On forgiveness

When someone in the spotlight does something unforgivable, how should we retroactively think about their artistic contributions? For that matter, where should we draw the line between forgivable and not?

Note that this article discusses acts of sexual and physical violence, homicide and anti-Semitism.

“It's behind me; it's an eight-year-old story. It keeps coming up like a rerun, but I've dealt with it and I've dealt with it responsibly and I've worked on myself for anything I am culpable for. All the necessary mea culpas have been made copious times, so for this question to keep coming up, it's kind of like ... I'm sorry they feel that way, but I've done what I need to do.”

— Mel Gibson in interview with Nick Holdsworth, The Hollywood Reporter, 5 July 2014

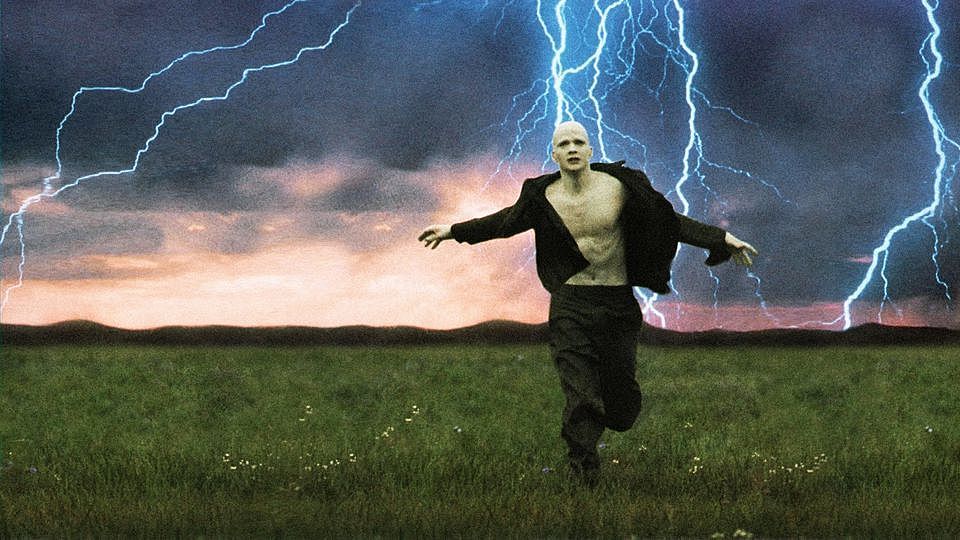

Hacksaw Ridge, a WWII-era film about a pacifist fighting impossible odds to save soldiers in a battle on Okinawa, releases locally in November. The poster says, simply: “From the director of Braveheart and The Passion Of The Christ.” It doesn’t use his name. Whoever approved it knows we know his name, yet hopes to avoid the neural association prompted by his name. Perhaps it’s been market tested, but even if it hasn’t, it makes gut-level sense: a film by the director of Braveheart and The Passion Of The Christ sells tickets. A film by Mel Gibson – a man still so notorious for his misdeeds that he was montaged back-to-back with Bill Cosby on the pilot of Mr. Robot as shorthand for the hypocrisy of society, a year after the above quote – doesn’t.

Another litmus test of Gibson’s notoriety: a convicted rapist prone to homophobic rants against journalists, who violently assaulted both a colleague and a motorist, showed up on the set of The Hangover Part II to play himself for comic relief. The crew of The Hangover Part II made a principled stand that they were unwilling to work with a member of the prospective cast. It wasn’t against Mike Tyson, ear-biter and accused wife-beater, but Gibson. Gibson was dropped from the film. Tyson featured prominently, as he did in the previous film. Why have the two been treated differently?

Before answering that question, it’s worth recapitulating Gibson’s crimes. He’s been accused of propagating homophobic stereotypes in Braveheart and anti-Semitic stereotypes in The Passion of the Christ. In 2006, he was arrested for a DUI; during the arrest he informed the (Jewish) arresting officer that “Jews are responsible for the all the wars in the world.” He received three months’ probation. In 2010, he was investigated for domestic violence against his then-wife, Oksana Grigorieva, and eventually pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor battery charge. During the furore, tapes emerged of a furious Gibson ranting in ways that could charitably described as hateful and less charitably described as wildly racist.

When a celebrity makes such public and egregious mistakes, a certain ritual is expected. It’s sometimes called the forgiveness tour. Mike Tyson did it repeatedly, even playing his ear-biting incident against Evander Holyfield for laughs and profit in a Foot Locker commercial. This plays better to some than others: Tyson was barred from entering New Zealand in 2012 to perform his one-man show. Antipodean rebuffs notwithstanding, Tyson’s public rehabilitation has indisputably been swifter than Gibson’s.

