters,’ as critic Paul Millar wrote when reviewing Stuart Murray’s Never a Soul at Home, New Zealand’s literary nationalism and the 1930s (79).

This is a book Jensen owes a considerable amount of insight to, even if the text is never referred to in his own work. Millar wants to say that this generalized and rosy overview of a new literary nationalism was more of a gloss from later literati and that – at the time – contemporaneous writers like Robin Hyde saw such men as literary gang members as revealed in her article, Singers of Loneliness. The appalling irony is, of course, that the gangsters at the time repudiated women writers such as Hyde herself, Ursula Bethell and Eileen Duggan, and it has taken decades for them to receive their deserved attention and accolade as (women) writers (see for example Michele Leggott et al and their NZEPC online resource pertaining to Hyde).

Academic Matthew Bannister, meanwhile, even more cogently explained these mid-20th century New Zealand Pākehā male writers’ masculine topics, stylizations, camaraderie and inherent sexism: all were a result of an inferiority complex in regards to the British colonial regime and that, in fact, such authors were not as free as they thought. Rather they were in many ways dupes of their London-centred liege. What Bannister describes as ‘a strong, masculine ideal functioning within a patrilineal tradition fought against foreign “femininity”’ was actually an echo of the wider ‘global context,’ whereby, ‘writers felt obliged to emulate the dominant culture, by stressing non-literary accomplishment, attempting to normalize writing as an activity by proving writers’ solidarity with ‘ordinary blokes.’ A la Jensen’s own, earlier summary of these male authors as attempting to show themselves as ‘real’ Kiwi blokes in both word and deed, but with an extra layer.

So, for Bannister, ‘the Kiwi bloke was also produced within an international context.' He quotes from a seminal text by Bill Ashcroft et al, whereby colonized males, ‘are frequently constructed within a discourse of difference and inferiority by the colonizing power and so suffer discrimination themselves…at the same time they act as the agents of that power…they are both colonized and colonizer’ (211-212). Which means, essentially, that white male New Zealand writers of the mid-twentieth century, in seeking to establish a rigidly-defined nationalistic literary edifice, were not only reproducing discourses of domination – of women and Māori and their respective alternative narratives – but also of their own subordination, namely, ‘as working class manpower fulfilling the economic needs of colonizing powers’ (Bannister). Bannister, then, travels well beyond earlier scribes such as Phillips.

White male New Zealand writers of the mid-twentieth century, in seeking to establish a rigidly-defined nationalistic literary edifice, were not only reproducing discourses of domination – of women and Māori and their respective alternative narratives – but also of their own subordination.

All of the above, then, is well and good, and palpably probable, especially as regards a firm majority of New Zealand males of whatever ethnicity, historically kowtowing during our colonial and neo-colonial epochs to imposed and then self-inculcating British manipulations, extending well beyond literary genre.

I want here to make it clear here, that despite my almost incessant quoting of male writers rationalizing being male in New Zealand as above, I am not orchestrating some sort of subliminal complicit masculinist/sexist pantheon to somehow ‘rationalise’ their sexist, all-too-often misyogynist tendencies. Far from it – there is no excuse for patriarchy then or now, regardless of these historical factors and forces.

Indeed an early quote from Jock Phillips best summarises my own approach here: ‘Only by understanding the values and the attractions of male culture in the twentieth century can we understand…[how] males have treated New Zealand women. It is time to study the oppressor as well as the oppressed’ ((b) 218).

Nowadays?

Which leads on to the vital enquiry. Surely all this masculine literary hegemony is recent history – in 2017, and women do have a fair share of the page nowadays, both as represented and representative writers, publishers, critics, literary festival participants – and – as represented more centrally in a wide gamut of fictive and indeed non-fictive topoi. Surely?

But it isn’t and they aren’t. As Bannister quite clearly points out in 2005:

many commentators, writing in the 80s, believed that the colonial legacy and its accompanying cultural baggage were increasingly irrelevant and looked forward to newer, more multicultural and diverse representations of identity. So why then does the Kiwi bloke still exist?

