Ko wai ahau? Papatūānuku and I

Miriama Aoake considers mana wāhine in post-colonial Aotearoa.

Miriama Aoake considers mana wāhine in post-colonial Aotearoa.

Content warning: Includes descriptions of domestic violence.

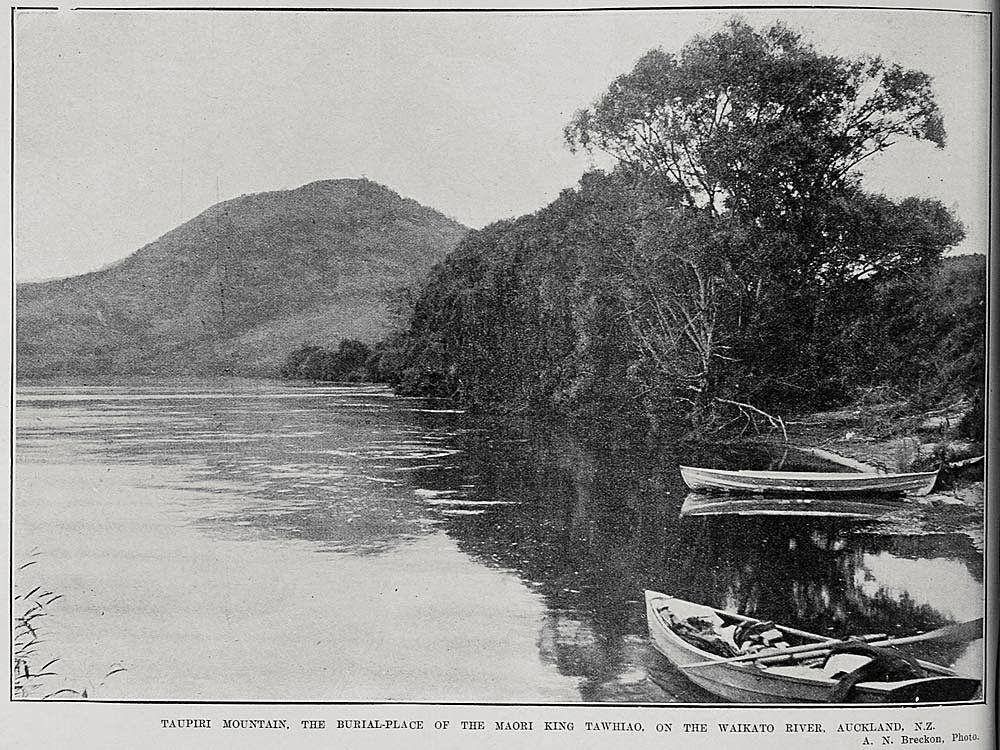

Ko Taupiri te Maunga, Ko Waikato te Awa, Ko Pōtatau te Tangata

Taupiri is the Mountain, Waikato is the River, Pōtatau is the Man

Whenua in Aotearoa is feminine and her name is Papatūānuku. She exists in almost every culture and manifests under several pseudonyms. In Bolivia, she is ratified and protected by the constitution. The notion of land as feminine has persisted relentlessly throughout history, hand in hand with a colonial desire to claim and subjugate her. As a child, I saw the sinuous curves, danger and beauty of the whenua as evidence of a living, breathing wāhine. Her waist, the crevices and valleys between her hips and bosom, were cinched by years of erosion. The flowering and prospering native fauna and flora spoke to her investment in tikanga; the protection of this taonga ensured her health, sustainable growth and fertility. Her diverse environments co-exist; the dehydrated plains of central Otākou, the salty West coast wind, the glare of the Ahipara sun; were all telling of her fragmented self. Her legs the length of the Waikato River. To speak her name, Papatūānuku, was to taste sea-spray, ochre soil and the shade of a kauri.

