Outside Looking In: Remembering James K Baxter and Jerusalem

Elizabeth Beattie follows the radical NZ poet's steps to the Whanganui River

‘John - heart of my heart - I have news that will bring joy. To some sorrow, but to you joy alone.

The lord…[has] called me to go to Jerusalem.’

-James K. Baxter, Letter to John Weir, March 1968

Waking from a stirring dream one evening in 1968, poet James K Baxter (Jim, or Hemi to his friends) sat down to pen a letter to his close friend, priest and academic John Weir.

The two men wrote regularly, having initially met via posted correspondence. When Weir was a young man contemplating a life in the seminary, he had plucked up the courage to send Baxter one of his poems. Baxter’s slightly ‘unusual’ response, Weir recalls, was to ask that they become friends. Subsequently over the years, and through an exchange of words and ideas, they had become exactly that.

In this particular letter, written during nighttime, one imagines with a sense of urgency, Baxter explained that he had experienced a vivid vision calling him to Jerusalem. He had woken feeling shaken, and grabbed his bible, letting the heavy book fall open. At random, the first sentence his eyes had rested on was a direction from god sending his disciples to Jerusalem.

The vision which he described to Weir became the inspiration for Baxter to travel up the North Island to make a space in society for young, struggling people in need.

Jerusalem, or Hiruhārama, is a fertile piece of land nestled where the Whanganui River curves around into a bend. In 1892 the order of the Sisters of Compassion was established there, along with the tiny St Joseph’s Church, designed by Wellington architect Thomas Turnbull.

At first glance, Baxter’s draw to Jerusalem may have appeared to be random, but his Catholic faith and interest in Māori culture had made a significant impact on the way he lived his life. To his mind, Jerusalem was a place that embodied both these influences.

Armed with a plan, and a desire to do good, the poet cast aside both money and the meagre possessions he’d earned from a life of sporadic fellowships and commissions, starting his pilgrimage northward. Through back roads and main roads, with stop offs along the journey, writing along the way.

*

‘In contradiction.… I was born.’

-Baxter, 'Home Thoughts', 1962

Born the son of a conscientious objector father and an academic mother, by most accounts, Baxter was a solitary child, and socially withdrawn. As a way with connecting with his surroundings he relied on his keen observation skills, which would drive a prolific writing output of three to four poems a week throughout his entire life.

“He was always an outsider, that happened from the very beginning,” says Weir. “He was a very clever child, in some respects more than his teachers.”

Weir notes that Baxter’s political views, even as a teenager, put him at odds again with the political climate in New Zealand at that time: “[Many of the] people around him when he was growing up…wanted New Zealand engaged in a world war. [Baxter] was a pacifist and didn’t want to be engaged, just like his father.

“He then went off to school in England for two years, where he was the only New Zealander in an English school, then he came back to New Zealand and he was now an ‘immigrant’, and it went on and on.”

By the time Baxter was entering his late teens, he was beginning to develop his unique writing style. "A Man", which he wrote at age sixteen, foreshadows his later role of social commentator and humanitarian interests:

‘For I die in this man. O comrade, even I / Shared

In your peace and vision under a homely sky: / In you I suffer, in you I die’

But for all his prolific written output and certainty with words, Baxter was grappling with his own identity, confidence, and sense of belonging. His early relationships with women didn’t flourish naturally the way those of his more conventional peers appeared to, and the early tastes of intimate rejection shook his confidence - yet another part of his life where he was perpetually on the outer.

The same year his first collection of poems Beyond the Palisade was published, the shy 18-year-old began his studies at the University of Otago. He later referred to his foray into academia as a “long, unsuccessful love affair with Higher Learning” in a 1961 essay (ironically, written for the Victoria University College Review). Although his start to university was rocky, respect for Baxter’s poetry was growing. His creative output remained constant, despite his growing alcohol addiction, which buried him in sullen moods and depressed, isolated nights. As it has always been in Dunedin, there were opportunities for young men unfamiliar with sudden freedom to drink every day and night. In the Victoria University essay, he remembered that “the irrigating river of alcohol flowed continually through my veins.”

