From the Margins to the Mainstream: Pacific Sisters at Te Papa

Ioana Gordon-Smith on the significance and celebration of the Pacific Sisters at Te Papa.

Ioana Gordon-Smith on the significance and celebration of the Pacific Sisters at Te Papa.

As I reflect on the current state of play of New Zealand art history and art’s histories in New Zealand, and the intriguing potential for new and different narratives, I wonder, I wonder…

For any group working outside the dominant culture, improved representation often happens in waves. You knock back a stereotype, and the next moment-of-making addresses the blind spots that have appeared in its place. Currently, contemporary Pacific Moana art in Aotearoa is thriving. From project spaces to university galleries right through to regional and national art institutions, and even beyond into theatre and online platforms, a range of Pacific makers are presenting diverse practices that encompass the gamut of styles and political positions. The recent Creative New Zealand Pacific Arts Summit fielded a range of funding complaints that only serves to prove that now, more than ever, we have more artists with bigger ambitions, and rightfully so.

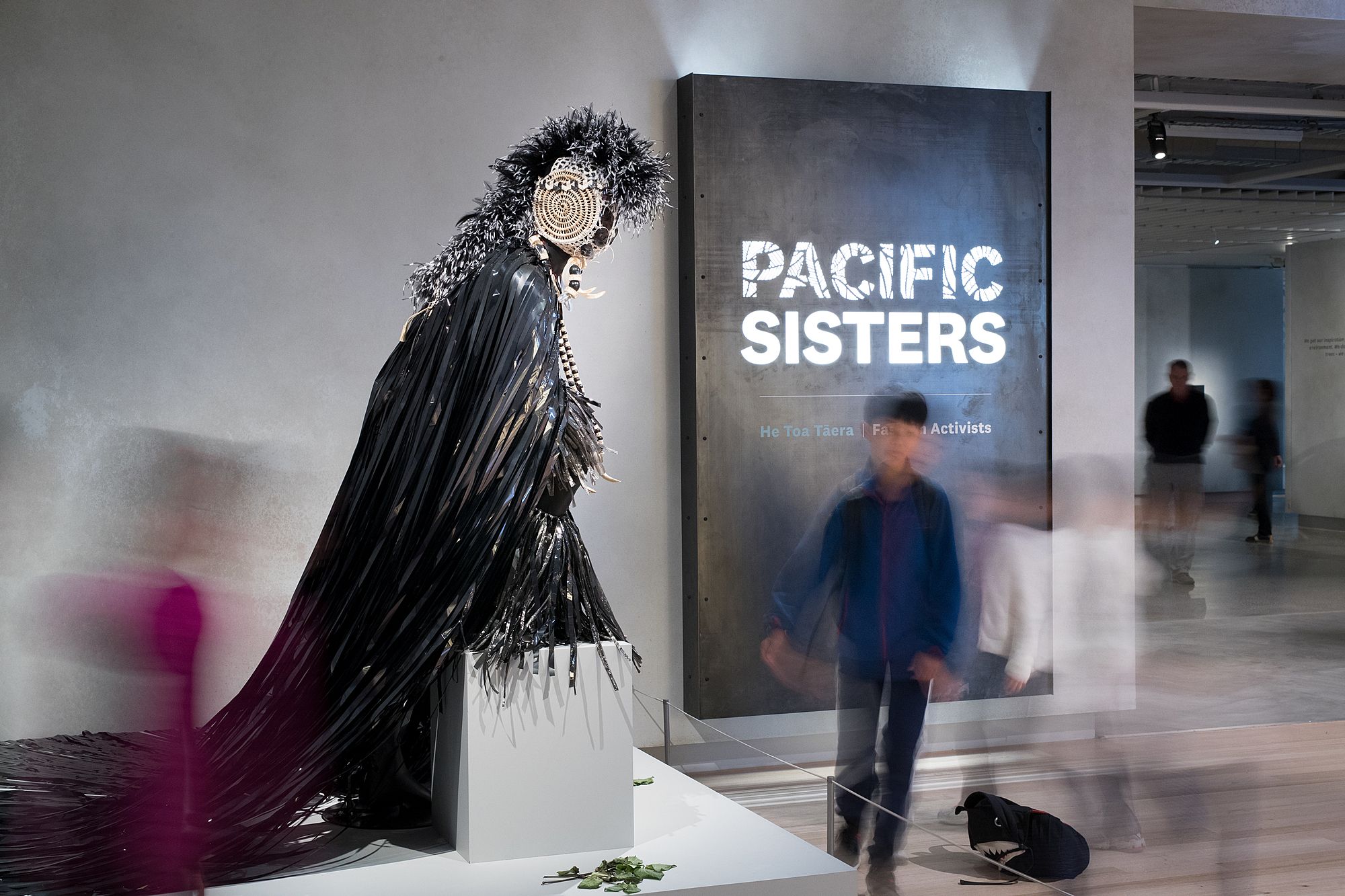

If we can now branch out into a range of different Pacific positions, it’s only because certain barriers were busted before us. Pacific Sisters: Fashion Activists, curated by Nina Tonga, Te Papa’s Curator Pacific Art, is a retrospective exhibition that celebrates the role of the Pacific Sisters as an influential art entity who were instrumental in carving space for Pacific representation. The Pacific Sisters is a loose collective of Māori and Pacific women (and honorary soles) first formed in 1992 by Selina Forsythe, Suzanne Tamaki and Niwhai Tupaea. It has expanded over the years to include, at various times, Rosanna Raymond, Ani O’Neill, Jaunnie ‘Ilolahia, Favaux Valepo, Jeanine Clarkin, Henry Ah-Foo Taripo, Feeonaa Wall, Bethany Edmunds, Selina Haami, Ema Lyon, Sofia Tekela-Smith, Lisa Reihana and many others. It’s a notably pan-Pacific mix, bringing Māori and Pacific Islanders together under one umbrella.

This mainstream bore no relationship to the fierce mana wahine who comprised Pacific Sisters

The Pacific Sisters broke new ground by forging an Aotearoa-bred form of Pacific expression. Until then, that expression was sorely lacking. In the news, Pacific people were only reflected in segments on crime and sports. With some of their members working as models and costumers, the Pacific Sisters keenly felt the lack of brown faces in the fashion industry specifically. Rosanna Raymond recalls sending casting suggestions of beautiful brown women to casting directors only for them to be turned down. As a fair-skinned international model, Rosanna was as exotic as fashion shoots would get.

