What the dickens is “Outsider” Art?

Hindering artists with a “helping” hand since 1972.

Hindering artists with a “helping” hand since 1972

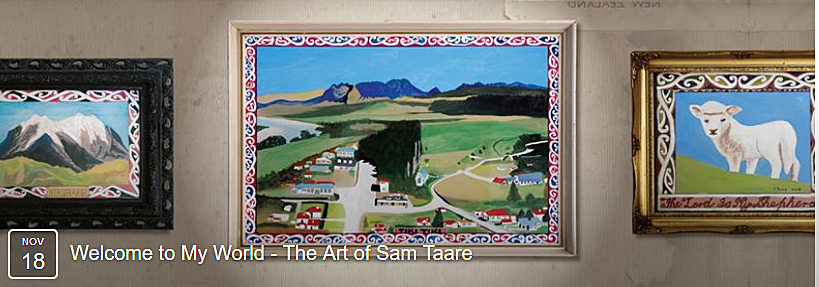

I went to the New Zealand Outsider Art Fair by accident. I liked the look of a painting on Facebook, particularly its kowhaiwhai borders and rather unusual town/country combo. So I went along to the opening of Welcome to My World – The Art of Sam Taare, not knowing it was part of the fair.

When I got to Auckland’s Gus Fisher Gallery, it looked to me like both the Taare exhibition and a larger exhibition – Man Crush by Toby Raine – were stickered with the Fair logo. The logo is artfully faux-distressed or possibly faux-mildewed, suggesting, I dunno, maybe that outsider art – or the outsider artist – is rough, forgotten and decaying.

The fair’s acronym does not dispel that idea.

The outsider brand has been “refreshed” several times in its 44-year history; New York’s own glossy OAF will be 25 years old next month. The outsider artist used to be outside of society itself, on the inside of insane asylums – folk art wasn’t outsider art, for example, it was its own Thing. But the fine arts industry has inflated the outsider concept to encompass most self-taught artists – with more people on the outside, the self-appointed inside makes itself seem more elite. The label creates and imposes a binary: someone’s out so someone’s in. “Outsider art” is a very hard-working, enslaved, slippery little phrase: it is employed to make the work of self-taught artists credible enough to sell, but not so credible that rich collectors call into question the whole art-school-critic-curator-dealer-institution “insider” edifice.

“Insiders” will be smirking when I say that the gallery logo placement led me to peruse Man Crush as if it were OAF art.

“Insiders” will be smirking when I say that the gallery logo placement led me to peruse Man Crush as if it were OAF art. The exhibition’s signs of obsession – thickly-daubed words, fanboy homage, messy altar for ritual sacrifices of canvas scraps – seemed to fit outsider art’s self-taught mad genius stereotype.

But if one of the prerequisites of being an outsider artist is to be self-taught, then Man Crush is, in fact, the apex of insider aspiration: it marks “the conclusion of Toby Raine’s doctoral studies at Elam School of Fine Arts”. I should have paid more attention: the exhibition wasn’t without humour (every subject had a beard) but namechecking celebrity white male creatives – Ozzy, Simon Ingram, Cezanne – makes sense if you have a vested interest in maintaining the patriarchal art hierarchy.

Being taken for outsider art is not necessarily an insult inside the fine arts industry. In fact, successfully aping the outsider is the ultimate insider’s in-joke. It’s high art’s equivalent of Galliano derelicte (as mocked by Zoolander), or of a pair of jeans that’s so faded, stonewashed, and ripped that you wouldn’t even guess they were new. Unless, of course, you knew the brand.

“I struggle a bit with the term ‘outsider’. It can ghettoise artists rather than allow them to be included in the wider conversation.”

– Dealer Tim Melville

Arguably, the original French “Art Brut” concept romanticised the plight of those considered to be mad, and it certainly connected “mad” art with worrying modernist ideals such as purity and authenticity. Now, if an artist’s personal aims, priorities and values have little to do with being lauded at a dealer gallery, the fine art industry tries to colonise their work. It says we shouldn’t be wanting to make work for family and friends and our local car-boot sale; we should be wanting to make art for art historian kudos, for money from the One Per Cent. In one OAF publication, curator Stuart Shepherd states that the “critical purpose” of the fair is “to find ways to position the work of self-taught artists into the everyday economy of the city.”

The key word here is “economy”.

Or, if you’re a self-taught artist welcoming fine arts patronage, then the “outsider” term puts you in your place. It tells you that you’re the poor relation, the pariah, accepted on sufferance but not really Our Sort, not really belonging as One of Us. This idea is so obvious that even OAF general manager Erwin van Asbeck, on another promo brochure, writes that “the term ‘outsider art’ is a contestable one”. But he goes on to say that it “captures the idea of artists who lack the opportunity to participate in establishment spaces….”

But exactly. If some of these artists want this opportunity (as people who bestow the Outsider label assume), why do they lack it? The Outsider label is not the solution, it is part of the problem – it entrenches the divide, it’s a barbed-wire border wall. Dealer Tim Melville – who represents New Zealand’s most well-known outsider artist, Andrew Blythe – puts it most eloquently, albeit on an OAF brochure: “I struggle a bit with the term ‘outsider’. It can ghettoise artists rather than allow them to be included in the wider conversation.”