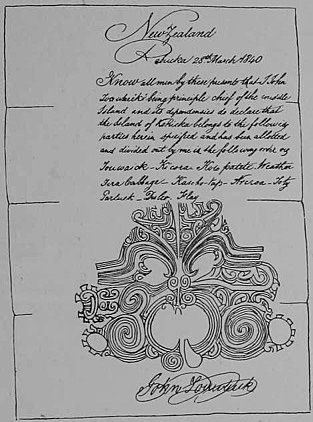

In Māori cosmogony, Papatūānuku was hapu with her son Rūaumoko and his movements inside her womb manifested as her moko kauae, the wrinkles, cracks and fissures of the Earth’s crust. Her moko kauae connects Māori to her, the whenua. For Māori, our moko connects us to both ourselves and our community. Moko is so intrinsic to our cultural blueprint that it was used to sign documents, such as land deeds. Tuhawaiki of Ngai Tahu and great enemy of Rauparaha, used a moko to sign his name to a land grant.

My pain-inducing process is not dissimilar from what many mana wāhine and Papatūānuku herself have been privy to. It is a physical identity marker, and signals maturity and growth of the self. It has observed a resurgence in the last decade. For many, it is undertaken to repair the broken relationship to Papatūānuku and empower cultural identity. It is a tangi for the former self, and a koroneihana for the new self; a self that weaves the shattered fragments of the former together to manufacture a whenua/body that is contingent on resilience. It summons the strength of whakapapa and resurrects the mana wāhine.

The internalised suppression of Te Ao Māori and forfeiting the self to assimilation has made my re-entry into Te Ao Māori traumatic.

The internalised suppression of Te Ao Māori and forfeiting the self to assimilation has made my re-entry into Te Ao Māori traumatic. In the process I have mimicked the colonial desecration of Papatūānuku by the practice of self-harm. Colonial desecration is defined by the erasure of Te Ao Māori, and the establishment of invasive, foreign boundaries that must fall. The scars on my upper left thigh can be seen as the cracks and fissures created from the restlessness within. My scars are both a by-product of this tension between the suppression of self and foreign boundaries. It is an attempt to answer the eternal question, ko wai ahau?

Māori understanding of Papatūānuku as a living body comes with an understanding of kaitiakitanga, that she exists alongside Māori, personified in the geographic terrain of Aotearoa. To apply Marama Muru-Lanning’s assertions of landmarks as a living being, “[rivers] were just part of the way we lived, not something to be controlled or owned.”[1]

In the throes of my post-puberty bodily developments, I came to understand the physical connectedness between Papa and I. Our bodies were in unison, the arch of our backs, the buoyant posterior, strength in our legs; the potential for life between the walls of our thighs. Depending on audience, circumstance, and the presence of danger, Papatūānuku underwent regular metamorphosis as kaitiaki; at once she is the kōura (crayfish), the tuna (eels), a taniwha (river guardian); rivers, streams, lakes and porpoise. She adopts these transitions to appeal to iwi and hapū, warning them of foreboding events. Papatūānuku as kaitiaki had the grim responsibility of being a physical omen. These transitions; adopting different personas depending on audience, was a survival skill embedded in mythology for Māori to revive and utilise in post-colonial Aotearoa.

The role of kaitiaki of my body was a learned behaviour, adopting the selves of others when and if the circumstances require, especially in terms of maintaining a healthy hauora.

Papatūānuku has enabled wāhine like myself to weld together armour in anticipation of a colonial embargo of the body/whenua. The role of kaitiaki of my body was a learned behaviour, adopting the selves of others when and if the circumstances require, especially in terms of maintaining a healthy hauora. Jun Kazama and Kunimitsu, formidable wāhine in the Tekken game series, are assumed when there is a threat to the sustainability of whenua/body or whakapapa. Depending on circumstance, it has become necessary to assume these identities to protect the whenua/body. This subconscious transition signals an omen within myself, that danger is present, and I steel myself accordingly.

The fragmentation of Papatūanuku is analogous with the fragmentation of self. The colonial rupturing of the body/whenua as whole has spawned the splitting of self and the development of multiple identities for survival/surthrival. The bodies of mana wāhine became the legal property of her husband from 1881, and still we pursue the reclamation of our bodies as a blank invitation for colonial penetration. Pākehā men continue to dominate the conversation about Māori women and our bodies. The gaze that says ‘your body is mine, it belongs to me.’ I was ignored, dismissed as kaitiaki of my body, my whenua. I refused to conform until I was beaten to submission.