This mainstream bore no relationship to the fierce mana wahine who comprised Pacific Sisters. Drawing on their diverse backgrounds in film, production, visual arts, fashion and costuming, the Pacific Sisters staged parties and fashion shows in warehouses and nightclubs. They combined fashion with performance, music, installation, multimedia and storytelling to activate their innovative, cross-cultural designs.

Eventually, the Sisters moved from the street to the stage. In 1994, Jim Vivieaere asked the Pacific Sisters to perform at the opening of Bottled Ocean, a major Pacific group exhibition at the Auckland City Art Gallery. It was here that the Sisters developed their iconic Ina and Tuna performance. Different versions of the creation myth of Ina and Tuna can be found across the Pacific. It was actually the shared-but-different versions Rosanna and Ani recalled that sparked the Sisters’ interest in the story as a pan-Pacific but Island-specific story. For their contemporary retelling, the Pacific Sisters relay the Mangaian version, in which a beautiful girl, Ina, falls in love with the shape-shifting eel king, Tuna, who changes into human form for sex then transforms back into the eel to slither away unnoticed by the village. Foreseeing his own death, Tuna tells Ina to chop off his head and plant it. From this spot, the first coconut tree grows.

If the Pacific Sisters’ fashion is activism, it’s because fashion offered a way to combat stereotypes

The resulting performance combines many aspects that are characteristic of the Pacific Sisters practice. The story is drawn from oral history, but retold through contemporary costuming. In the Auckland City Art Gallery iteration, Ani O’Neill played Ina, wearing a blue plastic raffia skirt to evoke water, while Rosanna, as Tuna, wore a coconut-shell puppet and tapa. Over various iterations, the costuming would change as the Sisters revised and updated their performance. Ina and Tuna would also later be adapted to include a 36-channel video installation by Lisa Reihana for the new-media and performance art festival Interdigitate in 1995. It was also proposed for Tala Measina: The 7th Festival of Pacific Arts, which was held in Samoa in 1996. However, the performance was eventually cancelled – and the Sisters removed from the festival – due to complaints from a Māori delegation also participating in Tala Measina. Rosanna notes, “we were rejected by the tangata whenua as representatives…they said they had sole authority over that. Even the delegation from Fiji, which had a coup, had Indian culture as part of their crew.” Eventually the Pacific Sisters were reinstated at the Festival, but by this time they were no longer able to participate as Ani O’Neill and Lisa Reihana were in Australia for the Asia Pacific Triennial.

