The Past Matters: Reflections on Tangata Whenua

Hautahi Kingi reflects on last year's mammoth illustrated Maori history

While Genghis Khan marauded the Asian steppe and the Crusades blazed through the holy lands, Aotearoa lay undiscovered at the bottom of the world. Cambridge University, which would publish the first official Māori dictionary in 1820, opened its doors before any knowledge of New Zealand’s existence. While human history unfolded in all its wonders and tragedies, Aotearoa patiently awaited the arrival of its first land mammals.

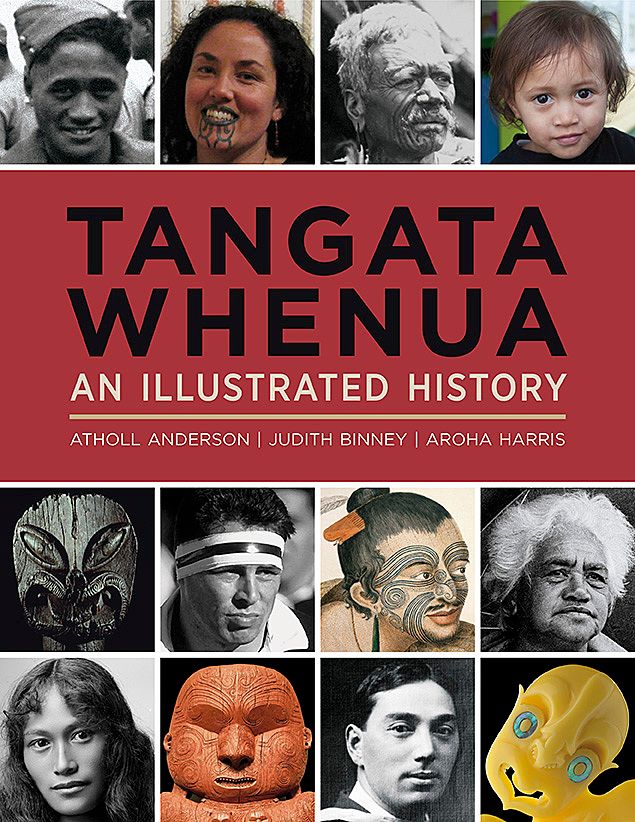

Tangata Whenua begins by declaring that “the first human inhabitants of New Zealand ... arrived about 800 years ago.” We are then expertly guided through the events that would ultimately shape modern Māori and New Zealand society. Tangata Whenua is divided chronologically into three parts, each masterfully crafted by a respected academic of that period. Atholl Anderson, Judith Binney and Aroha Harris construct a comprehensive history of Māori over 489 beautifully illustrated pages. It is a large book, but its weight extends far beyond its physical size. Tangata Whenua is at once a compendium of facts, a treasure trove of images and a superb narrative, equally at home on the coffee table or in the reference library.

As we follow the 60,000-year migration of Māori ancestors from the coasts of China, down into the margins of Southeast Asia and across the Pacific, we immediately recognise that this is a serious book. Tangata Whenua is as staggering in its detail as it is in appearance - a big book with a bigger story.

In the first chapter alone, scores of linguistic, genetic, bacterial and archaeological evidence are offered to explain the dispersal of Māori ancestors across Polynesia. In Te Ao Tawhito (“The Old World”), the first of Tangata Whenua’s three parts, Atholl Anderson escorts us through the complex history of genetic intermingling that lead to the emergence of the Lapita people around 1300BC. The Lapita people, the first inhabitants of the South Pacific, would go on to settle the islands of West Polynesia. In places like Samoa and Tonga, a distinct Polynesian culture would develop - “the place of a ‘becoming’ rather than a ‘coming’ of the Polynesians.”[i] These Polynesians would then sail east to settle in the Cook and Society Islands in the first millennium AD. It was from here, in the eastern Pacific, that the eventual settlers of New Zealand would come. We may now be Tangata Whenua, but Māori are descendants of Tangata Moana, oceanic wanderers on the emptiest corner of our planet.

The motivation of these wanderers remains open to speculation. Māori legends refer to mass emigration forced by population growth and warfare. Modern evidence suggests the cause may have been a large volcanic eruption in Indonesia in AD1257 that instigated a period of global cooling. Perhaps it was just mere curiosity. Maybe Herman Melville unwittingly spoke for Māori when he wrote, “I am tormented with an everlasting itch for things remote. I love to sail forbidden seas.”[ii] While those seas may now be less forbidding, the itch evidently remains. With around one million New Zealanders currently living overseas, it is an itch that connects our generation with the first.

