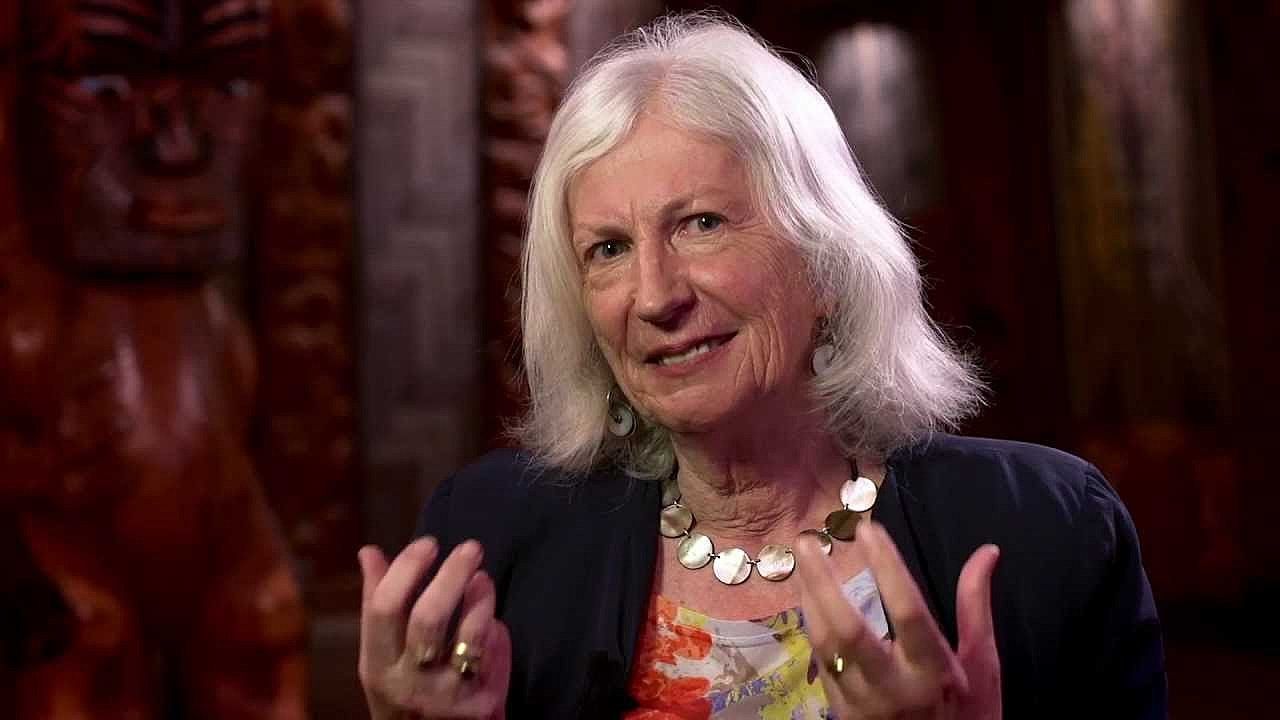

One Strange People, And Another: Dame Anne Salmond on Tears of Rangi

David Hall speaks to Dame Anne Salmond about her new book

David Hall talks to Professor Dame Anne Salmond about her ambitious and extraordinary new book, Tears of Rangi, and the pressing societal questions it causes us to ask in 2017.

He iwi kē, he iwi kē, titiro atu, titiro mai!

One strange people, and another, looking at each other!

—a haka by Merimeri Penfold.

There was a time, according to Mohi Turei, when the word māori meant ordinary, usual, normal, everyday. It meant “not of te pō”, not of the extraordinary realm of darkness and ancestors. That changed when Europeans arrived. Then was there another people to distinguish from one’s own: ngā Pākehā, unusual in their way, yet also inhabitants of te ao mārama, the everyday world of light and phenomena. Thus, what was once ordinary, (māori) became distinctive(Māori). A people, but also a cosmology, a sense of reality, and a way of life. Eventually, English words intervened, for the ordinary as for many other things. Māori were dispossessed as Pākehā, both demographically and imaginatively, established themselves as the new normal. The ordinary was confiscated by the other.