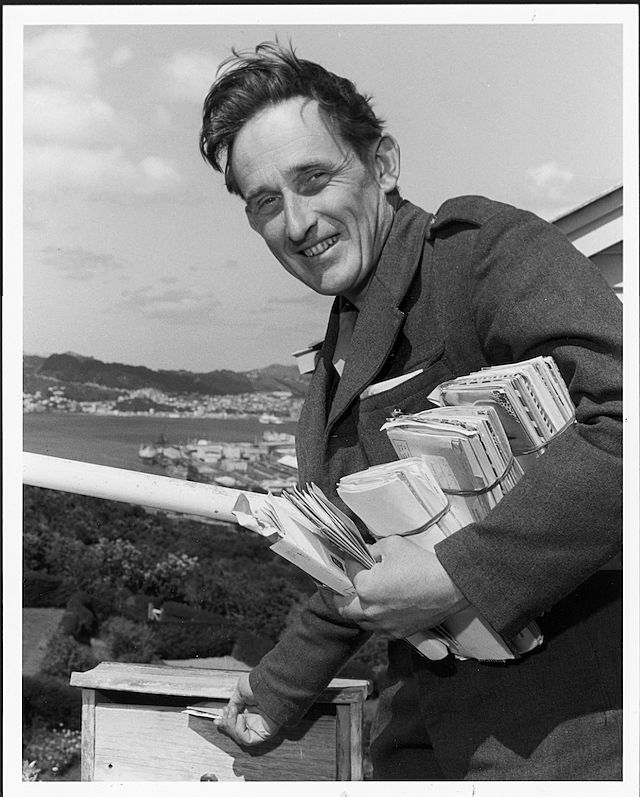

Finally completing his degree at Victoria University, Baxter started working as a teacher. For the man whose employment had ranged from postman, to farmhand, to worker in an iron-rolling mill, to worker in a slaughterhouse, teaching provided regular hours and stable income for the first time in his adult life.

It was also around this time that Baxter quelled his drinking problem, becoming an active Alcoholics Anonymous member in 1954. He remained sober for the rest of his life. His personal experience with addiction gave him unique insight into substance dependence; his sobriety gave him the motivation to help others who remained so. Baxter’s lifestyle at this time drew him away from the kind of places – academia, for one – where alcohol flowed freely.

Between September 1958 and April 1959 Baxter was granted a UNESCO Fellowship, which led him to Japan and then to India to study educational publishing. His experience living in India shaped both his writing and his perspective.

Now from the Muslim quarter rise

Dissolving cries and arabesques of fire

From braziers heated with dry cattle-dung.

Tomb-dwellers, women in black shawls,

With pots of dirty brass

Pad to the well, and chatter in the sun.

Eagles have bathed their wings at the ocean streams.

In a cold taxi coming from the mass

With Bertha in her blue silk dress

I think of money. Lepers in the gateway

Hold out their cups and bandaged palms.

Their eyes like desert cisterns burn.

Each soul a moonless oubliette

Waiting for the last great Key to turn.

-Baxter, "This Indian Morning", 1959

Returning from this trip, Baxter returned to his homeland ill at ease by the poverty he had seen and saw replicated in parts of New Zealand. He was particularly concerned about the displacement of Māori - deprived of any share of the decade's agricultural boom in the countryside, atomised and impoverished in the cities.

His poetry had already been expressing his passion, activism, and anger eloquently – the trip merely focused it. Writing on one of the final executions in New Zealand before it abolished the death penalty in 1961, he linked tyranny at home to tyranny abroad. The Vietnam War, and an unprecedented backlash of public fury, were around the corner.

Oh some have killed in angry love

And some have killed in hate,

And some have killed in foreign lands

To serve the business state.

The hangman's hands are abstract hands

Though sudden death they bring --

"The hangman keeps our country pure,"

Says Harry Fat the king.