The story of the Pacific Sisters is entangled with the individual practices of each Sister, and the individual practices the many Pacific creatives they collaborated with. Rosanna Raymond, for example, came into contact with the Pacific Sisters through her role in casting Pacific models for fashion spreads in Workshop, Planet and eventually Fashion Quarterly. The Sisters also individually crossed paths on what came to be known as Style Pasifika. First staged in 1993, Style Pasifika was the first major Pacific Island fashion show to be staged in Aotearoa. It was initially developed by Rosanna, with Feeonaa Wall eventually joining as production support, and other Sisters also involved as either performers or designers.

It was this shared experience in fashion that led the Sisters to instigate projects such as their multimedia fashion spectacle Motu Tangata, which was presented first in Aotearoa as a fundraiser to help the Sisters to attend Tala Measina and then also staged in Samoa. The Motu Tangata fundraiser marked the first time TV show Tagata Pasifika dedicated a whole programme to a single event. If you can find it, watch it. It goes a long way towards capturing some of the atmosphere created by the Sisters for their shows. Models of all sizes swagger down the catwalk to the sounds of local music punctured by the hoots and hollers of a local crowd. It feels like the OG FAFSWAG performances: made by a marginalised community, for their community.

*

Trying to capture the radical energy of the Pacific Sisters in an exhibition is no easy feat. As an amorphous, interdisciplinary collective, the Sisters defy easy summation. Like the eel king they so often reference, the Pacific Sisters are slippery shapeshifters, changing form as needs dictate. Their work is also highly social, entangled with collaborations and crossovers. While their resumé is rife with mentions of major festivals, both national and international, prior to Fashion Activists the Pacific Sisters as a collective have had only a small number of formal exhibitions.

Pacific Sisters: Fashion Activists smartly responds by honing in on the Sisters’ designs. Spread generously across four rooms, the exhibition features over twenty original designs, two videos, two bodies of photographs, and a selection of archival material, including the final segment of Tagata Pasifika’s Motu Tangata coverage. The tight focus on the Pacific Sisters’ own designs offers some serious grounding to the kaupapa that underpinned how they engaged with fashion.

If the Pacific Sisters’ fashion is activism, it’s because fashion offered a way to combat stereotypes. During the time of their formation, narrow ideals of beauty and dress came thick and fast from all corners. In fashion, Pacific faces were virtually non-existent. Perhaps most pervasive was the figure of the ‘Dusky Maiden’. Paintings of nubile, bare-breasted women were made famous through the work of European artists William Hodges, John Webber, and most famously Paul Gaugin. Images of Pacific women have continued to be funnelled through the Western gaze. Sima Urale’s Velvet Dreams (1997) records how these stereotypes continued right through the 1950s with velvet paintings that eroticised half-nude Pacific women. Angela Tiatia’s remarkable solo exhibition Foreign Objects(2012) collected a number of souvenirs sourced using the search term ‘hula girl,’ capturing the ongoing market for images of nubile Pacific woman as tasteless souvenirs.

The room as a whole suggests the power of dress to conjure powerful women – ancestral, futuristic or imagined

Many of the Pacific Sisters’ designs appropriate and parody the ‘Dusky Maiden’ image, but more frequently the Pacific Sisters recall the strong female figures of pre-colonial Polynesia. In her article From Full Dusk to Full Tusk, Mārata Tamaira recalls a long list of strong Polynesian woman ancestors. These include Nāfanua, a Samoan goddess who excelled in warfare; the Māori figures of Hine-nui-te-pō, who crushed Māui to death; the canoe-saving female taniwha, Hine-korako; and Pele, the Hawaiʻian queen of fire and goddess of volcanoes. The Pacific Sisters have in the past made designs that recall important female figures, including Papatūānuku, Kurangaituku and Nāfanua. Sina/Hina/Ina was a recurrent figure for the Pacific Sisters, as a pan-Pacific atua.

The first room in the exhibition is emblazoned with the words “E tūhura ana i te wairua o te wahine toa / Exploring woman as warrior.” Here, the current formation of Pacific Sisters is introduced by individual, larger-than-life studio portraits and an accompanying waistcoat made by that respective Sister. Niwhai Tupaea has described the waistcoat as “the signature to the Pacific Sisters. Drawing on the Pacific’s established style of crossing shells and beads across the torso, the waistcoat is a minor adaptation of traditional adornment techniques. Its basic form could be described as a lei criss-crossed then clasped on the body.” In recalling traditional techniques, Niwhai called the Sisters’ waistcoat “a symbol of protection and identity” that would ground the wearer and connect them to their tīpuna. Within the Pacific Sisters, the waistcoat also oscillates between an expression of individuality and an item that enters each Sister into a shared vernacular.

