One Job

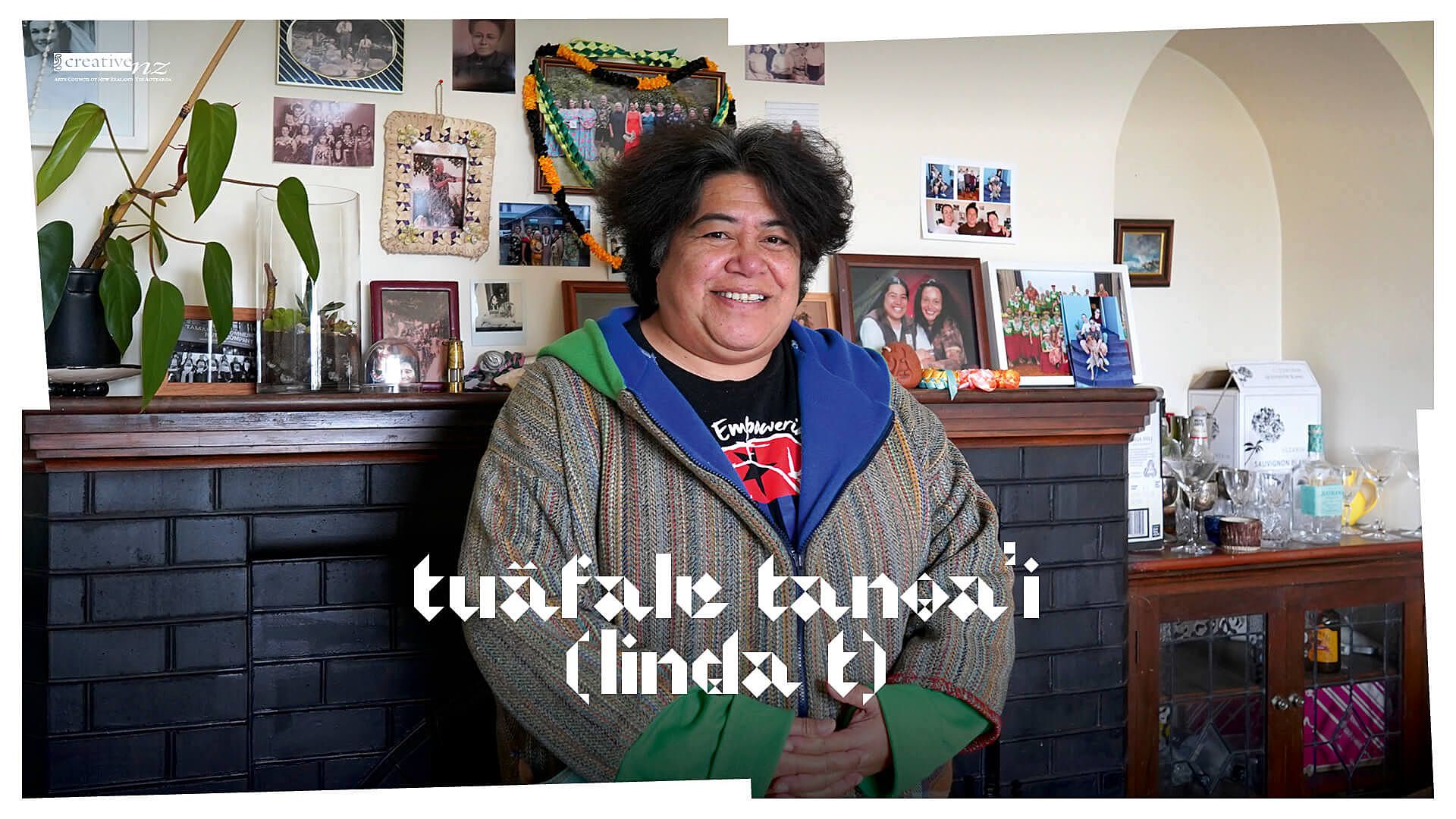

Artist, DJ, archivist and activist Tuāfale Tanoaʻi aka Linda T. has dedicated much of her time to recording the communities to which she belongs.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Documenting communities with recordable gadgets is one of many actions I engage with regularly. Creating music playlists and sharing them as a DJ is another adventure my time is immersed in. I’m a workaholic who is inspired by women creatives, and I intend to highlight parts of my journey, inner strength built through adversity and hardship. Thanks to the support network of friends that have assisted me in all the trials and tribulations that we’ve survived and often celebrated.