For much of Te Ao Tawhito, we are restricted to the findings of archaeology and oral tradition. Because Māori did not keep written records, our knowledge of prehistoric Tangata Whenua is limited to “shadows conjured up around material remains.”[iii] It is not until the personal accounts of Abel Tasman in 1642 and James Cook in 1769 that we take our first glimpse of individuals as “emotionally expressive, ritually constrained, acting social and reacting politically.”[iv] Crass even in compliment, early descriptions of Māori bear the familiar whiff of patronizing self-importance.

The Natives of this country are a strong raw boned well made Active people. Many of the women ... had very good features, and not the savage countenance one might expect.[v]

Over the centuries, Māori had lost any notion of the existence of other people, so the arrival of Pakehā was both frightening and exhilarating. As early outbreaks of violence dissipated, European visits gradually extended into periods of co-residency.

Part two, Te Ao Hou (The New World), is devoted to the 100 year period from 1820 to 1920. Central to these chapters is the fundamental tension in Pakehā and Māori relations - the conflicting concepts of landownership. The core of the disagreement was that Māori did not traditionally “own” land in the European sense but rather held rights to its use. From the European point of view, the Māori framework directly contradicted the underlying foundations of capitalism on which European society was based. Without property rights, basic concepts of buying and selling were rendered meaningless. The European notion was equally at odds with Māori understanding. Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au - I am the river, and the river is me. Whanganui iwi view the river as an extension of themselves. How could Tangata Whenua be expected to give up the very whenua from which their identity was derived?

Thankfully, Tangata Whenua does not fall into the “good Māori, bad Pakehā” trap. Many instances are sympathetic to Pakehā beliefs and integration. In discussing his support for the Treaty at its negotiations, Tāmati Wāka Nene of Ngāti Hao asks:

What did we do before the Pakehā came? We fought, we fought continually. But now we can plant our grounds, and the Pakehā will bring plenty of trade to our shores. Then let us keep him here. Let us all be friends together. I am walking beside the Pakehā. I’ll sign the pukapuka.[vi]

Nevertheless, the exploitation of Māori was often shocking, and the authors pull no punches in assessing its long term impacts. By 1864, the Crown had acquired 34.5 million acres of land from Ngāi Tahu at a cost of much less than a penny an acre. The ‘Kemp Purchase’ of 1848 transferred one third of New Zealand to the government land commissioner in a single transaction.[vii] “It led directly to the creation of an almost landless proletariat which still broods over the manner of their dispossession.”[viii] Māori were left with less land than was required for subsistence, effectively enforcing a form of state dependence and a socioeconomic structure that persists today. The Ngāti Mahuta chief Tamati Ngapora indicated that the consequences were not lost on the people of the time either:

If the blood of our people only had been spilled, and the land remained, then this trouble would have been over long ago.[ix]

The period covered by Judith Binney in Te Ao Hou is perhaps the most-studied time in New Zealand history. Much of the material is heavily explored by previous work. Buried within the familiar events, however, are some lesser-known gems. For example, while many European ideas were eagerly adopted by early nineteenth century Māori, religion was not one of them. Visitors were puzzled by the absence of religious structures and the secrecy of religious observance. In his journal, James Cook wrote, “With respect to religion, I believe these people trouble themselves very little about it.” [x]

Another complained that “the attributes of the Atua are so vague, and his power and protection so undefined, that no religious system could be perceived.”[xi] Early missionaries made little headway, as Māori criticism of Christianity started early. Against the missionary belief of an all-encompassing god, Māori argued that if this were so, he would have acted impartially by giving kumara to Europeans and horses to Māori. In 1819, Samuel Marsden wrote:

Many other arguments they used to prove that there must be more than one God. Their reasoning faculties are strong and clear and their comprehension quick.[xii]

Māori provide one of the few historical instances in which indigenous people instead exploited missionaries. While being used for their agricultural, carpentry and blacksmithing skills, missionaries were forced to remain in one settlement, preventing them from reaching out to proselytize. It would be ten years before missionaries could claim a single convert.

Early Māori resistance to western religion is just one illustration of a major theme that Tangata Whenua shares with Michael King’s “The Penguin History of New Zealand.” Many examples succeed in “depicting ... Maori as adaptive and increasingly influential survivors, rather than perpetual victims.”[xiii] Throughout the book, Māori display a remarkable ability to adapt to the changing political and social landscape. Despite many disappointments, Māori spent decades lobbying through official channels, showing great stamina and patience within a foreign framework run by an often unsympathetic bureaucracy.

Te Ao Hou ends with World War One. Just three decades after Te Kooti thrust the barrel of his gun into the ground, announcing there would be no more war in New Zealand, Māori were asked to leave home to participate in another. Less than a generation after fighting the Crown for their own survival, 2,277 Maori men would fight, and 366 would die on its behalf.[xiv]

In Te Ao Hurihuri (The Changing World), the third and final part of the book, Aroha Harris describes the emergence of modern Māori culture. The post-war period saw Māori embark on another great migration – this time to the cities. The share of Māori living in urban areas increased from 11.2 percent in 1936 to 62 percent by 1962, and continued to increase through to the 1990s.