The room as a whole suggests the power of dress to conjure powerful women – ancestral, futuristic or imagined. On a central plinth, three female mannequins rule over the room. One is arguably the Sisters’ best-known design, 21st Sentry Cyber Sister (1998). Comprising twenty-seven pieces, the figure is an imagined archetype of a female protector. The pieces combine contemporary accessories (a choker and backpack) with traditional items (maro and hula skirt) using a mix of natural and recycled material. As the Sisters say in their artist statement, the 21st Sentry Cyber Sister is a meeting between the past and the future, dedicated to warding off racism.

The Pacific Sisters call their method of adding and layering pieces ‘accessification’ – a word that hums with excess and exaggeration

The Pacific Sisters are interested in more than representing traditions. Growing up as first- and second-generation Pacific Islanders and urban Māori in Aotearoa, their experiences were influenced just as much from street culture and hip hop as they were by oral histories. Faced with nothing that reflected their own experiences, the Pacific Sisters made what they wanted to see (and wear). The resulting designs are quintessential Pacific Sister fusions: urban streetwear made from traditional materials – such as Pacific Babe (1993), which includes a waistcoat-styled crop top and shorts combo made from tapa, complete with accompanying poi – or a traditional dress evoked with synthetic materials, such as a titi (skirt) made from chains or a maro (apron) fashioned from a vintage skirt. More often than not, a single design will include everything. For example, RePATCHtriation (1999-2013) includes pants made from segments of tapa, a t-shirt, a denim sleeveless jacket, and a tiputa (Tahitian garment) made from strips of tapa and cotton dreads.

During a conversation, Rosanna was quick to note that the tapa used was not cut up, but found in pieces along the side of the road. Inorganic collections became treasure troves for the Sisters. Their method of recycling and upcycling is a deliberate nod to sustainable practice and a reminder that Indigenous design is reliant on what materials could be locally sourced and processed. Suzanne Tamaki recounts, for instance, grabbing a dead gannet she saw on the beach, plucking it for its feathers, and then burying it so the skull could be dug up later and used in a necklace. Whether trawling through op shops or combing the beaches, the Sisters pulled from what was around them, and what they could find was indicative of the times. It was inevitable then, that the Pacific Sisters would reflect their own contemporaneity.

The layering of materials, forms and influences means that the Pacific Sisters’ designs eschew Coco Chanel’s advice to “always remove the last thing you’ve put on” in favour of a ‘more is more’ approach. Curator Nina Tonga notes that that no single mannequin in the show wears fewer than ten pieces. The Pacific Sisters call their method of adding and layering pieces ‘accessification’ – a word that hums with excess and exaggeration. Conceptually, ‘accessification’ offers an interesting take on how to represent mixed identities. Conventionally, mixed identities are either reduced to a singularity or divided to make sense of hybridity – think of the term ‘afakasi, for example. Excess feels like a better alternative. The logic provides a defiant way to understand a mixed-race person: as identity doubled, rather than halved.

The Pacific Sisters’ fashion also challenged many views held within Pacific communities. The influence of Christianity on Pacific dress resulted in a move towards conservatism, with most adapted dress forms functioning to modestly cover the body. Modelling braless, walking in translucent clothing, using tapa in non-conventional ways, and pairing traditional materials with a punk-like aesthetic all challenged the conservative tastes of some Pacific viewers.

While clothing offered a way to reimagine and reassert visual codes, images of those same taonga also offered a way into pop culture’s mainstream. Planet magazine published a spread of Pacific Sisters fashion, as part of a feature of Pacific Fashion, in 1993. Within the exhibition, a number of Pacific Sisters archival images are reproduced larger than life, black and white, on light boxes. Notably, these particular images were never printed in their time. “When these were shot, no magazine would print them,” recalls Rosanna, “they were too strong and the models too brown.”

