Other Elsewheres: New Zealand at the Venice Biennale

Tamzen Dunn looks back on NZ's Venice run so far

New Zealand’s official platform at the Venice Biennale began in 2001, and our formal representation was arguably already overdue at this point. There had been anomalous instances of New Zealanders exhibiting at the Biennale: Frances Hodgkins (she was meant to be in a group show representing Britain, though this was never realised because of World War II), Kate Coolahan (works shown in 1972), Boyd Webb (as a part of Aperto 86), and later Simon Denny (in a curated show, 2013). Then there were the moments when it was like Federation had gone ahead, as New Zealanders showed works in various Australian exhibitions: Rosalie Gascoigne (1982), Richard Killeen (1990), and Daniel von Sturner (2007).

Our official representation covers every Biennale since 2001 with the exception of 2007, where an unofficial collateral show was selected by the Biennale’s Artistic Director. Here, the six completed official shows (2001; 2003; 2005; 2009; 2011; 2013), the one scheduled (2015), and the one unofficial show (2007) are examined as they might be representative of New Zealand. It is a short-long history of what the Biennale might say about us.

Not all the works are representational in any direct or deliberate way, yet in the end they are representative of New Zealand at the event. Regardless of the artist’s intention, their appearance at the New Zealand Pavilion and the way this makes the works play out on an international stage is inevitably tied to the country of origin.

2001

The first New Zealand Pavilion was at the 49th Biennale, a double exhibition with the overarching title of Bi-Polar, encompassing Divine Comedy by Peter Robinson and A Demure Portrait of the Artist Strip Searched by Jacqueline Fraser.

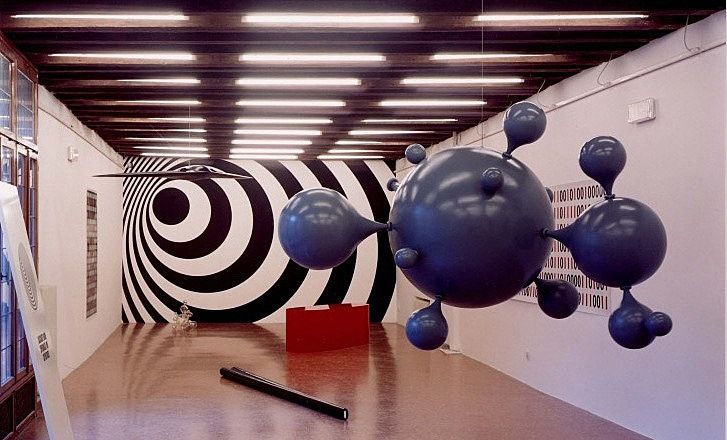

The works are both installations, but they take markedly different forms. Robinson’s work comprises sculptures and digital prints, based on a binary encoding of Dante’s work, and elements of Stephen Hawking’s theories and writings. The binary itself is an encryption of Dante’s Inferno: a digitised image of international (Western) thought and culture realised in a colour scheme which evokes Māori visual art . The work occupies an open space, centring on a suspended bulbous, amorphous form. It is sleek and minimal, recoding and contextualising its source elements, and rendering them into something different entirely.

Fraser’s work, on the other hand, is an intensely personal exploration, a mixed media assemblage of several textures and forms of person and of femininity. The work comprised texts and small wire sculptures representing female forms, shielded from the world by textiles taking the forms of dresses, shawls, veils: the ways in which a woman might be demure. These pieces were exhibited between large damask curtains, which echoed the softness and shapes of the works. The drapes formed a maze which had to be negotiated, meaning that in execution, the work mimicked the inaccessibility of inner states. The idea of the self is physically present, but it is hidden away.

Both artists share Ngāi Tahu descent: they identify with Māori and Pākehā heritage in a bicultural nation. The "bi-polarity" of the exhibition title further indicates this idea of separation, of twoness and togetherness, and their work is created in the context of these issues. The exhibition might be more richly read in terms of meaning made through binary oppositions.

The incorporation of binary encoding into Robinson’s work acts as a literal instance of such opposition: a visual metaphor of two different forces working together to create meaning. The two cultures and histories are realised in the same image, and while the Māori element may not be recognised by international audiences, the Dante similarly cannot be read by most people in the 21st century. They are both removed from context but part of a coherent whole.

The outward, open nature of Robinson’s show contrasts with the sheltered soft space of Fraser’s. His looks to possibilities: what might be (binary existing as zeroes and ones, nothings and potentials). Fraser’s is instead protective and demure, shielding the self. It is a felt interior, an intensely tactile space (almost womblike), creating a personal – rather than a public – experience.