-Baxter, 1956, 'A Rope for Harry Fat'

As Baxter’s works and opinions became more unbridled, he came to be viewed as a social activist, speaking out about the need to do more for New Zealanders struggling with addiction, poverty, and discrimination. Weir explains that Baxter’s experience of perpetually feeling on the exterior of NZ society gave him a freedom to speak his beliefs.

“The fact that he was an outsider and had been all his life, caused him to recognise the needs of other outsiders such as drug addicts, the unemployed, people with mental health issues, in other words the people that came to Jerusalem. He felt he was a man of their tribe - the tribe of the outsider.”

This recognition for others and their needs was reciprocal. Where he had previously sought refuge in getting “asleep dead-drunk” Baxter now combated his own chronic loneliness by seeking out the friendship of others.

“Jim was very lonely for much of his life, he felt a deep need for friendship and for love. He recognised that other people on the margins of society, were also lonely and the thing that would help them most would be friendship and love. That really became the basis of what happened at Jerusalem.”

*

“It is my opinion that if we turned away any guest from the door – mad or sane, drunk or sober, male or female, young or old – then we would be excluding God from the house. The guest should be welcomed with signs of love, and given food and drink – even if there is very little to eat in the house – and given a place to lie down. If guests choose to stay for any length of time, they should not be asked to contribute money or perform tasks – though their help should be welcomed if they offer it.'”

-Baxter, 'The Love Of The Many', from a 6-part series of Lenten Addresses given on Radio New Zealand National in 1971. They can now be found in Volume 3 of Weir's Complete Prose anthology.

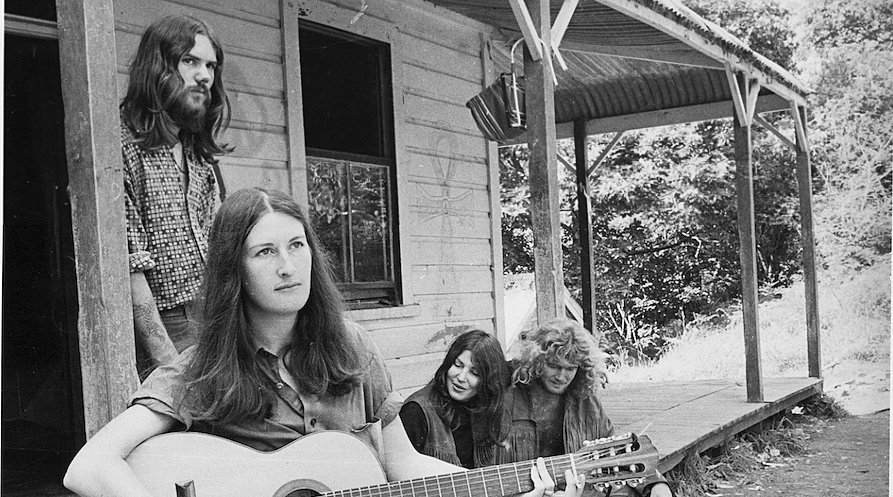

Ted Hodder was in his late teens and travelling around the North Island. One day, on an inter-city bus, he got talking to a fellow traveller who had been dipping in and out of commune life for several months. Hodder had already heard vaguely about Jerusalem before his conversation, but the talk piqued his interests.He decided to see what it was all about.

“[My] first impressions was that it was cool, nice hippy type people. The first day I arrived there I was offered a bath, and I was the sixth one in the same bath!” he remembers with a chuckle.

Baxter was by then well and truly ensconced in Jerusalem life and led the welcome party. Hodder recalls him as as a down to earth man who was genteel and easy going.

