On Being an Art Anakema

Multidisciplinary artist and curator Leafa Wilson & Olga Krause on a lifelong performance and being destined for obscurity.

We’re collaborating with Creative New Zealand to bring you the groundbreaking Pacific Arts Legacy Project. Curated by Lana Lopesi as project Editor-in-Chief, it’s a foundational history of Pacific arts in Aotearoa as told from the perspective of the artists who were there.

Don’t even look for me. Seriously. Here’s where you will not find me: Pasifika art books; New Zealand art history books; in the mouths of curators of art. I am not in the schools of maliē (sharks) in Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa – the Pacific Ocean. I am with the kōura (freshwater crayfish, crawlies) found at the perimeter of Lake Te Moananui in South Waikato on the land of Ngaati Raukawa. In Sāmoan terms, I am an art anakema (misfit, anathema) and know I am: I am at peace with this now. I was destined for obscurity. That’s my intro to myself.

Sale (arrived on the TSMV Tofua in 1959) and Etevise (arrived on the TSMV Matua in 1961) got married in Taamaki Makaurau in 1961, after picking up their relationship that began in Taufusi and Vaimoso – neighbouring townie villages on Upolu, Sāmoa. They settled in Tokoroa because Ma had two of her remaining siblings living there. Kinleith pulp and paper mill brought many Sāmoans and Cook Islanders to the town. We were just one family of hundreds. My parents went on to have eight children, of which I am number four.