The original white elitist masculinities, as initiated in Britain, unfortunately continue to implode our everyday lives even now, as so-called globalization continues to bite. Sociologist Raewyn Connell, an important harbinger when it comes to writing about categories of masculinity and their implicit sexism, stresses also that:

Specific masculinities, specific gender relations, were inscribed in colonialism and imperial expansion themselves…Gender was embedded, was formative, in imperialism, and thus in the initial construction of global arena (12-13).

Bannister extends on how, ‘imperial structures of power are now re-articulated and further developed through global capitalism,’ while Connell, herself, more latterly, also sees the current agents of neo-liberal globalization as enforcers of white – and indeed Māori – masculinities, which I will refer to further on.

New Zealand literature is then, also still replete and complete with sexist bores and patriarchal prattlers; something that re-hit me recently when I read and reviewed two contemporary books by Kiwi males and which became the genesis of this piece. One is a novel, which won accolades and a swamp of prize-money (think Ockhams), the other a collected poetry work, as published by a mainstream university press in this skinny country. What pissed me off beyond the overt masculine tropes marrowed throughout both books, was the myopic critical effusion accorded both, with complete blind spots as to just how sexist both books intrinsically are.

New Zealand literature is...still replete and complete with sexist bores and patriarchal prattlers.

For Coming Rain (2015) by Stephen Daisley and Blood Ties (2017) by Jeffrey Paparoa Holman are sexist tracts, sublimating women not so much via overt sniggers and disparagement, nor the patronizing – sometimes savage and downright nasty – dismissal of women by the masculine writers identified by Jensen et al, but by their sheer omission. Sexism by preclusion, if you will, but sexism nevertheless. Jones succinctly summarised such sexism when he describes Curnow: ‘his work generally does not so much denigrate women as insistently foreground predominantly masculine concerns’ (427).

Both books are exercises in what Connell – yes, a woman writer as opposed to all the mainly manly jokers I adumbrated above (alarmingly, Bannister had blindly surmised Connell was a male) – would once have nominated as complicit masculinity. Not hegemonic masculinity as such, but a vast tract of mankind imbued with patriarchal whiteness, violence, suppression of emotions and an obsession with physical strength.

Suffice to say, both Daisley and Holman have found no little accolade and literary success by ‘virtue’ of being New Zealand sexist male authors. Let me quote myself reasonably faithfully at some length, from my own recent reviews of their respective works, given that Holman’s poem, which I will now undress in full, was published in 1998.

Holman is in fact a throwback to Fairburn, Glover and Co. Ltd: his work is manifestly sexist by omission and yet is relatively extolled in 2017. The following poem from Blood Ties, for example, relegates the sullied woman to the level of flapping linen on a West Coast clothesline.

t-bar clothesline, Okarito

a t-bar bearing

the lichen of centuries: his bush socks

soaked last night

in beer-sweat

buried in his boots

in the pub.

her wet panties

pissed in fright

when the back door

locked to keep him

out for the night

caves in, and

O, Christ!

something she can’t

scrub out is in her.

Teatowels flap naval

signals, double-bed sheets

spinnaker belly: tacking the rusty

centre bolt shrieks. Bellbirds

toll the flax, herons stalk

the creek, eels grow tusks

in the black lagoon

and it’s marvelous drying weather.

To quote my own review:

Over and above all else, the resonant presence in this book is of good keen men, and the Crumpean reference is deliberate. This is a particularly male-oriented selection of poems and themes.

I continue:

Several poems are dedicated – to men. Man worship is a term I would utilise here, for women – other than the poet’s brave mother and one empathetic snippet regarding Michele Leggott in it will sound – are scarcely visible anywhere at all, except where they are the victims of bashings from drunkard spouses, as in the rather worrying poem above, whereby the clothes line outside seems to engender more empathy than the battered wife.