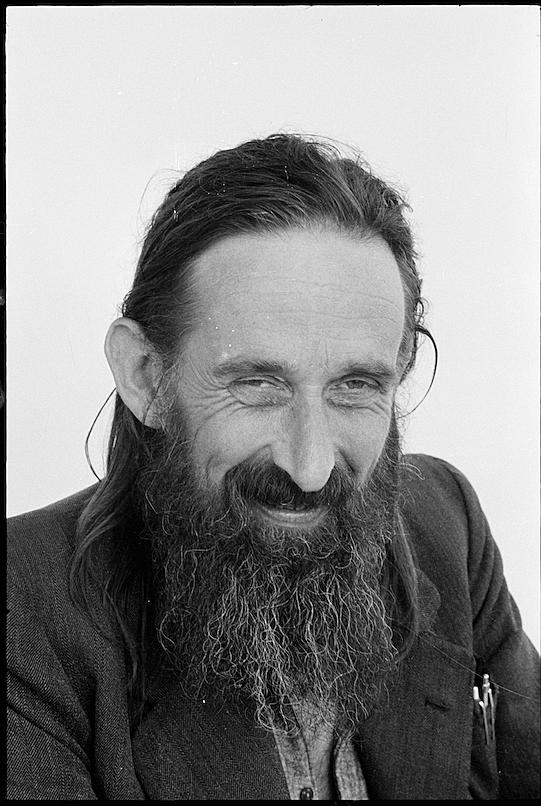

“[Baxter] was an older guy, wrinkles and everything, amongst these younger people. He had long hair and a beard, he dressed roughly with a rough old suit that had obviously been picked out of a recycling shop. He did make an impression on me. I remember reading that he found it quite hard to just walk up to people and hug them, but he did [embrace] me, he said ‘how you doing?’ and I hugged him back, then we went up to Jerusalem.”

They walked in a group down to the communal houses, where the new arrivals were welcomed warmly. “In the kitchen, in the bottom house, everyone got out their guitars, there were about five of them, and [they sung] Alice’s Restaurant by Arlo Guthrie, that goes for about 15 minutes, and I remember them singing it word for word, it was absolutely beautiful”.

*

“It is the salutation of the poor man at the gate of the pā [Māori village] the one who has no credentials. This is the pa of the dead, and I think they do receive me. I kneel on the wet grass, beside the concrete tomb of the kaumātua, the Māori elder who lived in the house before us, and say prayers, both in Māori and in English, praying that the souls of the Māori dead may have light and peace and asking them to bear with our stupidity and put the coat of their aroha over us.”

-Baxter, Jerusalem daybook, 1971

Founded on the ideals of aroha and friendship, the underlying structure of life at the commune was in practice rather anarchic. Baxter was not forceful in his leadership. He believed in negotiating decisions communally, a process which could be slow and unproductive.

“Most people like things cut and dry, whereas his argument was life is not cut and dry,” said Weir. “He believed that people should make their own choices. He didn’t enforce rules, he made suggestions that people talk to each other and make their own decisions or come to a community conclusion.”

In this occasionally haphazard way, his intention was to create a democratic and loving environment, with a focus on building understanding and reciprocal support. “His biographer Frank McKay once asked him; ‘Jim, when these young people come to Jerusalem what do you do with them?’ Baxter’s answer to McKay was; ‘I give them my friendship and they give me theirs.’”

This simple founding premise of Jerusalem made it a haven for many, from middle-class dropouts, travellers, unemployed youth, addicts, and those generally searching. It was an open door community, with hospitality offered freely, and Baxter didn’t turn anyone away.

“If they arrived and decided to say a night, or a year, that’s what they stayed. If they decided to they weren't going to work, and were just going to eat meals and sleep, then that’s what they did,” said Weir.

“He didn’t provide any rules. He said there were too many rules outside - and the young people who were coming to the community were coming to get away from the rules.”

However, Hodder’s memories of Baxter as an easygoing and open-minded man also encompass some of the stereotypes of the 1970s commune lifestyle, particularly the poet’s free attitudes towards sex.

He chuckles over the memory of discovering a relaxed Baxter, by this stage well into his 40’s and married, curled up in bed with a blushing young woman in her 20s. “He was open minded.”

*

Mattresses were laid out across the floor and food was shared communally. When Baxter was not at Jerusalem, he was out working and raising funds to support the community.