Tears of Rangirefers to rain, but, more urgently, to the grief and agony of separation – to the original severance of day from night, light from dark, Ranginui from Papatuānuku. This is the invocation of what is surely Professor Dame Anne Salmond’s masterwork, which brings together the strands of her life’s labours: her anthropological insights, her historical consciousness, and her efforts to influence – not only interpret – the tributaries of history as an environmentalist and public figure.

But this isn’t, barely, about division. Her subtitle, Experiments Across Worlds, emphasises the complementary dynamic: of engagement, of encounter, of bridging gaps through tears, words, gifts. The book not only describes such experiments, it is itself such an experiment.

Like raranga, it weaves together many threads: te ao Māori and te ao Pākehā, te reo and English, past, present and future. It splits and splices the happenings of Aotearoa New Zealand, showing how history shapes our present, how the present shapes our understandings (and our misunderstandings) of history, and how our future is shaped by the way we reconcile these myths and realities.

In this, the anthropologist is not only observer but participant. Quite properly, she is situated within the text as indeed she is situated within Aotearoa New Zealand, a member of the island society that she sets out to describe. Her sketches of history are guided explicitly by her sense of significance, of human relevance. We are left in no doubt where she stands on issues like water quality, gender equality and climate change (in case any reader didn’t already know) yet this empowers us to read her accordingly. There is no crypto-normativity, no ulterior agenda, because her commitments are laid out on the table for all to see. Nor is there any special pleading or brow-beating: just a poignant telling of the webs of thought that governed, and continue to govern, the messy interminglings of colonial and indigenous lives; that create miscomprehensions, mistranslations and mistakes, but also wilful wrongs and needless injuries. This is anthropology and history in its therapeutic mode, talking us down from the window ledge of our grander delusions and self-pretensions.

I visited Anne in her office at the University of Auckland. (This interview was lightly edited for readability.)

—o—

David Hall: I thought we'd begin with the subtitle to your book, "Experiments Across Worlds". What do you mean here by “world”?

Anne Salmond: It's easy to misunderstand that. When people hear about worlds, the image they have is probably a monolith, or planets banging into each other. But I'm thinking of ‘ao’ – so te ao Māori, te ao Pākehā, te ao tawhito. It's a dimension of reality, you might say, not as you would say it in English which is bounded, isolate, a thing-in-itself with boundaries around it. I'm talking about ways of being, ways of existing, which have assumptions about reality built into them.

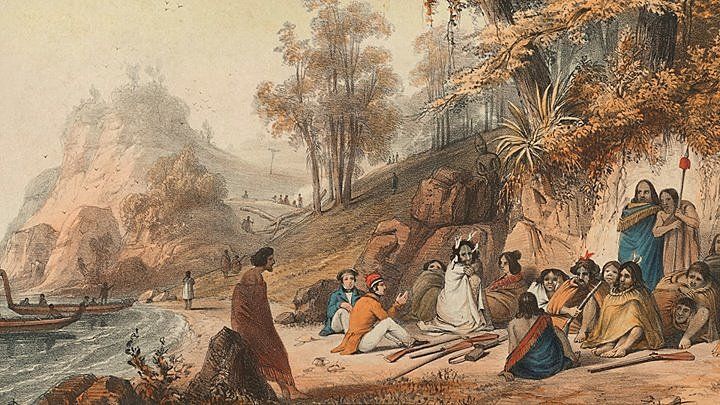

The proposition [of the book] is that rather than having one world with many views of it, we have – as indeed you do have in Māori and many Pacific languages – multiple dimensions of reality; and that what is real can change. In the first part of the book I was exploring this through a fine-grained exploration of the exchanges amongst particular people who were trying to make sense of each other, testing each other's worlds, trying to figure out how to live with one another. Like Hongi Hika going to Cambridge in England [from 1819–1821] to help write the first grammar of Māori and ending up meeting King George IV. He had a good look at English society at that time, but his attitude was, ‘Yes – very fascinating but not for me!’