The Outsider is another word for the Other. And it cements the position of the middle-class and university-educated as the norm.

Asbeck’s promo continues: the outsider artists’ “very distance from the mainstream provides a unique vantage point, free of trends and fashions.” One wonders, then, about artists labeled as outsiders who do get picked up by dealer galleries – are they supposedly sullied and made inauthentic by their interaction with insiders? Are they kept in backyard hermitages away from buyers, preserving their mystique and told to keep themselves “ignorant”?

*

At Man Crush, I found a learned acquaintance drinking in the corner. Did he think there was a class aspect to the outsider label? Oh yes, he replied, if you’re middle-class and self-taught, you’re not even allowed to be an outsider artist; you’re stuck with the “amateur” artist label or, if you’re making money via galleries in hick towns, by selling to farmers or (horrors) to those only moderately well-off, you’re a “commercial” artist.

We went into the other room to seeWelcome to My World.

Taare (1936-2012, Ngāti Porou) lived on the East Cape and in Gisborne, and his exhibition (running until Saturday 17 December) includes biblical and Māori mythical narrative painting; East Cape churches; portraits of Princess Diana and Dame Kiri Te Kanawa in “Maori costume”; the coming of the Endeavour to Poverty Bay; country & western imagery; a waka under the Golden Gate Bridge; and scenes of rural life. A huge amount of commentary can be gleaned from many of the paintings and the way they speak to each other, but my favourites were those which showed herds of farm animals. One favourably compares some cattle to the All Blacks (“you wouldn’t see a more handsome line up than this crop, ready to serve there [sic] country…”) and two showed animals heading for the freezing works through town.

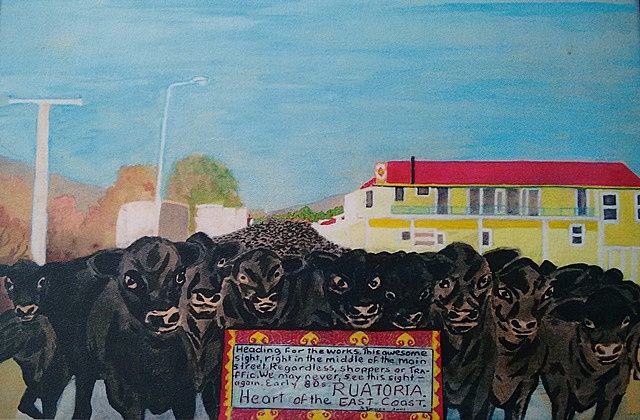

Taare’s caption on the work above reads “Heading for the works. This awesome sight, right in the middle of the main street, Regardless [of] shoppers or Traffic. We may never see this sight again. Early 80s. RUATORIA. Heart of the EAST Coast.”

There is so much going on here: admiration for the beasts, for their thundering unconcern for the monuments of humanity around them, and also no shying away from the fact that the cattle – as awesome and as numerous as they are (filling the road as far as they eye can see) – are also headed for destruction, at the hands of that same humanity. Indeed, the regret of “We may never see this sight again” can be read as regret for the end of the freezing works (shown in another painting), for the end of that way of life on the East Cape. It was painted in 2001, perhaps from a fading photograph, perhaps from lively memory.

It’s the work of someone who knows what they’re doing, whose understanding of visual communication and affect is sophisticated, and who confronts difficult topics head on.

According to the wall blurb, the paintings of Sam Taare “have a simplicity, an openness and lack of demand”. Was the wall blurb describing the same paintings I was looking at?

So how did the exhibition frame such complexity? According to the wall blurb, the paintings of Sam Taare “have a simplicity, an openness and lack of demand”. Was the wall blurb describing the same paintings I was looking at? To my mind, the painting above is unsettling and intellectually stimulating. Okay, so this could be a mere difference in art readings between myself and the exhibition writer – but the viewer is often discouraged from crediting outsider works with “sophistication”, because the word confuses art history knowledge with conceptual or visual intelligence.

In fact, for some, an outsider work is naïve or simple by definition. In his taxonomy of “Self-Taught & Visionary Art in New Zealand”, Shepherd holds that it is not enough to be self-taught in order to be considered an outsider artist. He writes that self-taught artists can “be classified as ...‘self-taught insiders’ if they “are very sophisticatedin their working process and are very attuned to their culture” and if their work shows “a sophisticated involvement and awareness of cultural context and the contemporary art world” (my emphases). (“Outsider” is a moveable feast again: Shepherd mentions Lauren Lysaght as an example of a self-taught insider – yet she’s is promoted in the OAF brochure as an outsider artist.)

The outsider artists are presented as specimens themselves, exhibits who make other exhibits.

The outsider label, then, invites us viewers to distance ourselves from the artist and their art because we are supposedly sophisticated (we’re in a gallery, aren’t we?) and outsider artists, as a species, are supposedly not. So we’re not encouraged to find empathy or common ground with them. The outsider artists are presented as specimens themselves, exhibits who make other exhibits.