*

A number of Pacific Moana artists continue to grapple with the depiction of the brown body, including Louisa Afoa, Angela Tiatia, Leafa Wilson, Darcell Apelu, and many others. Most obviously, the Pacific Sisters offer a valuable precedent to FAFSWAG. The similarities between the Pacific Sisters and FAFSWAG are uncanny: both are collectives with fluid membership, both experiment with pan-disciplinary forms that nonetheless are founded in performance, gender and dress, and both sprang from a desire to carve out a space of self-determination for identities rendered mostly invisible in the mainstream.

In the press release for Fashion Activists, Ani O’Neill notes “This is just a reminder to the world not to forget about your cool poly-fabulous aunties!” It’s a humorous quip, but it holds an important truth. The Pacific Sisters might loom large as familial legends in the collective memory of the Pacific art community, but how deep and for how long that memory might extend is an important question.

It’s hard to discuss the significance of a retrospective of the Pacific Sisters for posterity without acknowledging that it takes place first at Te Papa Tongarewa. Te Papa’s history of engagement with contemporary art is somewhat marred by its status as a museum-cum-art gallery. The merger of the previous National Art Gallery with a museum gave rise to criticism that art displays would be subservient to a social-history mandate. Even before it opened, criticism came from all corners that its populism would interfere with art displays. Curator Robert Leonard claimed it would be “targeting the lowest common denominator” in a “postmodern collision of values offering little hope for art.”

Some of their early exhibitions seemed to prove that argument. The infamous Parade exhibition placed artworks in amongst a series of other objects from material culture, scandalously placing a Colin McCahon painting next to a Kelvinator fridge. While its postmodern take precluded a historical narrative, running throughout Parade, nonetheless, was a clear notion of ‘kiwi ingenuity.’ Parade came under scathing criticism, which led to an independent government review as well as the exhibition’s eventual removal. It was replaced by the less controversial but equally nationalist Made in New Zealand. The subsequent exhibitions have largely followed suit, using art as a tool to construct a national sense of self. It’s worth remembering that the logo for Te Papa is still a thumbprint, a blunt statement that Te Papa reflects and constructs our national identity.

Their negotiation of a diaspora identity marks their practice as one that could only emerge here

It’s easy to see how the Pacific Sisters could fit into a national narrative. They were a key, galvanising force of a wider Pacific art boom taking place throughout the 1990s. The trickling of many Māori from rural areas towards the city coincided with a new generation of Aotearoa-born Pacific people living in metropolitan areas, too. This growing population of Pacific and Māori urbanites created the conditions for a creative boom. In music, the band Upper Hutt Posse launched a bilingual record in English and Māori, the Voodoo Rhyme syndicate were championing local Auckland acts, DLT hosted a radio show and groups like Sisters Underground and OMC were creating instant classics. Film, theatre and fashion were all taking off. The Pacific Sisters are clearly imprinted within this New Zealand context. Their work is also imprinted by New Zealand. Their negotiation of a diaspora identity marks their practice as one that could only emerge here.

In 2016, Te Papa announced plans to overhaul their art gallery spaces. A major renewal of the museum’s exhibition spaces began with an $8.4 million investment into renovating their contemporary art gallery space. The resulting new wing, Toi Art, is 35 percent larger than the previous exhibition spaces. Te Papa further committed to the commissioning of ten new artworks to mark the occasion.

The rhetoric around Toi Art retains an echo of Te Papa’s nationalist mandate. In a media release, Te Papa Board Chairman Evan Williams asserts that Te Papa is “uniquely placed to tell the story of art in New Zealand.” Te Papa Head of Art Charlotte Davy similarly notes that the new gallery will be a celebration of New Zealand identities. Correspondingly, the new exhibitions “together give a sense of what New Zealand art is, and how it fits within the Pacific.” There are two things interesting about that statement. The first is that the exhibitions aren’t just about showing good art, they’re also intended to show good art that reflects what is distinctive to New Zealand art practice. The second is that New Zealand art, by default, is assumed to have a relationship to the Pacific – however that term might be understood.

New Zealand’s self-identification with the Pacific isn’t something new. Lana Lopesi recently unpacked the history of the ubiquitous tagline of Auckland as the world’s “largest Polynesian city,” while Damon Salesa’s book Island Time (2018) considers both how New Zealand has historically viewed its internal Pacific population, and how New Zealand has looked outwards to position itself in the wider Pacific. Contemporary art institutions have similarly jumped on the Pacific as both a marker of difference and a means to position themselves within a larger geographical frame. The Govett Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, for example, has defined itself as located on the Pacific Rim in order to justify a particular international reach and reputation. The strength of Pacific art in Aotearoa also means that New Zealand art has been able to launch itself as a leader in contemporary Pacific art in the wider region – often to the marginalisation of other Pacific islands. This is most noticeable abroad, where Pacific New Zealand artists often figure in high numbers at the Asia-Pacific Triennial and the Honolulu Biennial.