“I’ve done a lot of work on myself these last 10 years. I’ve deliberately kept a low profile. I didn’t want to just do the celebrity rehab thing for two weeks, declare myself cured and then screw up again. I think the best way somebody can show they’re sorry is to fix themselves and that’s what I’ve been doing and I’m just happy to be here.” - Mel Gibson (from an interview by Mike Fleming Jr), Deadline, 6 September 2016

Forgiveness requires the public to believe in the contrition of the subject. Take the discussion around Nate Parker, director of Sundance 2016 sensation The Birth of a Nation, who in 1999 was charged with rape along with his friend (and co-writer) Jean Celestin during his time at Penn State. Parker was acquitted, but Celestin was convicted of sexual assault. This information wasn’t news, but exploded publically in August when Variety published an interview with the victim’s brother, who argued that with a growing understanding of what constitutes rape, Parker would be found guilty today. The victim wasn’t interviewed: she had committed suicide four years prior.

What’s the correct response – the moral response? Should Parker’s film be boycotted? Should it be unreleased, despite the fact that it reportedly shines an unforgiving light on the messy heart of America’s racial history? Should every story about the film address the rape? Should Parker be allowed to make other films? Should Parker’s condemnation be more severe because of his choice to support Celestin despite his conviction? What, precisely, can either do to be forgiven, if anything? (One friend suggested that if the victim had not forgiven the accused, that they would not forgive him. This implies, of course, that Parker can never be forgiven.) And how is this complicated in show business, when the performance of contrition by a skilled actor may be impossible to distinguish from actual contrition?

Contrition – the act of admitting to wrongdoing, expressing remorse for that wrong-doing and apologising to those to whom wrong has been done – is a key factor in determining who we do and do not forgive. A lack of contrition (his own and his family’s) elevated Stanford student Brock Turner from one of the hundreds of thousands who have assaulted women to “the Stanford rapist”, one whose legal punishment has been and will most likely forever be seen as insufficient in proportion to his crimes. To even give voice to the possibility that Turner’s public opprobrium is disproportionate to his crimes – certainly when compared to others who have committed the same crime – is perhaps an unforgivable crime in and of itself. Certainly, it seems irresponsible to give voice to it without giving equal voice to his victim: on the off chance you haven’t read it, her victim statement is unflinchingly powerful and necessary reading. It may also give pause to consider what happens to victims who are less eloquent or willing to publicly face their accuser, and whose attackers fit less comfortably into a zeitgeist that allows for unequivocal outrage.

Contrition may be a precondition for forgiveness, but it by no means guarantees clemency. In my polling of cinephiles on what filmmakers they could not forgive, one name that kept coming up is Victor Salva. Some may not recognize the name, but might have seen Jeepers Creepers or Powder. Both films were made after his 1988 conviction for molesting a boy while directing Clownhouse. Salva was 29; the boy was 12. A 2006 LA Times interview contends that he has done his jail time, made amends as best he can, and deserves a second chance. Certainly he’s found no shortage of patrons, Francis Ford Coppola (producer of Jeepers Creepers) being the most notable. And yet I can’t bring myself to watch a Salva film, in part because of his crimes and in part because his post-conviction work arguably fetishizes teenage male bodies. I’m not alone. His public humiliation continues unabated, with movie news sites roundly condemning him, and casting services in Canada pulling a casting notice for Jeepers Creepers 3 after discovering the director’s past. (During the editorial process of this article, the author of the first linked piece stepped down as Editor-In-Chief of Birth.Movies.Death after being accused of sexual assault. It remains to be seen how his public humiliation will play out.)

Should Salva be forgiven? Should he have been forgiven if he made different movies? If he was forgiven, but not allowed to make movies, would that constitute forgiveness (clearly not)? And if we don’t allow forgiveness for certain types of offenses, how do we hope to re-integrate the guilty into society?

It may seem that I’m driving towards an answer, a simple calculus that tells us when to forgive. It’s quite the opposite. I find these questions deeply difficult and horrifically self-incriminating. A quick look at the shelf: oh, there’s Repulsion, by statutory rapist Roman Polanski (he was 43, she was 13. Why is that less offensive to me than Salva?). Look, there’s Pulp Fiction, co-written by Roger Avary, who killed two people in a drunk-driving accident (but I don’t have anything by Avary after the accident. Of course, he hasn’t made anything since the accident). I’ve also got Apocalypse Now, which features completely gratuitous animal slaughter. I haven’t watched Near Dark yet. I hear it’s great. The writer, Eric Red, drove his truck into a crowded bar and killed two people before attempting suicide with a broken shard of glass. One cinephile I know refuses to support Red’s efforts because of this. I’ll get around to Near Dark at some point.

I probably own 15 Woody Allen movies. Manhattan used to reliably rank in my top ten films of all time. Now, watching Allen seduce an underage Mariel Hemingway on-screen feels less like an interesting dramatic choice than a confession of private desires, particularly after Hemingway’s revelations last year regarding off-camera seduction attempts at a barely legal age. It’s still a great film, if you’re willing to put that aside, and if an ethically compromised film can be considered nonetheless great. Allen’s latest, Café Society, recently opened in New Zealand, on the back of a wave of fresh molestation accusations and tone-deaf denials. Allen is distinguished on this list by his denial of allegations (and, by extension, his lack of contrition). His defenders cling to the fact that he has not been prosecuted for any of his accused crimes. Of course, it’s not that simple. I saw Café Society anyway.