On Daisley I will quote excerpts from my Landfall 232 review of his award-winning Coming Rain:

I also get flashbacks to Barry Crump and good-keen-manism: this is a brutal, violent story, yet with patches of tenderness…But such softness is generally subsumed beneath a steady macho drumbeat, where men make do as best they can in a godless environment under a steady coruscating sun – until the rains come.

Then there’s his sprightly but too lightly traced daughter, Clara, the only female character with any sort of star rating, in a book which goes beyond downplaying womenfolk further into a distinctly anti-female gambit, most especially via the copious misogynistic ramblings of Painter…one gets the distinct impression he blames the fairer sex, in fact the sexual act in general, as the root cause of entropy and evil, as the schism-maker between men [with]…‘“Never trust a woman son, they’ll break your heart.”…“You ever seen a woman having a baby?...Fucking mess. All over the bloody bed and floor, shit everywhere. Like an animal they are”’ (166-170).

It is obvious – Coming Rain, as with Blood Ties, made me exasperated, not because Patricia Grace didn’t win – well partially, actually. No, because both books are so bloody sexist and it is 2017! And my exasperation is compounded, when I recall what Eleanor Catton stated recently about New Zealand male authors and reviewers, given that I reviewed her most recent novel and didn’t elite it – and I am male. She stated straight up front to The Guardian:

“I have observed that male writers tend to get asked what they think and women what they feel," she says. "In my experience, and that of a lot of other women writers, all of the questions coming at them from interviewers tend to be about how lucky they are to be where they are – about luck and identity and how the idea struck them. The interviews much more seldom engage with the woman as a serious thinker, a philosopher, as a person with preoccupations that are going to sustain them for their lifetime." [italics mine]

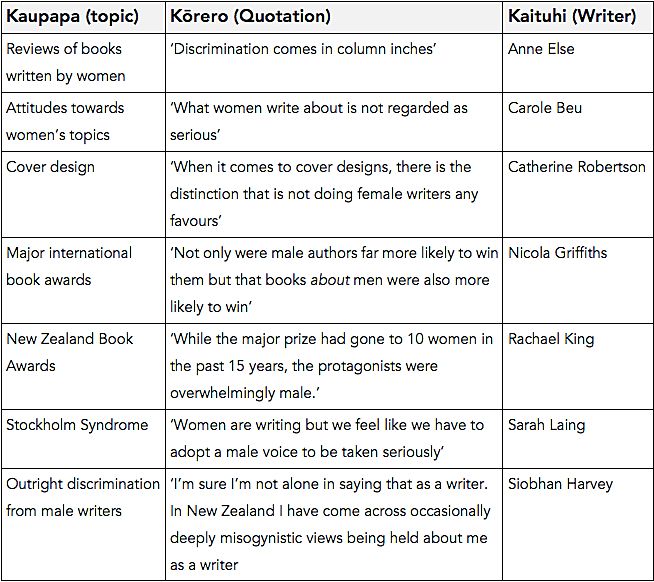

A particularly revealing exegesis of valid concerns by women writers regarding the concretized and ongoing patriarchal literary environment in this country was delineated on Stuff.co.nz in 2015, under the title, ‘Does women’s fiction get the respect it deserves?’ As summarized by me here:

Then even more recently I read poet Paula Green’s grim gripe about an obvious gender preference at the 2017 Auckland Writer’s Festival, whereby Hera Lindsay Bird was shunned under waves of man-love and boyish back-slapping hero-worship. With Paula’s permission, I quote extensively from her May, 2017 NZ Poetry Shelf post:

The Old Guard and the New Guard session featured Hera Lindsay Bird and Bill Manhire in conversation with chair, Andrew Johnston…I wrote a swag of notes based on Bill's conversation and readings and scarcely anything on Hera because for some inexplicable reason she was sidelined on stage. She got to talk about the fizzing international reaction to a couple of her provocative poems and to read one of them (after saying these poems were her least favourites in the book). Bill was invited to read several. Hera did not get a chance to read another poem (until I invited her to do so in question time) or to talk about the way her book offers so much more to the reader… It felt like Hera had 20% of talk time but maybe that was not quite accurate. There was scant if not zero engagement with what her poetry is doing beyond the shock factor…The session felt like a step back in time where if a woman speaks it is claimed she is dominating… I don't know why this happened but in my view there is no excuse because it appeared to be downright sexist.

