Casting a Light on Women’s Shadow Labour: A Review of Past Caring? Women, Work and Emotion

Sarah Jane Barnett reviews Past Caring? Women Work and Emotion, a selected history of women’s care work in Aotearoa

The pun of the title says it all: with our tiring history of care work, are women past caring? The very existence of this new history, with all-women contributors, tells us the answer is obviously no.

Much care has gone into Past Caring? Women, Work and Emotion, a selected history of women’s care work in Aotearoa, edited by Barbara Brookes (whose A History of New Zealand Women won an Ockham in 2017), Jane McCabe and Angela Wanhalla. The result is a quietly subversive book, revealing the essential ‘shadow labour’ on which Aotearoa society was built, and raising questions about the justice and morality of care, both paid and unpaid, that often falls to women.

There is a cornucopia of care in this book: a Māori grandmother’s story of caring for her whānau; the Pākehā notion of reciprocity of care; the transition of traditional night-time ayah care work from Northeast India to Aotearoa; care given by women through food preparation and the creation of clothing; a Rarotongan leader’s care through duty to her people; unwed mothers pressing American servicemen to care for their children; and the sense of service that gave a long-term social worker her drive. The book also explores the way we portray women’s care work, from the ‘mother alone’ figure in Aotearoa cinema, to the way care has been documented by women, such as ‘missionary wife’ Helen Smaill’s photograph album of being a “mother, nurse, cook, seamstress, laundress, hostess and teacher” in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu).

So why should we care about these stories? Because to change systems of inequality in Aotearoa we need to not only understand our own experience, but the experiences of others, and how they interact. The intersectional subtext being: gender matters when it comes to the issue of care, but so do ethnicity, socioeconomic status and geography, and they layer upon each other like a discrimination gateau. As McCabe declares, “All caring occurs at the endpoint of a genealogy of care, moving through families and cultures, and across shifting social contexts. In colonial settings, these shifts have often been abrupt, forced, and institutionalised.”

The decentralising of Western perspectives is without a doubt a strength of this book.

The decentralising of Western perspectives is without a doubt a strength of this book. A brilliant example is Melissa Matutina Williams’ chapter about how her grandmother Tina, or ‘Nan’, cared for their extended whānau, who in turn cared for Tina as she aged. Williams says, “Nan’s care of others (and, in turn our care for her) shaped our relationships to each other as a whānau, and our connection to our papakāinga (our whānau home and whenua/land).” Williams uses Nan’s story to show that, as Aotearoa became urbanised, the model of care in her whānau was not supported by social and welfare systems based on Pākehā values. Heartbreakingly, she writes of this time:

Severing connections between tamariki and their whānau was further facilitated in the 1960s and 1970s when Māori children who were deemed to be living with ‘unfit’ parents were placed with Pākehā families or institutionalised. This form of child ‘care’ was consistent with assimilative policies that promoted Pākehā nuclear family over whānau.

While Past Caring? values historical and traditional forms of care such as those described by Williams and other contributors, it does not idealise them. Instead, Past Caring? gives a clear-eyed account of the way care has changed over time in Aotearoa, and the gains and losses brought about by social change and second-wave feminism. For instance, the rise of professional care – early childhood education, nursing, aged care and social work, to name a few – meant Barbara Brookes was able to outsource the care of her elderly mother so she could work. She writes, “My mother spent her last years in a small rest home near our house. My academic work took priority over caring in a way that would have been unimaginable in my mother’s life.”

Still, there are downsides to progress. Professional care is most often provided by women and is lowly paid, which means professional carers can’t purchase care for their own families, or be present to provide it themselves. At its worst, regulations and a stretched workforce can make professional care detached and culturally blind. For example, Williams describes how Nan received professional care in Carnarvon Hospital, but found it “culturally alienating and stifling.” Through these stories, Past Caring? makes it clear that whether caring or being cared for, Aotearoa women are still disadvantaged by social structures and the responsibility of care.

The personal narratives of the book are contextualised by a chapter in which Heather Devere looks at two prominent Aotearoa philosophers, Annette Baier and Susan Moller Okin. Devere writes, “Both writers believe that a woman’s perspective needs to be incorporated into traditional philosophical and political theories, and both are critical about the continued omission of female ‘voices’ from the mainstream debate.”