I understand that the Gus Fisher Gallery had programmedWelcome to my World, curated by Martin D Page, before the exhibition came under the fair umbrella, before it was labelled outsider. Happily, it is proving a very popular exhibition. So let’s back up a bit, and apply Shepherd’s ‘self-taught insider’ definition to Taare’s work: given his distinctive kowhaiwhai frames and subject matter, his work seems to provide evidence of awareness of artistic traditions and cultural context. So is Taare only an outsider because that context and many of those traditions are Māori? Maybe not: he’s painting themes that have been European canon for centuries – religion, myth, history. So is he an outsider because heis Māori?

Like, exactly how racist does this shit get?

Saying Pacific vernacular art is outsider art is like saying Beethoven, Beyonce and the Patea Māori Club are all outsiders because they didn’t attend the Juilliard School.

Well, one of the OAF exhibitions elsewhere was entitled “Vernacular Oceanic Arts and Crafts from the John Perry Collection”, celebrating “the amalgam of new and traditional materials in various Pacific Island cultures.” This may have been a great exhibition – I don’t know as I wasn’t able to attend – but saying Pacific vernacular art is outsider art, or even self-taught art, is inappropriate, irrelevant and just plain weird. It’s like saying Beethoven, Beyonce and the Patea Māori Club are all outsiders because they didn’t attend the Juilliard School. Actually, given New Zealand’s past and present colonial relationships with the Pacific, the alienation of the art from its intended meaning and context is more pointed than that: It’s a Graham Fletcher painting brought to life. Why are we still pulling these colonising dick moves?

Another example of imposing meaning: the wall blurb (yep, that again) claimed Taare’s works are presented “in whanau-style (an Antipodean variation of salon-style)”. No. “Antipodean” suggests a yearning for the European metropole but newsflash: clusters of paintings in the living rooms and wharenui of Aotearoa are not derived from French Academy hangings. Similar presentations developed independently of each other, referring back to different traditions. Aotearoa is not a variation on a white-created, white-approved theme.

*

OAF promoted itself with at least two brochures: a big one for the dealer and institutional galleries, and a titchy one for all the non-establishment pop-up exhibitions. There are hierarchies of outsider, it seems – and men are more welcome in the upper-outer echelons than women, if the OAF establishment programme is anything to go by.

Showing up the redundancy and parasitical nature of the outsider label... it was artists in the hood displaying their art to their neighbours, K Road insiders to K Road insiders.

The non-establishment pop-up exhibitions I saw were great. They displayed outsider art to other fine art outsiders in non-fine-art spaces, showing up the redundancy and parasitical nature of the outsider label. Up on Karangahape Road, several shop windows displayed the work of artists who work just down the road at Toi Ora Live Art Trust which promotes creative pursuits in mental health recovery. The pop-ups allowed the artists’ work to be visible in their own community – it was artists in the hood displaying their art to their neighbours, K Road insiders to K Road insiders.

One Toi Ora artist – Selwyn Vercoe – is now also a curator, building a profile and working with the likes of Fiona Pardington. His “People of Karangahape Road” group exhibition opened at RM during the Outsider Art Fair, but it was not an OAF exhibition. Vercoe identifies as an outsider artist – which he defines solely as self-taught – but he identified the other artists involved in the exhibition as non-outsiders.

Wouldn’t it be nice if the labels didn’t suggest an overt hierarchy, if Vercoe and his colleagues and collaborators could approach each other on their own terms?

Art industry insiders and institutions “discover" outsider artists, and colonise their work

The last weekend of the fair, I took the train to All Goods Whau Arts Space in Avondale, because arts collective Whau the People had advertised an exhibition of robot art for OAF. I thought this was extremely clever of them, because the robot becomes the outsider artist, and what is questioned is human acceptance of “her” art. To be an insider, all you have to do is be alive – there’s no elitist hierarchy here, maybe just a little carbon-based lifeform parochialism. Confirming the bio-inclusivity, on the first weekend anybody at all could come and take digital photographs for the robot to “interpret” and “re-draw”.

However, when I got to the space, the robot art had been taken down and a Variety charity book stall had taken over the front space (I couldn’t be too grumpy: Death, Duck and the Tulip was $4). But in the second room, I found the Open Brief poster show – an Urbanesia show, not an OAF one – and staring me straight in the eyes at the entrance was this:

Siliga David Setoga’s spoof Tui ad is most overtly about geographical colonisation – his other characteristically clever, punchy posters in the show give the same treatment to “sorry” and “settled”. But because I was thinking about outsider art, the first thing the poster made me think of was art industry insiders and institutions “discovering” outsider artists, and colonising their work. The outsider artist label speaks of patronising conceit – and shows a very unsophisticated understanding of how words work.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Sanderson Gallery, for example, represents a number of self-taught artists without the dubious assistance of the outsider label. Given that the problems with the phrase are admitted by its merchants, let’s put “outsider art” to rest, and try to consider artists – all of them, even those unfortunate enough to have been exposed to fashions and trends at art school – on their own terms.

Welcome to My World - The Art of Sam Taare

Gus Fisher Gallery, Shortland Street, Auckland

18 November to 17 December 2016