Green’s words made me reflect on what I wrote some years ago, regarding nga mōteatea Māori and the mightily manifest role that Māori women had in both their genesis and performance. As here:

Māori women had historically a major role in not only the composition of Māori poetry, but also its performance: they composed as they were the most affected by battle loss and the subsequent anxious awaiting the return of the man, love loss and the desertion of the man, (death and betrayal), curses and insults from other women. Tuini Ngawai (Ngāti Porou) was just one such important modern writer of ngā mōteatea Māori, and a collection of her work was produced in 1985…the composers of ngā mōteatea Maori were generally high-born women or (male) chiefs, who advanced the social values of high birth, chieftainship, primogeniture via their compositions. (Rapatahana (c))

I must pause to ask, what the hell has happened ki te ao Māori [to the Māori world]? Then I pore/paw over recent statistics that show ngā wāhine Māori are the people most subject to domestic violence in this dominion, are still beset by tāne with Jake Heke complexes and Pasifika women were also, ‘more likely to be victims’ (Stuff.co.nz 2014).

I must pause to ask, what the hell has happened ki te ao Māori [to the Māori world]?

There are no excuses for this regardless of these males’ pervasive disestablishment as an indigenous population, whereby their land, language, religion, mana, socio-economic status, existential being remain stolen and which all too many still struggle to attain – to the extent that Māori male youth have one of the highest teen suicide rates in the so-called developed world, as any sense of intrinsic identity never flourished within them.

So then, I have to concur that something still stinks very bad in Aotearoa. This excerpt from Apirana Taylor’s despairing and desperate poem ‘Sad joke on a marae’ remains a nursery rhyme for all too many iwi:

Then I spoke

My name is Tu the freezing worker

Ngāti D.B. is my tribe

The pub is my marae

My fist is my taiaha

Jail is my home

Significantly, Hokowhitu iterates that Māori men were not always so cast. He states: 'The most striking image of Māori men I have seen is a late-eighteenth or early-ninetenth-century photograph of a group of tāne and children outside a whare (house). Some of the tāne have their arms around each other, while others cuddle their children…this photo suggests that tāne stem from a loving and caring culture (276).'

It's a point that Daryl Gregory, CEO of He Waka Tupu, further stresses:

The process of colonization was violent and left Māori feeling subservient to the colonizer. Seeing themselves as warriors made them feel strong, when in fact traditional Māori men worked in a range of fields, such as gardeners and midwives…The image of a Kiwi bloke hiding his feelings was a colonial idea that did not fit in with traditional Māori culture where men had regular chances to speak at hui and social occasions. When you take those elements away and dismantle or replace them with something else, that’s where the problems for Māori men are.

And yes, of course many New Zealand males per se are also victims of masculine constructs, but because of what they are pummeled with in all too many cases from birth, namely, ‘be tough, be strong, play hard,’ they won’t say so, eh. How genuinely tragic for all, then, that Aotearoa New Zealand has remained so sexist, both literarily and literally.

A generalized continuum of oppression and suppression could be ‘white Anglo-American males’ (an elite clique) to ‘other white males’ to ‘other males’ to ‘white women’ and finally ‘other women’. I want to reiterate that no manipulation of masculinities excuses violence or patriarchal attitudes and barriers anywhere, at anytime. Nor do the historical and contemporary processes I’ve outlined excuse the peripheralisation of women on the page. All are chapters in the same sexist tome.

I want to reiterate that no manipulation of masculinities excuses violence or patriarchal attitudes and barriers anywhere, at anytime.

This country, despite its John Keysian dollar bill self-congratulations, is seriously amiss, when it comes to a fair and level playing field for all women. New Zealand also rates right up there among OECD countries, as having the worst domestic violence rate for women of whatever ethnicity, with the NZ Herald stating ‘80% of incidents going unreported.’

