Panic On The Streets Of Auckland

In a bookend to May’s Morrissey hip-hop piece, Joe Nunweek wrestles with his demons and decides to go see his teenage hero at the last possible moment.

Despite allocating about 3500 words of the Pantograph Punch’s precious bandwidth to the man and his music this year – despite the rabid fanboyism this surely entails of a grown-ass adult - I cut it pretty fine to even go to Morrissey this weekend. Previously, I just took a conceit and ran with it about the ex-Smiths singer’s affinity to personality-driven chart music (specifically hip-hop), and I still stand by the analogy and the conclusions I reached at the end. More recently, I called him a ‘miserable old git’, which isn’t fair at all, if only because he’s worth an estimated $30 million and can still play municipal peoplefills the size of the Vector Arena – so on the day-to-day, he’s probably not that miserable. The depth of my teenage dial-up obsession with Morrissey gets covered in the link above (suffice to say my knowledge goes deep-cut at least up until 2009’s Years Of Refusal, with the capacity to hum umpteen terrible rarities in between). Why couldn’t I give him a pass for the 16-year-old Joe?

Certainly, it felt like everyone else had. Local press ahead of the star’s first NZ appearance since 1991 was without exception beaming and indulgent – on Thursday night Ali Ikram did a full half-hour Nightline special with him. It seemed less like a sound commercial decision and more like the sort of thing that happens when these matters rest in the hands of ‘creative dads’. No slight to Ikram, who did his homework on a prickly subject, and had to do the whole thing in front of a camera to boot – but it was a tedious travesty. Moz waffled about how the music industry had time and again failed to appreciate and reward his genius (again, $30 million). He dismissed the Royal Family as an irrelevance and proceeded to harp on about them for literally 15 minutes. He evaded the most remotely challenging of questions. This yawning gyre between how I saw Morrissey as a callow youth – in his, as in mine – opened wide. I would never speak to anyone like this. It left a bad taste in my mouth.

So this was Thursday. Friday night, I went to Grimes, whose Visions is among my records of the year. If I need a strained segueway, it’s better than anything Morrissey has done in close to decades. And, well (I hate doing this, hate disrupting the clean omniscient sanctity of writing about seeing something and suddenly being something) - I’ve had a pretty hard couple of months in terms of my health and the health of my family and a bunch of other stuff. I have also deliberately kept myself too busy to process or reflect on any of it, which is great while it lasts but leaves an irresponsible mountain of emotional and physical debt when you approach the agoraphobic wind-down of mid-December.

Separated from my friends, perspiring, disoriented, the whole Powerstation became a sort of broken-glass kaleidoscope before me and all I could think about was whether there was anything left of me when I wasn’t ‘doing things’, anything under an assemblage of tasks to hold on to and recoup and sort my shit out. I had a pretty big anxiety attack and left the show 25 minutes in, and commenced this wild-eyed, shuddering forced march home that I barely remember.

Any sort of utter public defeat (even if this wasn’t public, not really) feels pretty shameful to me. I felt shadowy and frail the next day; I leant forward at my desk to find the final component of a weird post-surgery ritual and missed my chair on the way back down. I just lay there among the cords and cables for a couple of minutes with a cotton bud wedged up my left nostril and watched the bruises flare. I gave out a little, guttural laugh. Then I did the only natural thing I could, went online, and brought a ticket to Morrissey.

Now I’m at Vector, and I don’t know what to make of the crowd. Maybe no one does, because one of the precepts of cultivating this strange, intensely personal relationship with Morrissey is that the template fan becomes you, age sixteen, clumsy and shy. And whatever adult you metamorphosed into afterwards never quite clicks. People that look like builders, portly dads, punks, a guy my age swimming in a thrift suit two sizes beyond him, people who look like they were born immaculately presented, us not so immaculately presented, me. Some of the people are famous and have been on television. My friend sees Defence Minister Jonathan Coleman in the mens’ room. Is he a secret vegetarian in the wilderness of Cabinet? Is he holding out for Morrissey’s 1988 all-patronising clanger, ‘Bengali In Platforms’ (sample refrain: “Life is hard enough when you belong here”)? This is not the template.