It was not the Crown seizing land but my ex-boyfriend seizing my neck. Both were violent occasions. Once he violated my whenua my wairua left my body. He subdivided me, redrawing the indigenous boundaries of my being. He expunged my whenua and poisoned the rivers of my mauri with bulimia, creating co-dependence. Away from my body however, my wairua grew strong and reclaimed my whenua; expelling all traces of colonial de:flowering. The mana taurite was restored between my wairua and kaitiaki; and has fortified an impenetrable defence against future colonial attempts to divide and conquer my whenua/body.

Papatūānuku, against her will, became subject to settler reconstruction. Lisa Taouma purports European interest in the Pacific and her bountiful land is synonymous with the construction of the dusky maiden stereotype, “naive, untouched and passively inviting of Western penetration.” Papa’s autonomy was stolen from her, defiled, devalued and defaced. She was forcibly fragmented by irreversible colonial boundaries, becoming an unwilling subject of the Crown.

Papa’s autonomy was stolen from her, defiled, devalued and defaced. She was forcibly fragmented by irreversible colonial boundaries, becoming an unwilling subject of the Crown.

*

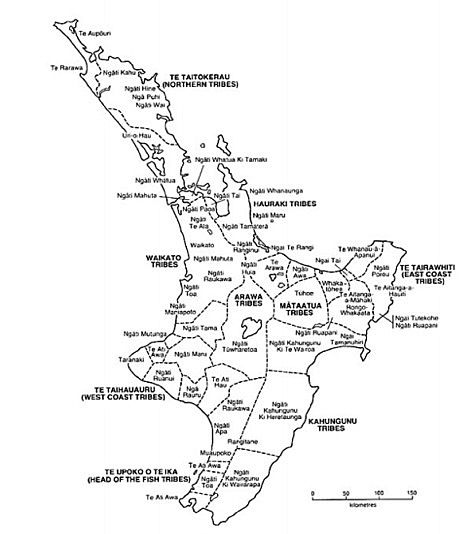

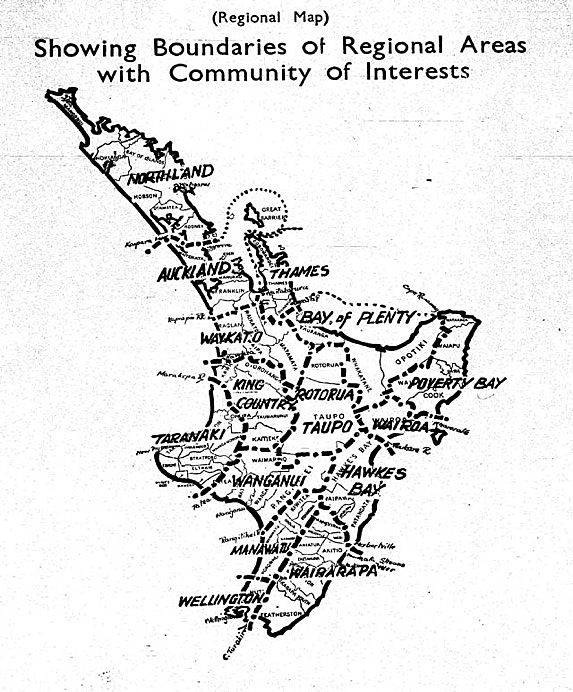

The figures above highlight the different understandings of whenua for Māori and settlers. This is the source of tension in terms of producing often polarising affects of psychogeographic terrain. The re-drawing of boundaries which were almost non-existent pre-contact forced Māori to fragment Papatūānuku. This was exaggerated by the induction of the Waitangi Tribunal process. To streamline claims, the Crown refused to negotiate with hapū. Consequently hapū were swallowed by larger iwi and their only means of reclaiming psychogeographic and physical terrain was to submit to the desires of the constructed collective.