Then, on the other hand, there’s the missionary Thomas Kendall who, when he starts to learn te reo, his views of the world get fundamentally disrupted. He starts thinking that Māori philosophy is the most sublime thing he's ever come across. There he is supposed to be converting these people to Christian beliefs – yet he experiences almost a reverse conversion.

If you think about this concept of te ao, you can be in one dimension of reality then, almost in a breath, flip over to another. You can be in te ao mārama, the everyday world of life and phenomena, the things you can see and feel with your senses. But then you might slip into te pō, into this other dimension which is dark, invisible and full of ancestors. Matakite – people with eyes that can see – have access to that kind of reality.

But then there are people like Samuel Marsden and Henry Williams who don't have these fundamental doubts. They're curious, they're interested, but, for them, their world is the best of all possible worlds; and the best thing is for everyone else to join them in it, to share their assumptions about what matters, about what is good. It's what our daughter [the anthropologist Amiria Salmond] would call a ‘mono-ontology’: there can only be one world. No self-doubt. No open windows. No way for the worlds of others to impinge. A world that’s somehow impervious. It’s also been a ruling assumption that's caused a huge amount of harm and damage in New Zealand, and limited our options.

DH: So the barriers between these worlds aren't strictly language barriers?

AS: No – not really. If you think about this concept of te ao, you can be in one dimension of reality then, almost in a breath, flip over to another. You can be in te ao mārama, the everyday world of life and phenomena, the things you can see and feel with your senses. But then you might slip into te pō, into this other dimension which is dark, invisible and full of ancestors. Matakite – people with eyes that can see – have access to that kind of reality. If that's the way you understand life, you operate differently. I know that because I've lived very close to people who lived that way – my mentor and kaumatua Eruera Stirling was like that.

But when we're talking about te ao Māori, we're not just talking about all Māori people either, because some Māori people today are not that tuned into these philosophies. It’s not something you get out of your genes, but a way of being. Whakapapa gives you the entitlement to participate in it – and as I’ve long argued, whakapapa is quite inclusive; there's all sorts of ways of bringing people in. But that doesn't necessarily mean you're going to find yourself in there all the same.

DH: So how are we to conceive of the commonalities between worlds? Isn’t there a temptation to go too far and say that we’re referring to the same thing?

AS: You'll notice that I never talk about commonalities. I talk about resonance. There's a kind of echo, but it's not exactly the same thing. For example, the idea of the Whanganui River being a legal entity in its own right is so interesting because, in one way, it makes sense, but if you really explore what Te Awa Tupua – the Whanganui River Act – is all about, a tupua is not a person. A tupua is a being from te pō, from the ancestral dimension. Tupua are generally much more powerful than people, so you have to treat them with care and respect. So, to give the Whanganui River Te Awa Tupua – the river that is tupua – the rights of a person is, in a way, to diminish it. Because in the old days it wasn't people who were guardians of rivers, it was more the other way around. The taniwha were the guardians of people.

So we can delve more deeply and come up with even better frameworks, better than this attitude that all this water is heading out to sea, just going to waste, so we might as well put it in an irrigator. But the problem with these attitudes is that they're actually not working. They're failing us. They're non-adaptive. They're leading us to do things that are self-destructive in the short run as well as the long run. That's why experiments are good because we can try something else.

DH: Another thing that struck me was that, even within the European world, there are many worlds. For example, the distinction between those European philosophers who thought in terms of a mechanistic universal rationality, or those who thought in terms of systems. Or the contrary advice given to Captain James Cook: the ‘Hints’ from the Royal Society to exercise non-violence and respect the rights of first peoples in contrast to the secret instructions from the Admiralty to ‘take possession’ of land on behalf of the King. There is this pluralism within the European world...