For all their collaborations, provocations and large-scale productions, the Pacific Sisters are woefully under-written

But if New Zealand contemporary art is clearly claiming Pacific art for national and regional remits, art history isn’t keeping up. There are some key art historical texts – The Frangipani is Dead (2008), Pacific Art Niu Sila (2002) and Speaking in Colour (1997) come to mind – but very little on post-2000 Pacific Moana art in Aotearoa, which has expanded exponentially since the publication those few Pacific texts. The inclusion of Pacific Moana art in the mega art-histories is also noticeably lacking. Early nationalist agendas focused primarily on Pākehā painters asserting an identity independent of the British empire. Recent scholarship is less focused on the concept of New Zealand art, putting stake instead in New Zealand artists succeeding offshore (think Simon Denny and Luke Willis Thompson, or, further back, the art writings of Wystan Curnow). Consequently, as Pandora Fulimalo Pereira and Sean Mallon put it in their introduction to Pacific Art Niu Sila, writing on Pacific art history within Aotearoa is often niche and disparate, traceable mainly through catalogues, reviews, brochures and flyers. It can take some serious effort to trawl through slim writings in an attempt to recover an understanding of a particular artist’s practice and their context.

This is certainly the case for the Pacific Sisters. For all their collaborations, provocations and large-scale productions, the Pacific Sisters are woefully under-written. Only a handful of articles exist about their practice. Partly, this is because the Sisters have each gone on to successfully develop their own individual practices. But the paucity is also indicative of the fact that Pacific art, performance, and 1990s art practices are some of the most under-documented areas of art history in Aotearoa – and the Pacific Sisters combine all three.

Nothing says spotlight or success like a performance leading in the Prime Minister, with the exhibition curator walking at her side

Prior to seeing Fashion Activists, I felt there was an acute danger that their story might be subsumed into a wider social history. However, walking through the new exhibitions, it’s evident that while Te Papa is still nationally-minded, the curators have foregone the social history approach for a ‘best of’ selection. While the two collection exhibitions on the top floor are titled Turangawaewae: Art and New Zealand and Kaleidoscope: Abstract Aotearoa, they both feel less like the chronology shows we might expect and more like big umbrella themes that justify the spacious display of some great art. Downstairs, the other solo exhibitions are dedicated to Michael Parekowhai and Lisa Walker, arguably the most high-profile sculptor and jeweller in Aotearoa respectively. The shows are focused much more clearly on art, and the processes and the intent that underpin it.

Toi Art clearly opened with a line up of who Te Papa considers to be the heavy hitters, and it’s fitting that the Pacific Sisters are in the mix. A lot of that credit needs to go to Nina Tonga. “In the past, no white male curator would have thought to approach us. They probably think we’re a crafty bunch of women,” Rosanna notes in a recent Viva interview. “So it’s great to see a female curator with a Pacific, historic and cultural lens, shining a light on Pacific Island women.” Saliently, Te Papa only recently introduced the role of Curator Pacific Art in 2017 to complement the existing role of Curator Pacific Culture. Having an art historian in a contemporary art curatorial role is significant for the emphasis it puts on art, the artists, and their place within a lineage of Pacific Moana art-making. This emphasis becomes evident in the focus of Fashion Activists, which prioritises the Pacific Sisters’ designs over their networking. For anyone concerned that the Pacific Sisters would be overshadowed by a major institutional moment, the grand opening would have put those fears at ease. It might have been the opening for five exhibitions, but the night clearly belonged to the Pacific Sisters. Nothing says spotlight or success like a performance leading in the Prime Minister, with the exhibition curator walking at her side.

With Toi Art suggesting a potential new emphasis on artistic practice over social-history-driven exhibitions, Pacific Sisters: Fashion Activists is a bold corrective to the blind spots in the art history of Aotearoa. While the show may be celebratory in feel, it is revisionist in function. The reclamation of Pacific art precedents for our contemporary artists is vitally important. As one of the more mainstream-minded of our national institutions, and eager to assert their new direction, Te Papa affords its exhibitions a huge audience. And as a collective who helped take Pacific art mainstream, it seems only fitting that the Pacific Sisters are the ones to take centre stage.