By many accounts, around that time, life at the commune was harmonious, if a little chaotic. Yet relationships and friendships grew organically under the close lifestyle. In 2012, Dorothy Scott wrote an autobiographical piece for The New Zealand Society of Authors recalling her trip back from a photographic convention where she and some friends stopped off at Jerusalem briefly, spur of the moment, and stayed for a cup of tea:

“James, in his shabby old coat, welcomed us in and took us into the communal kitchen with its stacked rows of tinned food, tins of sardines and mismatched crockery and introduced us to a couple of teen-aged boys, long-haired and unshaven, but very clean. They offered us a cup of tea and it would have been ungracious and rude to refuse. We were handed the milky tea in a chipped, much used blue enamel mug to share among us….

“We sat out in the sun talking, beside an open door to a room with much-battered interior walls. James explained that sometimes when drug withdrawal symptoms became too tough to handle, a sufferer would need the chance to lash out, hurt themselves, anything, to release the tension. They could voluntarily go into that room, rave and shout, kick in walls, whatever would help at the time. While we were sitting there a boy, obviously distressed, came up to James. He excused himself, took the lad a small distance away and sat down with his arm across the youngster’s shoulders, talking quietly. You try not to watch in these circumstances, but as the soothing voice continued, so the tension gradually left the thin shoulders of the boy. Eventually he stood up and moved off.

“This room, built with love, had been created by kids who had been as low as it was possible to go. They’d been gathered from under bridges, squatting in derelict houses, roaming the streets, un-loved and shunned by all"

Meeting Baxter left an impression on Scott, who said of the poet: “He was such a special man – compassionate and with a deep understanding of those who lived in the commune at Jerusalem. I have never forgotten the time spent with him that day.”

*

‘The Māori Jesus said, 'Man,

From now on the sun will shine.’

He did no miracles;

He played the guitar sitting on the ground.’

-Baxter, "Māori Jesus" – c.1966

As Baxter’s popularity drew larger and larger crowds it became a challenge to fit everybody into the limited space, and provide them with food. For the poet, this meant more time, spent fundraising and appearing at engagements in order to get more resources for the commune’s good work.

The rigorous lifestyle of travelling, giving public talks, and networking must have been hard on the reticent Baxter, who had to work for days at a time only to return to what was an increasingly challenging environment at Jerusalem.

Weir agrees that “things did become more chaotic then Jim would have liked.” Many of Jerusalem’s visitors were, like Hodder, young and transitory, a lifestyle that made it hard for progress.

Hodder himself spent about 18 months to-ing and fro-ing between travel around New Zealand, and returning to Jerusalem. Over that time Jerusalem remained much the same, though growing in size.

“There was no progress,” said Hodder. “Nobody did any work, they sat around and waited for someone else to do it. We threw ourselves into [that] situation, living in close proximity with everyone else, and had a pretty basic sort of lifestyle.”

The locals were also becoming increasingly disgruntled with the disorganised structure of of the commune. One man accosted Baxter in the street, viciously tugging on his beard and threatening to burn down the houses erected on the land.

For Baxter, who had visionary ideals of Jerusalem bringing peace to the disillusioned, providing unity, and nourishing those in poverty, this stagnancy must have been disheartening.

“I think he was a little bit disappointed with how it all ended [up],” says Hodder. [It] was a bit sad, but it was falling to pieces socially.

“In one way it was a really good experience to go through,” he reflects. “In another way it was a waste of time purely because we didn’t make any progress other than going through that life stage…It was a really good experience, and it wasn’t. Bittersweet, it was really bittersweet times,”

But for Jerusalem’s rocky relationships with the locals and its lack of progress, a tight-knit culture was built within the community between those who did their time. For Hodder, and many of the individuals who journeyed through Jerusalem, it was still a time of growth, self-exploration, and reflection.

“I was a real messed up kid, really messed up. I was going through that stage from child to adult and dealing with issues and problems myself, which is why I left in the end. [But] I remember this one day sitting on the hill at dawn looking over the [Jerusalem] valley and everything, magpies were singing and the sun coming up. That was a pretty special moment.”