More women may be being heard and published, but far too many are being hurt and punished – by men. It must stop. Fuck rugby racing and beer as some sort of panacea; it’s way beyond time to move on. As author and sexual assault researcher Jan Jordan wrote this year:

The most fundamental element of patriarchy, enduring through the centuries, has been the premise of men’s ‘natural’ superiority over women…we need to recognize how deeply embedded the patriarchal legacy remains within our culture.

What to do?

One logical avenue is further space, status and potency being given to and grabbed by women writers. In so enabling women authors across all literary genre, the masculine hegemonies can alter, for hegemonies are not set in concrete – they do and should change. Indeed women have a major role in so doing. Let’s turn to the erudite words of Connell, in 2017, once more: 'There is abundant evidence that masculinities are multiple, with inherent complexities and even contradictions; also that masculinities change in history and that women have a considerable role in making them, in interaction with boys and men.'

An example of such is the recent trend of New Zealand literary festivals supporting feminism. As writer Elizabeth Heritage notes in her 2016 essay, ‘The F Word: Feminism in NZ literary festivals’:

Keen literary festival-goers in the country will have noticed that, this year in particular, we’ve had…many events that feature prominent feminist thinkers and writers, and/or involve explicit discussion of feminism…Why is this? Partly it’s to do with who’s running the festivals. Rachael King, Literary Director of WORD Christchurch says: “I think it’s the nature of who is programming the festivals: usually intelligent women.”

In this selfsame article, the names of Nicola Strawbridge, Co-Programme Director at Going West Books & Writers Festival; Anne O’Brien, Director of the Auckland Writers Festival; Anna Jackson, one of the organizers of the Ruapehu Writers Festival, and Kathryn Carmody, the programmer of the NZ Festival Writers Week in 2014 and 2015 are all mentioned as supporters of a far more women-orientated literary regime in this country, one that, while not sidelining male authors, necessarily abrades the patriarchal structures of earlier such events.

Men too can upturn historical trends. Connell clarifies:

Hegemony is a historically mobile relationship among social groups. It is possible to challenge for hegemony….The goal is not to abolish masculinity…but to create a hegemony for forms of masculinity that already exist in the lives of men, masculinities that are peace-making not war-making and that flourish in a context of gender equality…change in gender relations involve not only personal relations, identities and intimate life, but also large-scale institutions and the structural conditions of social life…corporations, states, and transnational structures of communication, trade and military power (2012 14-15).

I think it also particularly pertinent to return to Hokowhitu’s wise words, for even marginalized male groupings do have agency and can overturn the prevailing hegemonic qua white masculinity still pervading Aotearoa: 'Colonized indigenous ressentiment must be replaced by an indigenous mindset that takes ‘responsibility’ for colonization, not in order to replace the colonizer from responsibility, but designed to re-claim the freedom to choose beyond a colonized/colonizer mentality ((b) 55).'

The same applies to subordinated masculinities – that is men who display opposite tendencies to other masculine groupings, such as a supposed physical ‘weakness’ as well as their emotions, like gentleness and sadness, and sexual preference. They too have an increasing agency.

Several male New Zealand poets are in fact writing reflective and considered poems regarding a different form of masculinity.

Several male New Zealand poets are in fact writing reflective and considered poems regarding a different form of masculinity, one that incorporates sensitivity, empathy and yet retains strength. Poets such as Chris Tse who writes about being gay, and Vaughan Gunson, in his parental pieces such as ‘the chase,’ ‘portrait of the artist as a parent of young children’ and ‘the answer to first questions’ are at the vanguard of a different male voice in New Zealand letters. Poet Bill Nelson’s debut collection Memorandum of Understanding was referred to by poet Kate Camp in her launch speech as:

…manly. I guess what I mean is that its subject matter covers a lot of traditional male territory: one day cricket, John Coltrane, big screen televisions, “I first touched your breast / accidentally”, “How to change the oil in a 1979 Ford Escort”... But these masculine tropes always appear in new guises, in a new tone. If I was an academic I’d be talking about contemporary masculinities.