AS: And the pluralism of te ao Māori also. One of the biggest traps to fall into is to oversimplify. It's probably this habit of mind that there can only be one reality to test things against and therefore only one truth. Philosophically, that position can foreclose possibilities that might work better.

People take for granted many elements of the scientific project, and yet as it is currently constituted, its deepest assumptions are basically mythological. I try to tease this out in discussing The Great Chain of Being, where ideas of the Genesis play into ideas of resource management and ecosystem services; this belief that humans are in control of the cosmos, that if we stuff it up, we can fix it, because we are here to subdue the Earth.

The people who don't want to deal with the climate, they're also the people who want to close down the humanities and the social sciences. It's not handy to have people who are looking at those things closely and with a critical eye, because it interferes with power projects.

There's a paradox where modern science retains this infrastructure that is based on dead science. It includes all of these assumed dichotomies between subject/object, mind/matter, nature/culture, which have been dispelled by the findings of contemporary science itself. All these binaries just get in the road of thinking intelligently. They’re not working well when we're trying to tackle things like climate change or biodiversity losses, because this involves complex, related networks and systems where everything is linked together.

DH: So why does one view win out? These ideas about interconnectedness, or the need for consent from first peoples, were around for a long time. You know, occasionally this question is raised as to whether we can judge the colonisers because that was just their worldview and they didn't know any better. But when we look carefully, we see that they did know better, that they always had access to these other ways of thinking. It’s just historically inaccurate to even raise the question. So why did history end up the way that it ended up?

AS: Well, I can't give you any slick answer because that's probably the great question of our times! Obviously it has a lot to do with the will to power. If you are somebody who likes power, then hierarchical models, models based on control, have an appeal. Even the view that prevailed in cartography, ‘the eye of God’ approach, where you are standing above an abstracted reality and you are gridding it, measuring it, emptying it out of much of the phenomenal richness that is there. It's the same for Linnaean taxonomy and other sciences where you abstract and reify at the same time. But this forecloses other possibilities for understanding what's going on and how things are working.

I get incredibly frustrated at climate change conferences, for example, where climate scientists are talking about anthropogenic impacts as if somehow that's outside of the box. It’s unanalysed or only very crudely examined. Yet these so-called anthropogenic impacts are there right down to the molecular level. So if you actually want to do something about climate change, you've got to understand people as well as what's going on the atmosphere. Yet the people who don't want to deal with the climate, they're also the people who want to close down the humanities and the social sciences. It's not handy to have people who are looking at those things closely and with a critical eye, because it interferes with power projects.

DH: This points to a question I was saving for the end, to do with what Pākehā need to relinquish or surrender. Because this is often the source of the problem – this reluctance to yield, even when it's one's interest to yield.

AS: Exactly: the reluctance to yield and the will to power. One of the things that's interesting about relational philosophies is that the quality of the relationship comes into very stark relief. You're always looking to see if the relationship is balanced or not: who is giving, who is taking, where is the balance in the relationship? I had to learn that because if you want to have long-term relationships with people who think in Māori ways, if you don't follow those rules of reciprocity, the relationship dies. You find yourself stranded. People don't necessarily say anything. It's not necessarily hostile, but it dies. It's also true in thinking about rivers. If you keep taking and you never, ever, give back any care or thought, then the relationship snaps. If you want to end up really lonely in the world, you just extract and take.

Yet we have a very extractive set of philosophies at the moment. One of the things that's so self-destructive about neoliberalism is that it’s about what I get, what I extract, not about the quality of relationships with other people, or with other beings, or with the world in general. We end up with people who think life is completely futile and kill themselves; so many of our children are doing that. Societies that don't work: dysfunctional, fractured, unhappy communities. People who are taught to mistrust everybody else.