The gendered split of the artists exhibiting is a further coming together of perceived points of difference. Their approaches to identity and existence, though different from each other, herald an impressive shift from the straightforward identity politicking of, say, Colin McCahon’s I Am (the solo male artist – a significant character in the canon of New Zealand art – here assuming the voice of God in his work). They look instead to something more universally applicable and experienced: Robinson contemplates existence, potential, nothingness and beginnings; Fraser reflects on personal life, incorporating the audience into a private space.

It could almost seem that the nation is – artistically, at least – ready to emerge from the navel-gazing which came before; that it might be secure enough to come forth asserting its existence and look beyond the person of the artist to the potential of the art.

2003

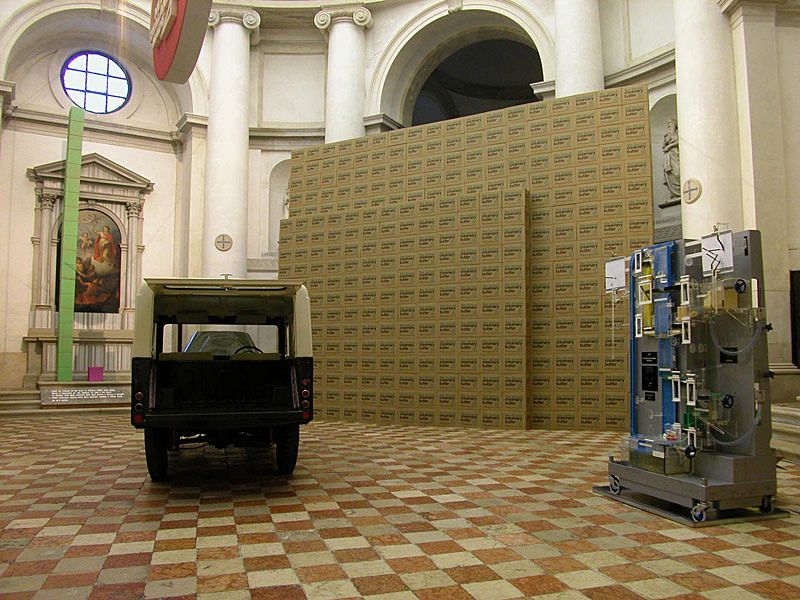

2003 saw a solo exhibition: This is the Trekka by Michael Stevenson. Trekka examines an earlier instance of interaction between New Zealand and Europe, before the Biennale, establishing a kind of ongoing camaraderie and cooperation, a fusion of the old world and the new. It is a local history with a view to globalisation: New Zealand’s lone, brief foray into car manufacture, a car built in Onehunga with parts imported from Czechoslovakia.

The work comprises a fully restored and functioning Trekka, a wall of butter boxes manufactured in New Zealand (and referencing the local dairy industry), and a Moniac (a huge, primitive computer designed for measuring a nation’s economy, designed by NZ economist Bill Phillips in the late 1940s).

The Trekka represents a kind of antihistory or anomaly. It is our only mass-produced vehicle: 3,000 were produced in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, several units were subsequently shipped to South Vietnam to serve as ambulances.

The exercise existed as an idealistic pursuit of nation, international relations and car-building in one, and proved ultimately (largely) fruitless. The car is here, fully restored and functional, a homage to nationalistic pride and initiative. It evidences the ambitions of an earlier New Zealand: that if we could make a car we would have proof of ourselves as a strong and functioning national economy (possibly paralleled to our ambitions of ‘making it’ in the global art market through exhibiting at Venice).

The work was well-received, but its deliberate trade show aesthetic was entirely at odds with the classical surrounds of La Maddalena, a mid-14th century church. The work acted as an affront to the building, neither incorporating nor responding to the space in which it existed (unlike Judy Millar’s work six years later in the same exhibition space). Like the car it represents, it seems an exercise in good intentions for little result. Yet in doing so, it actually became a telling instance of the (sometime) ineffectuality of the number eight wire, Kiwi ingenuity mentalities that we pride ourselves on and define ourselves by: we could build it, but they did not come.