In September 1971, under pressure from the locals and The Whanganui City Council and after a protracted series of town meetings at which both farmers and iwi raised their objections, the Jerusalem commune officially disbanded.

*

As time passed, Baxter and a smaller group were invited back the following year on the condition that numbers were restricted, and that only 10 people would be allowed to live on the premises at one time. Although Baxter did return, his ties with Jerusalem were waning.

“His move to Auckland in September 1972 had a degree of permanence about it because [Baxter] farewelled Jerusalem and appointed one of the residents to be in charge,” remembered Weir.

A naturally restless soul, Baxter’s final phase of work was mainly with drug addicts. He sporadically lived with a number off them at Boyle Crescent in Grafton, Auckland in his final years.

“He changed the nature of the group he worked for,” said Weir, noting that throughout his life Baxter had taken consistent interest in alcoholics and prisoners.

He arrived in Auckland wearing sandals, shaggy haired, and bearded, Catholic rosary beads hanging round his neck. Years of posthumous artistic depictions and retrospectives have given us an established, sanctified image of Baxter, but to CBD dwellers, he must have looked more like a vagrant than an award-winning scholar and poet. And indeed, in Baxter’s experience, many people who were unacquainted with his reputation treated him as such. Children called out when they saw him, taunting him with names like 'Moses’ or ‘Jesus'. People averted their eyes from his rough and ragged appearance, as though it were embarrassing. The more tactless would linger over his thrift store clothes and unkemptness. If Auckland didn’t appear to take kindly to Baxter, the poet reciprocated the feeling, starting his 1972 poem “Ode to Auckland” with the infamous first line;

‘Auckland, you great asshole…’

Weir explains that Baxter’s rough appearance was purposeful. “He adopted what he called a ‘uniform of poverty.’ He said the police have their uniform, people who work in businesses, they dress up to go to work, that’s their uniform, and school pupils have their uniform, and he said I have my uniform.

“But that uniform of poverty that Baxter spoke about put him at odds with much of conventional society with the collar and tie brigade. So again, it was a point of demarcation and division in society...[People] felt that they themselves, and their own values, were coming under implicit criticism.”

Baxter could never be one to be considered conventional. His focus was connection, change, identity, language and the people at this stage he was seeking to connect, who happened to be wearing similarly ‘dividing’ attire, though not by the same choice. “The people who were threatened though weren’t the people in need,” Weir reflects. “They were people in middle class New Zealand society who might be quite well off financially, and have a nice house and solid job and so on. It was those people, the very respectable people in society that responded in one of two ways, either they became supporters of Baxter… or they were utterly opposed to him and saw him as derelict.”

*

‘[Poets] should remain as a cell of good living in a corrupt society, and in this situation by writing and example attempt to change it.’

-Baxter, from a speech at the New Zealand Writers’ Conference, Christchurch, May 1951

For all the recognition, awards, and respect Baxter received for his poetry, he retained his role as the underdog. His words remained fiercely challenging and grew ever-fuller with visceral imagery, his poems dictated by his basic surroundings. As ‘Ode to Auckland’ escalates, he writes ‘…The rich are eating the flesh of the poor / Without even knowing it…’

Even now, Baxter’s challenge to society can be felt in through his words, which combat each other, demanding attention, crying for justice, bitter for the pain of others, and for his own. His poems do not sit politely, words daintily stacked up one after the other, instead they roar, sob, howl, and sing. The rawness of his work is at odds with the tentative warmth of the welcome Ted Hodder describes – peers and archival recordings reveal a mild man, with a slightly English-toned whimsical speaking voice with a swaying cadence when he talked or read, indented by his boyhood years abroad.

If his poems can seem didactic, Weir remembers Baxter as a good friend, challenging, but with a great deal of humility. “By temperament [Baxter] was a gentle type of person, but he could also be very stubborn. Stubborn over principles and over the rights of other people, but he was not stubborn about himself, or how he was treated. If people insulted him for example, he would say ‘I deserve that’. He used to accept criticism quite freely.”