Simultaneously, one of the most influential economic models of the 20th century - the Harris-Todaro model - was developed to explain the rural to urban migration during the same time in tropical Africa. To my knowledge, the model was never applied to the Māori movement to urban areas, but its employment predictions are uncannily similar. Māori families moved for opportunity and work – yet in 1981, the Māori unemployment rate was 14.1 percent compared to 3.7 percent for the non-Maori workforce.[xv]

Nevertheless, armed with youth and enthusiasm, many Māori would flourish in the new urban setting. Chapter 13, entitled “Rights and Revitalisation,” documents the resurgence of Māori culture into its distinctly modern guise which we recognize today. Māori expressed themselves through sport, art, academia and politics. From Billy T. James and Kiri Te Kanawa to Buck Shelford and Dame Whina Cooper, the national profile of Māori achievement could no longer be ignored. Through novels, film, poetry and art, Māori simultaneously expressed their grievances with Crown treatment, while also defining their own unique voice. Tangata Whenua singles out the work of poet Hone Tuwhare as particularly important. In ‘Hotere,’ Tuwhare explores the complexity of an abstract painting while revealing his typically Māori friendship with its artist.

When you offer only three

vertical lines precisely drawn

and set into a dark pool of lacquer

it is a visual kind of starvation

and even though my eyeballs

roll up and over to peer inside

myself, when I reach the beginning

of your eternity I say instead: hell

lets have another feed of mussels

Art and people are brought to life through hundreds of images, which both complement the material while also providing a refreshing contrast to the often heavy narrative. The design of Tangata Whenua is central to its appeal. No two consecutive pages are without illustrations. Photographs of flaxwork are set alongside early sketches of Māori communities. The deep green of pounamu contrasts with the black and white photographs of Māori land war prisoners. The portraits and group shots provide a welcome human element, which can often be lost in a historical sea of cause and effect. The smiles and frowns on scarred faces, the anachronistic blending of traditional korowai with three-piece suits, and the tears of mothers sending sons to war allow us a glimpse into the emotions and feelings of individuals as people.

The recounting of everyday human interactions serves a similar purpose. In doing so, Tangata Whenua introduces a host of characters along the way. Some are familiar - the likes of Hone Heke, Titokowaru and Sir Apirana Ngata - and some less so, such as Te Taonui, chief of Te Popoto in Hokianga, who was known for his ability to assess the dimensions of a wooden spar at a glance.[xvi] We learn about an occasion when an early European settler failed to produce a toki (an axe) to purchase a pig. As he walked away in disappointment, the Maori vendor called out to him, in the pidgin Māori of the day, “No tokee tokee, no porkee porkee” laughing heartily at his own wit.[xvii] With the benefit of hindsight, it is tempting to invest historical figures with heightened responsibility and significance. In these moments, we see ordinary people living out their lives, trying to make the most of their rapidly changing worlds.

By the turn of the century, Maori could finally look forward optimistically “in a way undreamed of a century ago.”[xviii] Educational institutions such as kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa had already produced its first generation of rangatahi, of which I am a member. Other initiatives such as Māori tertiary scholarships and on-campus whanau like Te Rōpū Āwhina at Victoria University continue to contribute to the large improvement in Maori educational achievement.

Tangata Whenua ends by summarizing the past and convincing us of its importance for the future. Entitled “The Past Matters,” it is an elegant conclusion with stunning prose that offers an optimistic but cautious outlook:

Tangata Whenua is not a simple history of Māori progress. Some things have changed, and some have stayed the same. Māori cope, survive and excel in this volatile world - but need now, as much as ever, that old sense of communal strength, whanaungatanga, and its principles of mana and rangatira. The past, as ever, speaks, recalling the deeds and drive of tupuna to the concerns of the present, and guiding the future.[xix]

Humanity took a long time to reach our distant corner of the world. Tangata Whenua, at long last, tells the complete history of those who made it first. In doing so, it also tells the story of those who would come to live alongside Māori. Tangata Whenua fosters a mutual understanding and respect that allows all New Zealanders to celebrate and appreciate our differences rather than shy away from them.

For this, and many other reasons, I am grateful for this book. We all should be.

Hautahi Kingi

Ithaca, NY

Hautahi is a fourth year Ph.D student in the Department of Economics at Cornell University.The Auckland Writers Festival is holding a free session with Tangata Whenua authors Atholl Anderson and Aroha Harris on the afternoon of Saturday 16 May. More information is available here.