2005

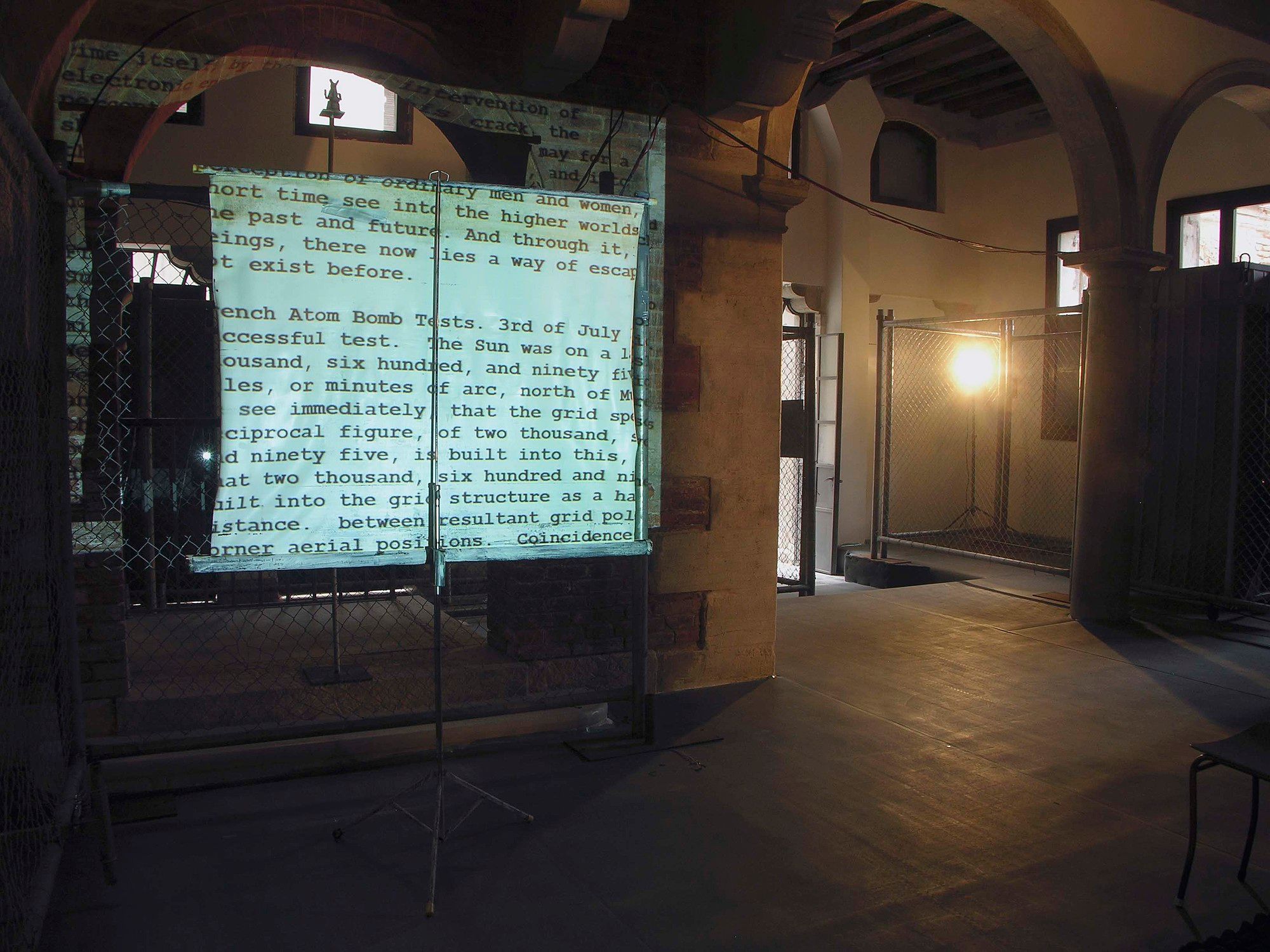

The anonymous collective et. al. (headed by Merilyn Tweedie) presented the fundamental practice at New Zealand’s third Pavilion. This is a complex work of computers, chairs, screens, and wire gates. The space gives the suggestion of a control room with an operation in progress, or the feeling of being in a bunker. It is a hostile space, a constant flow of information and accompanying noise incorporating austere mechanical forms, computer screens, projections, movement. It's an auditory affront too, with detached and unrecognisable sound recordings playing at random (among them a squawking parliamentary debate considering the appropriateness of et. al. as representatives at the Biennale).