In the Groove – Clay Coworking, Anjuna. LIVE HIVE RESIDENCY, Goa, India 2020. Photo: LIVE HIVE

I’m a performance video installation artist who documents communities and I love to DJ and dance. My community art practice was born in inner-city Auckland, and I’ve been working it since 1976. I was raised in Kingsland with Sāmoan migrant parents who loved and served our extended families and our church communities.

My practice works to visibilise communities and people that are often misrepresented in mainstream society. This is done through generating a living archive of recorded interviews, photographs and sound recordings, which are then presented within a performative installation framework. The scope of the archive ranges from the political to personal,pertaining to Pacific, Māori and LGBTQI communities.

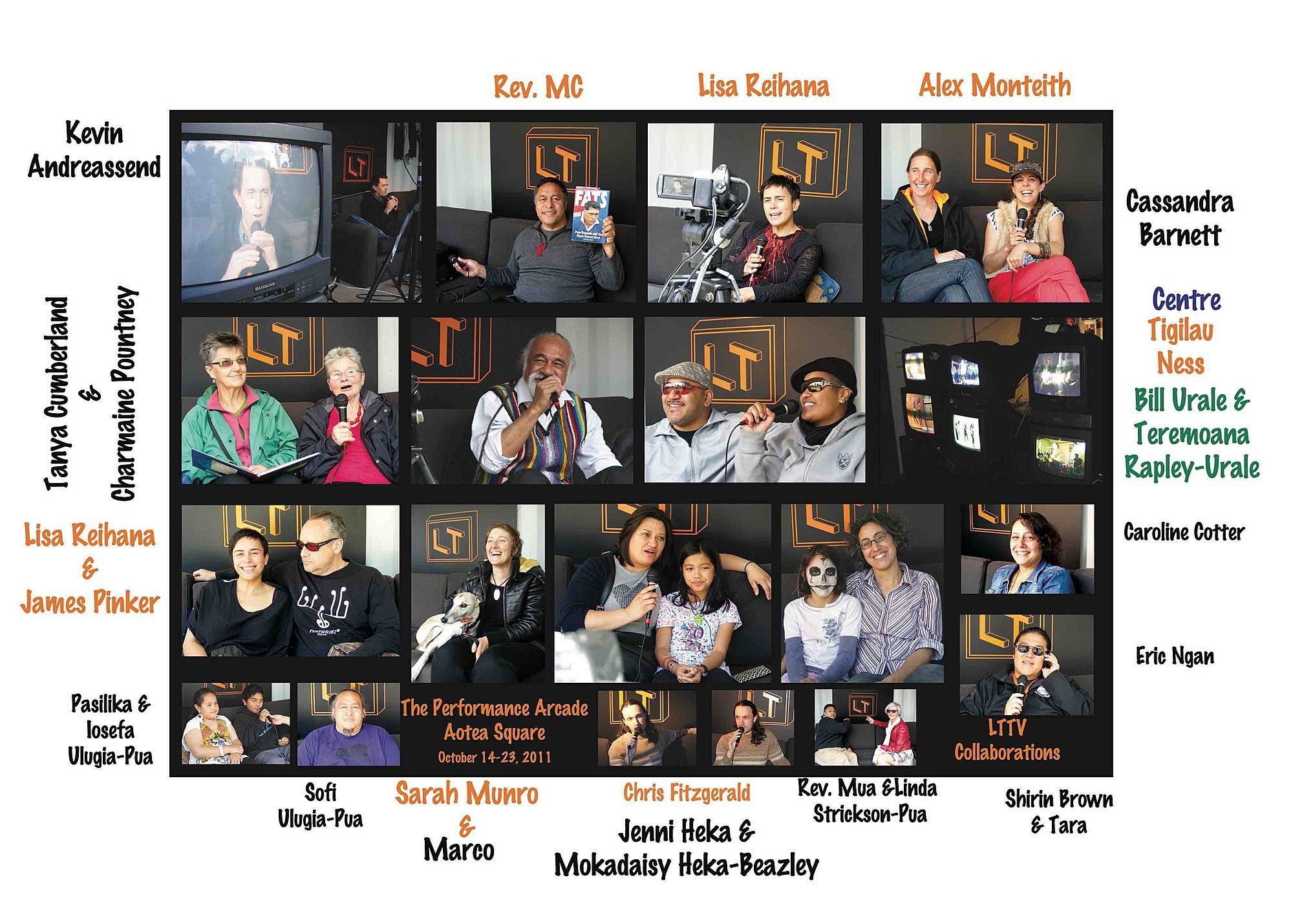

Performance Arcade, Linda T. TV featuring Rev MC, Rev. Mua Strickson-Pua, Aotea Square, Auckland, 2011. Photo: Naomi Singer

In 1968 I was lucky to be walking gayfully around one of my ancestral villages, called Lufilufi, on the island of Upolu, in the now Independent State of Sāmoa. The day I speak of is the day I became fully employed. I was five years of age, spoke fluent Sāmoan, and had recently my first haircut by the local village pool – yes there was a bowl involved and Mum seemed pleased at her efforts in front of a large audience, many would have been our extended family.