My relationship with some of these films is more complicated than others, but they’re on my shelves, a tacit endorsement. Does that mean I forgive their creators? Or do I merely quell my distaste because I approve of their cinematic works, whereas I refuse to give any quarter to Salva?

And if you choose to condemn me, are you prepared to thoroughly audit your own entertainment libraries? Maybe you are. Maybe you’ve already purged your DVD collection or hard-drive of all of the above, and of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off because Jeffrey Jones was a paedophile. Maybe you’ve thrown out Phil Spector, 2Pac, Ike Turner, Leadbelly, James Brown and Peter, Paul and Mary. (That’s not sarcasm. Peter Yarrow did prison time for taking improper liberties with a 14-year old girl). Maybe you’ve found a satisfying answer to the question of whether it’s responsible to give your money to someone you find morally problematic (but whose art you enjoy), and have fossicked through the decision tree for everything you own – are they living or dead? How bad was the crime? Do I believe their accuser? Does it not count if I deny them money and download it illegally?

I haven’t. It happens that I don’t own any Gibson-directed movies (out of disinterest rather than principle), but I saw Blood Father last month. As an ex-con who attempts to save his daughter from the long arm of Mexican drug cartels, Gibson plays a non-heroic martyr. It’s an act that could easily be seen as a surrogate for public contrition, were his obsession with martyrdom and self-destruction on screen not so thoroughly documented for many decades preceding his public indiscretions. The film itself is a satisfying no-frills thriller, the sort of thing that feels like it would have been ten-a-penny in the 70s but plays as a pleasing throwback now with few concessions to modernity and none to post-modernity. I recommend it. If, of course, you’re okay giving money to a Mel Gibson film.

What I’m struggling to put a finger on is why I’m okay with Gibson’s films, but found an ostensibly more innocuous film far more troubling. The First Monday in May is a documentary of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual fashion-related exhibition. The first designer to prominently feature on-screen in the preparation of the China-themed exhibit is John Galliano. I don’t keep up with fashion, and an obscure reference to mistakes he had made initially slipped past me. It was only after the fact that niggling curiosity led me to discover the vile anti-Semitic rant that had got him dropped by Dior and made him a pariah for a few years. It would appear that his public rehabilitation is underway, and it’s hard to not feel that one of the aims of The First Monday in May is to politely reconstruct Galliano’s public identity, not as anti-Semite but deservedly celebrated designer who should be honoured in the present.

The First Monday in May prominently features Anna Wintour, a longtime friend of Galliano, who’s been on a mission to rehabilitate his public standing for years (check out the ‘Comeback’ section in Galliano’s Wikipedia page for highlights). Wintour is also the creative director of Conde Nast publications. A glowing review of The First Monday in May in Conde Nast publication Vanity Fair commends the film’s “audacious” choice to feature Galliano, describing him, passively, as a lightning rod for controversy. Wintour didn’t direct The First Monday in May, of course, but the evidence points to her strong influence on the creative decisions around the depiction of Galliano.

I wouldn’t want to get in an argument about whether Galliano’s anti-semitic rants are more or less unacceptable than Gibson’s, or whether one is more honestly rehabilitated than the other. On the former point both are pretty terrible, and on the latter one can ultimately only conjecture. But I can respond to the ways in which their films act as vehicles to service their personal narratives of forgiveness, and with Gibson, I just don’t see it. Blood Father can’t be meaningfully read as an attempt to rehabilitate his public image; nor, I suspect, can Hacksaw Ridge. That’s not their function.

For this reason I cringe when I think of the hidden yet cunningly crafted agenda of The First Monday in May, or when I read carefully placed and managed interviews with The Birth of a Nation’s Nate Parker, asking for forgiveness for something long in the past (while promoting a film about historical wrongs from a previous century), or when I consider Mike Tyson turning his assault on Evander Holyfield into a punchline for fun and profit. Forgiveness under duress – and make no mistake, there’s a reason that they call it a PR offensive – is no forgiveness at all, and to manipulate an audience into forgiveness, while strategic and possibly effective, feels filthy.

If we feel that those who do wrong need to be able to forgiven and re-integrated into society – and I feel that they do – I desperately want there to be a mechanism for forgiveness. And yet deciding when to forgive is up to every individual. So there will be no calculus, just an endless parasocial negotiation on each case. Meanwhile, Gibson’s off to his next acting role. He’ll be appearing in the adaptation of The Professor and The Madman, the true story of the unlikely collaboration that brought about the Oxford English Dictionary. His co-star? Sean Penn.