Despite his sobriety, his work ethic can only have shortened his life. Weir refers this aspect as ‘Baxter’s heroic side’.

*

‘At the end of life God presses down a seal

On the wax of the soul. If the wax is warm

'It receives the mark; if not, it is crushed to powder' -

So be it. My own heart may yet be my coffin.’

-

- Baxter, 'Te Whiore o te Kuri', 1972

The acts of mercy took their toll inexorably. By September 1972, Baxter’s health was visibly declining. Friends recall that his cheeks were hollow, his food unpredictable, his body pockmarked by lifestyle, his eyes marked with his struggle and fight. The week before he died, he visited Mt Eden Prison, talking and spending time with prisoners. Through his dedication to work with those in need, Weir remarked, he often overlooked his own.

On 22 October, 1972 on a Spring Sunday evening, Baxter’s heart stopped beating. He was pronounced dead, having suffered a coronary thrombosis earlier in the day at age 46. His body was escorted by his family back to Jerusalem, where he was honoured with a dual full Māori tangihanga and requiem mass. Over 800 people attended his funeral, including Weir, the young priest who was asked to give the homily. In the end, he was too choked up to do so.

“Jim was my dearest friend,” he says some 43 years later. “He’s one of the dearest friends I’ve ever had in my life. He had a great deal of love for me and I have a great deal of love for him.”

Recognising his death, the Dominion's billboards opted for an epigraph that meant more than “Scholar” or “Famous Poet”, and suited the man well. ‘James K Baxter - Friend 1926-72.’

*

Today the land of Jerusalem is green, the grass grows long and tough, and the earth knotted with stubborn tree roots who dig themselves immovable into the soil.

A thin muddy track leads towards Baxter’s simple grave, marked with white stone and framed by tufts of spindly grass. From here St Joseph’s Catholic Church is visible, its thin spire peeping through the taller trees. The man who danced ideas and stories into majestic form is described simply on his gravestone marked:‘Hemi / James Keir Baxter / i whānau 1926 / i mate 1972’

This is where Baxter’s body lies, buried, restless heart lying still in the ‘civilised darkness’, watched over by the church he belonged to, his body a part of the earth he felt so strongly connected to.

A pair of sandals, old black pants

And leather coat — I must go, my friends,

Into the dark, the cold, the first beginning

Where the ribs of the ancestor are the rafters

Of a meeting house — windows broken

And the floor white with bird dung — in there

The ghosts gather who will instruct me

And when the river fog rises

Te ra rite tonu te Atua —

The sun who is like the Lord

Will warm my bones, and his arrows

Will pierce to the centre of the shapeless clay of the mind.

- Baxter, 'A Pair of Sandals', 1972

*

Weir’s close relationship and understanding for Baxter and his work has put him in the dual role of the bereaved and the foremost authority on everything Baxter related. Some people cope with grief by finding ways to let a memory gently diminish. Much of Weir’s life has been dedicated to keeping Baxter’s work alive and in print. An award-winning poet in his own right, Weir has edited a number of collections of Baxter’s poetry, penned essays, and this year released, James K Baxter: Complete Prose, an impressive four-volume collection.

At the physical and intellectual level, Baxter’s work endures. His influence is noticeable in generations of subsequent poets, not just in stylistic tics but in the ethos of those who choose to make outspoken politics material to their work. His poems continue to be taught in universities and schools across New Zealand. Literary promotion initiatives have seen his work, alongside Hone Tuwhare, sent as far afield as Nashville.

As for my current home in Wellington (‘City of flower-pots, canyon streets and trams, O serile whore of a thousand bureaucrats,’), Baxter’s words can be seen across from the Lambton Harbour jetty, where water dips over the stony letters, their meaning echoing across the wind-whipped water.

I saw the Māori Jesus

Walking on Wellington Harbour.

He wore blue dungarees,

His beard and hair were long.

His breath smelled of mussels and paraoa.

When he smiled it looked like the dawn.

When he broke wind the little fishes trembled.

When he frowned the ground shook.

When he laughed everybody got drunk.