The day I speak of, I was hanging out with my cousins, uncles and brother, who were heading up to our plantation. I was the only girl child of my age, so followed them around like a shadow with a voice, “fa‘atali, e mu le sima, tina la‘u vae” – anyways, granddad was surrounded by a band of darker-skinned men, they were sitting, huddled together like Arthur and his merry men.

Granddad waves, calls me over, as I am running to keep up with my worker-elves relations who wouldn’t slow their pace for me. Granddad motions me to sit on his knee, the men make a gap for me to enter their realm. I see their faces and feel a little anxious; not frightened, just confused as to why they were wearing surprised – to me – looks. Granddad Tuani points away with a sweeping gesture, asking me in his softly spoken, deep baritone voice, “What do you see?” I reply, “Everything.” And I begin to name it all. He nods approvingly. Then tells me, “It’s yours, it’s ALL YOURS… to look after, to nurture, to protect, for our family, our village, our nation, our future.”

I nod and reply in our language, “OK Granddad.” I push myself off his knee and run off to catch up to the elves with their plantation tools. Granddad yells after me, so I pause, and he says, “It’s your ONLY JOB, tell your father.” I mention it to my dad, our father, when we return to New Zealand. He hugs me and I see tears roll down his cheeks while he smiles at me, shaking his head – I don’t think he liked his father-in-law that day.

Granddad Tuani with Tuāfale, on his knee, 1960s. Iafeta Tanoa‘i sitting on mum Ema’s lap. Aunty Laki and their cousin Fasiso‘o on the side. Photo: Artists’ archive

As I grew, I assumed that granddad gave many of his grandchildren or descendants the “it’s all yours” speech – and maybe countless Sāmoans or other Pacific people got the “it’s all yours, protect our world” JOB. According to the wise, we’ll receive the skills for the tasks that we are destined for.

In 1984 I attended an Outward Bound course. It was “designed to teach self-respect, initiative, compassion, tenacity and a genuine commitment to serving the community.” On arrival at Anakiwa we were placed in our watch groups of 14 – everyone was allocated a watch team after the initial welcome speech by the Watch Commander. If we weren’t happy in the selected grouping, we were to see the commander in his office. So there I was, waiting to explain why I refused to spend 21 days in a mixed watch of nine palagi men and three palagi women, all aged between 19 and 24.

I told him the extra stress of being with males 24/7 would be detrimental to my practical and personal experience. I didn’t want to deal with male sexism or homophobic views and especially all the white privilege that would surround me. So I was removed and placed in the all-female watch. Ten days in, I found out that everyone in the female watch had applied to be in the mixed watch – “because it would make the experience easier” was their main point.

According to the wise, we’ll receive the skills for the tasks that we are destined for.

We learnt about each other’s weaknesses and strengths and grew as a team. We had a top five: in all the activities that were scary, the top five would courage up and lead the way for others to follow, even if we were also scared. Lots of encouraging words were shared to get people through each activity: abseiling, the confidence course, climbing up the 100-step ladder for some of us who had a fear of heights. I nearly let go and could have fallen to my death, but a watch mate saw me pause and cling on to the ladder, not moving. I was tired and scared to go higher. Sean talked me up, encouraged me to refocus on the hand rungs, and kept saying “You’re nearly there, you can do it, keep going.” More watch mates joined her in vocally talking me up. I’d not done a flying fox ever, due to my being scared of heights. It was exhilarating and, yes, I did want to fly again.

Kayaking white water, I drowned and nearly died again. Seriously, I was stuck upside down in my kayak with bruised knees. I tell people that Superman turned up to save me, cos our Watch Instructor did do a miracle run, jump and hurl himself upstream, over rocks to get to me. We discussed the reality of the situation later that night, after the team analysis session. Yes, I was a goner, we both agreed. But we kept it between us cos some of the girls felt bad that they didn’t do their job, to keep my kayak off the rocks, as we were trained to.