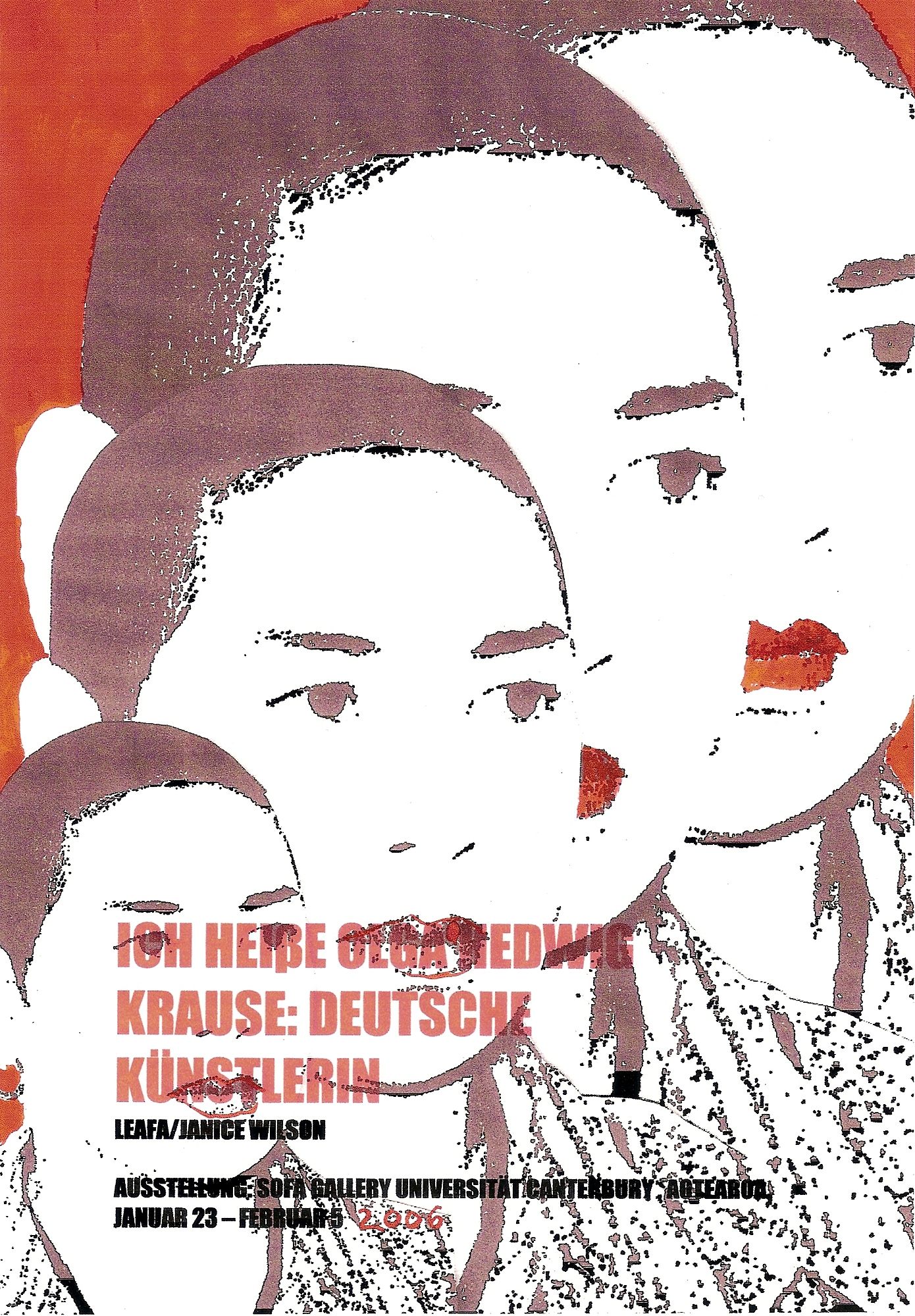

The Sāmoan word for cyclone is afā

On same day as my birth in the South Waikato on 26 January 1966, a tropical cyclone was busy thrashing my parents’ home of Sāmoa. My maternal gramps – Nikolao Tupuola – was still living back home in Sāmoa at that time and was there during that afā. It was he who named me after that specific weather event: Taufau Leafā (le afā). He, my ma, Sāmoan-German pa and Uncle Lio are to blame for the list of names I answer to. Olga Hedwig Janice Krause is the name I was given at birth. Leafa doesn’t appear on my birth certificate because it is a bestowed name. It is names that form one of the deepest areas of interest for me as an inquisitor of my own cultural and social formation. The names Olga Hedwig Krause are a kind of lifelong performance because they do not belie any of who I am and how I appear in this world as a person and as an artist. It is more likely that you might find me somewhere using that name on a Google search than by my other names.

Ich heiβe Olga Hedwig Krause: Deutsche Künstlerin, 2005, inkjet poster print.

It is my lifelong durational performance art work. It is strategy. It is a working professional name. It is a name by which I have survived as a person of colour in the Western whiteness that makes up the majority of art institutions in Aotearoa. It is always shocking to people who know me when they find out the true rationale for my use of my names. A particularly polarising online art writer and critic stated that my using my birth certificate name was bullshit that I needed to cut out (you’ll have to look that reference up yourself), which was not fun at the time.

Yet equally not fun, or perhaps even more wounding for me, people within the Pasifika art scene seemed not to acknowledge me or didn’t know what to do with me without a visually ‘Pacific’ handle. In 1999, I made a photographic series documenting staged scenes that pitted white male professionals against a fully adorned taupou (revered high-ranking village virgin in old Sāmoan tradition). The series was called Ua Tutusa Tau‘au (We are of equal standing). The series showed at Archill Gallery, which was co-owned and under the directorship of the late Ngaai Tuuhoe gallerist Terry Firkin, alongside the legendary and late Jim Vivieaere. My sister Karen Muamua, and local Hamilton Sāmoan women Maria Mase and Sr. Koreti Savai‘inaea posed as taupou. Each stood with a nifo oti (ceremonial knife), alongside a police constable, the actual Catholic Bishop of Hamilton at the time, an actual lung specialist at the hospital and a well-known Hamilton artist. These were rejected by curators for a show of Pasifika art at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom in 2006. This, too, made me realise that my work is very much misunderstood. I am creating my own distance, perhaps.

Taupou and Constable, Desert Road, Tuuwharetoa, 1999, Cibachrome print.

I went to art school in Ootepoti Dunedin from 1984 to 1986. I felt like I really understood the properties of diffusion: I went from living in a high concentration of brown people to a low concentration in the netherworlds of Te Ika a Maaui. I think the depth of the effect on me cannot be understated.

I began my painting research in that first year at art school with researching the tatau motifs belonging to the material cultural practice of Sāmoa. Probably the only tattooing I had ever seen was that of my Uncle Lio, who lived with us on and off. His pe‘a made me really think about the art form and whether I, as a diaspora kid, had any rights to the reification of these marks. I started researching these through the notes of Te Rangi Hiroa’s research, Samoan Material Culture.I began to fully comprehend that these aren’t just any old marks. I began to explore them as part of my visual language in painting. I probably investigated these marks for at least the three years I was at art school. I came to my own conclusion that for me to continue to ‘use’ these for my own purposes was exploitative. It was at this juncture that I truly decided that I would veer as far away as I could from further exploitation of my own sacred cultural traditional marks. Marks I now bear on my thighs in the form of the malu. Those more literal works of mine, of the early to mid-1980s, are more like journal notes about how I wished these tatau markings were not external but internal – emblazoned in my mind and able to be borne out of my tongue through the spoken Sāmoan language and through my hips and limbs, as fluid narrators of our danced history. But none of this was part of the path set out for me by my ancestors So‘oae‘malelagi and Matai‘a Fuli, my maternal grandmothers.

I see the entirety of my art practice is like one perpetual search to locate the purest form or most essential expression of what lies within.

My practice has always been seeking mystery, and moving toward abstraction, the intangible. That which cannot be seen, held or owned. For me, my legacy of performance art can only ever be viewed in someone else’s images of me. That actual work is gone. My paintings are owned by people I know well, not by galleries.

So, in reality, all I have to offer a coming generation is the energy I have put into curating exhibitions that have shifted the art world a little closer to the Moana and the Awa, and an art practice that doesn’t need to be seen, documented or kept, but rather is felt and recalled in strange moments that the ancestors intended to be experienced.

*

This piece is published in collaboration with Creative New Zealand as part of the Pacific Arts Legacy Project, an initiative under Creative New Zealand’s Pacific Arts Strategy. Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief of the project.

Series design by Shaun Naufahu, Alt group.

Header photo by Edith Amituanai.