As is Tim Jones and his aptly titled collection Men Briefly Explained. Here is the titular poem, an honest and refreshing depiction of what New Zealand men essentially are:

My friend and I are talking to

the most attractive woman in the room.

My friend and I are talking to

the most attractive woman in the room.

We’re talking big: theories, hypotheses,

each wilder than the rest.

How huge our brains must be!

How fit our genes, to allow

such brilliant and superfluous display!

The most attractive woman in the room

smiles at us each in turn.

She is clearly impressed, and her sisters

are smiling too. We are gibbons

swinging through the trees. Chimps

waving sticks and bones. Gorillas

in the mountain forests,

beating hairy chests

as the poacher Time takes aim

With such gentle self-mockery men can overturn themselves. Women have been trying to do so for decades.

So, even more posthumous accolades should be accorded poet JC Sturm, who summed up the weight of sheer oppressive white manpower weighing heavily on all women in Aotearoa, albeit this excerpt of ‘Māori to Pākehā’ which appeared in Landfall is ironically ‘all about’ her husband, James K. Baxter:

You there

I mean you

Beak-nosed hairy limbed narrow-footed

Pakeha you

Milton directing your head

Donne pumping your heart

You singing

Some old English folksong

Meanwhile trampling Persia

Or is it India, underfoot

With such care less feet

Kia ora hoki ki Hinewirangi mō te hautoa o enei kupu [Thank you also to Hinewirangi for the courage of these words from Screaming Moko (28-29)]:

Historians

You come white historians

with your expertise on me

– I spit on you out

of my mouth,

my mind

Maru-iwi

Moriori bastardization,

Whakapapa speaks of

Whatonga, Toi, Kupe

– Maru iwi – Maori

a oneness.

White historians,

we

opened our marae to you,

never seeing

hidden agendas

degrees,

doctorates.

You

sit in your whare wananga

telling me about the history

of my people.

I shame:

Elsdon Best

tells me

I am a savage, a barbarian.

R.D. Long

considers me

a dirty savage.

The very Reverend James Buller says

I am a devil worshipper.

You, white historian,

the expert on me?

Kia ora ki Paula Green hoki [Thank you also Paula Green] whose further right-on-the-nose missive from her poetry postings, must be quoted right here:

I do not know why the sideline happened, and I do not think it was deliberate, but I am drawing attention to it because it seemed like a replay of the Old Guard of New Zealand poetry where men ruled the poetry roost and women's voices were sidelined, and even worse, denigrated, devalued and not given prominent visibility in the fledgling canon. And that felt like such an irony... I have experienced several examples of being sidelined by a male poet in a public forum but I was not and am still not prepared to hang out personal anecdotes. However I am prepared to challenge or highlight ways in which women are disadvantaged by men in our literary landscapes.

And yes, all hail Hera Lindsay Bird. I will not shy away from stating that I don’t think all her poems are great – and that my being male has zilch to do with this viewpoint. But I will stress that the voices of Hyde, Sturm, Hinewirangi, Green, Catton, ngā wāhine Māori rāua ko Pasifika, and Bird at her best, are vital visceral vessels to speed up the emasculation of our overly and overtly male corpus.

In so doing their words, their stories, will continue to deconstruct the massive masculine mansion sublimating to the basement, all too many in this confused country. In so doing also, they will eventually even up everything for everybody else who cannot – and never could – squeeze into the white, middle-class male mould. Thus previously subordinated writers of whatever gender, of whatever ethnicity, in whatever language – because, as I hop onto another Rapatahana hobbyhorse, English has all too often been the lingo of the kingmakers.

I will finish with what I reckon are the best two lines of (fuck-you man) poetry I’ve read for years, maybe ever. From ‘KEATS IS DEAD SO FUCK ME FROM BEHIND,’ says it all:

Eat my pussy from behind

Bill Manhire’s not getting any younger