A few days later, we forget about that feat because we nearly capsized the cutter, a huge old-as ship, when we got caught in a surprise storm in the Marlborough Sounds. I happened to be steering at the time, because it was my turn, anyway we all near drowned together! Heading to a random island to park up took hours of manoeuvring to anchor the ship safely. Getting a campfire going was another tedious task that took a long time. Boiling water for a much-needed cup of tea and hot dinner highlighted how much we all take electricity for granted (and dry matches)! Mountaineering, we managed to lose a day, due to differing perspectives – sticking to our newly learnt orienteering skills or taking a short-cut to get to our destination. We spent hours verbalising choices, finally decided to vote, and then I chose that everyone was to stay together! It was nearing sunset, so we set up camp and we set new rules before starting dinner. People were disciplined if rules were broken: they were simple and agreed to by all. I had a stick and used it to sting peoples’ legs.

“Racism is everywhere for us who are Pacifican or Indigenous or a person of colour.”

That night around the campfire changed everybody, through the personal stories that were shared, the explanations and examples about our lives. “We’re not all the same. We don’t all get the same education or choices!” “Racism is everywhere for us who are Pacifican or Indigenous or a person of colour.” It was a turning point for people, according to the end-of-course analysis and sharing session.

It was my dream to attend Outward Bound because I wanted to clock the fastest time in the half marathon. To prove to my ego and self that I was the fastest woman runner in our world. My Watch Instructor supported the notion. As it turned out, receiving heaps of letters from friends on our return, after being lost in the wilderness, was one of the highlights of being alive! Apparently the Anakiwa emergency squad were gearing up to come find us.

Much to our own credit we walked out of the bush under our own steam. Explained how one of our team fell ill, physically collapsed and we decided to make her a stretcher and took turns carrying her out. What’s a few miles amongst friends. Some of us even sang songs to keep our spirits up.

If I was a cat, I’d have used up three lives on that experience.

In my 30s I realised why I don’t drown. I’m a water tiger, according to Chinese Astrology. I’ve often dreamt that I drowned, but not a death drown of new beginnings, it’s a cleanse drown, to shake off the unnecessary baggage I carry.

As for the half marathon, I walked most of it. It was a life-changing decision that I made the un-sleep-able night before. Reading a letter by one of my favourite people and realising I had an important role to play in my communities, with my camera and with my DJ skills. Concluding that I wasn’t going to be the world-class runner, pro athlete that I assumed was my future. Even with a world-class medal-winning coach on offer – I hated his not-funny racist jokes, disliked the sexist crap that people felt was okay; I also disliked the food, that was huge, the food. My life was hard enough, with being allergic to onions of all kinds and having to navigate racism, sexism and lack-of-money-ism, without the words to articulate my distress. I felt betrayed, so I stopped running and walked the much-loved marathon – it was a funeral walk, to honour my new life plan.

My course experience had me in tears at the final evaluation session with our watch analysis, where everyone was to give each other critical assessments, with positive and negative points. This could be heart wrenching for some. People were brutally honest. But the team gave me verbal samples of my brilliance, no negative points – I was stunned and burst into tears – my family and friends would be proud of me.

*

How do we eradicate the ISMS? Racism, Capitalism, Sexism, Homophobia, anti-Queer, anti-LGBTQI-ism, eliminate slave and rape cultures? Pay equity – When? Now!

How do we grow understanding? Empathy?

How do we deconstruct our world and piece it back together so all our carbon relations get respected and live enjoyably, sharing all of our world’s assets?

Humans don’t need to be destroying everything, like we presently do. One percent of humans doesn’t need to be enjoying and encouraging the destruction of the lifestyles of the many.

Capitalism doesn’t have to be the foundation of our present human reality. Present world governments and policing support capitalism and all its destructive relations.

I’m not suggesting anarchy.

I’m suggesting Pacific Peace.

These are issues I think about, issues I address in various ways. It’s part and parcel of my ONLY JOB.

*

Spontaneous Intentionality, solo exhibition, The Physics Room, Christchurch, 2019, exhibition opening event. T. Tanoa‘i celebrating with some of the locals that womenised and Indigenised the screens. Photo: Jamie Hanton

Maya Angelou spoke of determination and delight in creating her work, and that “the achievement is delicious”. By 1976 she’d published her fifth book, had written two plays, a movie and a television production, and had a monthly article in Playgirl. It was Maya Angelou’s autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings that led me to enjoy books and reading. Previous to that, I had preferred comics and very short stories, like Witi Ihimaera’s Pounamu Pounamu.

In 2009, I completed an exegesis as part of a Master of Art and Design degree at Auckland University of Technology. It was called Storytelling as Koha: Consolidating Community Memories. The abstract reads:

This project will explore a fusion of Tangata Whenua and Pacific perspectives within a performance installation framework. I intend to juxtapose community narratives within a video art form. I will explore the recording and transmitting of indigenous stories and will create contemporary narratives linking the past to the present. Working within my communities, this project will investigate aspects of performance installation using live sets amid recordings of conversations and develop an interviewing practice. The performances are temporary and the devices ad-hoc.