the fundamental practice operates as a testing ground, a constant questioning experiment/experience which queries preconceived notions and fixed ideologies by creating new ones. The operation (it seems this more than an installation, per se) acts as a constant deluge of information, a confusing space of sensory overload. Between the noise (loud, indiscernible), the objects (large, mechanical), the smell (damp), the colour (matte grey), and the overall aesthetic (underground, under construction), the work took over the viewer’s space and senses, subjecting them to some hybridised form of military, scientific, and political systems.

et. al. look to challenge the orthodoxies we establish and accept: to move beyond a set of truths established by habit rather than experience, and toward something less definite. Thus the anonymity of the group, the flux and flexibility of the exhibition, the declining to comment on the(ir) work. The viewer is placed in a position of discovery, navigating systems which create new orthodoxies. They must make the meaning of the work in the challenging, complex space. And the meanings created are unclear. The work is a physical experience, and the negative response to the work came primarily from those who had only seen the work through photographs.

The enduring memory of the work in New Zealand is one of confusion and criticism, particularly among those who have not experienced it. The complaints levelled at the work of et. al. often err on the reductive. Instead of investigating aspects and potential meanings of the work which warranted their selection for the Biennale, Rapture (2004) was popularised as a ‘braying portaloo’(this title was later casually transposed to the Biennale installation). The then-Prime Minister and Minister of Arts Helen Clark, perhaps stung by crticism that went to the heart of her portfolio, turned on et. al. as a poor ambassador for the country. This wasn't just the view of politicians: Herald arts critic TJ McNamara’s seemingly dismissive critique read:

The award for making art out of the commonplace found object goes to et al, whose view of the world is of a place filled with mud-colored junk and squawking noise and where the most essential structure is a portaloo.

These criticisms elide the details which struck visitors first in 2005 - hours-long tapes of various sounds (including disembodied voices and morepork calls), and the work's bold political insurgency. The details which are fixated on (and thus fixed in the public memory of the work) are a singular noise, a non-specific shape. The work is reduced to these specifics and ridiculed for them.

It is like New Zealand’s response to Joel Shapiro’s struggle with his proposed North Carolina public sculpture being labelled ‘the headless Gumby’ (it was thought to resemble a cartoon character). The people with the power and influence to communicate about the work, lacking in either of art education, appreciation, actual experience or interest in attempting understanding, responded to a work by assimilating it with some non-art object they might better relate to. This, in turn becomes the public reading of the work: a self-fulfilling prophesy in which it doesn't not warrant further analysis because of its innate resemblance to this thing (even if that resemblance itself is often arbitrary or offensive).

et. al.’s outing was easily one of the more confrontational, contemporary pieces to have been exhibited by New Zealand at the Biennale. But it was definitely the most put-upon back home, and it was certainly the one after which there was no official representation. Despite its official recognition and appreciation at the event, the fundamental practice failed to register positively with the public and the press in New Zealand (the bitter irony is that contemporary art often obtains this wider interest only when public money is perceived as being invested in something which might be inflammatory or objectionable: the issue is unfolding again around Michael Parekowhai’s proposed ‘state house’ sculpture at the Queen’s Wharf).

2007

After the criticisms that surrounded the et. al. exhibition, Creative New Zealand was called on to defend the $500,000 spent financing the event. Declining to sponsor a Pavilion for the 2007 Biennale, Creative New Zealand opted instead to investigate other international events with a view to future participation (though this was largely interpreted as a step back after the controversies and public backlash surrounding the et. al. show).

Instead there was a self-initiated project, Aniwaniwa by Brett Graham (sculptor) and Rachel Rakena (video artist), selected by the Biennale’s Artistic Director Robert Storr from hundreds of submissions. Despite the lack of public support (and funding), it’s arguably the best instance of contemporary art, cultural heritage, and international concern to be shown by New Zealanders at the event.

The work is a series of pod-like sculptures, suspended from the ceiling, housing video screens. Mattresses span the corridor below the sculptures, reminiscent of sleeping arrangements in a marae. The screens show images of people and water, people in water, abstracted colours and shapes. There is no point of fixity in the images, no still point. The images are indeterminate in time and place.

An audio element is included in a Māori language soundtrack made by Whirimako Black, Deborah Wai Kapohe, and Paddy Free.

The work looks to the flooding of a town, Horahora, in 1947 to build a dam at Karapiro. Graham’s father was born in the town and here, submersion becomes a metaphor for loss (especially poignant considering the threat global warming posits for the Pacific Islands, and for Venice). However, there is also a potential for rebirth and the transferral of energies included: water makes power, power makes light, and light emulates water again.