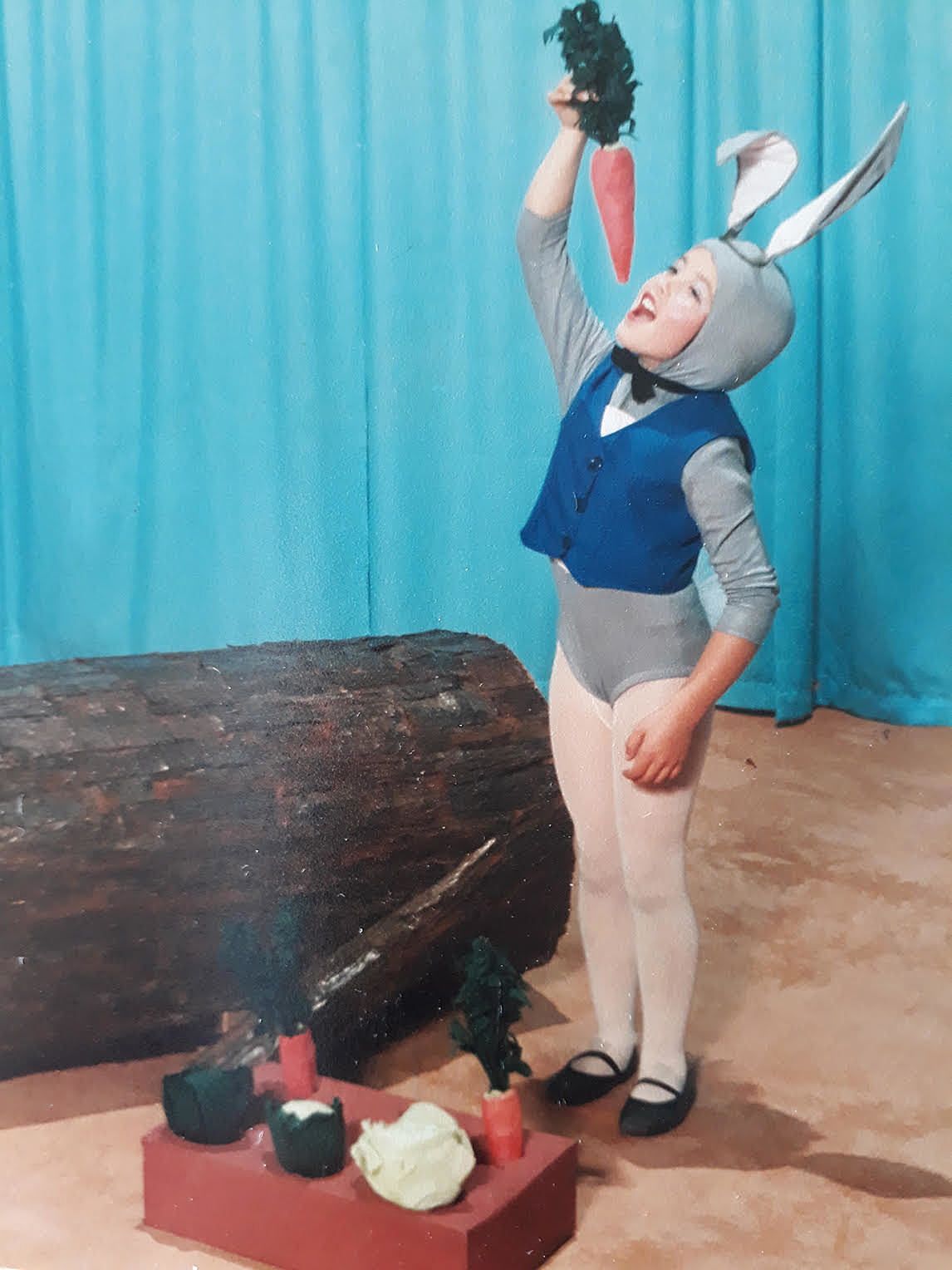

This made me realise that Past Caring? is a quietly subversive book: while undoubtedly an academic volume – no light bedtime reading here – it rejects the impersonal, unemotional, theoretical and, let’s face it, elitist style of academia (which, it can be argued, was created and promoted by white middle- and upper-class men to control access to knowledge). Instead, Past Caring? is personal, engaging, and inclusive, while at the same time showing its academic chops. Each chapter refers to the chapters before, so the book becomes a conversation that slowly builds. There are intimate photographs throughout the book, from a child in a handmade bunny costume to reproductions from Anne Noble’s series ‘Hidden Lives: The work of care’. Together, the photographs say: these issues affect real lives.

Last year I vowed not to write another book review because of the ‘shadow labour’ they always take, but Past Caring? seemed so important to me, especially as a woman living in Aotearoa. I was right to think that. What value it imparts to the women who built Aotearoa, to care given for care’s sake, and to the often invisible domestic care work that underpins and shapes our society.

Past Caring? Women Work and Emotion (February 2019) is published by Otago University Press.