This research project began as a way to rediscover stories that I had experienced in my past. It was intended to explore an installation practice using multimedia equipment that linked people, issues, places, and events with visibility, representation, difference and other. Storytelling as Koha project was also created to solidify my memories of past community events and to koha images back to the communities that I am a part of with conversations and interviews that rearticulate, renegotiate stereotypes and will indicate various characteristics of the multi-layered complexive works that I have engaged with during this thesis project.

The exegesis basically sums up the continued installation works I create and sustain. I’m inspired by female artists of many artistic disciplines, musical genres, sporting codes. Although obvious works are regularly created for exhibitions in galleries and other public arenas, pop-up shows are my favourite, for their spontaneity.

Master of Art and Design graduating show, 2009, AUT, Auckland. Photo: Artist’s archive

Performance Arcade, 2011, Aotea Square, Auckland

Spontaneous Intentionality, 2019, The Physics Room, Christchurch

From the Shore exhibition shoot, 2020, the Art House, Otago Polytech, Dunedin. Photo: Artist’s archive

From the Shore artists’ talk, participants pose in my exhibition space surrounded by seven out-of-shot screens, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, March 2021

*

Don’t ask me why I like art.

I don’t like art; I just think about it, engage with it everyday.

It helps me to build and complete works by engaging with different media.

It gives me methods to tell stories in a multitude of ways.

I don’t like art; I love it.

Don’t ask me why I like to tell stories.

I don’t like to tell stories; I just think about it everyday, in different ways.

To help create histories that link the past to the present.

To help to re-address colonial issues and to feed into decolonising minds.

I don’t like to tell stories; I love it.

Don’t ask me why I question western methodologies.

I don’t like it but I question western methodologies most days, in angry ways.

It enables me to address a ‘politics of difference and otherness’ (hooks, 1990).

It highlights imperialism, critiques notions of ‘identity for oppressed groups’ (hooks, 1990).

It forces me to look at my ancestral knowledge and my numerous roles in the present and future.

I don’t like to question western methodologies; it creates more work for me,

I dislike that intensely.

Don’t ask me why I have made the range of stories that I have.

Most of my recent works are snippets of my everyday.

They are moving image shorts of art openings, community poetry sessions, artist talks, artworks, private family gatherings, memorials to people who have had huge lives, lectures by people I admire, community housing events, artists analysing art exhibitions, book launchings, performance installation works and music videos.

I am creating my own version of reality television.

Don’t ask me why I use ‘koha’ as a work methodology.

It is part of a concept of giving, addresses notions of affordability and being accessible and exclusive.

It’s a way of life.

It addresses my alternative culture politics.

Don’t ask me why I use performance installation art.

I find it exciting and interactive.

It’s painful and pleasurable.

It is inclusive and exclusive.

For me, it is a realm that is ‘instantaneously planned spontaneity’. It’s unique and only happens once.

Don’t ask me why I don’t have a favourite movie.

I haven’t made it yet (2007).

But am finally working on it (2021).

*

First t-shirt design for a film promotion, 2020.

“If your films don’t heal, there’s no point in making them” (Merata Mita - in an interview for LTTV).

I am also a founding member of D.A.N.C.E. art club, an intergenerational artist collective born in 2008 at AUT University. Family members are Ahilapalapa Rands, Vaimaila Urale, Chris Fitzgerald and myself. Tuāfale Tanoa‘i aka Linda T. D.A.N.C.E. is an acronym for Distinguished All Night Community Entertainers and we have a huge list of actions and performances in communities locally, nationally and internationally.

Guinness World Record Attempt - Longest DJ Session, Artspace Aotearoa, 2014. It lasted 84 hours. This is an image from day 1.

Radio interviews with the elders of Rifle Range Old Folks Housing in Taupo. D.A.N.C.E. FM 106.7 Mobile Radio Show, The Erupt Festival, 2012.

Noho gathering of Māori and Pacific Island artists, All Goods Art Space, Avondale, Auckland, 2016.

My life as an artist with community practices has been and continues to be horrible financially, but hopeful, busy, exciting, lucky, fortunate, blessed, object-filled, entertaining, scary, gratitudinal, opportunistic, spontaneous, learning-filled, award-gifted, inspiring, heart-wrenching, loved – filled, to say the least.

To my granddad: our village, islands of Sāmoa and descendants of everything I saw in 1968 still exist, so I must be doing my job write

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Feature image: Edith Amituanai