The elements of New Zealand history and culture are incorporated seamlessly into this work: it never feels like an exhibition tactic or an afterthought to justify its national link. The work’s origin lies in the Waikato, but its implications are global. It shows the parallels between local and international history and present concerns: how all lands are islands in a world of rising waters. The work references a definite historic loss while alluding to a potential future one.

Aniwaniwa shows our ability to look beyond our own boundaries towards more common concerns and shared experiences. Personal, historical, and national concerns are fused within the work which – while specifically New Zealand in origin – speaks to global issues: the ebb and flow of history, memory, time, and water.

2009

Another double exhibition came in 2009, with works shown by Judy Millar (Giraffe-Bottle-Gun) and Francis Upritchard (Save Yourself).

Millar uses a digitalised process to distort and enlarge her painted canvases then prints them billboard-style: sleek and flattened, a kind of painting once-removed. The resulting canvases fill the exhibition space, responding to its curved walls and lofty ceiling of La Maddalena. Millar recontextualises her painting into another dimension (the two dimensions of the flattened printed surface, the three dimensions of the room), looking to its potentials and what painting might be in another context. It becomes an object set apart from its origin.

Upritchard similarly works with a distorted, illusionistic idea of space, separating her figure montages from their surrounds. She presents miniature figures in a state of reverie or reflection, removed from our space through their refusal to engage with it, doubly distanced from their surrounds through their proximity to large antique mirrors.

The interaction of these forms with the mirrors could assert an unsettling or alienating oddness in their surrounds – indeed, this downbeat reading could be the path of least resistance for both the artist and a viewer. But the concept of ecstasy comes from Ancient Greek: ek- (out) stasis (a stand), to do with the withdrawal of the soul from the body, to be outside oneself. The figures are in a state of ecstasy: infinitely happy, displaced from our world as the work is displaced from its environment. This removal from the physical space reinforces the reverie of their evident experience.

Both works are matters of scale (one large, one little), and of interactions with space and displacement. The artists are similarly distanced from their points of origin. Both are expatriates, an ongoing issue arising when considering inclusion at Venice as representative of New Zealand. Upritchard lives in London with her husband, while Millar had said she experiences a kind of forced displacement in pursuit of her work (“So I would stay home, if I could” she detailed in a 2010 interview).

The OE is seen as a rite of passage for many young New Zealanders, and exhibiting at the Biennale might represent a similar enterprise for artists. We can find and assert ourselves there while representing and remembering (though not explicitly referencing) our homeland.

Despite that displacement, there is still a connection with the point of origin: New Zealand. The works and artists are evidence of our diasporic communities, how we respond to the spaces where we find ourselves, though we remain aware of other elsewheres. We can belong in Venice while belonging to New Zealand.

2011

Michael Parekowhai exhibited the impressive On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer at the 2011 Biennale: a large installation comprising many parts in different places. The installation takes its name from a John Keats sonnet, which details a Spanish adventurer looking out over the Pacific, imagining the riches which might be found there. Parekowhai responded to Keats’ ‘He star’d at the Pacific’: “if they could see that far, they’d see us looking back at them.”

The work encompasses three pianos, two bronze bulls, a Kapa Haka figure, and two olive saplings (also in bronze). The central piece of the work is a carved 1926 Steinway, He Korero Purakau mo Te Awanui o Te Motu, Story of a New Zealand River: the culmination of a ten year project of dismantling, rebuilding, carving, and reconfiguring a performance piano.

The exhibition is an assemblage of objects, but more important is the music. New Zealand and European pieces were scheduled and performed at the piano, meaning it exists as the focal point of a fusion of European high culture and New Zealand art – specifically Māori art. The carved forms and red paint of the reworked Steinway are unmistakably Māori, the musical instrument/element steeped in European tradition and high culture. The form and function of the piano are unified, with neither taking precedence. Old and new are fused into something entirely unique and modern.

I wonder if the work could serve as a model for the nation: that the Steinway taken apart, remade, and reconfigured into something fusing aspects of two things, might be a design for what we could achieve. It’s rampant idealism, but here the respect paid to both heritages and the necessity of each contribution to the final piece serves as a sound example of bicultural practice.

Parekowhai represents the potential of New Zealand, what we might be able to achieve (given time, patience, assistance, a lot of undoing and a lot of work). Māori and Pākehā traditions both make significant contributions to this artwork and can form the fabric of wider society. The music they make together is certainly beautiful; what this work says about us as a nation is, maybe, that we should try.

