One Dead Groove

In which I echo the sentiments of Duncan Greive and Gary Steel, two men considerably more learned and closer to the action than myself, who have blogged on Real Groove’s passing.

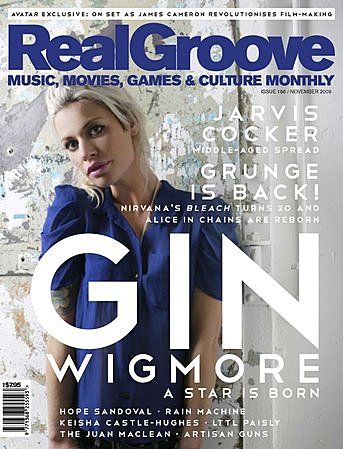

Real Groove will be gone as we know it on the cusp of its 18th birthday, flaming out at Issue 196 with Mr. Leonard Cohen’s grave visage on the cover (a Coolies feature, the product of a moderately boozy Thirsty Dog session with yours truly and two-thirds of the band, kicks for touch in there as well). The magazine will be, in part, folded into its little sibling, the fun, free weekly Groove Guide. While those involved at the coalface are absolutely right to view this as a merger and look optimistically at what the final result may be, it’s probably also fair to say that the magazine’s thick, delicious wedge of feature articles, interviews, oral histories, reviews, and opinion columns are gone as we know it.

Though the exact circumstances are fuzzy, I first became involved with RG in late 2006, when Duncan as then-editor contacted me to ask me to do the archival work on the mag’s exquisite 21st-anniversary commemoration of Flying Nun Records. The result was a through-the-past-quickly Central Library excursion, several days in which I got a sense of what the magazine had been and just how many times the format had leapt around: two-tone roots-rock reverence, scrawly student mag-lite Auckland rock coverage, a terrible dalliance with Korn and Limp Bizkit, and finally an awfully advanced matriculation of sorts.

I realise it’s popular to characterise print publications as being stagnant and resistant to change as they fall by the octet in 2010, but Real Groove kept evolving, varying and becoming more sophisticated to the last. The same publication put Paul Weller, Nas, and Die!Die!Die! on the cover in its final months, and I can think of no other place in the world where one magazine would embrace that sort of stylistic diversity. It asked, and expected, that people come along for the ride, and a number of people continued to do so to the end. Those that did didn’t just get lavish pieces on established and revered rock icons (see: Nick Cave, Neil Young, etc); they got confrontational, enthralling writing on genres basically disregarded by ‘serious’ music journalism. Articles by Duncan and Stevie Kaye on Southern rap and teenage third-wave emo got me dabbling my toes as a 20-year old neophyte where the likes of both Uncut and Stereogum turned their noses up, and I adamantly believe I’m the wiser and more interesting for it. And that’s ignoring the way the likes of So So Modern, The Brunettes, and The Mint Chicks got cover-story billing - Real Groove had a sort of messianic faith in what it chose to support that wasn’t always rewarded by the sort of sales that the product, or the subjects, deserved. But hey, it’s better than putting Muse or Tool on the cover.

So what went wrong? Absolutely not Sam Wicks, the tireless editor since the end of last year (Disclosure - I ran for this job myself, and the ownership quite rightly realised that the property sat better in experienced hands than those of a starry-eyed, stammering graduate). He oversaw a comprehensive re-formatting of the magazine that could have been jarring under anyone else’s stewardship, and had an eye for expanding his team’s stories from what could have been 1000 words of advertorial to 4000 words of majesty, purely by scoping out fresh angles and extra voices. The environment which defeated Real Groove was effectively bubbling under for the bulk of the decade, and Duncan aptly points out how it was shot by both sides - a dying industry (print) writing about a dying industry (music).

I’m not especially interested in engaging the commentary around this. Everything I’ve heard about David Cohen’s snide comments in the National Business Reviewreassures me I still don’t need a subscription to that bad baby, for example. But (trying to extricate myself from self-interest) I think this leaves us all a lot poorer.

We’re at a strange and possibly unprecedented time for music. The days when people bought selectively (30 bucks for a CD, hopefully not dropped lightly) and gave, say, critics and writers scrutiny before going ahead are gone. The only thing separating you from one of the most premier music archivists of his day is how good a deal you’ve got on your broadband connection, and while this has deflated a lot of the snobbery and exclusivity around music, the reification of the obscure, it’s also meant that we will never run out of the stuff again. We have more of it than we know what to do with, like so much ballast in our MP3 player. It’s fashionable wallpaper, divested of much beyond the silhouette imagery of an iPod advert. The sheer rate of consumption this enabled also meant the rate at which the machinery turned increased - Pitchfork scrabbles for relevance atop a set of prime aggregator blogs (Stereogum, Gorilla vs Bear), scrabbling for relevance atop a set of niche interest sites (bloghouse, chillwave, witchhouse, dancepunk, dubstep, tweepop, ad nauseum). The time for self-reflection or self-awareness has passed - it’s hard to evaluate the past month, week, or day when you’re trying to keep your head above water. A lot of these guys are ‘making it’, but it’s conditional on continuing to run on a treadmill of auditory information with no forseeable end. Discernment is death.

Where a good offline magazine could’ve filled the gap, and where I believe Real Groove was starting to, was in alleviating that infernal signal-to-noise ratio. Geographically and temporally removed, it spun its immediate disadvantage into an advantage, evaluating what had stood up in the neon sensory overload of the Internet’s night in the cold light of day. Some of what was left was garbage; some was gold - and hearing the take on either by RG’s writers was always fascinating (though reassuringly, they mostly stuck to the stuff they liked). Vile, fly-by-night poseurs and fakers were left to speak for themselves in judicious interviews - witness the fracas over Hussein Moses’ exchange with Dane Rumble in the magazine earlier this year, where the artist made a dick of himself in his own words and the writer simply provided the mortar for the bricks. Frequently, it railed iconoclastic against blog hegemony, NZ provincialism, the despicable reach-around that government funding of popular music had descended into. It’s a cliche, but the mag was old school. Every issue, there was at least something that raged against the downloading of the light.

Which is not to say it was all agitprop or anything: the writers bought superb knowledge from the outset, confidence and research to most of their interviews. Several of them wrote like absolute dreams. For a text-heavy periodical, by 2000s standards, it was always remarkably easy and fun to plough through.

That’s enough. It’s easy to wax nostalgic about things like this, but Real Groove exposed me to real writers, real situations and real opinions. It gave me some of the rarest and most amazing opportunities of my life (here and abroad) while improving me immeasurably as a writer (these things are still brutally relative, though). So here’s to Duncan, Sam, Stevie, Gary, Hussein, Gavin Bertram, Chris Cudby, Aaron Yap, Adele Hunter-Higgins, Courtney Sanders, and the rest of the coterie. You guys have left a deeply frustrating void, but it’s better than vanishing without a trace. Right?