DH: And insofar as we do have reciprocal arrangements – say through the Treaty process – these are skewed by what counts as reciprocity. Pākehā give back money and assume that a slate is wiped clean, whereas, I gather, in te ao Māori, there is a much richer conception of what reciprocity would entail, including non-monetary value.

AS: It's really interesting if you think about tino rangatiratanga, that concept in the Treaty. There's a man called Te Rangi-kaheke who attempted to instruct Sir George Grey on how to be a good governor. He saw himself as Grey's mentor. He wrote a beautiful manuscript on rangatiratanga and one of the key things was manaakitanga: giving mana to others. It's hospitality, it's help, it's a generosity of spirit – that's how mana is built. It's not by taking, it's by giving, actually. But at the same time, if someone else is out there taking and taking and taking, there are restraints on that. Someone who does that usually gets short thrift: they get excluded or dropped. Someone who is regarded as a taurekareka (slave or scoundrel). Someone who has no grace, no human warmth – that's a really sad thing to be.

If you take something from somebody else's container, then you're nicking something of theirs. In a more relational mode, though, it's all about the quality of the relationship. If you start taking stuff and you never give anything back, if put your name all over it and take all the royalties, then of course it's appropriation and, actually, really bad behaviour.

The idea is that a relationship is about giving mana to others. So when we treat welfare beneficiaries as though they're dogs in the street, when our first thought is ‘When did they last rip off the system?’, it’s so incredibly ungenerous and uncaring. Taking people who are down and giving them a good kick. But you reap what you sow, you get that back. You get a society where people think that's the way you've got to be. I'll dish it back to you – and people do. Then you wonder why there's so much violence and abuse going on... This is why it's good to think of alternatives, because we need some. Life can be a lot nicer, happier and prosperous in the real sense.

DH: A word that’s around a lot is decolonisation. I was wondering what you thought about where this fits with the idea of “experiments across worlds”.

AS: I think this is different. Decolonisation perseveres with the original framing of colonisation; it gives power to that. You're basically saying that this is something we need to deconstruct in order to do things differently. But you could just choose to do things differently. I work a bit with artists and I wonder whether someone like Lisa Reihana, whether she would see herself as a decolonising artist. I don't think so. I think she would probably see that she's taking things that she likes, or is interested in, from all the legacies available to her, and trying to do something new with them. It's not that the other way of doing things is wrong, perhaps, but it's like saying you’re non-Māori. As soon as you've got a negative in there, its opposite is getting a lot of power.

DH: What about the idea of cultural appropriation? I sense that some people would feel anxious about this idea of experimenting with other ideas, worried about stepping too far or doing something the wrong way. What are your thought on how to navigate with hybridised space?

AS: But this assumes the idea of a world or culture as a container. It's got boundaries and we need to police them. If you take something from somebody else's container, then you're nicking something of theirs. In a more relational mode, though, it's all about the quality of the relationship. If you start taking stuff and you never give anything back, if put your name all over it and take all the royalties, then of course it's appropriation and, actually, really bad behaviour. Within that philosophy, it's about the worst thing you could do.

Whereas, if you're genuine, if you maintain good friendships and you look after the people you work with, if their idea is theirs and you acknowledge this, if you honour [the relationship] and balance it and try to give back more than you take, it's a gift exchange.

That's what I love about New Zealand. It's small enough and intimate enough that heaps of relationships go across the lines. We've been talking te ao Māori, but quite a lot has rubbed off in a very unacknowledged way. The fact that so many people could see the river as a being, for example, that it wasn't particularly strange. Or the sense of humour: the way that people laugh in New Zealand. We've got a chance to get these relationships working well and, I think, in many cases, they do. In many more cases, though, still nothing like enough. Like your point about the Treaty process: here's six million dollars, now go away and shut up. But this isn't the point. Pākehā never even go to the Tribunal: they don't hear the stories, they don't even know what they're paying restitution for. The relationship is still denied, so I don't know how that fixes that.

Tears of Rangi: Experiments Across Worlds is available now from Auckland University Press.