2013

Our 2013 showing at the Venice Biennale was Bill Culbert’s Front Door Out Back: an inside work of assembled fluorescent tubes, repurposed domestic furniture, and milk and detergent bottles, and an outside work of glass flasks half-filled with water. The everyday objects are removed from their regular context and reimagined as an art installation. The work is meant to comment on purity and pollution.

Culbert’s inclusion as New Zealand’s representative at the Biennale is a bit bewildering. He was born here, and identifies as a New Zealander. But he left the country in 1957. His practice, though current, is hardly contemporary. While he is a high-profile artist, what he can contribute to a dialogue between New Zealand and Venice in 2013, what insights he might have into local life, culture, and contemporary practice, all can be called into question.

Culbert’s work seems to echo a lesser idea of New Zealand than has previously been exhibited at the Biennale. It elides cultural diversity and meaning, instead looking to ideas of domestic kitsch and the tropes of Kiwiana. Though the title and the incorporation of household furniture could be considered, this critique focusses primarily on the milk bottle form. This seems to be the most symbolic, the most recognisably New Zealand thing about his work. And aren’t we a little past that?

The work looks to a nation desperately in search for modern symbols of identity that it can fall back on. It is almost the art equivalent of the Kiwiburger jingle produced for McDonalds in 1991: an assemblage of trite aesthetic points and cultural practices so mundane they become meaningless (visitors might almost be told to ‘leave your jandals by the door’).

This work looks to a New Zealand which does not exist anymore, and is by a man who does not live here anymore. It is not the only instance of an exhibition with a camp or kitschy look at ourselves (the Trekka showed a severely dated, unsuccessful instance of New Zealand innovation), nor is it the only instance of an artist living abroad (Millar and Upritchard, and Simon Denny, do not reside in New Zealand). Though Culbert’s work is visually compelling (to an extent), there is a definite feel of cultural inertia within it. It looks to a domicile, domestic nation, a people caught up in the nostalgia of imagining themselves the product of number-eight wire and know-how. What it says about New Zealand, now, is lamentably little.

2015

Last month, Simon Denny’s exhibition Secret Power opened at the Biennale. Denny is perhaps the most representative artist possible of New Zealand’s current social climate, right down to questions of value that are usually hard to translate otherwise. We can look to the country’s ‘rock star’ economy touted by the Prime Minister and the press, our desire for international relations, trade agreements, and attention (and the ability to secure them), and find these reflected in Denny’s work and successes.

Writing for Metro last year, Henry Oliver noted Denny’s international recognisability in 2014:

…according to Artfacts.net, a website that quantifies the attention artists receive at exhibitions and auctions, Denny is ranked 546 among all artists, living or dead. Number one is Andy Warhol. Number two, Pablo Picasso.

No other New Zealand artist comes close to this ranking. And, as of April 2015, Denny is now ranked 500 in the world. It is an unprecedented display of international public awareness around an artist from Auckland.

Denny was invited to exhibit in a curated show at the Biennale in 2013. Currently, he has a solo show at MoMA PS1 running from April through to September (2015). He is establishing his brand (quite self-consciously) as a formidable player on the international art scene.

Denny’s work looks to modern media and publicising in an engaging and accessible aesthetic. More so than previous Venice shows, he is heavily influenced by graphic design and rooted in the language and look of advertising. He questions new media, understands marketing, and is an indomitable force (by our standards, at least) on the world stage. His work is concrete, present, unavoidable and clear.

So it seems there is no one better to represent our nation as it stands. Denny desires, warrants, and has international attention and profile. To talk about it in those aspiration terms New Zealanders tend to, he is our best shot at the big time. In saying that, I wonder and worry what audiences will take Denny as saying about New Zealand in this international context. Secret Power was researched in collaboration with Nicky Hager (and named for his 1996 book about NZ’s role in the international spy network). The work is compelling, large-scale, engaging, and grand. But whether or not the consensus by the end of the festival is that it’s good remains to be seen.

(Though, maybe it’s just that I preferred when his materials list included things like ‘static electricity’.)

From Denny backward, our involvements in the Biennale assert the importance of space and of sound, the incorporation of history, culture, and memory into the works. They also reflect and respond to the trace elements of Kiwiana in our system, and can indicate (or react to) the perversity of the public. We are always on the outside looking in: the artists to the nation, the public to the art, the New Zealand art scene to wider world movements. It is a privileged position and perspective to have, and a compelling narrative is developing from it: a narrative of development, divergence, dissent, and discovery; a narrative which will continue to grow, provided there aren’t too many portaloos along the way.