Beforehand, we get the straitened aesthetic that has marked most of the man’s work from day one. There’s a huge cyclorama playing vids: “Jean Genie”, Sparks, New York Dolls – his influences seemingly a sacred text that stops before 1980, immune to all amendment. Then it falls away with a flourish and there’s a garbled, doomy litany howling from the speakers, from what’s either a young boy or girl: “Baroness Thatcher…The decline of the NHS….The all-American way…rape…racism…Hillsborough…Bonnie Langford…sexism…Myra Hindley…rednecks…cancer…The Sun newspaper”. He conflates mountains with molehills, the merely banal with the truly horrendous. The messianic trajectory’s clear – in a time of violent upheaval and light entertainment, who will save us? Who’s always been there to save us? I am still not sure if I am going to have a good time.

And they’re out – the band are all wearing All Black jerseys, and later Morrissey himself will wave a black silver fern flag astride the stage front. Even if we can put Morrissey’s questionable race stuff to bed as some sort of hamfisted gangland storytelling, he’s definitely a nationalist. This isn’t a dealbreaker: I mean, later we’ll get to hear ‘Irish Blood, English Heart’, a two-minute pop single that rails against patriotism’s malcontents while longing for some substantive and courageous version of it, and it ends up being one of the highlights of the night. But fuck it, he trades in flags and symbols when he does this stuff, and flags and symbols (esp. corped-out NZRFU ones) are such lead-lined boxes. It’s impossible to x-ray them, to interrogate their exact meaning for good or ill. There are people old enough in the crowd – Morrissey’s age – to have participated in 1981. What do they make of it? It’s a weird fit, a populist gesture to the unpopular kids.

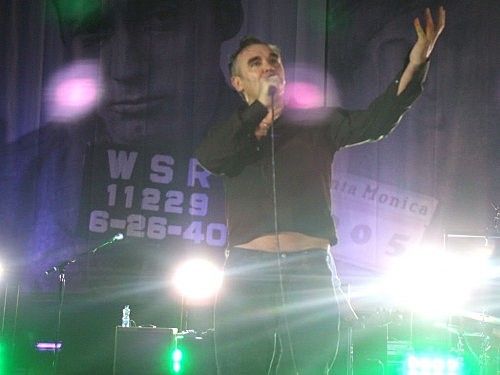

That quiff is receding now, a geographical feature that you finally reach in person and think ‘it seems smaller’, like an echo of what you saw in the tourist guides . Silver gnaws at every side. There’s one angle when he turns partially to his left where his profile looks sharp, forthright, young. He’s not overweight, but he has the condition of his age. I remember his eyes from Melody Maker and NME shoots, and under the thicket of his eyebrows there was a wry, demure ease. Now, there’s a metallic hardness. He is 53 years old and he is playing to people who have waited a minimum of 20 for this.

He doesn’t always move with ease – in old Smiths clips, he unfurls with the measured and untrained grace of something shedding its skin, a glimmer of hope to an audience longing to do the same. This isn't quite the same. He patrols the stage and archly swings a cordless mike in a measure of showman’s artifice, cocks his head for the response of the crowd. Sometimes he loses himself; other times he adopts an awkward stance, like his arms are bracing against the cold on a summer’s night – as if he’s impatiently hectoring us to explain what's wrong with this picture. He does ‘Meat Is Murder’ – my vegan friend notes helpfully that it may have launched the biggest individual cult following of anything he ever did, and though this sounds convincing, it’s also implausible to imagine such a misshapen dirge breeding the devotion it did. Morrissey questions us about our eating habits (“Do you know how animals die?”) in off-kilter meter, pausing with a jaunty twitch to answer himself. (“Heifer whines could be human cries” (Aha! “twitch”)) He’s positively schoolmarmish in front of stock footage of battery chickens. It goes on for ten minutes. A gong is involved.

Elsewhere, though – guys, the singing is exquisite. So many later Morrissey songs are really just tasteful amalgams of Britpop and alt-rock tropes where your mission is to tough out the same torrent of upbeat power-chords to figure out which one it’s going to be – ‘The Youngest Was The Most Loved’? ‘You Have Killed Me’? ‘You’re The One For Me, Fatty’? I love the crude dynamics of early Smiths and that shivering, divisive falsetto, but hearing these live unlocks what’s always been going on. Even on the samiest of songs, he’s usually doing something that departs from the music yet encloses it, that croons to its own internal timing but makes an instant and emphatic sort of sense if you belt along yourself (and we do). Most crucially, there’s a joy that comes through when this famous miserabilist sings, and it eclipses those uneasy gaps in his performance.