The tension between settler claims to whenua/body/Papatūānuku and Māori, wars at a microcosmic level within me. The Crown seeks to assimilate the mana taurite within into one streamlined, seamless, amorphous self. The domineering Pākehā hegemony dissolves the importance of the Māori world view within the self to promote a monocultural agenda. Colonial methodology evaporates the visibility of tikanga; manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, kotahitanga, rangatiratanga, mohiotanga, maramatanga, tuakana, kaitiakitanga, atuatanga, wairua and mauri. Resistance is the less desirable, more difficult path to restore the principles of tikanga to reclaim the whenua/body. It propels the self to confront not just the individual trauma conceded in the past, but also the collective trauma of the settler process. Most critically, again invoking mana taurite, I must continue to reject colonial claims to whenua/body/offline to preserve the mana taurite between wairua/online and whenua.

Colonial infractions were replicated within the parameters of the whānau unit. Many wāhine held leadership roles pre-European contact, considered taonga to their hapū and iwi to be protected and valued. This is evidenced by whakatauki passed down through oratory. For example, ‘he wāhine, he whenua, ka ngaro te tangata’ means ‘for a woman and land, men perish’. Even during the period of civil unrest, many Māori women took issue with the Crown over the introduction of alcohol. Settlers would import alcohol and once the rangatira were intoxicated, forced them to sign over the deed to the land. Many Māori women sought to implement a prohibition of sorts, to protect collective iwi management of the whenua. Their mana, their manaakitanga, was ever present. The role of kaitiaki was not taken lightly.

Wāhine were clearly integral to the survival of an iwi. The fertile potential nested safely in their womb, much the same as whenua, was vital for hapū and iwi health. This privileging placed much emphasis on the survival of whakapapa. British occupation of Aotearoa denied wāhine their long-held position within the Māori community. Mana tāne mimicked the patriarchal construction and claimed the rigid framework to resign mana wāhine to mere chattels. The literal translation of whenua is both land and placenta, and points to the significance of fostering this relationship. The subsequent desecration of Papatūānuku was duplicated in the whānau model, and mana wāhine were the victims.

The subsequent desecration of Papatūānuku was duplicated in the whānau model, and mana wāhine were the victims.

Mana tāne have been exposed to a cultural amnesia, whereby they have blurred the social structures of Te Ao Māori to fit within the imposed patriarchy introduced by missionaries. The maintenance of these colonial values by mana tāne manifests as physical and mental abuse of mana wāhine and tamariki, who were relegated to the property of mana tāne.

Formerly prized by hapū and iwi as taonga for their ability to birth and strengthen genealogical lines, mana wāhine are now classed as property.

In terms of my sexuality, what was once fluid became rigid. In childhood I mimicked mana tāne in the hopes that my impersonation could be conceived as genuine or legitimate. Before the birth of my brother I assumed the ‘male’ responsibilities and my desires to be seen as male evinced in my adulation of my father. When my brother was born my role was diminished and I was returned to the domestic duties traditionally assigned to women in the Pākehā world view. The immovable boundaries of Western constructs of sexuality prevented me from exploration of sexual self; indoctrinating me to heterosexual normativity. This pattern echoes the stereotypes placed upon Papatūānuku and Māori and Pasifika women as purely feminine, exoticised for the white male gaze. Māori cosmogony needs to be reinvigorated to contextualise the mana taurite between gender within self; that Papa and Ranginui co-exist in Te Ao Marama, they do not compete to dominate one another.

We are daughters of Papa, who have been forcibly fragmented, subjugated, our boundaries redrawn.

In an autoethnographic sense, though I have a strong connection to Papatūānuku, my scars are less traditional. But for my sisters and I, the process of earning our scars is identical. They are my tātai o matariki. We have endured the same settler repercussions as Papatūānuku, etched into our left thighs we bear its weight. We are daughters of Papa, who have been forcibly fragmented, subjugated, our boundaries redrawn. ‘Ko wai ahau? Who am I?’

[1] Muru-Lanning, Marama. ‘The Analogous Boundaries of Ngaati Mahuta, Waikato-Tainui and Kiingitanga. University of Auckland. Pages 9 - 41