Those who follow Morrissey know he doesn’t cop to mistakes or flaws outside of a sort of smug and cosy self-deprecation. Dire albums are marketed by imbeciles, misjudged lyrics are misrepresented by conniving journos, etc. But preternaturally, he knows when he’s on to a winner – so he’s awkward on ‘Meat Is Murder’ even though it’s a stolid Smiths classic, but on 2004’s ‘The First Of The Gang To Die', he’s sublime. It’s an economical distillation of all his ‘thug life’ narratives and a love letter to his massive Hispanic audience – here, it works as a triumphant show of confidence that his flock have followed him into his 21st century comeback.

1994’s ‘Speedway’ is even better. Don’t buy into lazy scribes that treat some of his clunky and overt latter-day imagery as some sort of flashpoint – this is the song where Morrissey outs himself – “All of the rumors/Keeping me grounded/I never said, I never said that they were completely unfounded”. But then he turns around at the denouement and explains why he didn’t earlier, didn’t do so explicitly – to protect a lover. The refrain – I never said, I never said – stops serving as a finger-wagging tease and becomes a desperate badge of loyalty. It’s simply titanic live. I’d forgotten how good some of these solo songs were.

And we get Smiths. We get Smiths – raging takes on ‘Shoplifters…’ and ‘Sweet And Tender Hooligan’, a lambent ‘Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want’, a deafening, swaggering ‘How Soon Is Now?’ coming like a train down a dark tunnel. ‘Still Ill’, which by my reckoning houses about half a dozen of Morrissey’s finest lyrical turns, trills and jangles and comes alive in a way that’s better than being rote classic. If tonight’s the closest anyone will come to seeing these songs as intended, I’m not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

The audience interaction mostly happens during the songs – an instrumental coda for Moz to lean in, shake hands, and receive myriad tokens of appreciation (he makes a face at the gladiola). Every time, a security guard in a football shirt switches into a comical kung-fu stance, shadowing Morrissey’s moves behind a speaker stack. And then at one point everything stops for the weirdest, most evangelical moment of the night, and the mic is passed out to the crowd:

“Morrissey, I just love you so much, and this is my sister, and she loves you as well. I was seasick yet still docked and then came along, and you saved my life so many times and just thankyousomuch.”

“Morrissey, I became a vegetarian because of you.”

“Morrissey you’ve been everything to me. In school I wrote my speech on you and I took first place.”

He stalks between them with what seems like an affected disinterest, raising the stakes for someone to tell him something he doesn’t know. “Anyone else?” There’s something gross and onanistic about it to me, and yet the voices themselves are so heartrending. You don’t get to hear people say what they’ve wanted to say their entire life very often. They don’t get very many opportunities to do it.

I’m moved. Am I wallowing? It makes sense. I’ve heard of parents wary of their teens’ Smiths fixations, of plunging into abject, cavernous despair and shutting everything out, spiraling like an alcoholic to the bottle. But I look around at 40-something men who were builders and lawyers and teachers and stoic until now, with tears streaming down their face as another aging man cavorts over pop music, and it hits me like a tonne. This is insulin, or an inoculation. Science has told us that harmless little taste of what can destroy you is what keeps you going that much longer. At some point in the night, exhausted from panicking in the streets of Auckland, I realized it had been too long since my check-up.

The best is saved to close to the end, the one Smiths song I didn’t mention. Nick Kent’s 1986 NME review of The Queen Is Dead put it briefly, and put it best:

Back to side one, track three.'I Know It's Over' is simply the finest piece of music The Smiths have produced. The song is essentially about loss of innocence or, in my interpretation, of romantic idealism, and is the first piece of music since Frank Sinatra's 'One For My Baby' to have brought me to tears. Morrissey has always been pop's most underrated vocalist, but here his performance is literally devastating. Marr, Rourke, and Joyce keep things spartan, stripped back, gradually building until the climax affords them the rein to almost explode. Yet Morrissey's voice is so totally in control of the dynamics that they shine simply by underpinning his every inflection. The performance and the song are stunning beyond words.

In front of this preening, egotistical star, in front of my teen idol, in spite of the years and the crowds, I forgave him (“It takes guts to be gentle and kind”) I took the melodramatic medicine (“I can feel the soil falling over my head”), pulled a Nick Kent, and finally, willingly tore up.